- The diplomatic relations between South Africa and the European Union have been robust, and they were solidified by the negotiation of the South Africa-EU Trade and Development Cooperation Agreement (TDCA) in 1999.

- The EU has become South Africa’s largest trading partner and largest development partner and remains the EU’s largest trading partner in Africa. South Africa holds significance as a valuable ally to the European Union due to its recognized role as a regional leader and its involvement in prominent international organizations such as the BRICS, the AU, the WTO, UN and the G20.

- Past developments led to strain in this strategic relationship, as was seen by the emergence of disagreements over the provisions of the Southern African Development Community Economic Partnership Agreement (SADC EPA) as well as South Africa’s decision to abrogate bilateral investment treaties with certain EU member states.

- Present tensions revolve around recent developments in the Indo-Pacific, EU’s decision to impose new imposed regulations on citrus exports as well as South Africa’s stance towards the Ukrainian war.

- An emerging area for South Africa is the environment and the impact of climate change on its long-term national interest. Creating jobs and offering income opportunities through a green transition while assisting those who will lose from shifts in the economy is crucial for any policy success between the two actors.

- The Global Gateway initiative, part of the EU’s digital external action strategy, aims to promote global connectivity and infrastructure while advancing democratic values and sustainability. The EU pledged to invest €150 billion in Africa as part of the GG, with South Africa as an example of a partner.

- It is imperative that the European Union (EU) maintain its positioning as a compelling and indispensable partner for South Africa. Concerted efforts should be made by both parties to increase bilateral negotiations on the matter of Citrus Import regulations that balance both the regulatory concerns of the EU and the trade interests of South Africa.

- The EU has already found success in terms of environmental cooperation considering that it is a pivotal partner in assisting South Africa’s transition to a green economy. The area of renewable energy should therefore remain at the forefront of collaboration efforts.

- The EU must offer a convincing narrative for its digital cooperation that considers the needs of its partner countries. Investments in cutting-edge digital technology are necessary for this.

- The EU should engage in constructive dialogue that continually seeks to identify areas of mutual interest and benefits for both actors along shared values.

Read here in pdf the Joint Policy Paper by the University of Pretoria and ELIAMEP written by: Aphroditi Sentoukidi, Research Intern, Hellenic Foundation for European & Foreign Policy; Daniela Marggraff, Researcher, University of Pretoria; Pavlos Petidis, Junior Research Fellow, Hellenic Foundation for European & Foreign Policy and Tshegofatso Johanna Ramachela, Research Associate, University of Pretoria.

Introduction

The establishment of diplomatic relations between South Africa (SA) and the European Union (EU) were solidified in 1999 through the negotiation of the SA-EU Trade and Development Cooperation Agreement (TDCA) (Gladwin & Otto 2010). Since then, the relationship has developed significantly, especially in the economic domain.

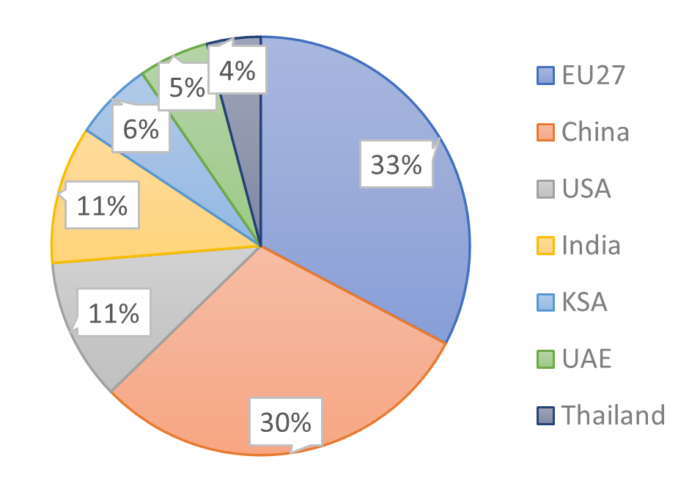

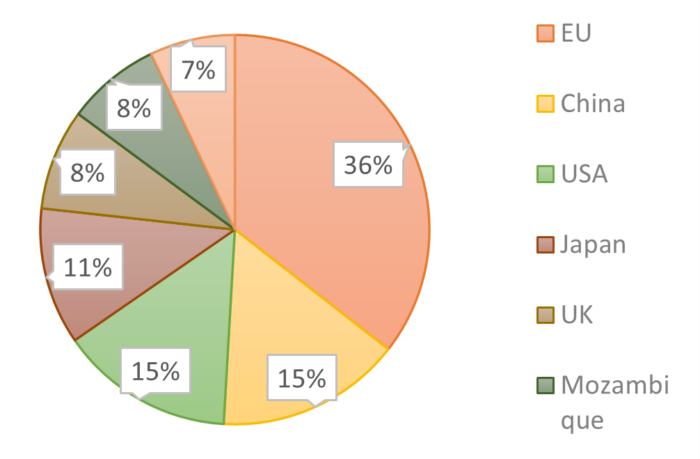

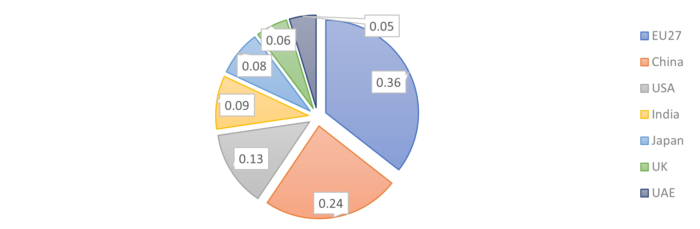

The establishment of diplomatic relations between South Africa (SA) and the European Union (EU) were solidified in 1999 through the negotiation of the SA-EU Trade and Development Cooperation Agreement (TDCA) (Gladwin & Otto 2010). Since then, the relationship has developed significantly, especially in the economic domain. A few facts attest to this: (1) The EU constitutes South Africa’s largest trading partner accounting for 22 percent of South Africa’s total trade in 2021 (PMGa 2022); (2) the EU is South Africa’s largest development partner accounting for 70 percent of the country’s official development assistance; and (3) South Africa is the only African country that has a strategic partnership with the EU and remains the EU’s largest trading partner in Africa (for more on statistics regarding SA-EU trade, see Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3, below) (European Union External Action 2023; Kell & Vines 2021).

Figure 1. South Africa imports – Top Trading Partners 2022 (based on Eurostat data

Figure 2. South Africa exports – Top Trading Partners 2022 (based on Eurostat data)

Figure 3. South Africa total trade – Top Trading Partners 2022 (based on Eurostat data)

However, after 2006, there was a noticeable decline in sentiments, and the relationship arguably hit an impasse between 2013 and 2018. This could perhaps be attributed to the shift away from South Africa’s role as a ‘bridge-builder’ between the North and the South, which was especially apparent during Thabo Mbeki’s second term (2004-2008) (Sidiropoulos 2008: 110) or South Africa’s decision to join the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) which is often viewed as being anti-Western (Hendricks & Majozi 2021: 67). While South Africa’s foreign policy appeared to be undergoing changes, the EU was simultaneously working to clarify its position on the global stage and resolve internal problems. For example, during the 2012 and 2013 SA-EU Summits, the EU was experiencing difficulties with its integration agenda. The 2008 financial crisis brought about a deeper resentment from countries hit hardest by austerity measures (Helly 2012). The steady stream of refugees escalated in 2015 with calls for the reintroduction of internal EU borders and border closures (Grimm & Hackenesh 2017). These problems developed into a multi-dimensional crisis in Europe when the United Kingdom (UK) notified the EU of its intention to leave the union after a national referendum won by the Brexit camp (Soko & Qobo 2017).

As both parties struggled with internal and international concerns that could not always be resolved inside the SA-EU partnership, the desire for participation arguably decreased. However, after taking over from former president Jacob Zuma, South Africa’s current president, Cyril Ramaphosa regained contact with previous partners in Europe to get international investors and development partners to return to the country.

Such developments posed challenges at all levels of the SA-EU partnership. As both parties struggled with internal and international concerns that could not always be resolved inside the SA-EU partnership, the desire for participation arguably decreased. However, after taking over from former president Jacob Zuma, South Africa’s current president, Cyril Ramaphosa regained contact with previous partners in Europe to get international investors and development partners to return to the country. (Bertelesmann-Scott 2021: 252). After the 2018 SA-EU Summit, President Ramaphosa emphasised the importance of the strategic relationship and the need to “renew and deepen” cooperation at the “bilateral, regional and global level” (The South African Government 15 November 2018). Within this context, this policy brief aims to analyse where the EU fits into the foreign policy of South Africa and vice versa by focusing on two specific elements of the partnership, namely climate change and digital cooperation. In doing so, this brief also considers both past and contemporary tensions that have jeopardised the current SA-EU partnership. Taking into consideration the fact that South Africa tends to, or may in the future, strive to diversify its trading partners, one of the main recommendations this brief makes is that the SA-EU partnership needs to grow beyond the mere trade-transactional approach and rather embrace other areas of cooperation such as in the environmental and digital domain.

Strategic understandings of the partnership

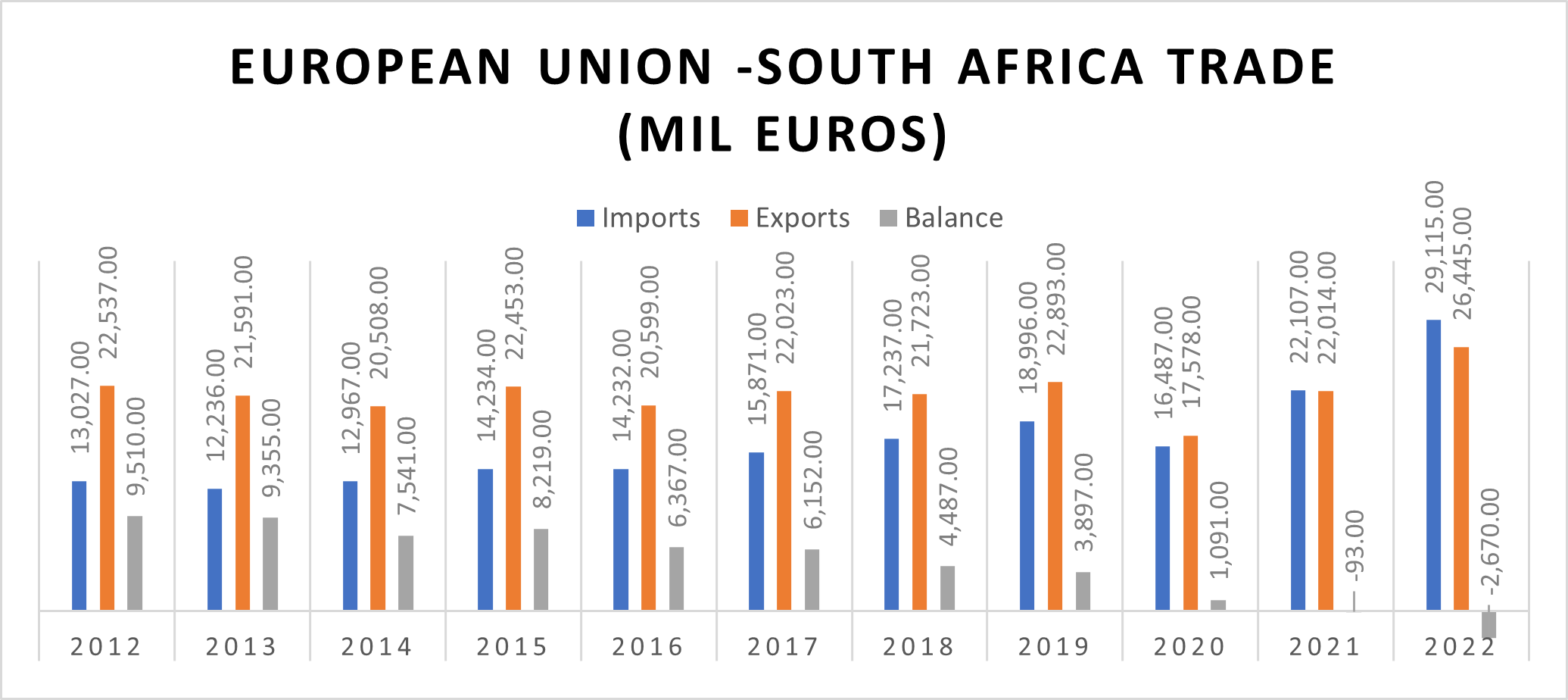

According to the head of trade at the EU embassy in Pretoria, South Africa’s exports to the EU increased by 30 percent in 2021, and this was the first time since 2004 that South Africa recorded a trade surplus. It must also be noted that more value-added goods were directed to the EU markets from South Africa in comparison to other areas of the world.

In the beginning of 2023, the EU’s High Representative Josep Borrell asserted that trade relations between the EU and South Africa are following a positive trajectory (for more, see Figure 4 below). Over recent years the export mix from South Africa to the EU has become more diverse, including manufactured products and not only primary commodities (European Commission n.d.). The economic partnership between the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and the EU – known as the Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) – has contributed to this. Under this agreement, the EU grants preferential access to 98.7 percent of South African goods (Tralac 2022). Although it is a reciprocal trade agreement, meaning both the EU and the SADC group offer preferential market access to each other, the agreement has a particular advantage for African states, because the EU provides greater preferential and duty-free access, while the SADC group are permitted to keep tariffs on sensitive sectors. According to the head of trade at the EU embassy in Pretoria, South Africa’s exports to the EU increased by 30 percent in 2021, and this was the first time since 2004 that South Africa recorded a trade surplus (SADC-EU EPA Outreach South Africa n.d.). It must also be noted that more value-added goods were directed to the EU markets from South Africa in comparison to other areas of the world. Along with this, the EU is responsible for the biggest foreign direct investment (FDI) in South Africa – in 2020, the EU accounted for 40.3 percent of all FDI. Investments focused on advanced manufacturing and vehicles and services, which is important as it rejects the perception that EU investment is in mining and raw materials (Daily Maverick 2022).

Figure 4. EU-South Africa Trade (based on Eurostat data)

South Africa pursues the advancement of the African Agenda, promotes multilateralism, and champions the rules-based international system, particularly the reform of global political and economic governance.

While South Africa has iterated the importance of the EU as a partner in its 2011 Foreign Policy White Paper titled “Building a Better World: The Diplomacy of Ubuntu”, in its recent “Framework on South Africa’s National Interest and its Advancement in a Global Environment” (hereafter, National Interest document) (2022), less attention has been paid to the EU. South Africa’s engagement in the international arena is described as based on the principles of Pan-Africanism and South-South solidarity, where “Africa remains at the centre of [its] foreign policy” (Ramaphosa 20 August 2023). South Africa pursues the advancement of the African Agenda, promotes multilateralism, and champions the rules-based international system, particularly the reform of global political and economic governance (DIRCO 2022: 8-14). For example, South African President Ramaphosa explains that there needs to be reform of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to ensure that “African countries and other countries of the Global South are properly represented and that their interests are effectively advanced” (South African Government 9 March 2023), while South Africa’s Minister of International Relations and Cooperation, Naledi Pandor has stated that South Africa looks forward “to working closely with new non-permanent members of the Security Council to urge them to initiate a genuine robust process of reform” (PMGb 2022). South Africa has received support from EU member states, most notable Germany, with the German Foreign Minister expressing support for two permanent seats for Africa at the UNSC (VOA 13 January 2023). While Africa and countries in the Global South occupy a central position in South Africa’s foreign policy, the National interest nonetheless iterates that the country is also willing to work with countries of the North “to develop a true and effective partnership for a better world” (DIRCO 2022: 8).

As mentioned above, the EU has designated South Africa as a significant actor within Southern Africa on matters related to regional integration. A primary objective of the EU’s SPs is to concentrate on methods by which these strategic partners can unlock or support greater regional integration.

In 2006, South Africa became an EU strategic partner. A fundamental tenet of the Strategic Partnership’s (SP) founding document, which served as its cornerstone, was the acknowledgment of South Africa’s progressive constitution (Masters 2014a). This group of ideas encompassed more fundamental concepts shared by both areas, including the promotion of human rights, democracy, the rule of law, and sustainable development (Bertelesmann-Scott 2021). In terms of many shared ideals and ideas during the 1990s, South Africa and the EU established a robust connection. Cooperation already existed in the areas of economic development, research, and technology, as well as trade and investment (Masters 2014b). The Mgobagoba Dialogue or Action Plan foresaw the development of novel avenues of cooperation in the areas of environmental cooperation and climate change, sharing of experiences on EU Regional Policy, ICT, employment and social affairs, criminal justice, macroeconomic dialogue, education and training, cultural cooperation, and sport and recreation (Landsberg & Hierro 2017). The EU’s official remarks encouraged these broad assessments of the EU. South Africa has witnessed substantial benefits since the SP’s inception, such as the introduction of the Infrastructure Investment Programme for South Africa (worth €1 million), which is being used to clear backlogs in infrastructure both in South Africa and throughout the region (Mthembu 2017). As mentioned above, the EU has designated South Africa as a significant actor within Southern Africa on matters related to regional integration. A primary objective of the EU’s SPs is to concentrate on methods by which these strategic partners can unlock or support greater regional integration (Bertelesmann-Scott 2021).

In addition, South Africa holds significance as a valuable ally to the European Union due to its recognized role as a regional leader and its involvement in prominent international organizations such as the BRICS (Brazil, Russian, India, China, South Africa), the African Union (AU), the WTO (World Trade Organisation), UN (United Nations) and the G20 (Group of 20).

In addition, South Africa holds significance as a valuable ally to the European Union due to its recognized role as a regional leader and its involvement in prominent international organizations such as the BRICS (Brazil, Russian, India, China, South Africa), the African Union (AU), the WTO (World Trade Organisation), UN (United Nations) and the G20 (Group of 20). Furthermore, its serves as a strategic entry point to access the African continent (Fioramonti & Kotsiopoulos 2015: 2). The Joint Africa EU Strategic Partnership and the EU’s continental approach to Africa, which were both introduced concurrently with the 2007 Lisbon Declaration, must also be considered from the standpoint of the EU[1]. As explained in the Multi-Annual Indicative Programme 2021-2027 document, South Africa is a key partner to promote and streamline competition policy on the continent at the national, regional, and continental level (potentially through the AfCFTA Competition Protocol), thereby improving investment conditions for African and EU investors alike (European Commission 2021b). South Africa does not only offer the EU a potential inroad into the continent in terms of intra-regional relationships, but the influence it has in the various multilateral institutions means that it can play an important role in influencing the policies and agendas of other states (Landsberg & Hierro 2017). At a 2016 workshop, the then Head of the EU delegation to South Africa pointed out that “countries like South Africa are key in building bridges between various groups and organizations” (Masters & Hierro 2016: 8). In this sense, South Africa holds a vital role to the EU, not only in terms of economics, such as the value of trade but also in terms of propagating norms and values that the EU espouses.

Past tensions

Tensions also arose when the South African government decided to no longer renew the bilateral investment treaties (BITs) with the EU in 2012, arguing that they were outdated and skewed in favour of foreign investors.

With the aim of enhancing its trade opportunities in EU markets, South Africa became a participant in the SADC EPA negotiations in 2016. This decision was made in order to synchronize the TDCA with the potential EPA agreement. Unfortunately, the European Commission denied South African exporters preferential access to EU markets for their agricultural products and instead pushed for mutual recognition and protection of geographical indications (Soko & Qobo 2017). However, the final agreement included some notable concessions. Complete exemption from import duties would be granted for a range of products originating from Botswana, Lesotho, Mozambique, and Swaziland. A significant proportion, specifically 98.7 percent, of the imported commodities originating from South Africa would experience a positive impact through the reduction of tariffs. SADC members were permitted to use imported inputs in the clothing and textile products, deploy import taxes or safeguards in the event of an EU import surge, particularly affecting sensitive goods. Tensions also arose when the South African government decided to no longer renew the bilateral investment treaties (BITs) with the EU in 2012, arguing that they were outdated and skewed in favour of foreign investors (News24 28 September 2018). Even further back, at the 2013 summit between the EU and South Africa, the EU’s trade commissioner Karel de Gucht expressed the EU’s displeasure about not being considered in a collaboration intended to be strategic. Of greater significance, the voiding of the BITs sparked fears that European investors would not be sufficiently protected and that investment costs would rise. Despite this, the political climate between the two countries significantly softened in the years after. President Zuma explicitly mentioned the EU’s contribution to job creation in his 2016 State of the Nation address which was perceived as a “nod to the EU” (Soko & Qobo 2017).

Contemporary challenges in the partnership

New citrus importation measures

While there have been high-level engagements between South Africa and the EU, the EU still upholds the export restrictions, which has led Agricultural Minister Thoko Didiza to suggest that the country’s exporters might look elsewhere for markets. More recently, South African farmers have now called upon their government to lodge a complaint against the EU at the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

One of the major contemporary challenges that have impacted relations between the EU and South Africa are the rules imposed by the EU regarding the importing of Citrus, which may lead to losses of R500 million for South Africa (FoodforMzanzi 20 April 2023). The EU imposed new regulations in June of 2022 concerning the False Coddling Moth (FCM) and Citrus Black Spot (CBS), which the Citrus Growers Association (CGA) of South Africa has labelled as having no scientific basis and rather aimed at disrupting the South African Citrus industry (Cape Talk 28 June 2023). According to these regulations, exporters will need to expose their fruit to special cooling treatments, which the CEO of the CGA, explains imposes an “estimated $75 million investment in new technology and storage on citrus growers” (Africa News 28 June 2023). In response to the new regulations, President Ramaphosa posited that he was “disappointed at the (EU’s) acts of protectionism against South Africa’s agricultural products” (News24 2023). While there have been high-level engagements between South Africa and the EU, the EU still upholds the export restrictions, which has led Agricultural Minister Thoko Didiza to suggest that the country’s exporters might look elsewhere for markets. More recently, South African farmers have now called upon their government to lodge a complaint against the EU at the World Trade Organisation (WTO) (Reuters 2023).

South Africa’s stance on the Russia-Ukraine conflict

In keeping with this articulation, South Africa was part of a six-member African delegation that conducted peace talks with both Russia and Ukraine (Imray, 2023). Despite South Africa’s stance of non-alignment, some events have called this into question. For example, from 17 to 27 February 2023, South Africa hosted naval exercises with China and Russia (‘Operation Mosi’), elicited criticism by Western officials and media, citing the ‘inappropriate timing’ of the drills, as they coincided with the start of the Russia-Ukraine conflict (Smith 2023).

In addition, South Africa’s official stance of non-alignment on the Ukrainian conflict has come under intense scrutiny (Mohammed 2023) and criticized as being damaging to its partnership with the EU (Mathekga 2022). During a visit to South Africa in 2023, Josep Borrell urged Pretoria to use its ties to convince Moscow to end the conflict (Bartlett 2023) while South Africa’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, Naledi Pandor, posited that the only path to settle international disputes is through diplomacy, dialogue, and a commitment to the principles of the United Nations Charter (Mohammed 2023; EEAS 2023a). In keeping with this articulation, South Africa was part of a six-member African delegation that conducted peace talks with both Russia and Ukraine (Imray, 2023). Despite South Africa’s stance of non-alignment, some events have called this into question. For example, from 17 to 27 February 2023, South Africa hosted naval exercises with China and Russia (‘Operation Mosi’), elicited criticism by Western officials and media, citing the ‘inappropriate timing’ of the drills, as they coincided with the start of the Russia-Ukraine conflict (Smith 2023). In response to this, Minister Pandor stated that “all countries conduct military exercises with friends worldwide”, adding “there should be no compulsion on any country that it should conduct them with any other partners”. Within this context, it must be noted that while both South Africa and the EU seem to share values such as advancing human rights, democracy, and the rule of law, it appears in practice South Africa and the EU do not always see eye-to-eye. To some, the case of the Russian-Ukraine conflict and South Africa’s stance has called into question South Africa’s commitment to human rights as enshrined in the Constitution.

Developments in the Indo-Pacific

Furthermore, another source of tension is China’s growing influence in the Indo-Pacific. As argued by Fabricius (2022), South Africa is “suspicious” of the concept ‘Indo-Pacific’ because it “fears being dragged into big power rivalries”. At the first Indo-Pacific Forum in France in 2022, South Africa declined an invitation to attend because Pretoria concluded that the event was anti-China. On 13 May 2023, the second EU Indo-Pacific Ministerial Forum was held in Sweden, where despite being on the discussion agenda, China was not invited (Bermingham 2023). South Africa did not attend. Albeit China’s non-recognition of the Indo-Pacific concept, South Africa takes pride in endorsing the long-awaited Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) Outlook on the Indo-Pacific. Many EU member states and the EU as a collective body have also developed Indo-Pacific strategies where a strategic approach towards Africa, specifically through regional organizations, is reflected but little agency to Africa actors is conceded (Mattheis & Diaz 2022: 46).

From the title of a recently published article in The Economist (2023), it is evident that there is a perception that South Africa is “drifting into the Sino-Russia orbit’, ignoring the existence of long-established relations with both China and Russia (DIRCO 2023). There is a sense that Europe’s issues and interests are prioritised above those of the Global South, especially where Africa is concerned. This serves to undermine the South Africa-EU partnership, because South Africa views its interests as inseparable from those of Africa.

From the title of a recently published article in The Economist (2023), it is evident that there is a perception that South Africa is “drifting into the Sino-Russia orbit’, ignoring the existence of long-established relations with both China and Russia (DIRCO 2023). There is a sense that Europe’s issues and interests are prioritised above those of the Global South, especially where Africa is concerned. This serves to undermine the South Africa-EU partnership, because South Africa views its interests as inseparable from those of Africa. Of notable significance is South Africa’s commitment and loyalty to its partners which provided support (training, arms, refuge) during the anti-Apartheid liberation struggle. In response to this sentiment, Borrell maintains that the EU is not attempting to deprive South Africa of the policy options of diplomacy – rather every country has the right to have its own foreign policy according to its own interests.

Where to from here? Specific areas for cooperation: environmental cooperation and digital revolution

Environmental Cooperation

Considering that one of the major challenges repeatedly identified in South Africa’s white papers is the triple challenge of “inequality, unemployment and poverty” the JETP is especially significant as it aims to accelerate the decarbonisation of South Africa’s economy “by assisting in the financing of grants, loans and investments and to ensure that vulnerable communities (such as coal miners) are not negatively impacted and left behind”.

An emerging issue area for South Africa is the environment and the impact of climate change on its long-term national interest (DIRCO 2022: 11). While the country reduces its reliance on certain fossil fuels, care needs to be taken to ensure that sustainable alternative jobs are created (European Commission 2021). Some have argued that efforts to address this threat have been compounded by a “lack of a common approach at a global level” (DIRCO 2022: 26). However, progress has been made recently, with the launching of the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) between the governments of South Africa, the EU, and other countries such as France, the UK, the US, and Germany in November 2022. Considering that one of the major challenges repeatedly identified in South Africa’s white papers is the triple challenge of “inequality, unemployment and poverty” the JETP is especially significant as it aims to accelerate the decarbonisation of South Africa’s economy “by assisting in the financing of grants, loans and investments and to ensure that vulnerable communities (such as coal miners) are not negatively impacted and left behind’” (European Commission 2021a). However, obstacles have already emerged as President Ramaphosa has stated that owing to South Africa’s current energy security crisis, South Africa may delay closing coal stations (Climate Home News 2023). European countries behind the JTEP have expressed that they understand that short-term measures may need to be introduced to address the current emergency but that this should not lead to back-sliding on the transition (Climate Home News 2023).

South Africa needs a partner that is sensitive to South Africa’s development needs. The EU has the potential to position itself as a reliable partner in this regard. The EU as a diplomatic actor is commonly conceptualized as having a distinctive position in global climate politics, functioning as both a leader and mediator, often referred to as a ‘leadiator’ (Blaschke et al. 2021, Backstrand & Elgström 2013). Therefore, the EU adopts a proactive strategy, considering the international context. There is a strong focus placed on the development of bridges to foster unity and establish international coalitions. Chevallier and Benkenstein (2021) for instance, argue that a thorough examination of the EU’s Comprehensive Strategy for Africa, which was introduced in March 2020, reveals the importance of leadership and commanding influence in promoting the green transition. Additionally, they propose examining novel avenues for trilateral collaboration on climate and energy matter between South Africa, the African Union, and the EU.” Overcoming the stark socioeconomic frictions within South Africa will remain a key element for successful cooperation. All policy actions have to relate to and serve this function. Creating jobs and offering income opportunities through a green transition while assisting those who will lose from shifts in the economy is crucial for any policy success. Staying with the ecological boundaries of the planet requires socio-economic sustainability and convincing a sometimes-sceptical public to gain support in an electoral democracy; South Africa is a clear reminder of this universal logic.

An enhanced digital partnership

During the summit between the EU and the African Union in February 2022, the EU introduced a number of trustworthy investment initiatives for Africa as part of the GG. The EU made a commitment to allocate €150 billion in investments by the year 2027. In that context, South Africa constitutes an example of an African partner that has made important steps in forging a strong digital footprint.

Another sphere of collaboration lies inside the realm of digital technology. The Global Gateway (GG) initiative holds particular relevance in this context, as it was established within the framework of a developing European strategy for digital external action. The EU has introduced this strategic plan aiming at positioning itself competitively in the worldwide arena of connectivity and infrastructure. In addition, it seeks to uphold democratic principles and sustainability while addressing the existing investment deficit in global infrastructure. Furthermore, it aims to accelerate sustainable growth and facilitate the global recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. During the summit between the EU and the African Union in February 2022, the EU introduced a number of trustworthy investment initiatives for Africa as part of the GG. The EU made a commitment to allocate €150 billion in investments by the year 2027. In that context, South Africa constitutes an example of an African partner that has made important steps in forging a strong digital footprint. The unveiling of the National Development Plan (NDP) in South Africa envisioned the creation of a comprehensive and inclusive information infrastructure that would be readily available and accessible to all. This infrastructure was intended to cater to the needs of citizens, businesses, and the public sector, while also fostering effective economic and social engagement. The target for achieving this vision was set for the year 2030 (Abrahams et al. 2022). Under the 2017 National e-Strategy, the country has developed thematic policy frameworks. Examples include the National and Future Digital Skills Strategy of 2020 to develop the digital skills ecosystem (Abrahams et al. 2021). South Africa, along with Kenya, Senegal and Ghana, are among the African countries driving digital change in their various regions. However, a lot of technological progress has not been inclusive. Currently, they are all infusing digital policy into various fields while concentrating on boosting connectivity, raising everyone’s level of digital literacy, and fostering an environment where the private sector can lead in digital innovation. Thus, the emerging European perspective to the digital part of GG, with its holistic approach, has the potential to be beneficial (Teevan & Domingo 2022).

Concluding remarks and recommendations

On paper, the EU seemingly features less in the foreign policy of South Africa than in earlier years. Although it may be too early to jump to any conclusions about the trajectory of the SA-EU partnership based on this, it is vital that the EU continues to position itself as an attractive and needed partner to South Africa. This is especially the case since South Africa has started to turn to other actors, particularly in the Global South to further achieve the goals it sets out in its foreign policy.

On paper, the EU seemingly features less in the foreign policy of South Africa than in earlier years. Although it may be too early to jump to any conclusions about the trajectory of the SA-EU partnership based on this, it is vital that the EU continues to position itself as an attractive and needed partner to South Africa. This is especially the case since South Africa has started to turn to other actors, particularly in the Global South to further achieve the goals it sets out in its foreign policy. Considering this, there are several key recommendations that this brief makes:

- One area in which the EU can carve a niche role for itself is in terms of environmental cooperation. The EU has already found success in terms of environmental cooperation considering that it is a pivotal partner in assisting South Africa’s transition to a green economy. The area of renewable energy should therefore remain at the forefront of collaboration efforts.

- While the EU continues to be an important trade partner to South Africa, the partnership is currently strained, in part due to the Citrus Import regulations. It is vital that a meaningful solution is found to avoid compromising the relations any further. Concerted efforts should be made by both parties to increase bilateral negotiations on the matter of Citrus Import regulations that balance both the regulatory concerns of the EU and the trade interests of South Africa. Furthermore, to address the concerns of the EU, increased industry collaboration (which includes knowledge-sharing and technology transfer) could be considered.

- The EU must offer a convincing narrative for its digital cooperation that considers the needs of its partner countries. Investments in cutting-edge digital technology are necessary for this, as are joint research projects with African countries and the development of regulations to include African economies into its digital value chains.

- On the matter of South Africa diversifying its trade relations, which is especially pertinent with South Africa chairing the BRICS, the EU should engage in constructive dialogue that continually seeks to identify areas of mutual interest and benefits for both actors along shared values.

Bibliography

Abrahams, L., Ajam, T., Al-Ani, A. and Hartzenberg, T. 2022. Crafting the South African Digital Economy and Society: MultiDimensional Roles of the Future-Oriented State. A Conceptual Framework and Selected Case Analyses. LINK Public Policy Series. Johannesburg: Learning Information Networking Knowledge (LINK) Centre, University of the Witwatersrand.

Africa News. 2023. Unfair EU rules to hit SA orange exports, say growers. Internet: https://www.africanews.com/2023/06/28/unfair-eu-rules-to-hit-sa-orange-exports-say-growers//. Access: 7 August 2023.

Bäckstrand K. & Elgström O. 2013. The EU’s role in climate change negotiations: from leader to ‘leadiator’, Journal of European Public Policy, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2013.781781

Bartlett, K. 2023. EU’S Borrell urges South Africa to get Russia to end the Ukraine war. Voice of America. Internet: https://www.voanews.com/a/eu-s-borrell-urges-south-africa-to-get-russia-to-end-ukraine-war-/6936839.html. Access; 8 May 2023.

Bermingham, F. 2023. China not invited to EU, Indo-Pacific policy talks in Sweden – but it will loom over them. South China Morning Post. Internet: https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3220242/china-not-invited-eu-indo-pacific-policy-talks-sweden-it-will-loom-over-them. Access: 14 May 2023.

Bertelesmann-Scott, T. 2021. The European Union-South Africa Strategic Partnership: Aligning Interests in a Multi-Layered Environment in: The European Union’s Strategic Partnerships Global Diplomacy in a Contested World (eds.) Laura C. Ferreira-Pereira Michael Smith, pp.245-265. Palgrave Macmillan.

Blaschke, C. John, D. W, J. 2021. The EU as a global leader on climate action between ambition and reality. Hans Seidel Stiftung.

Cape Talk. 2023. 80 000 tons of oranges might not make it to European supermarket shelves because of the new EU regulations, warns the Citrus Growers’ Association. Internet: https://www.capetalk.co.za/articles/477594/new-eu-pest-measures-threaten-citrus-industry-and-are-really-protectionism. Access: 7 August 2023.

Chevalier, R. & Benkenstein, A. 2021. Exploring South African “Green Leadership” in the Context of the European Green Deal. South African Institute of International Affairs.

Climate Home News. 2023. Rich nations “understanding” of South African delay to coal plant closures. Internet: https://www.climatechangenews.com/2023/05/22/rich-nations-understanding-of-south-african-delay-to-coal-plant-closures/. Access: 25 May 2023.

Daily Maverick. 2022. SA companies could boost exports to EU by R350bn a year, research shows. Internet: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2022-05-30-sa-companies-could-boost-exports-to-eu-by-r350bn-a-year-research-shows/. Access: 14 May 2023.

Delegation of the European Union to Botswana and SADC. N.d. The European Union’s Cooperation with the Southern African Development Community. Internet: https://www.sadc.int/fr/file/3223/download?token=GCRQ7GU1. Access: 15 May 2023.

Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO). 2011. White Paper on South African Foreign Policy: Building a Better World – The Diplomacy of Ubuntu. Pretoria: Government Printer.

Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO). 2022. Framework Document on SOUTH AFRICA’S NATIONAL INTEREST and its advancement in a Global Environment. Pretoria: Government Printer.

Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO). 2022. Speech by the Minister of International Relations and Cooperation, Dr Naledi Pandor, on the occasion of the Budget Vote, 12 May 2022. Internet: https://www.dirco.gov.za/blog/2022/05/12/speech-by-the-minister-of-international-relations-and-cooperation-dr-naledi-pandor-on-the-occasion-of-the-budget-vote-12-may-2022/. Access: 15 May 2023.

Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO). 2023. Media Statement: South Africa and the People’s Republic of China commemorate 25 years of Diplomatic Relations, 1 January 2023. Internet: https://www.dirco.gov.za/blog/2023/01/01/south-africa-and-the-peoples-republic-of-china-commemorate-25-years-of-diplomatic-relations/. Access: 9 May 2023.

- 2011. Agenda for Change. Internet: https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/publication/agenda-change-com2011-637-final_en#:~:text=The%20Agenda%20for%20Change%2C%20adopted,is%20delivered%20have%20been%20introduced. Access: 15 May 2023.

- 2021a. France, Germany, UK, US and EU launch ground-breaking International Just Energy Transition Partnership with South Africa. Internet: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/cs/ip_21_5768. Access: 15 May 2023.

- 2021b. Republic of South Africa: Multi-Annual Indicative Programme 2021 – 2027. Internet: https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-01/mip-2021-c2021-9112-south-africa-annex_en.pdf. Access: 14 May 2023.

European Commission. N.d. South Africa EU trade relations with South Africa. Facts, figures and latest developments. Internet: https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/south-africa_en. Access: 15 May 2023.

European External Action Service Press Team. 2023. South Africa: Joint press conference by High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell and Minister for International Relations and Cooperation Naledi Pandor. EEAS. Internet: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/south-africa-joint-press-conference-high-representativevice-president-josep-borrell-and_en. Access: 8 May 2023.

European External Action Service Press Team. 2023. The war on Ukraine, partnerships, non-alignment and international law. EEAS. Internet: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/war-ukraine-partnerships-non-alignment-and-international-law_en. Access: 9 May 2023.

European Union External Action. 2016. Shared Vision, Common Action: A Stronger Europe. Internet: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/eugs_review_web_0.pdf. Access: 15 May 2023.

European Union External Action. 2021. Human Rights & Democracy. Internet: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/human-rights-democracy_en. Access: 15 May 2023.

European Union External Action. 2023. A Strategic Compass for Security and Defence. Internet: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/strategic_compass_en3_web.pdf. Access: 15 May 2023.

EEAS. 2023. South Africa: Joint press conference by High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell and Minister for International Relations and Cooperation Naledi Pandor. Internet: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/south-africa-joint-press-conference-high-representativevice-president-josep-borrell-and_en. Access: 14 May 2023Fabricius, P. 2022. Africa a low presence in the first Indo-Pacific forum. Institute for Security Studies. Internet: https://issafrica.org/iss-today/africa-a-low-presence-in-the-first-indo-pacific-forum. Access: 10 May 2023.

Fioramonti, L. & Kotsopoulos, J. 2015. The evolution of EU–South Africa relations: What influence on Africa? South African Journal of International Affairs, 22(4): 463-478.

FoodforMzanzi. 2023. EU not budging on citrus exports – Didiza. Internet: https://www.foodformzansi.co.za/eu-not-budging-on-citrus-exports-didiza/. Access: 25 May 2023.

Geddie, E. 2023. EU needs to understand the realities in the West Bank. Politico. Internet: https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-west-bank-israel-palestine-conflict-attacks-apartheid/. Access: 5 May 2023

Gladwin C. & Otto, R.J. 2010. South Africa-European Union Trade Relations: The Trade, Development and Cooperation Agreement – Opportunities and Challenges and Implications for Trade Policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/03031853.1999.9524890

Government of South Africa. 2021. Government Gazette Vol. 672, 1 June 2021, No. 44651. Government of South Africa.

Grimm, S. & Hackenesch, C. (2017) The EU–South Africa Strategic Partnership: Waning affection, persisting economic interests, South African Journal of International Affairs, 24:2, 159-174. https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2017.1334585

Imray, G. 2023. Putin, Zelenskyy agree to meet with ‘African leaders peace mission,’ says South Africa president. Internet: https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-peace-africa-putin-zelenskyy-2e082ce281d405d94451cab9dad4212f. Access: 25 May 2023.

Hendricks, C. & Majozi, N. 2021. South Africa’s International Relations: A New Dawn? Journal of Asian and African Studies, 56(1): 64-78.

Helly, D. The EU–South Africa strategic partnership: changing gear?’, Policy Brief 7 of the European Strategic Partnership Observatory, Brussels: Egmont, 2012, http://www.egmontinstitute.be/wpcontent/uploads/2014/01/ESPO-brief-7.pdf

Jurgens, R. 2022. Russia in Ukraine: South Africa’s unprincipled stance. Good Governance Africa. Internet: https://gga.org/russia-in-ukraine-south-africas-unprincipled-stance/. Access: 10 May 2023.

Kell, F. & Vines, A. 2021. The evolution of the Joint Africa- EU Strategy (2007– 2020). In The Routledge Handbook of EU- Africa Relations, edited by T. Haastrup, L. Mah. N. Duggan. London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Landsberg, C. & Hierro, L. (2017) An overview of the EU–SA Strategic Partnership 10 years on: Diverging world views, persisting interests, South African Journal of International Affairs, 24:2, 115-135, https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2017.1343681

Masters, L. & Hierro, L. 2016. Reviewing a Decade of the EU-South Africa Strategic Partnership. Internet: https://southafrica.fes.de/fileadmin/user_upload/documents/Event_EU-SA_Report_final.pdf. Access: 14 May 2023.

Masters, L. 2014a. The EU and South Africa; Towards a New Partnership for Development. In C. Castillejo (Ed.), New Donors, New Partners? EU Strategic Partnerships and Development (pp. 53–62). Brussels: European Strategic Partnerships Observatory.

Masters, L. 2014b. The EU and South Africa: Towards a New Partnership for Development. Policy Brief 11. Brussels: European Strategic Partnership Observatory (ESPO).

Mathekga, R. 2022. South Africa confronts cascading fallout of Russia’s war. Geopolitical Intelligence Services. Internet: https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/africa-neutrality-russia/. Access: 7 May 2023.

Matibe, P. 2023. US Republican lawmakers launch bill denouncing South Africa’s naval exercises with China and Russia. Defence Web. Internet: https://www.defenceweb.co.za/featured/us-republican-lawmakers-launch-bill-denouncing-south-africas-naval-exercises-with-china-and-russia/. Access: 14 May 2023.Mzekandaba, S. SA’s ICT sector grows despite economic slowdown. IT Web Ltd.

Mthembu, P. 2017. Situating the European Union within South Africa’s foreign policy calculus, South African Journal of International Affairs, 24:2, 249-260, https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2017.1341332

Soko, M. & Qobo, M.2017.Economic, trade and development relations between South Africa and the European Union: The end of a strategic partnership? A South African perspective, South African Journal of International Affairs, https://doi.org/10.1080/10220461.2017.1338162

Mohammed, H. 2023. Why South Africa continues to be neutral in Ukraine-Russia War. Aljazeera News. Internet: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/1/24/why-is-south-africa-neutral-in-ukraine-russia-war. Access: 46 May 2023.News24. 2018. SA’s cancellation of bilateral investment treaties – strategic or hostile? Internet: https://www.news24.com/fin24/sas-cancellation-of-bilateral-investment-treaties-strategic-or-hostile-20180928-3. Access: 14 May 2023.

News24. 2023. Bitter battle: Ramaphosa slams ‘unfair’ EU citrus trade rule. Internet: https://www.news24.com/fin24/economy/bitter-battle-ramaphosa-slams-unfair-eu-citrus-trade-rule-20230425. Access: 15 May 2023.

Parliamentary Monitoring Group (PMGa). 2022. Report on South Africa’s Trade Portfolio. Internet: https://pmg.org.za/committee-meeting/36168/. Access: 14 May 2023.

Parliamentary Monitoring Group (PMGb). 2022. Minister of International Relations and Cooperation Budget Speech, responses by DA, ACDP, IFP, EFF. Internet: https://pmg.org.za/briefing/34897/. Access: 14 May 2023.

Ramaphosa, C. 2023. President Cyril Ramaphosa: South Africa’s Foreign Policy and upcoming BRICS Summit. Internet: https://www.gov.za/speeches/president-cyril-ramaphosa-south-africa%E2%80%99s-foreign-policy-and-upcoming-brics-summit-20-aug-20. Access: 22 August 2023.

Reuters. 2023. South African farmers want WTO dispute declared over EU citrus rules. Internet: https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/safrican-farmers-want-wto-dispute-declared-over-eu-citrus-rules-2023-08-04/. Access: 7 August 2023.

SADC-EU EPA Outreach South Africa. n.d. ANNUAL DIGEST 2021 SA-EU trade under the SADC-EU EPA1 An update on trade-related matters between South Africa and the European Union. Internet: https://sadc-epa-outreach.com/images/files/EPA_Annual_Digest__2021_Final.pdf. Access: 22 August 2023.

Smith, E. 2023. Russia, South Africa and a ‘redesigned global order’: The Kremlin’s hearts and minds machine is steaming ahead. Internet: https://www.cnbc.com/2023/01/26/russia-south-africa-and-a-redesigned-global-order.html. Access: 7 May 2023.

South African Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO). 2022. South Africa has maintained a consistent position on the Israel-Palestine question. Internet: https://www.dirco.gov.za/blog/2022/01/27/south-africa-has-maintained-a-consistent-position-on-the-israel-palestine-question/. Access: 4 May 2023.

South African Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO). 2011. White Paper on South Africa’s Foreign Policy.

South African Government. 2023. President Cyril Ramaphosa: Oral replies to questions in the National Assembly. Internet: https://www.gov.za/speeches/president-cyril-9-mar-2023-0000. AccessL 15 August 2023.

Teevan, C & Domingo, E. 2022. The Global Gateway and the EU as a digital actor in Africa. ECDPM. https://ecdpm.org/work/global-gateway-and-eu-digital-actor-africa

The Economist. 2023. Why South Africa is drifting into the Sino-Russian orbit. The Economist. Internet: https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2023/02/19/why-south-africa-is-drifting-into-the-sino-russian-orbit?utm_medium=cpc.adword.pd&utm_source=google&ppccampaignID=18151738051&ppcadID=&utm_campaign=a.22brand_pmax&utm_content=conversion.direct-response.anonymous&gclid=Cj0KCQjwi46iBhDyARIsAE3nVrZxORQQz7jACyVVNSy6p3YS-aXUWasV4c5QY7SCeAF1IMtpihSV3gUaArCEEALw_wcB&gclsrc=aw.ds. Access: 6 May 2023.

The South African Government. 2018. President Cyril Ramaphosa: South Africa-European Union media briefing. Internet: https://www.gov.za/speeches/cyril-ramaphosa-south-africa-european-union-media-briefing-15-nov-2018-0000. Access: 22 August 2023.

Tralac. 2022. Southern African Development Community-European Union Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA): Booklet. Internet: https://www.tralac.org/publications/article/15686-southern-african-development-community-european-union-economic-partnership-agreement-epa-booklet.html. Access: 14 May 2023.

VOA. 2023. German, French Ministers Call for African Permanent Seats on UNSC. Internet: https://www.voanews.com/a/german-french-minsters-call-for-african-permanent-seats-on-unsc-/6917232.html. Access: 27 May 2023.

[1] The Lisbon Treaty signifies the most recent stage in the progressive evolution of the EU from a relative self-contained entity to one that aspires to assume a prominent role on the world stage. It signifies a notable transition in the EU’s focus , shifting from prioritizing peace, well-being, and prosperity to a heightened emphasis on addressing global concerns.