You may find here the Working paper in pdf.

Executive Summary

It was around the mid-2000s when Turkey—if only for a short period of time—promulgated the idea of “zero problems with neighbours”. At the time, Turkey was seeking positive reforms in all aspects of public life and a cooperative future with neighbouring countries based on mutual understanding and converging interests. Furthermore, Turkey imagined itself as a bridge between, not as a wall separating and isolating, different regions.

Unfortunately, those days are long gone. For almost a decade now, Turkey has been reactionary in its treatment of its own citizens and solipsistic with regard to its neighbours. Democratic backsliding and human rights abuses inside Turkey have become the norm, while militarisation and unilateralism increasingly characterise its foreign policy choices. Its government actions have begun to resemble those of a rogue state.

This report seeks neither to explain the intricacies of Erdoğan’s problematic behaviour towards its own people and the rest of the world, nor to denigrate Turkey’s standing. Rather, it aims to raise the alarm about the slippery slope Turkey finds itself on, hopefully well before his governance causes irreparable damage to the region.

The report starts by presenting general aspects of Turkey’s relationship with international stakeholders, such as the EU and the US. It proceeds by mapping out internal developments that exemplify strong tendencies of democratic backsliding and human rights abuses. The third part focuses on regional aspects of Turkey’s foreign policy behaviour, starting with the most severe cases that epitomize the militarisation of its foreign policy and violations of international law. It concludes with various cases of political differences between Turkey and states on its periphery, which, combined with the other more severe cases described, demonstrate how Turkey’s foreign policy expectations of ‘zero problems with neighbours’ have turned into a ‘zero neighbours’ reality.

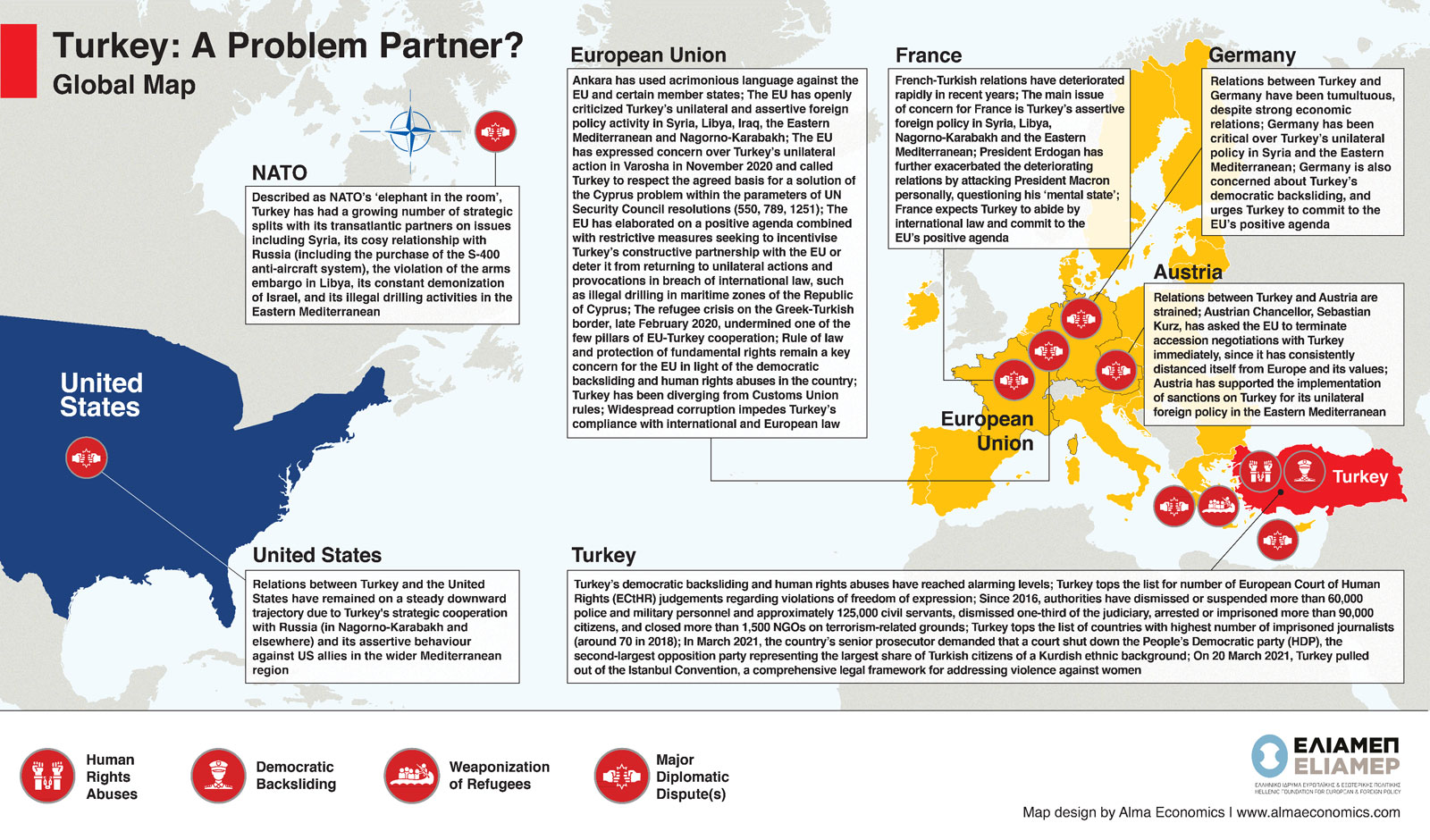

Map 1: Turkey: A Problem Partner? Global Map

Map 2: Turkey: A Problem Partner? Regional Map

I. Global Perspectives

1. EU-Turkey Relations on Diverging Paths

When dealing with Turkey in recent years, the EU institutions and EU Member States have often oscillated between countering Ankara’s animosity and signaling openness to dialogue. Turkey’s democratic backsliding and its poor record in human rights, as well as the recent developments in the Eastern Mediterranean, Syria, Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh, have demonstrated a growing gap between European values and norms, on the one hand, and Turkey’s policy choices, on the other.

Specifically, after the attempted military coup in Istanbul and Ankara and the ensuing purge, the EU institutions criticized Erdoğan for the “disproportionate severity” of his response, which transcended the mere containment of the crisis in magnitude and turned to a new and darker page for the country’s democracy, rule of law and human rights (European Parliament, 2018, p. 1). The strong language used by the EU to criticize developments in Turkey highlights the fact that “Turkey has increasingly and rapidly distanced itself from the EU’s values and its normative framework”, thus bringing “EU-Turkey relations to a historical low point” (European Parliament [Committee on Foreign Affairs], 2020, p. 4).

Particularly, three high-profile cases of judicial misconduct have provoked the EU to strongly condemn Turkey’s poor human rights record and its increasing democratic backsliding. The first is the case of Selahattin Demirtaş, the former co-leader of the People’s Democratic Party, the second-largest opposition party in the country which represents the largest share of Turkish citizens with a Kurdish ethnic background, who has been detained since 2016 for allegedly supporting the PKK’s agenda. The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) ruled that his detention “had pursued the ulterior purpose of stifling pluralism and limiting freedom of political debate” and that these concepts are “at the very core of the concept of a democratic society” (Pitel, 2020a). The second case is that of the prominent Turkish businessman and civil society activist, Osman Kavala, who was arrested in 2017 on the charge of “seeking to violently overthrow the government” (Pitel, 2019). In December 2019, the ECtHR ruled “that his detention took place in the absence of sufficient evidence that he had committed an offence, in violation of his right to liberty and security under the European Convention on Human Rights. The ECtHR also found that Mr Kavala’s arrest and pre-trial detention pursued an ulterior purpose, namely to silence him and dissuade other human rights defenders” (Council of Europe, 2020).

In both cases, the EU has made it clear that respect for fundamental rights forms the basis of EU-Turkish relations. In her address to the European Parliament on behalf of the EU High Representative, Helena Dalli, the Commissioner for Equality, stated that “As a candidate country and long-standing member of the Council of Europe, Turkey urgently needs to make concrete and sustained progress in the respect of fundamental rights, which are a cornerstone of EU-Turkey relations. Progress in the cases of Demirtaş, Kavala and other human rights cases is of the essence” (Dalli, 2021). In addition, the Commissioner highlighted that “Decisions and actions taken by the Turkish authorities against mayors from opposition parties remain deeply concerning.[1] Hundreds of local politicians, elected office holders and thousands of members of the Peoples’ Democratic Party [HDP] have been detained on terrorism-related charges since the local elections in March 2019. Investigations were launched against others” (ibid.). Furthermore, she warned that: “Some even consider banning the HDP, which would clearly send a further very worrying signal” (ibid.).

The third case is precisely what Commissioner Dalli warned against, namely the banning of the HDP, the third largest party in Turkey representing the largest share of Turkish citizens with a Kurdish ethnic background.[2] In a dramatic turn of events, on 17 March 2021 the Supreme Court Prosecutor, Bekir Sahin, demanded the closure of HDP due to the HDP allegedly “acting together with PKK terrorists and affiliated organisations, acting as an extension of such organisations” (Al Jazeera, 2021). The EU reacted swiftly, strongly condemning this extremely worrying development.

“European Union institutions have expressed their deep concern about the decision to strip Ömer Faruk Gergerlioğlu, a Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) representative in the Turkish Grand National Assembly, of his parliamentary seat and parliamentary immunity and about his imminent incarceration, as well as the lawsuit initiated by the prosecutor of the Court of Cassation requesting the closure of the HDP.

Closing the second largest opposition party would violate the rights of millions of voters in Turkey. It adds to the EU’s concerns regarding backsliding with regard to fundamental rights in Turkey and undermines the credibility of the Turkish authorities’ stated commitment to reforms.

As an EU candidate country and a member of the Council of Europe, Turkey urgently needs to respect its core democratic obligations, including respect for democracy, human rights and the rule of law”

(Borrell & Várhelyi, 2021)

In addition, the EU is deeply troubled by Turkey’s “lack of commitment to carrying out the reforms assumed in the accession process” (European Parliament [Committee on Foreign Affairs], 2020, p. 4). The European Parliament has summarized the lack of progress with regard to Turkey’s convergence (“now transformed into a full withdrawal”) thus: “Stark regression in three main areas: backsliding on the rule of law and fundamental rights, adopting regressive institutional reforms and pursuing a confrontational foreign policy”. The EP is “further concerned” by the fact that this regression has increasingly been accompanied by “an explicit anti-EU narrative (ibid.). The High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy (HR/VP), Josep Borell, in his recent report to the European Council stipulated that

“Turkey’s increasingly assertive foreign policy collided with EU priorities under the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). While the institutional framework enabling Turkey’s participation in CFSP and the Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) is in place, in 2020 Turkey recorded a very low alignment rate of around 11%. Turkey continued not to align with most Council decisions (restrictive measures), including related to Russia, Venezuela, Syria and Libya, and with EU declarations such as on Nagorno-Karabakh.”

(European Commission [High Representative of the EU for Foreign and Security Affairs], 2021, p. 4)

The “confrontational foreign policy” and the “very low alignment rate” are showcased in the Turkish intervention in Syria. It has been reported that “Turkey’s military has worked diligently to develop the combat capacity of its Syrian proxies, deploying them alongside Turkish regular forces in multiple incursions against Kurdish militants in northern Syria”. The UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights claims that Turkish-backed Syrian mercenaries were “former militants who fought for the likes of Islamic State and al-Qaida-affiliated militant groups” (Deutsche Welle, 2020b).

The EU “condemned” Turkey’s “unilateral military action in north-east Syria” and urged Turkey to “end its military action, withdraw its forces and respect international humanitarian law” (European Commission, 2020, p. 6). That the EU called on Turkey to respect international humanitarian law underlines the fact that the Turkish intervention is on a divergent path from international law and EU norms and values. In fact, the vast majority of Member States decided to “halt arms export licensing to Turkey”, which further entrenched in practice the divergence in the foreign policy of the two blocs (ibid., p. 8).

Another controversial front in the relationship between Turkey and the EU concerns the Nagorno Karabakh conflict. The European Parliament has noted that over the past 15 years, Turkey has “tried to increase its influence on the geopolitical orientation of central Asia and Azerbaijan, with which it has strong cultural links” (European Parliament, 2018, p. 4).

Indeed, the European Parliament “regrets” that Turkey, instead of calling for an end to the violence and for peaceful negotiations in support of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) Minsk Group, has “decided to unconditionally sustain the military actions of one of the sides in the recent conflict in Nagorno Karabakh” (European Parliament [Committee on Foreign Affairs], 2020, p. 7). In addition, the High Representative of the European Union, Josep Borrell, has made it clear that the EU’s “framework… to mediate and to act on this conflict is the OSCE Minsk Group” (Wesel, 2020) and that “Turkey’s most recent support for military actions in the Caucasus during the Nagorno Karabakh related hostilities have led to further questioning of Turkey’s regional role. It departed from promoting a peaceful settlement and supported Azerbaijan’s push for a military solution.” (European Commission [High Representative of the EU for Foreign and Security Affairs], 2021, p. 5).

In fact, “Turkey’s indigenously produced drones, coupled with Turkish training and tactics, significantly bolstered Azerbaijan’s ability to inflict damage on Armenian forces. Turkey also transported hundreds of Syrian rebel fighters to the front lines to fight for Azerbaijan” (Danforth, 2020).

In particular, the recruitment of Syrian rebel fighters for the Nagorno Karabakh conflict generated international outrage and for good reason, as it potentially violates the International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing and Training of Mercenaries. Turkey is not a signatory to that Convention, but “both Libya and Azerbaijan, which have received Syrian mercenaries on their territory, have ratified it” (Morgan, 2020).

This show of force on the part of Turkey is not an isolated instance. Rather, it is part of a broader shift in the foreign policy of Turkey, which has been employing hard power to alter regional dynamics to further its own interests. In this spirit, “Ankara has emphasized its willingness to act independently of, or even in direct opposition to, its former Western allies while building a relationship with Russia that is simultaneously cooperative and competitive” (Danforth, 2020).

German Green party politician Cem Özdemir summarised this divergence from the EU stance as “Turkish support for Azerbaijan’s warmongering” (Deutsche Welle, 2020a). Peter van Dalen, a Dutch Christian Democrat MEP, said that Turkish President Erdoğan was trying to “recreate the Ottoman Empire”, while the Bulgarian MEP Angel Dzhambazki accused Turkey of nurturing “imperial fantasies” (Wesel, 2020).

But Nagorno Karabakh and Syria are not the only fronts on which Turkey has demonstrated divergence from such EU norms and principles as respect for international law, dialogue and good neighbourly relations; it is perhaps the Eastern Mediterranean that epitomised the dissonance between Turkey’s stance and the EU approach. Greece and Cyprus continue to report “repeated and increased violations and an increasing militarisation of their territorial waters and airspace by Turkey.” (European Commission, 2020, p. 65).

In addition, “Flights over Greek inhabited areas increased significantly, in violation of international law…Overflights of Greek mainland in the Evros river border region were also reported” (ibid., p. 66).

In the 2020 report, the European Commission highlighted that “Turkey’s foreign policy increasingly collided with the EU priorities under the Common Foreign and Security Policy”, and that “Dialogue with the EU was hampered by Turkey’s provocative actions in the Eastern Mediterranean” (ibid., p. 106). The Commission stresses that in the Eastern Mediterranean: “The EU will support peaceful dialogue based on international law, including through a multilateral conference that could address issues on which multilateral solutions are needed”, implicitly suggesting that Turkey is not aligned with the EU’s path of respecting international law and endorsing multilateralism (2021, p. 14).

Tensions in the Aegean Sea and the Eastern Mediterranean is becoming a chronic issue in EU-Turkey relations. In March 2018, the European Council “strongly condemned Turkey’s continued illegal actions in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean Sea and recalled Turkey’s obligation to respect international law and good neighbourly relations and to normalise relations with all EU Member States” (European Commission, 2018b, p. 6). The European Council also expressed its “grave concern” over the continued detention of EU citizens in Turkey, including two Greek soldiers, and called for the swift and positive resolution of these issues in a dialogue with Member States” (ibid.).

Once again, in March 2019, the EU called on Turkey to “refrain from any illegal acts, to which it would respond appropriately and in full solidarity with Cyprus” (European Commission, 2019, p. 7). The EU has also stressed the need to “respect the sovereignty of Member States over their territorial sea and airspace” (ibid., p. 60). This was in the context of Turkey’s “continued challenging” of the right of the Republic of Cyprus to exploit hydrocarbon resources in the Cyprus Exclusive Economic Zone. In February 2018, Turkish naval vessels repeatedly undertook manoeuvres to block the drilling operations of a vessel contracted by an Italian company and commissioned by Cyprus, resulting in the planned drilling activities being aborted (ibid.). In May 2019, Turkey sent a drilling platform accompanied by military vessels into the Republic of Cyprus’ Exclusive Economic Zone, escalating tensions further. The EU called on Turkey to “respect the sovereign rights of Cyprus” to explore and exploit its natural resources in accordance with the EU acquis and international law, including the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (ibid., p. 7).

In the light of “the unauthorised drilling activities of Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean”, the Council decided in July 2019 to suspend negotiations with Turkey on the Comprehensive Air Transport Agreement, not to hold the EU-Turkey Association Council for the time being along with further meetings in the EU-Turkey high-level dialogues, to endorse the Commission’s proposal to reduce pre-accession assistance to Turkey for 2020, and to invite the European Investment Bank to review its lending activities in Turkey, notably with regard to sovereign-backed lending. The European Council also stressed that: “In case of renewed unilateral actions or provocations in breach of international law, the EU will use all the instruments and the options at its disposal in order to defend its interests and those of its Member States” (European Commission, 2020, p. 8). On 10-11 December 2020, the European Council noted that “Regrettably, Turkey has engaged in unilateral actions and provocations and escalated its rhetoric against the EU, EU Member States and European leaders. Turkish unilateral and provocative activities in the Eastern Mediterranean are still taking place, including in Cyprus’ Exclusive Economic Zone.” (European Council, 2020a, p. 11).

And since Greece’s borders with Turkey are also European borders, Turkey’s attempt to create waves of refugees or migrants at the Greek-Turkish border constitutes another episode in the deterioration of EU-Turkish relations. In March 2020, “Turkey actively encouraged migrants and refugees to take the land route to Europe through Greece” (European Commission, 2020, p. 7). On February 28, Erdoğan proclaimed Turkey’s border with Europe “open”, and his country’s authorities were told not to hinder any refugees attempting to cross into the EU. Within 48 hours, nearly 13,000 refugees had arrived at the Greek-Turkish border, while hundreds more had landed on Greek islands. At the same time, the Turkish police deployed to prevent any refugees from returning to Turkey. This situation forced Greece to deploy its military and request additional assistance from Frontex, the EU’s border police. The Turkish government has even gone as far as engaging in a disinformation campaign against the Greek government, falsely stating that Greece is murdering refugees and comparing the border situation to Auschwitz (Gadalla, 2020). The Commission “strongly rejected” Turkey’s use of “migratory pressure for political purposes” (European Commission, 2020, p. 7); this weaponization of migrants, to the extent that some commentators have described the phenomenon as a “hybrid war” (Gerodimos, 2020), lies in stark opposition to the European ideal of respect for human rights.

Even before the refugee crisis at the Greek-Turkish border in March 2020, the EU leadership had warned Turkey not to attempt to blackmail the EU. Specifically, on 11 October 2019, the President of the European Council, Donald Tusk, “sharply criticized Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s threat to “open the gates” and “send 3.6 million refugees your way” if the EU labels Turkey’s incursion into Syria as an “invasion”” with the potential to lead to a “humanitarian catastrophe” (Deutsche Welle, 2019a). He stated that “Turkey must understand that our main concern is that their actions may lead to another humanitarian catastrophe, which would be unacceptable. Nor will we ever accept that refugees are weaponised and used to blackmail us. That is why I consider yesterday’s threats made by President Erdoğan totally out of place” (Strupczewski, 2019).

Furthermore, European leaders have expressed concerns about Turkey’s expanding influence in the Western Balkans. Speaking to the European Parliament, French President Emmanuel Macron put Ankara and Moscow in the same category, saying he did not want “a Balkans that turns towards Turkey or Russia.” (Radosavljevic & Morgan, 2018). The danger is that Turkey’s backsliding may also influence the shaping of the political culture of the Western Balkans. In fact, this was evident from the Commission’s reporting of Turkish authorities continuing to put “pressure on authorities in the Western Balkans to locally prosecute and extradite alleged members of the Gülen movement” (2020, p. 66). Asli Aydintasbas observed that: “Turkey chose the Balkans as a battleground in the fight against the Gülen movement” (Hopkins & Pitel, 2021). Six renditions of alleged Gülenists have taken place in Kosovo and one in Albania. The UN Human Rights Council stated that the Kosovo Intelligence Agency had “effectively kidnapped” the six men and referred the case to a special UN rapporteur for further investigation (ibid.).

Turkey’s bilateral relations with core EU countries such as Germany and France, as well as other important Member States such as Austria, has been another crucial factor in the deterioration of EU-Turkey relations. For instance, the deterioration in these bilateral relations has ruled out positive steps towards a ‘constructive agenda’ on both sides. On the one hand, the EU is refusing to open negotiations on the modernisation of the Customs Union and on visa liberalisation, while Turkey is refusing to ratify the Paris Climate Agreement, which it has already signed. It is indicative that Turkish President Erdoğan justified Turkey’s refusal to ratify the agreement on the grounds that “France and Germany had promised to work to include Turkey among developing countries but they never kept their pledge” (Demirtaş, 2020).

Despite Turkey’s close economic ties with Germany (Yaşar, 2020, pp. 7-21), relations have seen moments of significant deterioration, mainly due to Turkey’s democratic backsliding, its poor implementation of the rule of law, and its substandard record on human rights as well as its unilateral actions in Syria and the Eastern Mediterranean. Accordingly, Germany has been pushing the EU not to send a “wrong signal” to Turkey by opening negotiations for the modernisation of the Customs Union (CU), and has argued that Turkey’s pre-accession aid (IPA) should be conditional on Turkey’s efforts to support democracy and the rule of law. Hence, Germany asked the Commission to “shift funding away from Turkey in a way that is meaningful compared to the overall funding Turkey receives under the IPA schemes” (Heller, 2017; Tastan, 2017). The EU common denominator was reflected in the European Council’s decision in June 2018, namely that “The Council notes that Turkey has been moving further away from the European Union. Turkey’s accession negotiations have therefore effectively come to a standstill and no further chapters can be considered for opening or closing and no further work towards the modernisation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union is foreseen.” (European Council, 2018, p. 13).

Conditional opening of the negotiations for the modernisation of the CU is now the EU position. In the most recent European Council, the EU reiterated that

“Provided that the current de-escalation is sustained and that Turkey engages constructively, and subject to the established conditionalities set out in previous European Council conclusions, in order to further strengthen the recent more positive dynamic, the European Union is ready to engage with Turkey in a phased, proportionate and reversible manner to enhance cooperation in a number of areas of common interest and take further decisions at the European Council meeting in June: on economic cooperation, we invite the Commission to intensify talks with Turkey to address current difficulties in the implementation of the Customs Union, ensuring its effective application to all Member States, and invite in parallel the Council to work on a mandate for the modernisation of the Customs Union. Such a mandate may be adopted by the Council subject to additional guidance by the European Council…”

(European Council, 2021, p. 11)

Even major private investments like Volkswagen’s, as well as smaller ones, have been affected by Turkey’s domestic and regional policy choices (Süddeutsche Zeitung, 2021).

Franco-Turkish relations have also deteriorated rapidly in recent years. The main issue of concern for France is Turkey’s assertive unilateral foreign policy in Syria, Libya, Nagorno-Karabakh and the Eastern Mediterranean. President Macron has argued that Ankara is acting in a “warlike” manner; he has also commented on the specifics of the Nagorno-Karabakh case, stating that: “We now have information which indicates that Syrian fighters from jihadist groups have [transited] through Gaziantep [in Southeastern Turkey] to reach the Nagorno-Karabakh theatre of operations” (Irish and Rose, 2020). President Erdoğan has further exacerbated the deteriorating relations by attacking President Macron personally, accusing him of Islamophobia, questioning his ‘mental health’, and publicly calling on Turkish citizens to boycott French products against the letter and the spirit of the Customs Union (Al Jazeera, 2020a).

Finally, Austria’s Chancellor, Sebastian Kurz, has in recent years been openly promoting the cessation of Turkey’s EU membership negotiations in the light of its rejection of EU ideals and norms. In response to a question about the future of EU-Turkey relationship, he said: “EU membership negotiations with Turkey should be stopped immediately; Turkey has consistently moved away from Europe and its values over the last few years. At the same time, we should concentrate on exploring other forms of collaboration between the EU and Turkey as neighbours” (Nedos, 2018). The Austrian Chancellor has expressed in no uncertain terms his condemnation of Turkey’s unilateral actions in the Eastern Mediterranean, and of Erdoğan’s announcement in March 2020 that Turkey would not be implementing the 2016 Statement, a framework that tries to address the migration crisis. Kurz stated that: “If we give in to Erdoğan and Turkey, then good night, Europe[…]”, and also that “Europe must not allow itself to be blackmailed by Erdoğan” (E-kathimerini, 2020).

To summarise, the EU stands firm in its belief that “all differences must be resolved through peaceful dialogue and in accordance with international law” (European Commission, 2020, p. 64). Turkey has repeatedly challenged this cornerstone of European cooperation, be it in the domestic sphere with its severe democratic backsliding and grave human rights violations, or via its assertive foreign policy vis-à-vis Libya, Nagorno Karabakh, Syria and the Eastern Mediterranean. To make matters worse, Turkey’s relationship with a number of EU Member States including France, Austria, Germany, Greece and Cyprus is, to say the least, dysfunctional.

2. Turkey drifting away from the West (US and NATO)

Relations between Turkey and the United States have remained on a steady downward trajectory since the beginning of the 2010s. The main reasons behind this downward path relate to Turkey’s strategic cooperation with Russia and Turkey’s assertive behaviour against US allies in the wider Mediterranean region. Especially after the failed military coup against President Erdoğan in July 2016, it became clear to the US and NATO—as well as to most of Turkey’s neighbours— that Turkey’s assertive and frequently illegal behaviour, if left unchecked, would entail certain negative repercussions for the stability of the broader MENA region, the interests of the United States, and the coherence of the Atlantic Alliance.

The retreat of US strategic attention from the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East—which goes back to the “Asia pivot” under the Obama administration—was viewed by Turkey’s President Erdoğan as a window of opportunity, prompting him to seek to fill the “power vacuum”. To this end, Erdoğan was not hesitant in deploying hard-power means and tactics aimed at achieving short-term gains.

Under Erdoğan, Turkey has intervened militarily in Syria, Iraq, Libya, and the Caucasus while establishing military bases in Qatar and Somalia and seeking to expand its influence in the Red Sea. Turkey has also developed its domestic defence production, including armed drones which were used to devastating effect in the recent fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh, where Turkey helped its close ally Azerbaijan take back disputed territory lost decades earlier to their mutual rival Armenia. Turkey has also made significant new maritime claims to disputed waters in the Eastern Mediterranean, leading to severe tensions with Greece, Cyprus and France. President Erdoğan considered these actions essential steps towards Turkey regaining what he deems its rightful place as a dominant regional player and a ‘central power’ in world politics (Hoffman, 2021).

More or less as a consequence of the unilateral and assertive policies, Turkey has had a growing number of strategic splits over the last decade with its transatlantic partner, the United States, on a plethora of issues including Syria, Turkey’s cosy relationship with Russia (including the purchase of the S-400 anti-aircraft system), the violation of the arms embargo in Libya, Turkey’s constant demonization of Israel, and its aggressive drilling in the Eastern Mediterranean. It would seem that Turkey’s aggressive pursuit of regional goals under President Erdoğan, his warm relationship with Russian President Vladimir Putin and their coordinated actions in certain areas, hang over all the aforementioned issues. Moreover, taken together, Turkey’s military operations in Syria, Libya and Iraq, the Blue Homeland doctrine, and the war-like narratives –to name but a few– have largely redefined Turkey as a problematic ally of the West.

Turkey’s aggressive attempts to redraw the regional order were therefore considered to be irresponsible and at the expense of US interests[3], while a NATO ally’s cosy relationship with Russia’s President Putin was unacceptable to the U.S. It seemed that Turkey wanted to have “the best of both worlds”, enjoying the benefits of NATO membership while avoiding the core responsibility of presenting a united front towards Russia.

It is these realities that have led many in the US government to question whether Turkey remains a fully committed ally.

Described by the New York Times as NATO’s “elephant in the room” (Erlanger, 2020), Turkey sees the “equidistance policy” it pursues vis-à-vis US/NATO and Russia as a means of procuring missile defence systems from Russia (for political, not technical reasons) amidst a NATO-anchored military infrastructure which includes bases in Incirlik, Kürecik, and Konya and a land forces command in Izmir. Interestingly, at a lower level, Turkey is involved in NATO’s “Sea Guardian” operation to prevent arms deliveries to all parties in the Libyan conflict, while it continues to block inspection procedures by Greek, Italian and French navies operating as part of the same NATO operation when they attempt to inspect civilian vessels delivering Turkish armaments to the Tripoli government Turkey’s policy is perceived in Western Europe as an à la carte approach to NATO participation, which depends on its national interests of the moment (Pierini, 2020, pp. 7–8).

In particular, Turkey’s purchase of the S-400 air defence system from Russia led to the Trump administration’s decision to remove Turkey from the F-35 programme, America’s most expensive weapons platform, as the S-400 is said to pose a risk to the NATO alliance as well as Lockheed Martin’s F-35 stealth fighter (Macias, 2019). Moreover, the possibility that Turkey will fully activate the purchased S-400 air defence system, or pursue deeper cooperation with Russia in response to sanctions imposed on Turkey by the US on 14 December 2020 under the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA)[4], continues to seriously undermine the US-Turkey relationship (Macias, 2020). It is also worth noting that the separate threat of sanctions against Turkey’s state-owned Halkbank for avoiding Iran sanctions is already hanging over the already-weakened Turkish economy.

Unsurprisingly, both the bipartisan letter sent to President Joe Biden by 54 Senators[5], and the letter sent to the Secretary of State Anthony Blinken by a bipartisan group of more than 180 members of the American Congress[6], hold Turkish President Erdoğan accountable for human rights abuses, for marginalizing domestic opposition, for Turkey’s democratic backsliding, and for straining relations between the two nations, while pointing out the importance of changing Erdoğan’s behaviour in the field of human rights in the context of further developing and expanding US-Turkish relations.

II. Domestic Perspectives

3. A Democracy in Crisis

The symptoms of Turkey’s democratic backsliding are widespread in every sphere of political, economic and social life. What started as a government strategy to mitigate and manage the crisis of the failed military coup has turned out to be a full-scale reversal of Turkey’s democratization and liberalization process.

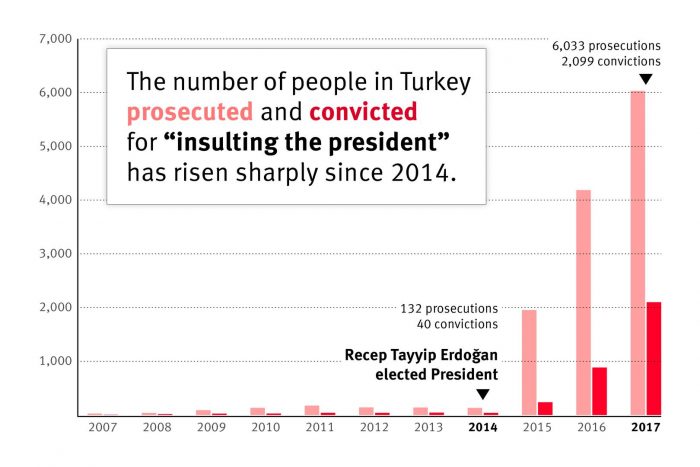

It is indicative that “Since the 2016 coup attempt, authorities have dismissed or suspended more than 60,000 police and military personnel and approximately 125,000 civil servants, dismissed one-third of the judiciary, arrested or imprisoned more than 90,000 citizens, and closed more than 1,500 nongovernmental organizations on terrorism-related grounds…” (U.S. State Department, 2021, p.1; also Kucukgocmen, 2020)) and at least a hundred media establishments were closed without judicial proceedings (Council of Europe, 2016, p. 2); (Turkey tops the list of countries with the highest number of imprisoned journalists (around 70 in 2018) (The Economist, 2019); Prosecutions under article 299 of the Turkish penal code for “insulting the president” have risen dramatically from 132 in 2014 to over 6,000 in 2017 (Human Rights Watch, 2018).

The institutional framework has been severely compromised, including such core values of democracy as the rule of law, checks and balances, and the separation of powers. A hegemonic presidency is currently in place, preventing scrutiny and accountability.

And even in those rare instances where the institutional framework has not been corroded, its continued weak implementation, the lack of coordination between institutions, and the lack of awareness of and commitment to law enforcement, due largely to bias and clientelism, lead to grave violations of human rights and severe discrimination against minorities.

Violations of democratic values, fundamental rights and the rule of law paint a bleak picture of Turkey today. Despite the lifting of the state of emergency in July 2018, the adverse impact of two years of emergency rule continued to undermine democracy and fundamental rights. More recently, a new cycle of controversy in relation to Turkey’s democratic backsliding has begun: on 17 March 2021, in a dramatic development, “The country’s senior prosecutor […] demanded a court shut down the People’s Democratic party (HDP), whose base is largely Kurdish, accusing it of links with armed militants and activities that undermine national unity, according to a copy of the 609-page indictment” (Yackley, 2021b). This constitutes a major negative development for the future of democracy in Turkey, given that the HDP is the second-largest opposition party in the country and represents politically the largest share of Turkish citizens with a Kurdish ethnic background.

Back in 2018, the European Commission demonstrated a clear understanding of the country’s political upheaval, declaring its “immediate” and “strong” condemnation of the attempted coup and reiterating “its full support to the country’s democratic institutions and recognizing Turkey’s legitimate need to take swift and proportionate action in the face of such a serious threat” (2018b, p.3). Having done so, it immediately warned against “the broad scale and collective nature, and the disproportionality of measures”, stating that “Turkey should lift the state of emergency without delay” (ibid.). Turkish violations of international and European law were still found to be problematic in the report: for example, “emergency decrees have notably curtailed certain civil and political rights, including freedom of expression, freedom of assembly and procedural rights” (ibid.).

Nevertheless, the Commission’s “concerns” had escalated by the time this report was published into condemnation of Turkish practices, with reference to “worrying [rule of law] developments” (2018a, p. 10). In particular the European Commission notes that: “Certain legal provisions granting extraordinary powers to the government authorities and retaining several restrictive elements of the emergency rule have been integrated into law” (2020, p.4). It is highlighted that “as a candidate country [for EU accession], Turkey needs to provide stability for institutions which guarantee democracy” (European Commission, 2018a, p. 10), suggesting that the current institutional framework is sub-par and lacks the enforcement of the requisite checks and balances.

In a similar vein, the Commission’s point that “Turkey needs to build up the necessary administrative capacity to ensure EU legislation is properly implemented” (ibid., p. 12) indicates that there is a legitimacy problem in Turkey’s institutional set-up which needs to be addressed if the country is to reach the European threshold. Indeed, “the Constitutional amendments endorsed by referendum on 16 April 2017 were assessed by the Venice Commission of the Council of Europe as endangering the separation of powers between the executive and the judiciary” (ibid., p. 10).

The weakening of civil society has also contributed to Turkey’s democratic backsliding. A key factor in the dismantling of civil society is the fact that “freedom of assembly continues to be overly restricted, in law and practice through the recurrent use of bans of demonstrations and other types of gatherings” (European Commission, 2018a, p. 10).

The fact that civil society has been under continuous pressure, and that its organizations’ space to operate freely has continued to diminish, was evidenced at the Gezi trial and by the continued pre-trial detention of Osman Kavala, despite a ruling of the European Court of Human Rights calling for his release, in which the judges explicitly state that ““the prosecution’s attitude could be considered such as to confirm the applicant’s assertion that the measures taken against him pursued an ulterior purpose, namely to reduce him to silence as an NGO activist and human-rights defender, to dissuade other persons from engaging is such activities and to paralyse civil society in the country”” (Pillay, 2020, p. 3). And as civic discussion migrates from the town square to the timeline, the Turkish government is scrambling to assert control over online speech: “On Oct. 1, a far-reaching new law restricting internet freedom went into effect in Turkey. The law requires social media companies to appoint local representatives in Turkey and comply with draconian speech-restrictive conditions. And what if companies don’t comply? They will face bandwidth squeeze, exorbitant fines and prosecution” (Yuksel, 2020).

Widespread corruption is another factor that impedes Turkey’s compliance with international and European law. In particular, the Commission noted in 2018 that “The country has some level of preparation in the fight against corruption, but that the legal and institutional framework needs further alignment with international standards and continues to allow undue influence by the executive in the investigation and prosecution of high-profile corruption cases.” (European Commission, 2018b, p. 5). There was no improvement by 2020, when the Commission reported that “Regarding the fight against corruption, Turkey remained at an early stage and made no progress in the reporting period” (European Commission, 2020, p. 6). Overall, corruption is widespread and remains an issue of concern, specifically: “Limited accountability and transparency of public institutions have remained a matter of concern” and “the absence of a robust anti-corruption strategy and action plan is a sign of lack of political will to fight decisively against corruption…” (European Commission, 2019, p. 25).

In addition, the respect for and protection of human rights remain weak in Turkey, as reflected by a number of “key recommendations of the Council of Europe (CoE) and its bodies yet to be addressed by Turkey” (European Commission, 2018b, p. 4), and “derogations from its obligations foreseen by the European Convention on Human Rights and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights” (ibid., p. 6). In the same spirit, the Human Rights and Equality Institution of Turkey (HREI), which should act as the national preventive mechanism, “does not meet the key requirements under the Optional Protocol to the UN Convention against Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UN CAT) and is not yet effectively processing cases referred to it” (European Commission, 2020, p. 31). In 2019, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) found violations of the ECHR in 97 cases (of 113) relating mainly to freedom of expression (35), the right to liberty and security (16), protection of property (14), the right to fair trial (13), inhuman or degrading treatment (12), respect for private and family life and right to life (5). During the reporting period, 6,717 new applications were registered by the ECtHR. In January 2020, the total number of Turkish applications pending before the Court was 7,107. There are currently 677 cases against Turkey in the enhanced monitoring procedure. (ibid. p. 29). In fact, in 2018 and 2019, Turkey topped the list for number of European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) judgements regarding violations of freedom of expression (Molu, 2020, p. 17).

The Commission has attributed such violations to “systemic lacunas” and to deficiencies in the “institutional capacity of the Ministry of Justice” (2018c, pp. 5, 8, 10).

The examples of human rights violations are numerous. For instance,“Turkey continues to be an important transit and destination country for trafficking in human beings” (European Commission, 2020, p. 44); the “lack of credible and effective investigations into reported killings by the security authorities continues to be deeply worrying” (ibid., p. 31), “credible allegations of torture and ill-treatment continued to be reported” (ibid., p. 6), the “lack of legal personality of non-Muslim communities remains a serious issue” (ibid., p. 32), and “the procedural rights of journalists, including the right to a fair trial and the respect of the principle of the presumption of innocence were not always ensured” (ibid., pp. 33-34). President Erdoğan has made statements about a possible return of the death penalty, which the EU found unacceptable (European Parliament, 2018, p.2).

Benjamin Ward, Europe and Central Asia acting director at Human Rights Watch, adds that: “Turkish courts have convicted thousands of people in the past four years simply for speaking out against the president. The government should stop this mockery of human rights and respect people in Turkey’s right to peaceful free expression” (Human Rights Watch, 2018). Prosecutions under Article 299 of the Turkish penal code for “insulting the president” have risen dramatically, from 132 in 2014 to over 6,000 in 2017. Using the article to prosecute journalists, academics, juveniles and ordinary people for social media postings, as has been done since Erdoğan became president, is a “direct assault on freedom of expression and critical speech devoid of advocacy or incitement to violence” (ibid.).

Source: Human Rights Watch, 2018

In terms of human rights, special mention shall be made of gender equality, since Turkey ranks 69 out of 153 countries on gender equality, with a score of 0.328 in the 2015 United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) Gender Inequality Index. The inclusion and participation of women at all levels of society remains a key challenge. Despite the Turkish government’s ratification of the Council of Europe Convention on Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (Istanbul Convention), “its implementation remained flawed, and reports of violence against women continued to rise” (European Commission, 2018a, p. 7). In addition, “violence against women remains a serious concern, including deaths due to domestic violence and the so-called ‘honour’ killings”. On 20 March 2021, President Erdoğan issued a decree “dissolving Turkey’s obligations under the Council of Europe treaty, dubbed the Istanbul Convention”, which provides a comprehensive legal and social framework for addressing violence against women (Yackley, 2021a). His decision was condemned by human rights and women’s organizations, as well as by European Commission President von der Layen and HR/VP Borrell.

Concerning minorities, the state of affairs in Turkey is once again disappointing in comparison with European and international standards. As the Commission notes: “The rights of the most disadvantaged groups and of persons belonging to minorities need better protection” (2020, p. 7). For instance, “Roma continue to live in very poor housing, often lacking basic public services and relying on social benefits” (ibid.). Regarding the rights of people with disabilities, discriminatory legislative provisions which are “not compatible with EU acquis provisions” remain in force, such as restricted access to certain public professions (i.e. diplomat, judge, governor and prosecutor), while the penal code requires proof of a hatred motivation for disability-based discrimination (ibid., p. 39). Τhere are also “serious concerns regarding the fundamental rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people” (ibid.). On February 2, 2021 President Erdoğan lashed out at the country’s LGBT movement, praising the youth wing of his ruling AK Party for being bearers of the “glorious history of this nation” and for not being “LGBT youth” (BBC, 2021).

III. Regional Perspectives

4. Syria as a Launching Pad for Turkey’s Geopolitical Aspirations

Turkey hosts the largest population of Syrian refugees: an estimated 3.6 million, according to the UNHCR. However, since the beginning of the civil war in Syria, Turkey has seen an opportunity to expand its geopolitical footprint in the region while at the same time containing the influence of the Kurdish element in Northern Syria. The means it has employed to achieve its policy objectives are in direct conflict with international law and have provoked the condemnation of the EU and the US.

Specifically, unilateral military operations in Northern Syria have resulted in the occupation of Syrian territory. In addition, Turkey seems to have cooperated with paramilitary forces on the ground, like Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), that were part of the Al-Qaeda framework, while its commitment to capturing former ISIS fighters and bringing them to trial has been less than firm. To make matters worse, taking advantage of Syria’s grave socioeconomic conditions, Turkey has turned Northern Syria into a mercenary powerhouse which has been used to attain military goals in Syria and further afield—in Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh, for example. Finally, together with Russia and Iran, Turkey has advocated for the Astana process, weakening the framework defined by UN Security Council Resolution 2254.[7]

Since 2013, Turkey has behaved passive-aggressively towards the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad, allowing anti-Assad paramilitary groups, including jihadi groups such as ISIS, to grow in strength through the use of Turkish territory both as a source of recruits and as a crossing point for “weapons, supplies and people” smuggled into Syria (International Crisis Group, 2020a, p. 1). The number of Turkish citizens who took up residence in ISIS-held territories is estimated at 5,000-9,000, one of the largest numbers in absolute terms (ibid.). The Turkish state is partly to blame for this development, as “The Turkish authorities, like their counterparts in some other countries, adopted a relatively complacent view towards young people going to join rebels fighting Bashar al-Assad’s regime” (ibid., pp. 1-2). Other sources state that Turkey allowed “illegal pipelines transporting oil from Syria to nearby border towns in Turkey” (Phillips, 2016), while the New York Times reported that “behind the scenes, the conversations about the Sunni extremist group’s ability to gather vast sums to finance its operations have become increasingly tense since Mr Obama’s vow on Wednesday night to degrade and ultimately destroy the group. Turkey’s failure thus far to help choke off the oil trade symbolizes the magnitude of the challenges facing the administration both in assembling a coalition to counter the Sunni militant group and in starving its lifeblood” (Sanger and Hirschfeld, 2014).

The international coalition formed by the US in 2014 to defeat ISIS in Syria and Iraq managed to gradually contain and finally defeat it in March 2019 with the assistance of local allies, such as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in Syria, a multi-ethnic coalition of Kurdish, Arabic, and Christian fighters (Wilgenburg, 2020). However, Turkey was particularly concerned by the growing military presence of the SDF, as it was now dominated by the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG), which Turkey considers “an integral part of the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK)[…]” (Khalifa, 2021).

Consequently, Turkey quickly became enmeshed in a series of military campaigns[8] against the SDF in the main, in which it made use of the Syrian National Army (SNA), an umbrella organization for local militias that included “secularists, Syrian Turkmen, and Islamist nationalists, amongst others” (Morgan, 2020). Furthermore, Turkey seems to have cooperated closely with Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), a militia that previously acted as part of the al-Qaeda network in Syria. The International Crisis Group (ICG) reports that “although it [Turkey] officially designates the former al-Qaeda affiliate HTS as terrorist, this group fights in north-western Syria alongside Turkish-backed forces against the Syrian regime and thus benefits indirectly from Turkish aid” (2020a, p. 15). This policy of direct military intervention as well as interventions through proxies has resulted not only in the military occupation of Syrian territory, but also in grave human rights violations that include the displacement of thousands of people, changes in the demographic composition of the Turkish-controlled territories through forced population transfers, the confiscation of properties, illegal detentions and deportations. To make matters worse, Turkey has been using mercenaries from Syria “[…]who fought for the likes of ‘Islamic State’ and al-Qaida-affiliated militant groups” in order to pursue its geopolitical aspirations in the Middle East, North Africa and the Caucasus (Deutsche Welle, 2020b).

Specifically, according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), 137,000 people were displaced from the Afrin district due to ‘Operation Olive Branch’ in January-March 2018 (2018). In addition, the report released by the UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR) in June 2018 states that “civilians now living in areas under the control of Turkish forces and affiliated armed groups continue to face hardships, which in some instances may amount to violations of international humanitarian law and violations or abuses of international human rights law” (OHCHR, 2018, p. 1). For instance, the report stipulates that:

“Many civilians seeking to return to their homes have found them occupied by these fighters and their families, who have refused to vacate them and return them to their rightful owners. Others reported that they found their houses had been looted or badly damaged. OHCHR is concerned that permitting ethnic Arabs to occupy houses of Kurds who have fled, effectively prevents the Kurds from returning to their homes and may be an attempt to change permanently the ethnic composition of the area.

In addition to reports of looting and the seizure of real-estate and private property noted above, there have also been reports of civilian property being confiscated under the pretext that the person had been in some way affiliated with Kurdish forces.”

(ibid., pp. 6-7)

Human Rights Watch (HRW) confirmed parts of the UN report, stating that “Turkey-backed armed groups in the Free Syrian Army (FSA) have seized, looted, and destroyed property of Kurdish civilians in the Afrin district of northern Syria […]” (HRW, 2018). The Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic further revealed that “transfers of Syrians detained by the Syrian National Army to Turkish territory may amount to the war crime of unlawful deportation of protected persons (see para. 57 above). Such transfers provide further indication of collaboration and joint operations between Turkey and the Syrian National Army for the purpose of detention and intelligence-gathering” (2020, p.14).

In addition, there is strong evidence that Turkey uses Syrian fighters not only to expand its geopolitical footprint inside Syria, but also to enhance its military presence and influence in different war theatres, such as Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh (McKernan, 2020b), causing further instability and human rights abuses in other regions.

On Turkey taking advantage of the precarious socioeconomic conditions in Syria, USAFRICOM reports that “Turkey sent more than 5,000 Syrian mercenaries to support the GNA [Government National Accord]” in Libya (O’Donnell, 2020, p. 6), while sources within the SNA reported that “around 1,500 Syrian have so far been deployed to the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region in the southern Caucasus” (Cookman, 2020). Apart from creating further instability, Turkey has violated the International Convention against the Recruitment, Use, Financing and Training of Mercenaries that came into force in 2001, prohibits the use of mercenaries, and has been ratified by both Libya and Azerbaijan (for more on this, see UN Human Rights Special Procedures, 2018, p. 7; Morgan, 2020).

In terms of Turkey’s diplomatic activity in Syria, the country has opted for close cooperation with Russia and Iran since 2017 through the Astana process, thereby disregarding European and American voices and weakening the framework defined by the UN. The idea underlying the Astana process was to “formalize Russia’s dialogue with Turkey and Iran, who back a number of the armed groups involved on the ground in Syria” (Thépaut, 2020). In addition, “the summits also signalled to the world that Russia, Turkey, and Iran were the decisive players in Syria, because they alone were willing to take significant risks and use military force to shape political outcomes” (ibid.). Most importantly, the Astana process is:

“A set of bilateral discussions between Russia and military actors on the ground that are then bolstered by high-level political meetings. The process has been built incrementally, without a clear endgame beyond the creation of alternative tracks that are more favourable to Russia’s goals than to the framework defined by UN Security Council Resolution 2254[…] [T]he September 2018 Sochi deal on Idlib and the October 2019 deal on northeast Syria were negotiated bilaterally between Moscow and Ankara. The Astana format is built mainly around Turkey in order to pull Ankara further away from its Western partners. At the same time, however, this gives Erdoğan some leverage over Moscow. Such contrary dynamics make the Astana format less sustainable as Turkish and Russian interests in north Syria become less compatible.”

(ibid.)

Both the US and the EU have aired their discontent with Ankara’s policies in Syria; in some instances, they have also acted, albeit on differing scales and without being able thus far to forge a common position on Turkey’s disruptive behaviour in Syria. Specifically, the previous US administration under Donald Trump overturned key elements of the policy on Syria put in place by his predecessor, Barack Obama, most notably when it announced the hasty withdrawal of US forces from Northern Syria, and in particular from areas under SDF control, in October 2019 (Barnes and Schmitt, 2019). Its impact: “President Erdoğan was given a de facto green light to move in”, with Turkey carrying out “Operation Peace Spring” (Lowen, 2019). Despite Trump’s decision to withdraw US forces, which ultimately enabled Turkey’s operation, the US Treasury Department announced sanctions on Turkey’s ministries of National Defence, on the one hand, and Energy and Natural Resources, on the other, as well as on the Ministers for National Defence, Energy and Natural Resources, and the Interior (Hurriyet Daily News, 2019). Furthermore, Trump announced that he would end negotiating with Turkey over a $100 billion trade deal and raise tariffs on Turkish steel imports to 50% (ibid.). Similarly, NATO defence ministers symbolically condemned Turkey for its military incursion into northeast Syria, demonstrating Turkey’s diplomatic isolation in relation to the issue (Brzozowski, 2019).

On the European side, the reaction was strong and involved different institutions and actors. For instance, the European Parliament’s resolution stipulated that it:

“Regrets the fact that the Foreign Affairs Council of 14 October 2019 was unable to agree on an EU-wide arms embargo on Turkey; welcomes, nonetheless, the decision by various EU Member States to halt arms exports licencing to Turkey, but urges them to ensure that the suspension also applies to transfers that have already been licensed and to undelivered transfers; reiterates, in particular, the need for the strict application by all Member States of the rules laid down in Council Common Position 2008/944/CFSP on arms exports, including the firm application of criterion four on regional stability; strongly calls on the VP/HR, for as long as the Turkish military operation and presence in Syria continues, to launch an initiative aimed at imposing a comprehensive EU-wide arms embargo on Turkey, including dual-use technology goods, in view of the serious allegations of breaches of international humanitarian law; 10. Calls on the Council to introduce a series of targeted sanctions and visa bans to be imposed on Turkish officials responsible for human rights abuses during the current military intervention alongside a similar proposal for the Turkish officials responsible for the internal crackdown on fundamental rights; urges all Member States to ensure full compliance with Council Decision 2013/255/CFSP(4) on restrictive measures against Syria, and in particular the freezing of assets of individuals listed therein and restrictions on the admission of persons benefiting from or supporting the regime in Syria.”

(European Parliament, 2019)

Earlier, on 14 October 2019, the EU Foreign Affairs Council condemned

“Turkey’s military action which seriously undermines the stability and the security of the whole region, resulting in more civilians suffering and further displacement and severely hindering access to humanitarian assistance. It makes the prospects for the UN-led political process to achieve peace in Syria far more difficult. It also significantly undermines the progress achieved so far by the Global Coalition to defeat Da’esh, stressing that Da’esh remains a threat to European security as well as Turkey’s, regional and international security”

(2019)

Subsequently, the EU countries committed to suspending arms exports to Turkey, but stopped short of an EU-wide arms embargo (ibid.).

In addition, Germany’s Foreign Minister, Heiko Maas, argued that “we do not believe that an attack on Kurdish units or Kurdish militias is legitimate under international law” (Deutsche Welle, 2019b). Finally, the analysis of the European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS) on the impact of Turkey’s military operation in Syria on EU-Turkey relations paints a bleak picture. It argues that:

“What is new is not the fight against the PKK, but rather Turkey’s further strategic decoupling from two of its allies, the EU and the United States. This decoupling started in 2016, when the failed military coup in Turkey prompted President Erdoğan to reinforce his ties with Moscow. Since then, he has grown more authoritarian, using anti-Western rhetoric and making foreign policy choices contrary to the interests of the trans-Atlantic alliance. In light of the Trump administration’s withdrawal from Syria, Turkey’s military move might also be perceived as an attempt to fill a power vacuum in the region and jointly consolidate its influence there with its new ally, Russia.”

(Stanicek, 2019, p. 1)

5. Turkey’s Assertive Policies in Iraq as a Source of Instability

In the post-Saddam era, Turkey’s main political and military objectives vis-à-vis Iraq have been identified with militarily containing or defeating the PKK, supporting the sovereignty and integrity of Iraq as an answer to its own Kurdish problem (Taşpınar, 2007), and countering Iranian aspirations of greater influence in Shia-majority Iraq by supporting Iraqi Sunnis and Turkmens (Manis & Kaválek, 2016). It is indicative that when the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMU), Iranian-backed Iraqi paramilitary forces, opened the front west of Mosul in 2016 to recapture Tal Afar from ISIS, Erdoğan warned that: “If [the PMU] terrorizes Tal Afar, our response will be different.” (Ibid., p. 8).

In this context, Turkey has built numerous temporary bases in northern Iraq (Coskun, 2020), trained local Sunni Arab and Turkmen militia such as the Hashd al-Watani (Manis & Kaválek, 2016, p. 9), and conducted numerous operations inside Iraq, such as the ‘Claw-Eagle’ and ‘Claw-Tiger’ in June 2020.

Iraq experienced a surge in Turkish military operation in its northern provinces following the collapse of the ceasefire between Turkey and the PKK in 2015, and even more so after the defeat of ISIS in 2017 and the gradual convergence of Turkish and Iranian interests in Syria under the aegis of Russia. Indicatively: “Turkey and Iran confirmed for the first time that they are coordinating militarily against the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) and its Iranian affiliate, the Kurdistan Free Life Party (PJAK)” (Iddon, 2020).

Iraqi officials have condemned Turkey’s military presence again and again without any real consequences. For example, in 2015 Iraq announced that Turkey had 48 hours to “withdraw an influx of Turkish military deployed near the Islamic State stronghold of Mosul without the consent of the Baghdad government, and warned that it would ask the United Nations Security Council to force their removal […]. ‘Iraq has the right to use all available options’, said a statement from the then Prime Minister, Haider al-Abadi” (Leigh & Nissenbaum, 2015). In 2017, Abadi reiterated his call for the withdrawal of Turkish forces as a precondition for improved Iraqi-Turkish relations (Al Jazeera, 2017). In 2020, Iraqi PM Mustafa al-Kadhimi said that Turkey’s interference in Iraq was unacceptable (Haboush, 2020).

What is worrisome is the response from the Turkish side. For instance, in 2016, President Erdoğan responded to al-Abadi thus: “Now he [al-Abadi] says ‘withdraw from here’. The army of the Republic of Turkey has not lost its standing so as to take instructions from you. You are not my interlocutor, you are not at my level.” (Middle East Eye, 2016). More recently, the situation was aggravated by the death of 13 Turkish citizens in the Gare region of northern Iraq. In response, on 15 February 2021, Erdoğan threatened to expand Turkish operations in Sinjar aimed at destroying the PKK and its affiliates: “From now on, nowhere is safe for terrorists, neither Qandil nor Sinjar nor Syria”, Erdoğan said (Tastekin, 2021).[9] This is the area where the Yazidi community suffered ‘genocide’ at the hands of ISIS, according to the UN (Abouzeid, 2018). In addition, the prospect of a unilateral Turkish incursion into this area has provoked resentment in a number of Iranian-backed militias in Iraq, potentially complicating the political and security dynamics in Iraq.

“A unilateral Turkish incursion would have severe political consequences, particularly as Iraq is preparing for parliamentary elections. It would undermine the political victory the Sinjar Agreement afforded to Kadhimi, burnish the image of the PMUs and other militia groups as defenders of Iraq at the central government’s expense, and hamper the return of vulnerable displaced Yazidis to Sinjar. Military action would also seriously damage Turkey’s reputation in Iraq. In addition, it could also hamper progress on issues such as intra-Kurdish talks in Syria, thereby strengthening the PKK in the country.”

(Younis, 2021)

The U.S. State Department recently noted that Turkish air strikes in Iraq wounded at least six civilians and killed three in 2020 (2021, p. 3). The EU High Commissioner has noted that “While the EU considers the PKK a terrorist organisation, countries in the region are encouraged to coordinate bilaterally anti-terrorist activities, as well as to act proportionally and in full respect of the rule of law.” (European Commission [High Representative of the EU for Foreign and Security Affairs], 2021, p. 21).

To conclude, despite Turkey’s expressed commitment to the sovereignty and integrity of Iraq as a response to its own Kurdish problem, its rhetoric and deeds are in direct conflict with this commitment. Furthermore, Turkey’s unilateral actions violate international law and create dynamics that can bring more instability to the fragile political and military environment of Iraq.

6. A Troublesome Neighbor in the Eastern Mediterranean

Turkey has abandoned the “security-based” foreign policy it pursued from the mid-2000s (which was limited to geopolitical ambitions vis-à-vis its periphery), and moved towards an assertive “power-based” foreign policy which has translated into the same pattern of aggressive behaviour in Cyprus and the Aegean as in Syria, Libya and Iraq. This assertive strategy is also revisionist and embraces the “geography of the Ottoman empire”. By mid-2020, it was evident that Turkey had become a revisionist outlier which was attempting to limit, if not undermine, multilateral regional institutional arrangements that did not conform with Turkey’s aspirations.

Considering himself the leader of a global power and a “central state” in the international system, Erdoğan could not tolerate the emergence of the Republic of Cyprus (which Turkey does not recognize) as an independent player in the Eastern Mediterranean. There are numerous examples of President Erdoğan acting provocatively and illegally towards Cyprus and Greece.

6.1 Acting Illegally against Cyprus’s Sovereignty

With regard to Cyprus, Turkey has reacted harshly both to the delimitation agreements on Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) which the Republic of Cyprus has concluded with Egypt (2003), Lebanon (2007) and Israel (2010), and to the planned construction of the EastMed natural gas pipeline. Turkey has claimed that these security arrangements regarding the exploration, monetization and transportation of Cypriot natural gas are designed to isolate Turkey from energy developments in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The discovery of gas fields off the coast of Cyprus has also exacerbated the tensions between Turkey and the Republic of Cyprus that had existed since the Turkish invasion of Cyprus and the division of the island in 1974 (European Parliament, 2020b, p.2). Indeed since the discovery of offshore natural gas reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean in the early 2000s, Turkey has challenged its neighbours with regard to the delimitation of their Exclusive Economic Zones and destabilized the whole region through its illegal exploration and military interventions in violation of international law (European Parliament [Committee on Foreign Affairs], 2020, p. 18).

More specifically, Erdoğan’s strong counter-offensive against Cyprus has included Turkey’s decision to purchase its own drilling vessels and begin its own explorations (in 2017 and 2018) in an area legally delineated as part of the Republic of Cyprus’ Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ); in some cases, these explorations were conducted in accordance with a permit issued by the internationally unrecognized “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” (TRNC). In early October 2019, tensions rose further when Turkey deployed one of its drillships in an area the exploration rights to which Cyprus had already given to international oil companies (ibid., p.3).

Tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean region rose further in 2020 as a result of Turkey’s illegal actions and provocative statements challenging the right of the Republic of Cyprus to exploit hydrocarbon resources in its own EEZ. Turkey deployed two drilling and two seismic vessels within the EEZ of the Republic of Cyprus, including areas that have been licensed to European oil and gas companies by the Government of Cyprus. The Turkish Armed Forces accompanied the drilling and seismic ships during their operations, posing a grave threat to the security of the region (European Commission [High Representative of the EU for Foreign and Security Affairs], 2021, p. 7).

The European Council has closely monitored and strongly condemned Turkey’s illegal drilling activities in the Eastern Mediterranean since March 2018, while also expressing solidarity with both Cyprus and Greece (European Parliament, 2020a, p.3). Council conclusions have deplored Turkey’s continuing drilling operation west of Cyprus and the launch of a second drilling operation north-east of Cyprus, both within Cypriot territorial waters (ibid.).

In light of Turkey’s unauthorized drilling activities in the Eastern Mediterranean, in July 2019 the Council decided to suspend negotiations with Turkey on the Comprehensive Air Transport Agreement, not to hold the EU-Turkey Association Council and further meetings of the EU-Turkey high-level dialogues for the time being, to endorse the Commission’s proposal to reduce the pre-accession assistance to Turkey for 2020, and to invite the European Investment Bank to review its lending activities in Turkey, in particular with regard to sovereign backed lending. (European Commission [High Representative of the EU for Foreign and Security Affairs], 2021, p.3).

The EU also adopted a framework for targeted measures against Turkey in November 2019. In February 2020 it decided to add individuals to the list of designations under this sanctions framework. Furthermore, following Turkish drilling in Cyprus’ territorial waters and military operations in Libya, a new cut in EU funds earmarked for 2020 from €150 million to €400 million has been under consideration (European Parliament, 2020b, p.7).

Turkey’s foreign policy has increasingly clashed with the EU’s priorities under the Common Foreign and Security Policy. Deeply concerned by Turkey’s provocative behaviour in the Eastern Mediterranean and the risk of a military escalation this entails, the EU has condemned Turkey’s illegal activities in Greek and Cypriot maritime zones, which violate both the sovereign rights of EU Member States and international law. It has also expressed its full solidarity with Greece and the Republic of Cyprus and urged Turkey both to settle disputes peacefully and to refrain from any unilateral and illegal action or threat (European Parliament [Committee on Foreign Affairs], 2020, p.7).

The EU has repeatedly stressed the need to respect the sovereign rights of EU Member States, which include entering into bilateral agreements and exploring and exploiting their natural resources in accordance with the EU acquis and international law, including the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. Moreover the EU has called on Turkey to commit itself unequivocally to good neighbourly relations, international agreements and the peaceful settlement of disputes in accordance with the United Nations Charter, having recourse, if necessary, to the International Court of Justice. In October 2020, the European Council called on Turkey to accept Cyprus’ invitation to engage in dialogue with the objective of settling all maritime-related disputes between Turkey and Cyprus.

Unfortunately, the prospects of a peace settlement, especially one based on a bizonal and bicommunal federation, seem more remote today than ever following both the election of Ersin Tatar, a fierce supporter of a ‘two-state solution’, as the new leader of the Turkish-Cypriot community and the provocative actions of President Erdoğan with the opening of the ‘ghost town’ of Varosha by the Turkish army. Turkey’s support for a two-state solution on Cyprus diverges from both the United Nations Security Council Resolutions and the EU position, which favour a bizonal and bicommunal federation (European Commission [High Representative of the EU for Foreign and Security Affairs], 2021, p.3). Specifically, the European Council “[C]ondemns Turkey’s unilateral steps in Varosha and calls for full respect of UN Security Council Resolutions 550 and 789. The European Council supports the speedy resumption of negotiations, under the auspices of the UN, and remains fully committed to a comprehensive settlement of the Cyprus problem, within the UN framework and in accordance with the relevant UN Security Council Resolutions and in line with the principles on which the EU is founded. It expects the same of Turkey” (European Council, 2020a, p.12).

Most recently, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy stressed that Turkey’s unilateral actions in the fenced-off area of Varosha, as well as its repeated statements, were “directly questioning the agreed basis for the solution to the Cyprus problem as provided by the relevant United Nations Security Council Resolutions (UNSCR), the latest of which was adopted on 29 January 2021 (UNSCR 2561) (European Commission [High Representative of the EU for Foreign and Security Affairs], 2021, p.3). On 25 March 2021, the European Council reiterated its commitment “to a comprehensive settlement of the Cyprus problem in accordance with the relevant UNSC resolutions (notably 550, 789, 1251)” (2021, p. 7).

6.2 Challenging Greece’s Sovereignty and Sovereign Rights

The already strained relations between Turkey and NATO-ally Greece turned dangerous after Turkey’s provocative and illegal actions in the Eastern Mediterranean. Turkey’s assertive behaviour towards Greece has included the signing of a military and maritime zone delimitation agreement with Libya’s Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA) in November 2019. This outlandish agreement sparked an indignant reaction from Athens, as it infringed upon maritime zones adjacent to the Greek islands of Crete, Kassos, Karpathos, Rhodes and Megisti, purposely violating the principle of international law that islands are taken into account when delineating an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). In December 2019, the European Council unequivocally reaffirmed its solidarity with Greece and Cyprus in relation to actions by Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Aegean Sea. It stressed that the Memorandum infringed upon the sovereign rights of third states, does not comply with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, and cannot produce any legal consequences for third states (European Council, 2019, p. 4).

Moreover, Turkey has deployed a research vessel escorted by several warships in a non-delineated area that Greece considers to be within its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The unilateral decision by Turkey to conduct research activities in a non-delineated zone was illegal under the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention (UNCLOS, Article 121). Turkey’s research activities lasted for several months (from August to November 2020) and brought Turkish ships to within a few miles of Greek islands such as Crete and Rhodes. In addition to these illegal and provocative actions in the Eastern Mediterranean, Turkish senior officials introduced inflammatory rhetoric against Greece and certain EU Member States, along with the fiercely nationalist narrative of the Mavi Vatan [Blue Homeland].

It is worth noting that Turkey’s brinkmanship in the Eastern Mediterranean followed the agreement concluded between Greece and Egypt at the start of August 2020, which was in full accordance with the provisions of the UNCLOS. The delineation of maritime zones between Greece and Egypt infuriated Ankara, as it had successfully scuppered both the illegal and geographically surreal MoU between Turkey and Libya, and, most importantly, Turkey’s maximalist Blue Homeland narrative.

In late February-early March 2020, Turkey decided to promote short-sighted policies on the Greek-Turkish borders on the river Evros in northern Greece through the “instrumentalization” of migrants and refugees with the aim of blackmailing the EU and securing additional economic aid along with other concessions, including visa liberalization for Turkish citizens. In a statement, the EU Council—representing the 27 foreign ministers—said the Council “expresses its solidarity with Greece” and “strongly rejects Turkey’s use of migratory pressure for political purposes”. Moreover, the EU Council stated that

“This situation at EU’s external borders is not acceptable. [The Council] expects Turkey to implement fully the provisions of the 2016 Joint Statement with regard to all Member States. […] The EU and its Member States remain determined to effectively protect EU’s external borders. […] Illegal crossings will not be tolerated. […] In this regard, the EU and its Member States will take all necessary measures, in accordance with EU and international law. […] Migrants should not be encouraged to endanger their lives by attempting illegal crossings by land or sea. […] The Council calls upon the Turkish government and all actors and organizations on the ground to relay this message and counter the dissemination of false information”

(European Council, 2020c)