The second PAVE-ELIAMEP Policy Paper puts the relationship between media and radicalisation under the microscope. It investigates the role and influence of online social media and traditional media in (de) radicalisation processes in North Macedonia.

The fieldwork conducted by ELIAMEP’s PAVE research team in North Macedonia identified the media, and online social media, as “key” radicalisation risks:

The online social media space is perceived as an environment that provides more opportunities for inciting extremist views, and as such represents a serious threat to community security and to public order in general.

The unregulated online media environment that allows unverified content to be disseminated, including hate speech, is viewed as a key factor in community vulnerability.

- For extremist groups of all sorts, the internet has become their most important communication, mobilisation, and propaganda tool.

- Despite the efforts of the competent authorities to have social media pages with extremist content taken offline, the digital recruitment tactics of extremist groups supporting various types of extremism are still visible on several social media platforms.

- Social media also play an important role in fostering counter-narratives and re-directing users to safer online environments, but their potential does not seem to have fully exploited by the relevant P/CVE actors, who are not well-suited to producing counter-narratives.

- One very concerning outcome of the analysis of the online content is that the pages promoting radicalisation are far more numerous than those promoting de-radicalisation.

- The overall impression given by the analysis of the online content is that radical groups are surgically targeting their audiences in line with their objectives and the space in which they operate.

- When it comes to the traditional media, it seems that they do not play a significant role in promoting religiously-inspired radicalisation in North Macedonia. However, patriotic and nationalist journalism is evident in both Albanian- and Macedonian-language media, expressed primarily through pieces which foster ethno-nationalist extremism.

Read here in pdf the second PAVE-ELIAMEP Policy Paper by Bledar Feta, P/CVE Researcher and member of ELIAMEP’s PAVE project research team, Ioannis Armakolas, Associate Professor, University of Macedonia; Head of ELIAMEP’s South-East Europe Programme and ELIAMEP’s PAVE project Head of Research, and Ana Krstinovska, Research Fellow, member of ELIAMEP’s PAVE project research team.

You can also read the first PAVE-ELIAMEP Policy Paper which examines the factors or gaps that hinder or foster community resilience against violent extremism in North Macedonia here.

Introduction

This policy paper is a complimentary publication to the Working Paper 5: Online and Offline (De)radicalization in the Balkans jointly produced by the Kosovo Centre for Security Studies (KCSS) and ELIAMEP’s South-East Europe Programme in the context of Horizon 2020 PAVE Project. This PAVE-ELIAMEP Policy Paper 2 puts the relationship between media and radicalisation under the microscope, investigating the role and influence of online social media and traditional media in (de) radicalisation processes in North Macedonia.

The fieldwork conducted by ELIAMEP’s PAVE research team in North Macedonia identified the media, and online social media in particular, as key radicalisation risks. All the interviewees agreed that the online space and new technologies are effective tools in the hands of malicious actors who intend to disseminate their narratives further and radicalise parts of society. The online social media space is perceived as an environment that provides more opportunities for inciting extremist views, and as such represents a serious threat to community security and to public order in general. These security threats acquired new and additional dimensions during the COVID-19 pandemic, mainly because people had to lead their lives entirely online. In this context, the new technologies provided extremists with new opportunities. The conclusion is that extremists introduced innovations faster than the official state authorities could respond to them, and increased their digital advantage as a result. Traditional media is not seen as a tool that promotes radicalisation in the country, but the problematic reporting of developments relating to radicalisation and efforts made to link specific ethnic groups to specific types of extremism are considered to be a factor that works against community-level prevention and resilience-building.

The purpose of this policy paper is to show the role and relevance of online social media and traditional media in and to (de) radicalisation. It also investigates the role of virtual communities as a tool employed by radical groups to attract supporters, analysing both their targeting policy and the online community’s reactions to their extremist content. We argue that preventing radicalisation at the community level requires that the de-radicalisation opportunities which social media present be better and more fully exploited. Social media could play a key role in fostering counter-narratives aimed at deconstructing the extremist narratives and re-directing online users to safer online environments. Greater cooperation between the traditional media and counter-terrorism authorities is more essential than ever, while establishing standards and guidelines for the media’s reporting of news related to extremism will definitely help build community resilience against radicalisation processes.

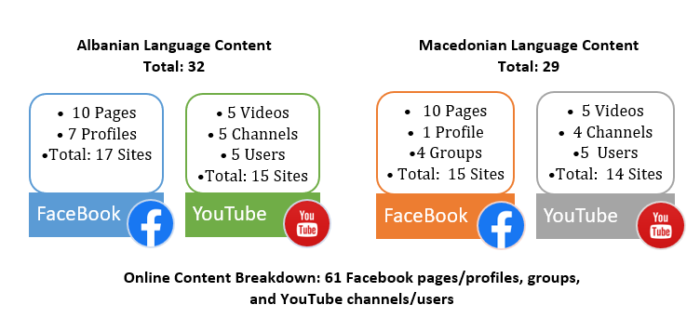

The findings of this policy paper draw on four focus group discussions and 29 semi-structured interviews conducted during 2021 at two field sites in North Macedonia. ELIAMEP’s South-East Europe Programme team conducted research in the municipalities of Tetovo and Kumanovo as well as in Skopje. Specifically, the team organised two focus group discussions in each municipality and conducted 29 semi-structured interviews with civil society activists/members, politicians, religious community leaders, public servants (in the police, education, social work and departments of social security), journalists and other media professionals, academics and other experts. For the analysis, the team adopted a comparative research method with a cross-municipal study that included desk research and an interpretative approach to fieldwork data. In parallel with their analysis of the field data, the research team also conducted a discourse analysis of online content. In total, the team analysed 61 Facebook pages, groups and YouTube channels, 29 of them in the Macedonian language and 32 in Albanian. The online content supporting violent extremism was subject to a structured content analysis. Special attention was paid to the interaction with the extreme content, in an effort to measure its appeal to users of online social networking platforms.

The search on Facebook, YouTube and Google was based on keywords aimed at identifying specific content related to the abovementioned events and stakeholders, but it also included keywords of a more general nature usually associated with different types of extremism. A rough initial analysis of the contents—and especially of Facebook profiles, groups and pages along with YouTube channels—helped to determine which sources were to be included in the corpus for a detailed discourse analysis. The material singled out as featuring extremist content was added to a database containing information on the type/format of content associated with the identified source, its title, key protagonists, affiliation (if known), physical location (if known), and language used. Then, using textual content analysis, the key messages and narratives were analysed and categorised according to the type of extremism. The interactions with the target audience (shares and reactions) were quantified and the comments to the content were tagged as being supportive of, neutral, or critical of the content.

The utilisation of media by radical groups in North Macedonia

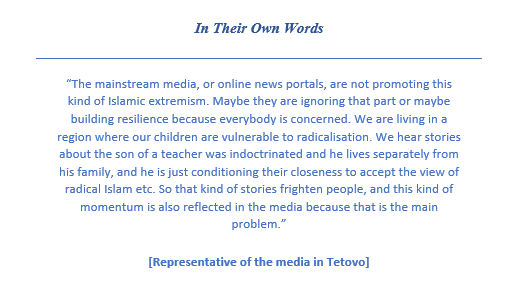

The fieldwork research established that traditional mainstream media in North Macedonia have not promoted religiously-inspired radicalisation. Local media have chosen to ignore the issue, since local stories about the indoctrination of young people into radical Islam have tended to alarm the local population.[1] This kind of approach is reflected in the local media, with the majority of outlets publishing mainly neutral articles about the criminal prosecution of foreign fighters, and thus avoiding any effort to influence the public negatively or positively. Currently, both Macedonian- and Albanian-language media and portals mainly publish translated version of articles from European media, providing little in the way of thorough analyses.[2] Ethnic Albanian interlocutors stressed that there are some Macedonian-language media with a strong patriotic and nationalist tone which are trying to connect the phenomenon of Islamist radicalisation exclusively with ethnic Albanians.[3] Efforts to communicate that this kind of extremism does not relate exclusively to ethnic Albanians are to be found mainly in the Albanian-language media. There have been several well-publicised cases of Orthodox Christians who decided to convert to Islam and became radicalised. One prominent example is the case of Stefan Stefanovski, an Orthodox Christian medical student who accepted Islam and became radicalised.[4]

Nationalistically-inclined journalism can be found in both Albanian- and Macedonian-language media, and it is mainly expressed in articles and commentaries that employ extremist language, foster ethnic nationalism, and incite inter-ethnic hatred. Journalism that takes a nationalist stance to extremism usually relates to the coverage of grassroots episodes relating to radicalism, with polarising effects for the local community, and articles reporting polarising nationalist statements by local political leaders. Some journalists tend to deviate from the objective of neutral reporting in an effort to play on their ethnic communities’ nationalistic emotions. They employ different forms of nationalist coverage, depending on whether they want to portray their side as belonging to the side of extremists or to the side of victims. This kind of media content triggers nationalistic rhetoric, creating plenty of scope for exploitation by extremist groups.

There has been a notable change in the reporting style of North Macedonia’s mainstream media over the past decade. Previously, journalists deemed it appropriate to underscore the ethnic background of people in the news, which in some cases fed into stereotypes, leading to the perception that a single ethnic community was associated with certain negative phenomena such as violence or crime and encouraging reciprocal radicalisation.[5] However, in recent years, following numerous projects and initiatives aimed at strengthening ethical journalism, the ethnicity has in most cases been replaced by the places of residence of perpetrators and victims (e.g. a man/woman/students from Skopje/Tetovo/Gostivar/Kumanovo, etc.) However, given the existing legal vacuum, while ethical reporting is mandatory for traditional media and violations of journalistic standards can lead to fines and sanctions, online news portals remain outside the legal framework, enabling them to continue exploiting fragile inter-ethnic relations to increase their readership.

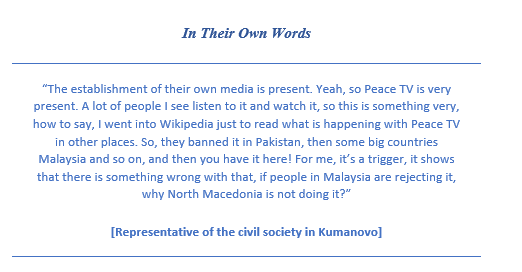

Importantly, the mainstream media in North Macedonia have reduced the media space that can be exploited by extremist groups, despite efforts by the latter to penetrate traditional media in order to disseminate their narratives. This is why local journalists and media have been targeted by radical groups. The failure of extremist groups to influence the mainstream media has led radical Islamists, in particular, to create their own media channels. In the competition for the “hearts and minds” of local Muslims, radical elements (such as Salafists) have a large repertoire of tools at their disposal. They have their own traditional and news media that communicate radical messages tailored to local Muslim communities, whom they reach through satellite transmission. Their media approach has the potential to influence specific societal groups, promoting their alternative perceptions of religion, society, and politics.

Even though they have resources and their own tools, both the state and the official Muslim authorities fail to produce adequate counter-narratives. Inadequate research has been conducted on the narratives Salafists produce, while the response to their agents, who are intelligent individuals who appear normal and know how to appeal to the local communities and how to make their message attractive, has been inadequate. Even though media established by radical Islamists does have some influence on local communities, and especially on middle-aged and elderly people who rely more on television for their information, their appeal is not comparable in popularity and influence of online social media, which appeal far more to the younger generations.

Online social media platforms play an ever more central role in radicalisation processes in North Macedonia. Social media and their use by radical groups, individual members and potential supporters provide avenues for accessing information about radical groups and their activities. The social media strategy implemented by radical Islamists is granular in nature. It centres on maintaining a prominent presence on open social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, through the posting of stories and videos which promote their narratives. However, their social media presence encompasses a far broader portfolio of activities focused on the creation of small communities; they are an excellent tool in the hands of radical groups seeking to “fish” supporters online.

After the police operations that left several individuals, including some imams, in jail for recruiting ISIS fighters, the nature of these pages has changed significantly. However, while pages making open calls to violence have been shut down, the authorities have not managed to eradicate radical elements from social media. Some of these pages have been re-opened by the same administrators under different names, and continue to spread extremist ideas camouflaged beneath a humanitarian disguise.[6] The co-existence of humanitarian and extremist content provides cover, allowing them to evade identification by the authorities. Currently, various Facebook profiles and YouTube channels continue to host the videos of radical imams from North Macedonia.

The biggest traffic in extremist ideas seems to take place in closed groups on Facebook and Telegram, while some radical groups use specific websites (“internet archive”, “files.fm”, “ok.ru”, etc.) to upload long sermons by radical imams and teachings by radicalised individuals abroad translated into Albanian. Over the last few years, online gaming has boomed, and it is also used by radicals to gradually attract gamers to radical narratives and groups. Computer games that are played online through websites and virtual communities are used to target youth, specifically in an attempt to interest them in the goals of radical groups with a view to their future recruitment.

TikTok has also emerged as a tool used by those who want to use online spaces to produce, post, and promote hate and extremism. Extremists from both the ethno-nationalist and radical Islamist space are using their accounts to promote their respective narratives. Internet portals play an important role in terms of information sharing, since they are not bound by the same rules as the traditional media and their journalists, who are accountable to the Agency for Audio and Audio-visual Media and the Council for Media Ethics. This gives extremist individuals ample opportunity to share their ideas through the established “grey” channels and through social media. Since social media remain outside the regulatory framework, they offer a favourable environment for the dissemination of hate speech and disinformation, despite a couple of interventions which the Ministry of Internal Affairs has made against people expressing hate speech online, following complaints and within the general legal framework addressing hate speech.

While channels and contents which present radical views in different formats (text, images, videos) on an occasional or regular basis abound on social media, those platforms have not been adequately exploited by those whose aim is de-radicalisation. Indeed, the efforts to deal with the extremist internet and produce adequate counter-narratives and content have failed to produce results. For its part, the traditional media have been far from active in building resilience; this is because some media, and local media in particular, lack the know-how and capacity required to implement projects that will produce the desirable results. Projects implemented by civil society are currently seeking to fill this gap. A prominent example is the project entitled “Building resilience against violent extremism through reinforcing journalists, media and government officials”, which aims to increase the media’s capacity to provide objective reporting on issues relating to violent extremism.[7]

Overall, the Islamists’ media policy seems to have been successful at winning the hearts and minds of Albanians in North Macedonia and in promoting their narratives to the public at large. Their strategy works in two directions: Firstly, they set up their own traditional media with a view to targeting elderly people in the main, who are not internet users Here, they aim to produce user-friendly content for this target group and to challenge any criticism from the local media. Secondly, they use social media with a view to building a positive narrative about radical Islam among young Albanians and to recruiting followers. While their traditional media, like Peace TV, have helped accelerate radicalisation among members of the community, their social media seems to have been the primary tool in mobilising individuals to join extremist groups. User-to-user online communication seems to increase the likelihood that radical groups will be successful at mobilising and radicalising individuals. Many interviewees view the influence of social media on radicalisation processes as significantly high.[8] In contrast, both traditional and social media are seen to influence the process of building resilience in the community to the same extent. However, most of the interviewees believed that local and national authorities in North Macedonia do not have a firm grasp of the role both traditional and social media can play in the de-radicalisation process.

The role of virtual communities as a tool used by radical groups to recruit supporters

Many of the interviewees in both Tetovo and Kumanovo confirmed that radical groups in North Macedonia are using the internet widely to promote involvement through the creation of virtual communities.[9] This trend was also substantiated by the analysis we conducted of Facebook pages and YouTube channels in both the Albanian and Macedonian languages used by ethno-nationalists and radical Islamists. The structure of these pages, their content, and the tone of their posts revealed the intention to radicalise social media influencers and thereby create a sense of online belonging based on rational and logical argumentation, which proclaims the fight for common goals.

The promotion of discourses that seek to dehumanise the enemy (e.g., the West for the radical Islamist groups; Albanians, Greeks and Bulgarians for the ethno-nationalist Macedonian groups; ethnic Macedonians and Serbs for the Albanian ethno-nationalist groups; and immigrants or LGBT people for the far-right extremist groups) and justify the ideology of these groups contribute to a community of validation that exists for current and potential members. These groups try to associate involvement in their virtual community with multiple benefits, including the creation of a sense of belonging and the perception of enjoying a special status or power. Members of the virtual community share common values and can recognise each other on the basis of the activities they share an ability that can help them expand their network through the inclusion of new followers, members and sympathisers.[10]

The language used by social media influencers calls, implicitly or explicitly, for the creation of both online and offline communities of like-minded individuals. They usually address the audience as “brothers and sisters” and point out the necessity of achieving unity in order to win the battle or promote the cause. There are examples of “defector” brothers and sisters who have been misled and taken the wrong path, having become alienated from their community, but community leaders usually express a willingness to allow them to redeem themselves and to accept them back. Video appearances show that the members of these groups wear the same, custom-made T-shirts with the organisation’s logo and, in some cases, apparel which resembles military uniforms. Many of these pages include contact details and information on how to join the groups or participate in activities organised by them. The encouragement given to virtual followers to participate in online support activities helps new followers penetrate further into the online structures of radical organisations. The supporters of radical Islamist groups are very active in this direction. Individuals from North Macedonia re-upload and reshare previously published videos of sermons by imams who promote the interpretation of radical Islam.

One other very significant dimension of virtual communities is their use as online spaces for increasing the interaction of supporters with the localities where they live. Online communities use chat rooms, mailing lists, and fora to facilitate communication between people who live geographically close to one another, allowing radical groups to form both online and offline networks and bonds. However, the formation of interpersonal relationships and the adoption of the prevalent ideology within the online community does not mean that every member will necessarily become radicalised. Our research has shown that involvement as an active member of a radical group is a gradual process. While many members participate in earlier phases, which include online discussions, they may never move on to the next level and become official members of extremist organisations. Other members are more actively engaged through the dissemination of information and the communication of ideologies in encouraging the active involvement of others in the online community. All these activities potentially facilitate the recruitment of individuals to specific extremist groups.

All in all, through the creation of virtual communities, the internet provides radical groups with an effective way to bring their “cause” to the public. As exemplified by the analysis of the online space, ethno-nationalist, radical Islamists, and far-right extremist groups from North Macedonia retain an interested body of supporters in virtual communities with a large number of registered followers. When it comes to community-based counter-narrative initiatives, the majority of interviewees recognised that communities could play a significant and useful role in developing alternative narratives to violent extremist propaganda, especially in countries like North Macedonia, where the population is unlikely to trust messages which come directly from the government.

However, this area remains unexploited by both governmental authorities and community-based NGOs. The online counter-messaging material is insufficient to allow us to draw a clear conclusion on how the social media influencers who promote counter-narratives in North Macedonia operate. The general perception is that they employ a peer-to-peer approach, using personal messaging on applications like messenger or WhatsApp to steer people who have been attracted to extremist narratives onto a different path.

Audiences and populations targeted by extremist groups in North Macedonia

The efforts of radical groups to influence specific populations in North Macedonia to promote their goals show that the extremists’ targeting policies follow a common and predictable pattern, aligning with the space to which these groups belong.[11] Radical Islamists mainly target the Albanian Muslim population of North Macedonia. However, many of their pages adopt a pan-Balkan agenda in an effort to influence all the Albanian populations in the region. Their main message is the need to protect Islam from the injustices which the West and other religions such as Orthodox Christianity, Catholicism and Judaism are committing against Muslim populations.

The online pages run by radical Islamists give the impression that their administrators are engaged in an online battle to identify those Muslims, especially young people, who have experienced ethnic conflict and polarisation, the inequality caused by uneven economic development and modernisation, disillusionment with local political representation, or frustration with the mixed results of integration into the West. These populations are considered more vulnerable to the radical Islamist narratives circulating in the online space.

The Albanian diaspora is also targeted by radical Islamist groups. In one of his videos, the Albanian imam from Kumanovo, Sadullah Bajrami, talks about immigrants’ obligation to visit their home country.[12] In his message to the Albanian diaspora, the imam says that “Immigrants should visit their country, their parents, and their brothers because this is an obligation that stems from their religion. Performing this obligation will cleanse them of their sins”. In this video, one can clearly identify Bajrami’s efforts to mobilise the Albanian diaspora and strengthen their bonds with Islam.

The Albanian population is not the radical Islamists’ only target in North Macedonia. There are pages and groups in the Macedonian language which advocate the superiority of Islam over other religions in an effort to convince ethnic Macedonians to follow their ideology.[13] The fieldwork in Tetovo and Kumanovo revealed that radical Islamist groups have managed to some extent to build a positive narrative among ethnic Macedonians through their online influencing tools. This is reflected in the considerable number of ethnic Macedonians who have converted to Islam.[14]

When it comes to the ethnic Macedonian nationalist groups, there are pages and groups which advocate for the reconciliation and unification of all ethnic Macedonians, regardless of their political affiliation, ideology, religion or other attributes, in order to protect national interests.[15] However, specific messages focus on the protection of Macedonian language and the Orthodox faith as the defining features of national identity.

Some ethnic Macedonian Orthodox priests are closely involved in societal events, and a small number are even comment on political developments on a daily basis. With the exception of a few priests who are regularly active on social media, the clergy usually involve themselves on an ad-hoc basis and in relation to issues which seem topical and important to their congregations (e.g., the referendum on the Prespa Agreement, COVID-19 measures affecting holy communion, which in the Orthodox liturgy is conducted using the same spoon for all, the Pride parade etc.).[16]

While the positions of all involve protecting the national identity and the Orthodox religion as its cornerstone, they differ in their preachings on how best to achieve this. The official position of the Orthodox Church of North Macedonia (Македонска православна црква—MPC) is to respect diversity of opinion, but to stay away from politics; from time to time, the MPC also publically distances itself from radical statements made by some of its priests. One example is the statement made by father Agatangel to the effect that the negotiations with Greece should not continue because politicians “are not authorised to negotiate questions pertaining to Macedonian history, language, name and identity”.[17]

Another official disclaimer followed the Facebook post by Father Ivica Todorov in relation to Soros’ mission and activities (i.e., financing LGBT and abortion).[18] Father Ivica Todorov is an active Facebook user with over 7,000 followers. He actively posts in many groups and on pages with ethno-nationalist content. He is one of the most committed opponents of the country’s new name, North Macedonia, but advocates the sort of legal and institutional resistance that can only come about through political change; hence his public support for the opposition VMRO-DPMNE’s candidate in the last presidential elections.[19]

Although radical priests seem to be a rarity on Facebook, there are occasional public appearances by members of the Orthodox clergy which include extremist rhetoric and hate speech. One of them, Stefan Zdraveski, is an active Facebook user who also seems to be linked to the “Slovo protiv sektite” (Teachings against heresies) Facebook page which, in addition to preaching and sharing sacred texts, occasionally posts radical content. However, individual clergymen of this sort seem to be rather marginal, and most priests seem to stick in their official appearances and online media to the official positions of the MPC, which are highly conservative but not necessarily extremist and which do not propagate violence. There have been deviations, as was the case with an influential and high-ranking church official, Jovan Vranishkovski, but he was fired from the MPC due to his pro-Serbian sympathies and ended in prison. The citizens who actively practice their religion are most vulnerable to the narratives employed by the priests, and they are more committed to religious causes than to national ones, with priests serving as points of reference for many of them.

The Albanian ethnο-nationalist groups target all the Albanian populations in the Western Balkans.[20] There are many pages that look to the unification of all Albanian-inhabited areas in the Western Balkans into one state to redress the injustice allegedly done to the Albanian nation by the Western powers, which left the Albanians scattered through different Balkan countries. Many of these Facebook pages include maps of an imagined “Greater Albania”, which includes territories in what is now Albania, Greece, North Macedonia, Kosovo, Serbia, and Montenegro.[21] The idea of a “Greater Albania” was born 130 years ago and has floated back and forth ever since between the realms of fantasy and political reality, with Albanian politicians from all the region’s Albanian-inhabited areas using this kind of anachronistic nationalism on occasions to consolidate their political power. In terms of societal appeal, the “Greater Albania” project enjoys some support in Kosovo, Albania and North Macedonia. The majority of these pages are created and administered in Albania or Kosovo, or by the Albanian diaspora in Europe and the United States. The high numbers of Albanian followers and commentators from North Macedonia shows the growing appeal of such pages with ethnic Albanians in the country.

In the online space, there are some examples of sites/pages that promote de-radicalisation. There are ethnic Macedonian and ethnic Albanian personalities who promote the peaceful coexistence of all ethnicities and religions as the precondition for the existence of North Macedonia. Their main argument is that all citizens, irrespective of religion or ethnicity, should work together for the prosperity of their children. Some moderate imams who support the view that violence has no place in Islam work in the same direction, seeking to call into question the narratives of radical Islamists. Some Facebook pages has also been created to attack ISIS narratives; one of these hosts a number of videos translated into Albanian.[22]

In the Orthodox Church, Father Pimen is an active Facebook user with over 20,000 followers who presents more progressive ideas and seeks to reconcile modern life with religion.[23] His subtle and often humorous criticism of politicians and their actions frequently puts him in the spotlight. He seems to be patriotic, but pragmatic in his statements. For instance, on the Prespa Agreement, his position was that the agreement was far from ideal, but not as catastrophic as some were describing it and he even took part in the campaign to get people to vote in the referendum. Here is a quote from one of his interviews after a cross was erected in ethnic Macedonian-majority Butel and an Albanian eagle in ethnic Albanian-majority Chair in an attempt to spark ethnic tensions: “We are fed up with patriotic and nationalistic stories and with blood. The fanatic believers who blame the other for their own misery and lack of bread, and are ready to make a show of force and power, to raise their hand against the other, blaming him/them for taking their territory, job or bread, they are a problem.”

One very concerning outcome of the analysis of the online content is that the pages promoting radicalisation are far more numerous than those promoting de-radicalisation.[24] The overall impression given by the analysis of the online content is that radical groups are surgically targeting their audiences in line with their objectives and the space in which they operate.

Online community reactions to de(radicalisation) content

Most of the analysed groups and pages seem to act as echo chambers for the content posted on them. The comments usually reflect agreement and further amplify the original messages, sometimes with a level of hate speech and insults that exceeds the original post. There are few attempts to express disagreement or to debate, and when there is it is over specific details rather than the overriding message. Content presenting daily events and politics in a humoristic or satirical manner generally attract more interaction and comments than ideological or history- and remembrance-related posts.

The analysis of the posts used by ethnic nationalist, right-wing and Islamic radical groups also showed that online users react with “desire” and “acceptance”, which is generally expressed through likes, emojis, positive comments, and shares. However, the level of acceptance depends on the content and style of the posts. For example, posts not clearly identifiable as propaganda, videos hosting sermons by well-known imams or nationalist statements that glorify one or the other ethnicity are more popular or persuasive than others. Highly emotional videos associated with songs or quotes from famous personalities enjoy higher levels of acceptance with the online audience, triggering many reactions and much discussion around the topic they touch upon. In some cases, these posts are produced by, or show support for, a violent extremist personality. In the context of North Macedonia, there are many posts that support imprisoned imams. Online users engage positively with these kinds of posts, endorsing the violent extremist personality mentioned and justifying or condoning violence. One example of such posts are the sermons by imprisoned imams like Rexhep Memishi, whom many users consider a hero.[25]

Nationalist posts based on simplistic patterns are typical Facebook content. Posts by ethnic Albanian nationalists expressing the idea of Albanian unification in one state are the most popular among online users.[26] This material is widely followed by Albanians from North Macedonia, Kosovo, South Serbia, and the Albanian diaspora. The commentators are not only supportive of the idea, they also accuse the Albanian political class of not doing enough for the unification of all Albanians. The posts conveying political messages, including accusations levelled against the Albanian political parties for doing nothing to protect the rights of Albanians in North Macedonia are also very popular, triggering a lot of discussion with nationalistic comments. These nationalist messages and sentiments are more evident during electoral campaigns. Among ethnic Macedonian nationalists, the most popular posts are those featuring anti-Albanian, anti-Greek, and anti-Bulgarian rhetoric. The commentators in these posts employ extreme language and hate speech and view opposition to these countries as a sign of genuine patriotism.

The level of rejection for these posts is very low and, in some cases, non-existent.[27] When rejection exists, it is expressed through messages of logical argumentation which openly state that the use of violence is not the solution to any problem. This kind of argumentation, which does not include insulting those who think differently, is well-received by the other commentators. This approach might encourage empathy and understanding between the two sides. In contrast, rejections expressed through insults and irony trigger heated debates which can result in commentators threatening each other and leave little space for rational argumentation.

When it comes to posts with posts that promote positive messages which condemn violence or provide counter-narratives to the extremists’ propaganda, the general perception is that these posts stimulate lower reaction rates than posts, articles or commentaries that purposefully foster extremism.[28] Not only is there less interaction in the posts that promote de-radicalisation, but even when discussion exists, the commentators give the expression that they are not fully convinced by the counter-messages provided.[29] However, this does not mean that posts of this kind are not increasing online users’ resilience to radicalisation and extremist propaganda. On the contrary, our research has revealed that counter-narrative posts have helped online users exposed to extremist messages to become resilient. The low rates of interaction vis-à-vis these posts can be explained as the result of online users seeking to protect their anonymity.

Conclusion

The online space, including the social media, is also seen as a key factor in weakening communities’ resilience to radicalisation. The unregulated online media environment that allows unverified content to be disseminated, including hate speech, is viewed as a key factor in community vulnerability. For extremist groups of all sorts, the internet has become their most important communication, mobilisation, and propaganda tool. Despite the efforts of the competent authorities to have social media pages with extremist content taken offline, the digital recruitment tactics of extremist groups supporting various types of extremism are still visible on several social media platforms. Social media also play an important role in fostering counter-narratives and re-directing users to safer online environments, but their potential does not seem to have fully exploited by the relevant P/CVE actors, who are not well-suited to producing counter-narratives. When it comes to the traditional media, it seems that they do not play a significant role in promoting religiously-inspired radicalisation in North Macedonia. However, patriotic and nationalist journalism is evident in both Albanian- and Macedonian-language media, expressed primarily through pieces which foster ethno-nationalist extremism.

All in all, violent extremism and radicalisation are complex and multi-faceted challenges. As such, their prevention requires a multi-agency mechanism and a well-coordinated response among all the actors involved in the process. Media should be a constituent part of this mechanism, since the potential of a given P/CVE initiative to build resilience against violent extremism would be hampered by a failure to involve this significant element.

Recommendations

This section outlines key recommendations that stem from the findings and the understanding of the problems under investigation reached by the PAVE team through research in the field conducted in the municipalities of Tetovo and Kumanovo in North Macedonia, and the discourse analyses of online content:

- The government of North Macedonia should examine the possibility of making digital literacy part of the school curriculum. Media literacy programmes can enhance students’ critical thinking and awareness of the tactics used in online ideological propaganda and recruitment. Teaching students effective digital citizenship will equip them with the tools they need to confront the challenges posed by extremist propaganda leading to radicalisation and polarisation; this will enhance their resilience to disinformation.

- The National Committee for Countering Violent Extremism and Countering Terrorism should develop an effective counter-messaging strategy, training its local and state-level actors in how to produce persuasive counter-narratives. A cross-departmental entity tasked with coordinating all the actors engaged in the counter-narrative strategy could boost the effectiveness of the government’s strategic communications at countering violent extremist discourse.

- More structured and systematic research based on online content analysis in consultation with tech companies operating in the field is necessary, if a better understand is to be reached of how the online extremist ecosystem functions in North Macedonia. This kind of knowledge will help make the relevant strategy more responsive to the real online threats, guiding the authorities towards the legal and regulatory actions that should be taken.

- Religious communities should play a more active role in P/CVE actions, including enhancing their presence on online platforms on which religious practitioners can spread messages of inter-ethnic unity. The engagement of religious practitioners in raising awareness and dispelling myths and misconceptions about ethno-national and religious radicalisation using technology and the online space is more necessary than ever.

- The government should improve the capacities of community police by organising mixed group training (ethnic Albanians and ethnic Macedonians), particularly in the area of online prevention. Community police officers need more competences to deal with the online space, and especially chat rooms, gaming platforms, and other open and dark online spaces which enable the radicalisation of individuals by extremist groups. The capacities of other frontline practitioners, including teachers, social workers, and psychologists to deal with online extremism should be also enhanced.

- A serious discussion should be embarked upon between the government and the media on reporting extremism as a necessary step towards promoting good media practices. In this context, increasing cooperation between the P/CVE authorities and media should be prioritised, given the influence that media has in shaping public opinion.

The establishment of media standards and guidelines on reporting extremism will help sensationalism and stereotypes to be avoided along with responsibility for specific form of extremism being attributed to specific ethnic groups. This will also create conditions conducive to an accurate and appropriate use of language. This process requires an open dialogue with a wide range of media representatives, media organisations and regulatory authorities. Such guidelines would improve the quality of reporting and prevent violations of journalistic ethics, guaranteeing that professional standards are uphe

[1]Interview with a journalist conducted in Tetovo in July 2021.

[2]Stefanovski, I., Petkovski, L., Nikolovski, P., Lembovska, M., & Mehmeti, A. (2021). “Sell Out, Tune Out, Get Out, or Freak Out? Understanding Corruption, State Capture, Radicalization, Pacification, Resilience, and Emigration in Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia”. Skopje, North Macedonia: EUROTHINK – Center for European Strategies.

[3]Ibid.

[4]News portal article “Maqedonasi ortodoks i konvertuar në musliman, rekrutonte luftëtarëve Shkup, pranga Imamit e 8 të tjerëve”, Shqiptarja.com, August 2015.

[5]See the Being Macedonian Blog here: http://ednimakedonci.blogspot.com/2013/03/blog-post.html

[6]Interview with a security expert conducted in Kumanovo in July 2021.

[7]See the description of the project “Building resilience against violent extremism and terrorism through Reinforced Journalists, Media and Government Officials” on the official website of the Citizens’ Association Initiative for European Perspective (IEP).

[8] Interview with members of civil society, conducted in Tetovo and Kumanovo in July 2021.

[9] Conclusion from the 4 focus groups discussions conducted in Tetovo and Kumanovo in July 2021.

[10] Conclusion from the discourse analysis of the online content.

[11]Conclusion from the discourse analyses of the online content.

[12]In the video “Mesazh për gurbetqarët – Hoxhë Sadullah Bajrami” hosted on Facebook, the Albanian Imam from Kumanovo is trying to mobilize the Albanian diaspora.

[13]The Facebook pages “Куран и Суннет”, “Аллах е Еден” and “Islamska Mladina” host fundamentalist, anti-West, anti-Shia and anti-Semitic content as well as the preachings of fundamentalist Imams who advocates the extensive covering up of women.

[14]Interview with a civil society representative conducted in Tetovo in July 2021.

[15]The Facebook groups “Помирување” and “Патриотски Македонски Форум” are excellent examples of how these groups spread their messages with a view to influencing Macedonians.

[16]Conclusion from the discourse analysis of the online content in the Macedonian language.

[17]See: https://religija.mk/timotej-izjavata-na-agatangel-e-lichen-stav-mpc-ne-se-mesha-vo-politika/

[18]See: https://arhiva.republika.mk/720562

[19]See: https://www.facebook.com/ivicatodor; https://kurir.mk/makedonija/vesti/otec-ivica-todorov-shto-kje-se-sluchi-ako-se-izleze-da-se-glasa-a-shto-ako-se-bojkotira/

[20]Conclusion from the discourse analyses of the online content.

[21]The Facebook pages “Shqiperia Ilirian Bashkuar”, “Shqiperi Etnike” and “Unioni gjithëshqiptar “Vëllazërimi ynë” host content which promotes the creation of “Greater Albania”.

[22]The Facebook page “Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narratives Videos – Albanian” hosts a number of videos translated into Albanian with a view to challenging ISIS narratives.

[23]See:https://www.facebook.com/profile.php?id=100009523291868; https://iportal.mk/makedonija/otec-pimen-dogovorot-za-imeto-ne-e-idealen-no-ne-e-nitu-neshto-pogubno/

[24]Conclusion from the discourse analysis of the online content.

[25]The uploader of this video “Obligim shfaqja e fes – Hoxhë Rexhep Memishi” is a passionate supporter of the Imam, and asks Allah to release him from prison. This post has 215 likes, 34 shares and 4 comments, all of which are supportive of the Imam.

[26]The post “Bashkohu Shqiperi. Te gjeth per nje shqiperi etnike” is typical of material posted by Albanian ethnic nationalists. This specific post has 114 likes, 11 shares and 6 comments, all of which are supportive of the idea of a “Greater Albania”.

[27]Conclusion from the discourse analysis of the online content.

[28]The Facebook video “Duke u Bërë Zbulues për Kalifatin e Shtetit Islamik” provides a counter-message to the narratives of ISIS but has only 16 views and no comments.

[29] Conclusion from the discourse analyses of the online content.