- Ankara is pursuing a radical revision of the regional status quo by projecting power in neighboring regions with increasing aggression and disregard for international legality.

- Turkey moved from a security-based to a power-based foreign policy and took advantage of the power vacuum in Eastern Mediterranean to make a bid for regional hegemony by resorting to the use of hard power.

- The Turkish army developed autonomous expeditionary capabilities, bolstered by a strengthened national defense industry. The lessons learned in Syria clearly informed the series of Turkish foreign policy moves that followed.

- A revisionist Turkey involved itself in all regional theaters of conflict, fomenting instability in the region while also reaping strategic and economic benefits.

- These interventions shaped Turkish-Russian competitive cooperation and strategic realignment. Since 2016 the relationship has evolved into something almost symbiotic, with the two countries coordinating their presence on multiple fronts.

- The two countries are drawn to one another by their shared authoritarian models of governance and similar strategic cultures and operational codes:

- Both countries are revisionist, aggressive and assertive on their peripheries.

- Both countries claim to be surrounded, which serves as a pretext for their unilateral actions.

- Both countries have militarized their foreign policy by conducting hybrid warfare, using surrogate forces and coercing countries that resist.

- Ankara has developed a web of interdependence with Moscow, primarily because it wants to gain strategic autonomy from the West, but their interdependence is asymmetrical in Russia’s favor.

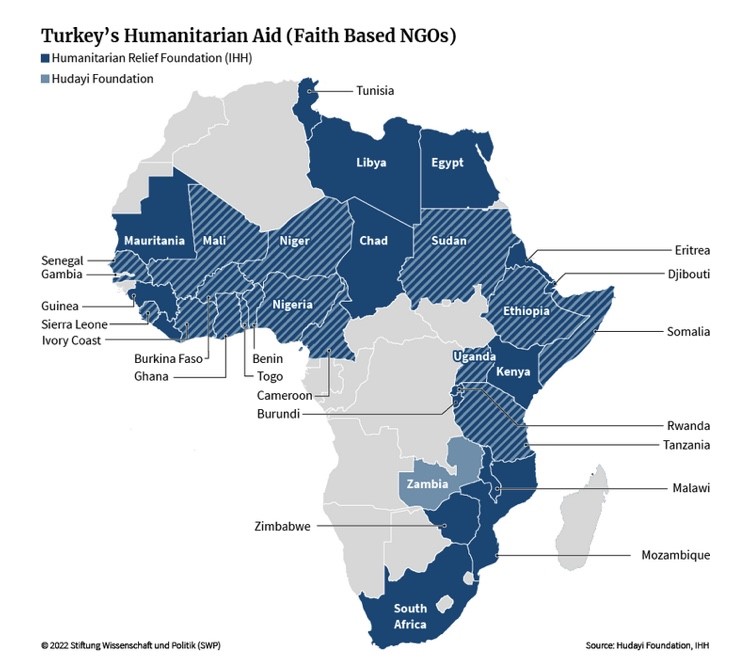

- Ankara’s Africa pivot in search of markets, resources and diplomatic influence is indicative of its wider trans-regional aspirations. This political, economic, military and cultural foray is well rooted in Turkey’s self-perception as “emancipatory actor” with a trans-regional role.

- The postcolonial discourse of the Turkish President has served both domestic revisionist policies and his diplomatic approach to Muslim countries in the African continent.

- Turkey has capitalized on its religious ties with the Muslim world extensively. Sunni Islam has become a decisive force multiplier and essential soft power tool in Ankara’s foreign policy. In Muslim-majority countries, Turkish religious institutions educate imams and restore or open new mosques, as well as training the next generation of Africa’s elites.

- To further deepen its economic ties with Africa, Turkey has prioritized weapons sales and military training. Drone exports have also proven an extremely useful foreign policy instrument.

- “Blue Homeland’s” scope is continental, even global. Implicit to the concept is the need for Turkey to dominate the Mediterranean in order to reclaim the mercantile and maritime power once held by the Ottomans. It is through this doctrine that Ankara seeks to dominate the Eastern Mediterranean, the mandatory point of passage for trade routes linking Europe to the Indian Ocean and, by extension, the markets of Southeast Asia. By controlling the sea routes from the Black Sea and the Suez Canal to the Central Mediterranean, Turkey would control the major eastern transit routes to Europe and become the undisputable trans-regional power.

- To give a legal veneer to the “Blue Homeland” doctrine, Turkey signed an illegitimate agreement with Libya’s GNA in November 2019 to establish a common maritime border. Employing this agreement in the framework of this doctrine, Turkey projects power not only in the Aegean Sea or the Eastern Mediterranean, but also across the Central Mediterranean.

- Understanding the “Blue Homeland” as the heart of Turkey’s quest for strategic autonomy explains why Ankara remains an intransigently belligerent actor in the Eastern Mediterranean.

- Turkey’s political and security elites reached the conclusion that major ideological battles would no longer stoke competition between ideologically different blocks, rendering international relations essentially transactional.

- Ankara has increasingly taken advantage of NATO to settle scores or mend fences as best suits, with little regard for repercussions or the wider interests of the alliance.

- Turkey’s asymmetrical interdependence with Russia makes it prohibitive for Ankara to align with other NATO member states and cut economic ties with Moscow, even if she wanted to.

- NATO is supposed to be “a unique community of values committed to the principles of individual liberty, democracy, human rights and the rule of law”– and Turkey fails on all accounts. In an organization of 30 member states, each of whom possesses a veto, adherence to common values and principles is an absolute necessity if the Alliance is to function properly.

- Turkey envisages itself as a pivotal power – an indispensable partner with whom Washington, Moscow, or even Beijing can achieve effective agreements in the region. Turkey wants to increase its relative power vis-à-vis the “West” in order to bargain with it on an equal footing, without cutting ties in any decisive way.

Read here in pdf the Policy paper by Alexandros Diakopoulos, Vice Admiral (Retd); Former National Security Advisor; Emeritus Commandant of the National Defense College; Senior Policy Advisor, ELIAMEP and Nikos Stournaras, Research Assistant, ELIAMEP.

The Unique Challenges of the Eastern Mediterranean

Crucial petroleum and gas exports from the Gulf states to European markets form a large part of this cargo, as every year around 70% of Europe’s energy demands are met by fuel transported through the Mediterranean.

At the crossroads of three continents, the Eastern Mediterranean is a uniquely diverse, strategic and consequently contested area. It makes up a large part of the MENA region, encompassing nine littoral states and two critical maritime choke points: the Dardanelles and the Suez Canal. Its Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs) remain crucial for trade and energy shipments globally, with estimates suggesting that trade flows within the Mediterranean account for as much as 25% of all international seaborne trade[1]. As the Eastern Mediterranean provides the shortest maritime route between Asian and European markets, it is estimated that almost 12% of global trade and over 1 trillion USD worth of goods pass through the Suez Canal annually. Crucial petroleum and gas exports from the Gulf states to European markets form a large part of this cargo, as every year around 70% of Europe’s energy demands are met by fuel transported through the Mediterranean[2]. These characteristics have rendered the Eastern Mediterranean a crucial geostrategic pivot, control over which comes with far-ranging implications.

Adding to the region’s importance as a transit hub, past decades have also revealed that the Eastern Mediterranean has significant energy deposits.

Adding to the region’s importance as a transit hub, past decades have also revealed that the Eastern Mediterranean has significant energy deposits. A 2010 United States Geological Survey study estimated that the Levant and Nile Delta basins could hold a mean of 122 and 223 trillion cubic feet of recoverable gas respectively – more than enough to turn the region into an energy hot spot. However, multidimensional problems make exploitation of these reserves difficult. Many have been discovered in deep waters and are expensive to extract, with local infrastructure and market deficits compounding the technical challenges. The complex geopolitical realities of the region also threaten the exploitation of these reserves, which is a challenge organizations such as the East Med Gas Forum seek to mitigate[3].

Washington’s pivot to Asia and relative decline in interest in the MENA region has also created a power vacuum, spawning new rivalries among regional and international actors.

This juncture of different political cultures, paired with a tense strategic environment characterized by intrastate and interstate fault lines, generates chronic instability. Washington’s pivot to Asia and relative decline in interest in the MENA region has also created a power vacuum, spawning new rivalries among regional and international actors[4]. By extension, relations between the Middle East and international powers have become multi-polar in nature. In this context, major powers are actively competing for influence in the region, with Russia’s role in regional security – as well as China’s in the regional economy[5] – increasing, along with the role regional powers now play in shaping Eastern Mediterranean affairs[6].

From Security to Power: Turkish Involvement in Crises across the Region

A revisionist Turkey involved itself in every regional theater of conflict, fomenting instability in the region while also reaping strategic and economic benefits.

With the “Arab Spring” tilting regional balances, the Eastern Mediterranean once again became a contested space. In Ankara, this was evidently perceived as a unique chance to make a bid for regional hegemony by resorting to the use of hard power. Chronic instability further promoted military power as an essential component of foreign policy, given the structural impacts of the power vacuums created[7]. The retreat of US strategic attention from the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East – going back to the “Asia pivot” under the Obama administration – was viewed by Turkey’s President Erdoğan as an opportunity to fill the power vacuum[8]. Indeed, a revisionist Turkey involved itself in every regional theater of conflict, fomenting instability in the region while also reaping strategic and economic benefits. To quote a former Turkish diplomat: “Turkish policy will respond accordingly” to Washington’s “rudderless or absentee policy in the Middle East” and the EU’s incapacity to engage “effectively with developments beyond its borders[9].”

The Turkish army employed a mix of traditional approaches, counterterrorism tactics and advanced military technology, including the deployment of the Bayraktar TB2 drone, which drastically changed the situation on the ground.

The Turkish army developed autonomous expeditionary capabilities, bolstered by a strengthened national defense industry. Ankara intervened in northern Syria first, with unparalleled ambition. It employed a mix of traditional approaches, counterterrorism tactics and advanced military technology, including the deployment of the Bayraktar TB2 drone, which drastically changed the situation on the ground.

Technological innovations, such as the large-scale production and development of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), not only helped Turkey achieve its strategic goals; it also enabled Ankara’s involvement in the first place. Turkey was an early adopter of drones, but when Israeli drone exports stopped after a falling out between the two states in 2010, and the U.S. refused to approve Predator drone exports to Turkey, the operational demands of Ankara’s counterinsurgency against the PKK made autonomous drone development capabilities necessary. Consequently, new Turkish firms were awarded contracts to design drones in the mid-2000s[10].

These involvements strengthened Turkish resolve to conduct a more aggressive, unilateralist foreign policy aimed at achieving “strategic autonomy”.

The Bayraktar TB2 UCAV, first deployed in 2016, has since become a favorite in counterinsurgency operations within Turkey, as well as in northern Iraq and Syria. The drone received further acclaim during the Turkish intervention in Libya and the second Nagorno-Karabakh war, where it managed to combine combat effectiveness with low human and operational costs, introducing a paradigm shift in the modern conception of air power[11]. These involvements strengthened Turkish resolve to conduct a more aggressive, unilateralist foreign policy[12] aimed at achieving “strategic autonomy”. As of January 2022, Turkey’s security forces have a total of 140 Bayraktar drones in service, complemented by 28 ANKA S and three recent Akinci models[13].

Turkey’s military interventions have resulted in increasingly tense relations with the West, a strategic realignment with Russia, and new leverage over the EU regarding the control of refugee flows.

The lessons learned in Syria clearly informed the series of Turkish foreign policy moves that followed. Through such interventions, Ankara could project power and secure a front seat at the negotiating table: Turkey, along with Russia and Iran, created the Astana mechanism for Syria[14], and Turkey has also been an indispensable party at the Berlin conferences on Libya[15]. Overall, Turkey’s military interventions have resulted in increasingly tense relations with the West, a strategic realignment with Russia, and new leverage over the EU regarding the control of refugee flows[16]. Of all these developments, Turkey’s strategic realignment with Russia is potentially the most consequential.

Fig.1: Mapping the full scale of Turkish involvement across the Eastern Mediterranean and neighboring regions[17]

“Competitive cooperation” with Moscow and Turkey’s Global Aspirations

The relationship between Russia and Turkey is one of the most important bilateral relationships in Eurasia today. Although they are considered to be historical enemies, their relationship has grown far more complex. […] Even if they often appear to be on opposing sides, their coordination is remarkably reminiscent of a classical ballet pas de deux.

The relationship between Russia and Turkey is one of the most important bilateral relationships in Eurasia today. Although they are considered to be historical enemies, their relationship has grown far more complex. During the Cold War, although on opposing sides, Turkey received more Soviet aid than any other country outside the Warsaw Pact[18]. However, since 2016, the relationship has evolved into something almost symbiotic, with the two countries coordinating their presence on multiple fronts. The two countries have established a “strategic understanding”, which has been aptly characterized as “conflictual camaraderie.”[19] Even if they often appear to be on opposing sides, their coordination is remarkably reminiscent of a classical ballet pas de deux.[20]

In those regions where their ambitions collide, Ankara and Moscow have increasingly pursued a condominium approach aimed at minimizing the influence of Western states and institutions.

Both countries have exploited the geopolitical vacuum on their periphery to increase their influence and establish a presence in the Greater Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa. In those regions where their ambitions collide, Ankara and Moscow have increasingly pursued a condominium approach aimed at minimizing the influence of Western states and institutions[21]. By backing opposing sides in proxy conflicts, then working together to negotiate their resolution, Moscow and Ankara have both gained influence at the expense of Western actors[22]. The two countries are drawn to one another by their shared authoritarian models of governance and similar strategic cultures and operational codes[23]. They also share a political culture which clearly prioritizes national security and sovereignty over liberal values[24]. In the same vein, both countries are negatively predisposed toward a liberal international order governed by the rule of law, because it would constrict them[25]. Erdoğan’s multipolar worldview mirrors Putin’s, with both deviating from the mindset of Western liberal elites[26]. Consequently, the Turkish and Russian leaders speak regularly and have broadened their cooperation on a number of fronts[27].

A recent poll indicates that 54% of Russians and a staggering 82% of Turks believe their country doesn’t have the status it deserves in comparison with other countries in the world.

Historically, both countries have been plagued by post-imperial status crises and a subsequent yearning for international grandeur[28]. This is evident even at the level of popular sentiment: a recent poll indicates that 54% of Russians and a staggering 82% of Turks believe their country doesn’t have the status it deserves in comparison with other countries in the world[29]. Four out of five Turks support Ankara being more active on the world stage, with 56% believing that the Turkish army should play a role in this effort[30]. Ankara and Moscow both display “status anxiety” in the current world order, with their actions being driven by the belief that there is a link between great power status and dominance of geopolitical spaces[31]. As a result, Russian foreign policy pursues a special role for Moscow in the territories of the former Russian Empire and USSR (the “near abroad”), while Turkey perceives its long and unique history with former Ottoman territories as giving it carte blanche to interfere, influence and ultimately exert control over these regions in its own way[32].

The footprints of this Russo-Turkish “competitive cooperation” are all over the region. Turkey has helped Moscow accomplish its strategic objectives in the Levant and the Eastern Mediterranean[33]. By obtaining the withdrawal of U.S. forces from north-eastern Syria, Turkey facilitated a takeover of their bases by Russia, at a time when Russia also established a permanent air base at Khmeimim, near Lattakia.

By deploying forces and assets in support of Libya’s Government of National Accord, Turkey prompted a Russian military build-up in the center and east of the country[34]. The presence of one country’s surrogate forces “legitimized” the presence of the other’s, perpetuating the presence of foreign militants in the country and keeping Libya unstable. In Nagorno-Karabakh, Russia and Turkey brushed the OSCE Minsk Group aside, minimizing all Western influence. In Mali, the political and religious inroads made by Turkey, combined with the deployment of the Russian Wagner Group, are contributing to the sidelining of the French and EU presence[35].

Their multiple political, security and economic ties make the two countries interdependent, but their interdependence is asymmetrical in Russia’s favor.

Their multiple political, security and economic ties make the two countries interdependent, but their interdependence is asymmetrical in Russia’s favor. By maintaining a close but asymmetrical relationship with Turkey, Russia has managed to drive a wedge between it and its key Western partners, including the United States and NATO[36]. Indeed, encouraging Turkey’s regional ambitions in ways that complicate its relationship with Western allies has long been an important component of Russian policy. The Russian S400 missile systems now deployed in Turkey are one such example: from a strategic perspective, Ankara’s procurement of Russian missile systems gave Moscow a considerable advantage on its southern flank, but also contributed to Turkey’s expulsion from the F-35 program[37]. Russian support for Turkey’s efforts to consolidate control over East-West energy transit by becoming an energy hub is another example. Russia’s pursuit of bilateral energy deals with Turkey – notably the Blue Stream and TurkStream pipelines, along with the USD 20 billion Akkuyu Nuclear Power Plant project – has bolstered Turkey’s leverage with the EU, but also left it dependent on Russian gas, nuclear fuel, and technical expertise[38]. The Akkuyu NPP will reinforce Turkey’s dependence on Russia for the next six decades[39], a dependence that is already deep, with Turkey also importing 70% of its wheat supplies from Russia[40] and relying on the country for almost a fifth of its total tourist arrivals[41]. Thus, while both sides have invested in the military, economic and strategic aspects of their multifaceted relationship, it is clear that Russia maintains the upper hand.

Aside from their deepening interdependence, there are wider similarities between Russian and Turkish mentalities. […] Both countries have also militarized their foreign policy by conducting hybrid warfare, using surrogate forces and coercing countries that resist.

Aside from their deepening interdependence, there are wider similarities between Russian and Turkish mentalities. Both countries are revisionist, aggressive and assertive on their peripheries, while domestic authoritarianism feeds into their aggressive diplomacy. Moreover, as respect for the rule of law declines both within and beyond their borders, they are increasingly two sides of the same coin: their leaders face no institutional obstacles, having done away with any semblance of the rule of law, while their citizens have filed more complaints with the European Court of Human Rights than the citizens of any other nation[42]. Both countries suppress media freedom[43], prosecute and detain human rights activists[44], and disregard European Court of Human Rights verdicts in defiance of Council of Europe decisions. Notable examples include the incarceration of the well-known human rights activist and philanthropist Osman Kavala, and the detention of Selahattin Demirtaş and eight other democratically-elected Peoples’ Democratic Party members in Turkey[45], and the jailing of Alexei Navalny in Russia[46].

Both countries have also militarized their foreign policy by conducting hybrid warfare, using surrogate forces and coercing countries that resist. The November 2021 migrant crisis on the EU-Belarus border, which was sponsored and facilitated by Moscow[47], echoed lessons from the February-March 2020 migrant crisis on the Greece-Turkey land border in Thrace, which was staged by Ankara[48]. Like Russia, Turkey will implement military interventions and occupy neighboring territory when necessary. Moscow has occupied Crimea and large parts of eastern and southern Ukraine and effectively controls Transnistria, Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Ankara effectively controls northern Cyprus, directly governs large parts of northern Syria, and has a dominant military presence in both northern Iraq and western Libya.

The symmetry in their security narrative is astounding: both countries claim to be surrounded, which serves as a pretext for their unilateral actions.

The symmetry in their security narrative is astounding: both countries claim to be surrounded, which serves as a pretext for their unilateral actions. While Russia claims to fear encirclement by NATO, Ankara also denounces various regional cooperation initiatives such as the East Med Gas Forum[49], the “Philia Forum,” and 3+1 initiatives as elements of a plan to exclude and encircle Turkey. Russia is demanding the withdrawal of NATO forces from its former Soviet sphere of influence, while Turkey is demanding the demilitarization of Greek islands. Russia threatens (and ultimately wages) war on countries which court NATO partnerships, while Turkey threatens war if Greece expands its territorial waters to 12 nautical miles. Russia’s rationale for invading and occupying Crimea is identical to Turkey’s rationale for invading and occupying the northern part of Cyprus: the “protection” of ethnic minorities severed from the motherland after their empires fell. In conclusion, there is a striking similarity between Russia’s rhetoric and aggressiveness toward Ukraine and Turkey’s moves against Greece and Cyprus, which extends from their military aspects to the frequent references back to imperial history.

Ankara has developed a complicated web of interdependence with Moscow, primarily because it wants to gain strategic autonomy from the West[50], but it has come at a price: namely, the asymmetrical nature of this interdependence. Nevertheless Turkey seems to accept this asymmetry as a necessary evil as she pursues autonomy from the West with a view to becoming a trans-regional power.

Turkey’s Anti-Colonial Pivot to Africa

Ankara’s Africa pivot in search of markets, resources and diplomatic influence is indicative of its longstanding trans-regional aspirations.

Turkey’s growing foreign policy ambitions are not limited to its immediate neighborhood. Ankara’s Africa pivot in search of markets, resources and diplomatic influence is indicative of its longstanding trans-regional aspirations.

From 2009 to 2021, the number of Turkish embassies in Africa rose from 12 to 43. Trade with the continent has expanded greatly, to USD 29 billion last year, of which USD 11 billion was with sub-Saharan Africa – an almost eight-fold increase since 2003. According to Turkish officials, Ankara has invested some USD 78 billion in African construction projects, including airports, stadiums and mosques. In the field of transport, Turkish Airlines has expanded from flying to just four African cities in 2004 to more than 40 today[51].

This unparalleled economic, political, military and cultural foray is rooted in Turkey’s self-perception as an “emancipatory actor” with a trans-regional role. Formulated under Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu (2009-2014), the “strategic depth” doctrine suggests that – due to its location at the crossroads between Asia, Africa and Europe – Turkey has the unique advantage of being able to make openings in every direction. In this context, Davutoğlu made the case for an extroverted and proactive approach to regional involvement, especially in the Muslim world, and the approach has outlived his tenure at the Foreign Ministry[52].

Turkey has capitalized on its religious ties with the Muslim world extensively.

In the spirit of this doctrine, Turkey has capitalized on its religious ties with the Muslim world extensively. Especially after Erdoğan’s break with the Gülen Movement in 2016 and subsequent alliance with nationalist and Eurasianist elements, Sunni Islam has become a decisive force multiplier and essential soft power tool in Ankara’s foreign policy. Despite being a constitutionally secular state, Turkey’s Directorate of Religious Affairs (Diyanet) has a budget larger than most of the country’s universities; the Turkish Statistics Institute (TUIK) estimates it at over USD 1.87 billion[53]. This large investment is commensurate with Ankara’s religious overtures worldwide. The AKP government has spent almost half a billion dollars building over 100 mosques abroad, with the Diyanet overseeing more than 2,000 mosques outside Turkey[54]. Diyanet representatives operate across the Balkans, North Africa and Central Asia, as well as in Western European countries with large populations of Turkish migrants.

Through this ideological instrumentalization of Islam, Turkey seeks to position itself as a third power in the global struggle to win hearts and minds in the Islamic world.

President Erdoğan has presented himself as a leader of the global Umma, a move that pairs well with his callbacks to the Ottoman past in the Balkans, the Middle East, and at home. The Turkish President displays a midset emphasizing the purported religious, cultural and ethical superiority of Islam over the West, with Erdoğan’s propagandists painting the West in adversarial terms, employing a distinctly anti-Semitic rhetoric[55]. Through this ideological instrumentalization of Islam, Turkey seeks to position itself as a third power in the global struggle to win hearts and minds in the Islamic world. By merging Turkey’s Islamic heritage with a militant anti-colonial political discourse, Erdoğan seeks to challenge both Iran’s efforts to export its revolution and Saudi attempts to monopolize religious influence over the world’s Muslims[56]. Nowhere is this more evident than in Turkey’s fervent espousal of the “Arab Spring” in North Africa and the Middle East[57].

Turkey has focused specifically on the Sahel and the Horn of Africa, emphasizing the shared religious ties which are its key differentiator from France and other Western powers.

Across the continent, Ankara continues to champion anti-colonial and anti-Western sentiments, gaining significant sway through soft power methods which range from humanitarian aid to providing scholarships and language lessons[58]. Its policy has hinged upon challenging the primacy of European states and intervening in their sphere of influence, primarily with the economic and diplomatic support of local pro-Ankara elements[59]. In Muslim-majority countries, Turkish religious institutions educate imams and restore or open new mosques, as well as training the next generation of Africa’s elites; the state-controlled Maarif Foundation now operates 175 schools in 25 countries, educating almost 18,000 students. Turkey has focused specifically on the Sahel and the Horn of Africa, emphasizing the shared religious ties which are its key differentiator from France and other Western powers. The prime target of Turkey’s anti-colonial discourse is France, as revealed by Turkish efforts to curb French influence in the Sahel and West/North Africa. Ankara has taken advantage of France’s colonial history to portray itself as an “anti-colonial” alternative, promoting the image of an equal partner formulating “win-win” agreements[60].

Fig. 2: Visualizing Turkey’s Activism in Africa (Πηγή: https://www.cats-network.eu/topics/visualizing-turkeys-activism-in-africa)

Accustomed to stirring up anti-Western patriotic sentiment at home, Erdoğan uses the same rhetoric to present himself as an emancipator who represents the developing world and Muslims across the globe.

The Turkish President’s postcolonial discourse has served both his domestic revisionist policies and his diplomatic approach to Muslim countries in the African continent. President Erdoğan has employed it both to justify Turkey’s democratic backsliding and to deflect Western criticism of Turkish foreign policy. His use of Islamic and Ottoman-inspired symbolism has allowed him to solidify domestic support and portray the West as a rival[61]. At a meeting with African students, President Erdoğan stated: “They come from European countries and take away all your natural resources like gold and precious stones; they take them back to their country and leave nothing for you[62].” On a trip to Zambia, the Turkish President stressed that Turkey is “not going to Africa to take their gold and natural resources, as Westerners have done in the past[63].” On another occasion, on September 1st 2020, he declared: “The era of those who for centuries have left no region unexploited from Africa to South America, no community unmassacred and no human being unoppressed, is coming to an end.” Accustomed to stirring up anti-Western patriotic sentiment at home, Erdoğan uses the same rhetoric to present himself as an emancipator who represents the developing world and Muslims across the globe[64].

In contrast to these frequent rants against the West, Ankara has offered at best tepid criticism of China’s systematic oppression of the Uighurs[65] (a population that is both Turkic and Muslim[66]). This selectivity in who gets criticized when is indicative of the way with which Ankara instrumentalizes religion as a tool against the West.

To further deepen its economic ties with Africa, Turkey has prioritized weapons sales and military training.

To further deepen its economic ties with Africa, Turkey has prioritized weapons sales and military training. Turkish military bases in Libya and Somalia are complemented by military cooperation agreements with with 28 African countries, most recently Nigeria, Senegal, Niger, Chad and Togo. Moreover with 18 out of those 28 countries, Turkey has signed Defense Industrial Cooperation Agreements as well. This strengthening of military ties is further highlighted by the increasing proportion of African ambassadors to Turkey who are generals (active or retired)[67].

Purchasing the drone ties countries to the supplier, making new operators dependent on Turkey for training, spare parts and regular upgrades.

Drone exports have also proven an extremely useful foreign policy instrument. The Bayraktar TB-2 has spearheaded Turkish defense exports, which rose from $248 million in 2002 to $3 billion in 2019[68]. In 2021, Turkey’s arms sales in sub-Saharan Africa surged seven-fold to $328m. In the first two months of 2022, they approached $140m. Morocco, Tunisia, Niger and Ethiopia have acquired TB2 UAVs, while many other countries, including Angola, Nigeria and Rwanda, are thinking of buying them[69]. Purchasing the drone ties countries to the supplier, making new operators dependent on Turkey for training, spare parts and regular upgrades. Leveraging this dependence has given Ankara access to Nigerian minerals and LNG, while Ethiopia was coerced into shutting down Gülenist schools in exchange for drones[70].

Unlike the US, which stops weapons sales to African countries which use them to commit war crimes, Turkey seems unconcerned about how its weaponry is used. The TB-2s that turned the tide in Ethiopia’s civil war have reportedly killed dozens of civilians. Turkey’s silence on the issue has rendered it one of Ethiopia’s most trusted allies. Somalia’s former president, Mohamed Abdullahi Mohamed, used Turkish-trained soldiers to contain his rivals. For Turkey, non-interference is a crucial selling point[71].

This combination of inflammatory anti-Western rhetoric, increasing arms sales, and Western withdrawal has the capacity to exacerbate regional fault lines with long-term implications for other theaters, including the war on terror.

This militarist expansion and proliferation of arms, combined with the inflow of mercenaries from Libya, has the potential to further destabilize African regions that are key to European interests, especially in the light of the anti-Western and anti-colonial discourse promulgated by Ankara and coupled with its track record of using jihadi movements for its own purposes (e.g. Hayat Tahrir al-Sham in Syria)[72]. This combination of inflammatory anti-Western rhetoric, increasing arms sales, and Western withdrawal has the capacity to exacerbate regional fault lines with long-term implications for other theaters, including the war on terror. However, Turkey’s long-term success in this transregional strategy ultimately hinges on control of the region which bridges all its different theaters of activity: the Eastern Mediterranean.

The “Blue Homeland” Doctrine as the Centerpiece of Turkish Grand Strategy

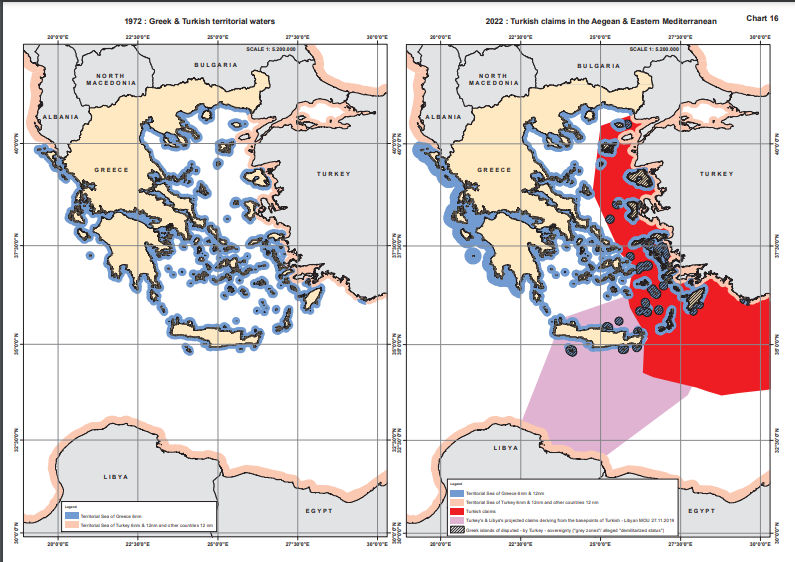

During a visit to Istanbul’s National Defense University in 2019, Erdoğan posed in front of a map of Turkey entitled “Mavi Vatan,” or “Blue Homeland”. It depicted Turkey’s maritime borders as encompassing the islands of the Eastern Aegean, demarcating a 462,000 square kilometer area around Asia Minor[73] – Ankara’s maximalist claims that encroach upon the sovereign rights of Greece and Cyprus.

The “Blue Homeland” concept is popular with diverse ideological movements, eliciting supporters across the political spectrum – both President Erdoğan’s AKP party and the Kemalist opposition (CHP) fervently support it.

The “Blue Homeland” doctrine is the brainchild of two radical admirals: the Eurasianist Cem Gürdeniz, who conceived it, and Cihat Yaycı, who helped promote it. The “Blue Homeland” concept is popular with diverse ideological movements, eliciting supporters across the political spectrum – both President Erdoğan’s AKP party and the Kemalist opposition (CHP) fervently support it. That said, “Mavi Vatan” seems to resonate the most with the ultranationalists, which is to say the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) and the small but influential Eurasianist movement[74].

The ultranationalists and Eurasianists are bound together by a shared disdain for the United States and what they often term the “Atlantic framework”.

As the Turkish government uses Eurasianism to curtail pluralism and promote ultranationalism at home (notably after 2016), Eurasianist ideologues are increasingly gaining greater sway over foreign policy, despite internal factionalism and a small political base. Although less elaborate than its Russian counterpart, Turkish Eurasianism has evolved to produce significant policy proposals for Turkey’s nationalist, militarist and revisionist diplomatic agenda, solidifying the perception among Turkey’s intelligentsia that a post-Western world is in the offing[75]. Although they are focused on different geopolitical areas, “Mavi Vatan” and Eurasianism complement each other, cultivating a common sense of distrust of Western powers and advocating the need for alternative partnerships[76]. In addition, the ultranationalists and Eurasianists are bound together by a shared disdain for the United States and what they often term the “Atlantic framework”[77].

Implicit to the concept is the need for Turkey to dominate the Mediterranean in order to reclaim the mercantile and maritime power once held by the Ottomans.

Although initially seen by external observers as Turkey laying claim to energy reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean, the scope of the “Blue Homeland” doctrine is actually continental, even global[78]. It is underpinned in the historical thesis that the Ottoman Empire collapsed as a result of losing its naval power, and extrapolates that for Turkey to regain its rightful place, it needs to acquire the capabilities of a blue-water navy[79]. Exploiting natural resources is only part of the project, whose ultimate goal is control over Eastern transit routes to Europe[80]. Implicit to the concept is the need for Turkey to dominate the Mediterranean in order to reclaim the mercantile and maritime power once held by the Ottomans[81].

This militarization is evident in the diplomatic categorization of littoral states into three groups: allies, structural adversaries and occasional adversaries.

In this context, the “Blue Homeland” strategic vision hinges on an inherently militarist logic, necessitating the use of force. This militarization is evident in the diplomatic categorization of littoral states into three groups: allies, structural adversaries and occasional adversaries[82]. Greece and the Republic of Cyprus are labeled structural adversaries, since the “Blue Homeland” is throttled by their territorial waters and EEZs. To normalize relations, Greece would have to renounce its maritime claims, validating Turkish positions on the status of the Aegean, demilitarize its Eastern Aegean islands, and recognize the Turkish-Libyan maritime border[83]. Should Turkey succeed in this maximalist project, it will be in a position to control the sea routes from the Black Sea and Suez to the Central Mediterranean, fulfilling its ambition of becoming an unsurpassable geostrategic and geo-economic hub connecting Asia, Europe and Africa[84].

Fig. 3: Turkey’s “Blue Homeland[85]”

The phrase “nothing can be done in the Eastern Mediterranean without our consent” is a recurring motto in the statements of Turkish officials.

While former Foreign Minister Davutoğlu saw Anatolia as a node between Europe, Africa and Asia, the Eastern Mediterranean plays a similar role in the “Blue Homeland” doctrine, straddling the Mediterranean basin, the Middle East and the Indo-Pacific space[86]. Notably, in a 2011 speech celebrating the delivery of Turkey’s first native corvette, Erdoğan explicitly stated that Turkey’s “national interests extend from the Suez Canal and the nearby seas to the Indian Ocean[87].” Similarly, the phrase “nothing can be done in the Eastern Mediterranean without our consent” is a recurring motto in the statements of Turkish officials. “In the Eastern Mediterranean, we raised our flag with the Oruc Reis, the Barbaros and the Yavuz, and we showed that nothing can happen in the area that does not involve us,” Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu stated in a foreign policy evaluation meeting for 2020 in Ankara[88]. Similarly, President Erdoğan has repeatedly noted that the only way for the area’s natural gas to be transferred to Europe is through his country: “This business cannot be done without Turkey. It will only happen through Turkey[89].”

Employing this agreement in the framework of the “Blue Homeland” doctrine, Turkey projects power not only in the Aegean Sea or the Eastern Mediterranean, but also across the Central Mediterranean.

To give a legal veneer to this doctrine, Turkey signed an illegitimate agreement with Libya’s GNA in November 2019 which established a common maritime border. In flagrant violation of the Law of the Sea, the deal posits that, regardless of size, islands are not entitled to a continental shelf, meaning that Greek islands east of the 25th meridian are under Turkey’s maritime jurisdiction. According to the EU Commission’s 2021 Turkey report, this agreement “ignored the sovereign rights of Greece in the area concerned, infringed upon the sovereign rights of third states, does not comply with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and cannot produce any legal consequences for third states[90].” Employing this agreement in the framework of the “Blue Homeland” doctrine, Turkey projects power not only in the Aegean Sea or the Eastern Mediterranean, but also across the Central Mediterranean. By strengthening Turkish-Libyan military cooperation and encroaching on Greece’s claimed Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), Turkey has shown that it is not afraid of confrontation with those who would limit its maritime ambitions[91]. At the same time, Turkey’s permanent presence in Libya has also given Ankara unfettered access to the Sahel, another crucial contested region.

This modern “gunboat diplomacy” is proliferating as Ankara asserts control through its power to disrupt, which remains a key element of (implied) ownership.

To pursue its claims, the Turkish navy utilizes area denial tactics to legitimize its control over the “Blue Homeland” area. Ankara has used warships, often while they are participating in the “Mediterranean Shield” mission, to harass scientific research vessels and disrupt their work. This modern “gunboat diplomacy” is proliferating as Ankara asserts control through its power to disrupt, which remains a key element of (implied) ownership[92]. In November 2008, Turkish navy vessels harassed ships contracted by Cyprus to conduct hydrocarbons exploration just to the south of the island. After multiple forays by Turkish research vessels into the Cypriot EEZ, in February 2018 Turkish warships threatened to sink a survey ship within the Cypriot EEZ; contracted by the Italian oil company Eni, the vessel had to make last-minute evasive maneuvers to avoid a collision[93]. In January 2019, escorted by a frigate, the Turkish research ship Barbaros encroached on the Cypriot EEZ once again. A month later, Turkey launched its largest naval exercise to date: over 100 ships took part in the “Blue Homeland” exercise, which spanned the whole of Turkey’s claimed maritime zones from the Black Sea to the Eastern Mediterranean[94]. In 2020, the Turkish survey ships Oruc Reis and Barbaros violated both the Cypriot EEZ and Greece’s claimed EEZ in the Eastern Mediterranean on two occasions, putting the Greek and Turkish navies on high alert after a Turkish frigate collided with a Greek Navy vessel in August[95]. In October 2021, a research vessel under the Maltese flag, the Nautical Geo, was harassed and directly threatened by the Turkish navy while surveying within the Cypriot EEZ[96].

The Courbet incident was only the last in a series of incidents involving the French and Turkish navies in the Eastern Mediterranean.

As part of this campaign, the Turkish navy has no qualms about tempting military escalation to disrupt the current status quo. In June 2020, a Turkish warship’s fire control radars (target illumination) targeted the French frigate Courbet three times off the coast of Libya[97]. The French vessel was part of a NATO mission enforcing the UN arms embargo and was attempting to search a cargo ship operated by a Turkish company. The Courbet incident was only the last in a series of incidents involving the French and Turkish navies in the Eastern Mediterranean: in 2016, a Turkish military vessel fired a distress rocket toward a French warship off Lebanon[98]; in 2018, a second incident took place when a Turkish warship carried out target illumination of a French frigate south of Cyprus[99].

Turkey’s modernization program is supported by its indigenous defense industry and evidently aims to transform the fleet into a fully-fledged blue-water navy, capable of projecting power far from home

It is in this context that the Turkish navy is rapidly expanding and modernizing. Ankara’s Spanish-designed amphibious assault ship TCG Anadolu, which is currently undergoing sea tests, is set to be the first of its kind to host UAVs – a carrier version of the Bayraktar drones[100]. In addition, six new Reis-class submarines (a version of Germany’s Type 214) are set to join the fleet by 2027. Their air-independent propulsion (AIP) grants them weeks of submersion, an ideal condition for East Med flashpoints[101]. Turkey’s modernization program is supported by its indigenous defense industry and evidently aims to transform the fleet into a fully-fledged blue-water navy, capable of projecting power far from home[102].

Moreover, Ankara regularly abuses the ‘NATO’ status of Turkish warships in accordance with its operational needs. In the words of a French Navy Officer: “If a French warship is on a national mission, it will not suddenly declare herself to be a NATO ship in order to justify an action that has nothing to do with NATO or that is directed against another ally. The Turks don’t play fair on that.” Through tactics including the abuse of undersea zone reservations and services like NAVTEX, Turkey implements a status of implied ownership over large sea zones. This de facto area denial and restriction of access increasingly resembles “what China does in the South China Sea,” according to a French general[103].

Turkey’s instrumentalization of its NATO membership at the operational level, through its promotion of operation “Mediterranean Shield”[104] and its abuse of NATO designations, is mirrored by its consistent institutional transactionalism across the alliance’s diverse fora. Ankara’s political priorities often hamper institutional cooperation within the alliance and with NATO partners in Europe and the MENA region.

Turkey in NATO: The odd man out

Turkey’s political and security elites reached the conclusion that major ideological battles would no longer stoke competition between ideologically different blocks, rendering international relations essentially transactional.

As the USSR aggressively expanded its sphere of influence in the aftermath of World War II, Turkey sought security by joining NATO. This choice not only reinforced Ankara’s security vis-à-vis the USSR, it also enabled the modernization of its Armed Forces and significantly increased its geopolitical prestige. At the same time, Turkey became a strategically crucial NATO ally and a major contributor to its missions. For Ankara, membership of NATO was as much a security guarantee as a way of reinforcing its Western identity[105]. After the end of the Cold War, however, Turkey’s security environment changed radically. The diminution of the threat emanating from the erstwhile USSR enabled Ankara to weaken its ties with the West and pursue strategic autonomy. Over the last 20 years – and especially since the failed coup of 2016 – Turkey has drifted away from the West, shedding its Western identity and replacing it with a more nationalist, neo-Ottoman, Islamic posture. Turkey’s political and security elites reached the conclusion that major ideological battles would no longer stoke competition between ideologically different blocks, rendering international relations essentially transactional. Ankara’s transactional mentality reflected its increasingly self-serving and assertive stance within the Alliance. This change in Turkey’s stance was summed up by Daniel Pipes, President of the Middle East Forum, who noted that “Turkey was from 1952 to 2002 a very good ally for NATO, but for the past 20 years, it’s been a very bad one. Not even an ally… it pursues policies that are hostile to NATO, it is aggressive toward NATO members, members like Greece, it engages in the invasion of Syria, it threatens Europe with Syrian migrants. The Turkish government sees Europe as a transactional relationship[106].”

Ankara has increasingly taken advantage of NATO to settle scores or mend fences as best suits, with little regard for repercussions or the wider interests of the alliance.

Ankara has increasingly taken advantage of NATO to settle scores or mend fences as best suits, with little regard for repercussions or the wider interests of the alliance. A notable example is Turkey’s longstanding punitive veto on NATO partnership activities with Egypt in the context of the alliance’s Mediterranean Dialogue, which was only lifted as part of a détente in bilateral relations in 2020[107]. Another instance was Turkey’s consistent veto of a revised defense plan for Poland and the Baltics (known as “Eagle Defender”), which was drafted in the aftermath of Russia’s occupation of Crimea in 2014. Ankara hoped to coerce NATO members into classifying the Kurdish YPG militia as a terrorist organization, but ultimately fell in line in July 2020 after concerted pressure from all NATO members against the backdrop of the Courbet crisis[108]. In March 2017, Turkey blocked NATO cooperation with Austria, a move which stalled the alliance’s partnership activities with 22 countries. The veto was a result of President Erdoğan’s fury at the governments of Germany, Austria and the Netherlands, which had blocked his attempts to campaign among diaspora communities in those nations ahead of a referendum granting the Turkish presidency new powers[109]. Ankara also consistently vetoes EU-NATO partnership activities, pending a resolution of the Cyprus problem deemed acceptable by Ankara[110]. Moreover, Ankara did Russia a favor by diluting NATO’s response to the forced diversion of an EU plane over Belarus in May 2021[111]. In the West, according to Mark Pierini, former EU ambassador and head of delegation to Turkey, this policy is increasingly perceived as à la carte NATO participation hinging on Ankara’s immediate interests[112].

It appears that Turkey does not compartmentalize bilateral political issues and ongoing NATO operational cooperation.

Furthermore, Turkey’s military presence as part of NATO operations in Kosovo and Bosnia was a key element in the economic and cultural headway Ankara has made in the Western Balkans, serving as the basis for more permanent (and exclusively bilateral) forms of defense and security cooperation[113]. It appears that Turkey does not compartmentalize bilateral political issues and ongoing NATO operational cooperation. For example, anecdotal evidence suggests that Turkish officers participating in the NATO-led Stabilization Force (SFOR) – which were supposed to observe strict impartiality between the local communities (Serbs, Croats, Bosniaks) – blatantly favored the Bosniaks[114]. Given the deep relations between Turkey and the Muslim Bosniaks, the operation in Bosnia presents a typical example in which the Turks furthered a nationalist agenda within the framework of a NATO mission and at the expense of its common objectives[115].

As Marshall Billingslea, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute and a former assistant Secretary General of NATO, told Fox News Digital: “It is important to understand that Turkey is playing the same game today that it is always has played in the region with respect to Turkey taking stances that benefits its own interests and run counter to NATO’s […].” [Ankara] is an “independent actor and took stances that had benefits for the Russians,” Billingslea continued, citing Turkey’s closing of access to the Black Sea during the Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008, which prevented U.S. naval vessels from aiding Tbilisi[116].

Turkey’s asymmetrical interdependence with Russia makes it prohibitive for Ankara to align with other NATO member states and cut economic ties with Moscow, even if she wanted to. […] As Finland and Sweden applied for NATO membership as a result of the crisis, Turkey’s objections are delaying (and may derail) the process, providing Russia with diplomatic breathing room.

Ankara’s utilitarian approach toward NATO, both operationally and institutionally, has lately become evident in the precarious balancing act it has performed during the war in Ukraine. Turkey’s asymmetrical interdependence with Russia makes it prohibitive for Ankara to align with other NATO member states and cut economic ties with Moscow, even if she wanted to. Once again, its ambivalent stance has served to water down NATO’s common front, as President Erdoğan prioritized his role as an intermediary in the conflict. Ankara resisted joining the Western sanctions on Russia and has kept its doors open to Russian tourists, hoping to encourage sanctioned Russian oligarchs to stash their wealth in Turkey’s deteriorating economy. High-level Turkish officials have even accused ‘some NATO countries’ of not wanting the war to end, in order to harm Russia.[117] Turkey’s delayed closure of the Straits has little operational effect, as Russia managed to move significant forces into the Black Sea before Turkey invoked the Montreux Convention. Evidently, Turkish airspace was only closed to Russian troop transports when the Turkish army renewed its offensive on Kurdish positions in northern Iraq. Taking advantage of the situation, Ankara is planning to expand operations with another incursion in northern Syria[118]. Lastly, as Finland and Sweden applied for NATO membership as a result of the crisis, Turkey’s objections are delaying (and may derail) the process, providing Russia with diplomatic breathing room. Finalizing NATO’s Nordic expansion would give the West a unique advantage in the Arctic Circle and the Baltic Sea, deterring further aggression at a crucial inflection point – which is why Ankara’s stance is once again the odd man out on the issue.

In light of this history, Turkey’s objections to Swedish and Finnish membership have been met by NATO partners with cynicism.

In all likelihood, the Turkish President is using his leverage at a moment of crisis to extract further concessions from the West[119]. Asli Aydıntaşbaş, senior policy fellow at the European Council on Foreign Relations, highlighted that “It is unlikely that Erdoğan had one specific policy goal in mind, but he will no doubt be expecting to be cajoled, persuaded, and eventually rewarded for his cooperation, as in the past.[120]” After all, it is not the first time that Turkey has blocked an important NATO decision to bargain for privileges: In 2009, Ankara vetoed the appointment of Anders Fogh Rasmussen as NATO secretary-general, only lifting the veto after being promised membership of the European Defense Agency, which increased Ankara’s influence in EU defense affairs[121], while securing the appointment of a Turk as assistant Secretary General[122]. In light of this history, Turkey’s objections to Swedish and Finnish membership have been met by NATO partners with cynicism. Indicatively, Luxembourg’s Foreign Minister Jean Asselborn stated that Erdoğan is merely “pushing up the price” for NATO expansion, alluding to Turkey’s removal from the US-led F-35 program and Ankara’s attempts to extract restitution[123].

Turkey’s aggressively transactional behavior is indicative of deeper and possibly irreversible trends in the Turkish political-security establishment. Burak Bekdil, fellow for the Middle East Forum, noted that “There is also a transactional Erdoğan who is programmed to use the West and its institutions, including NATO, where it’s useful and confronting them when that is useful. Despite the transaction-himself, Erdoğan has been Putin’s man in NATO, too, for ideological reasons as well: His ideological raison d’être is pillared on a rigid anti-West thinking.[124]” In a similar vein, Brig.-Gen. (ret.) Mehmet Yalınalp, who was dismissed from the military following the failed 2016 coup while serving as the head of NATO’s air command strategy in Germany, noted the change of views on NATO: “As the historical purge of thousands of military personnel takes a faster speed, I and my Turkish colleagues observe a considerable rise of ultra-nationalist, anti-Western sentiments within our military and throughout our state departments.” Yalinalp added that new Turkish military personnel in NATO “have a radical mindset, some question the values of NATO and even hate Western organizations, while holding pro-Russia/China/Iran sentiments”[125].

In an organization of 30 member states, each of whom possesses a veto, adherence to common values and principles is an absolute necessity if the Alliance is to function properly.

The transactional mentality with which Ankara has managed the current crisis is indicative of how compromised Turkey is by Russian coercion, but also reveals the extent to which NATO members are willing to accommodate a capricious but indispensable partner[126]. Nevertheless, by constantly accommodating Turkey’s demands, NATO allies have rewarded this transactional behavior and encouraged brinkmanship. This might tempt imitation by other member states who consider this behavior successful, rendering the Alliance completely dysfunctional[127]. NATO is supposed to be “a unique community of values committed to the principles of individual liberty, democracy, human rights and the rule of law”[128] – and Turkey fails on all accounts[129]. These stated principles of the Alliance are not mere grandiloquence; they serve a very practical purpose: in an organization of 30 member states, each of whom possesses a veto, adherence to common values and principles is an absolute necessity if the Alliance is to function properly. The Turkish attitude prompted Joe Lieberman (a former Senator and Vice Presidential candidate) and Mark D. Wallace to write that “NATO’s greatest strategic failure of the past two decades was to play down Putin’s malign intent while underestimating its own members’ capacity for collective resolve. The alliance runs the risk of repeating the same mistake with Erdoğan”[130].

Conclusions

Ankara is pursuing a radical revision of the regional status quo by projecting power in neighboring regions with increasing aggression and disregard for international legality.

Through this paper, we have attempted to demonstrate that Turkey has become a revisionist power with global aspirations and a clear strategy aimed at achieving strategic autonomy. Ankara is pursuing a radical revision of the regional status quo by projecting power in neighboring regions with increasing aggression and disregard for international legality. Turkey’s ambitious strategic posture relies on three pillars: the transformation of its navy into a blue-water force; the army’s novel expeditionary capabilities and capacity to sustain the deployment of proxies; and, lastly, the establishment of forward operating bases across Turkey’s expanding sphere of influence. Using this toolbox and capitalizing on the lessons learned, it is adopting an increasingly aggressive and revisionist foreign policy posture[131]. In Turkey this is perceived as proof of ascendance to the status of a “great power”[132].

The Turkish government dreams of a revitalized Turkish sphere of influence projecting power across three continents[133]. The goal is to become a trans-regional power that will ally itself on a case-by-case basis with whomever can offer it the most. Its aim is to reclaim its historic role as the regulating actor, so as its power grows, so will its negotiating leverage and level of autonomy. In a post-ideological and “transactional” international system, the higher the value of Ankara’s cooperation, the higher the price the West will have to pay for it. Turkey wishes to negotiate with the great powers as an equal, as it did in the heyday of the Ottoman Empire[134].

Turkey was never a genuine part of the West politically, culturally, or (with the exception of the Cold War) geopolitically.

The founding fathers of modern Turkey sought to build a republic that held up Western modernity as a model. The current government, which can trace its roots back to the radical right-wing dissidents who rejected this tradition, is seeking to achieve the reverse: the West is now an anti-model, a rival to be mirrored and eventually overcome[135]. After all, Turkey was never a genuine part of the West politically, culturally, or (with the exception of the Cold War) geopolitically. Its many identities, both real and imagined, coexist and are instrumentalized as necessary: To the West, Turkey presents itself as a bulwark against Russia. With Russia, it is part of Eurasia. In North Africa and the Middle East, it focuses on its Islamic role. In Central Asia, it highlights the significance of its Turkic heritage. In the Balkans, it places the Ottoman past center stage. In Africa, it has an Islamic and anti-colonial focus. It even adopts specifically anti-Western rhetoric in promoting itself as the protector of the weak and marginalized – all on a case-by-case basis, and all at the same time. Regardless of these contradictions, by instrumentalizing these different identities, Turkey is seeking to increase its influence on a transregional and even global scale.

Nevertheless, nationalism and the quest for strategic autonomy have cut across these ideological divides, regardless of how fringe or mainstream they may be.

Mirroring its different identities, loosely articulated and ill-defined ideologies (Kemalism, Eurasianism, neo-Ottomanism, Pan-Islamism, Pan-Turkism, etc.) also coexist within Turkey. Nevertheless, nationalism and the quest for strategic autonomy have cut across these ideological divides, regardless of how fringe or mainstream they may be. Nationalism is deeply ingrained in Turkish society, permeating diverse political parties and all levels of bureaucracy. Foreign Minister Çavuşoğlu expressed the prevailing mindset declaring: “Let’s not forget, there’s a bigger Turkey than our country.That’s the reason why we cannot be trapped in our borders. A significant part of the Turkish public appears receptive to irredentist rhetoric, with 56% of Turks agreeing that certain territories beyond Turkey’s borders should actually belong to Turkey[136]. President Erdoğan’s government and media have dedicated the past 20 years to spreading anti-Western conspiracy theories that paint Western allies as evil powers, attempting to sow discord to maintain their economic hegemony[137]. Turkey has long nurtured competing strains of anti-Western, anti-imperialist and anti-American thought[138], but the rhetoric of the current government has sent anti-Western and anti-American sentiment among Turkish people to record heights, with surveys indicating that most people in Turkey describe themselves as “anti-American.[139]” It is no surprise then, that when asked whom they held responsible for the war in a survey conducted by the Turkish pollster Metropoll, nearly half the respondents blamed the US and NATO and only 33.75% Moscow[140].

As a result, armed interventions will continue to be an attractive option for an increasingly confident bureaucratic elite.

The political leadership’s anti-West rhetoric and the anti-West tenor of public opinion feed into each other, as domestic and foreign policies are intrinsically linked. Therefore, no substantial change of course is likely in such a context, even if there is a change of administration, as the factors underpinning Turkey’s aggressive policies would still be in place[141]. Furthermore the Turkish bureaucracy’s security-oriented mindset, coupled with a context of regional crises, instability and power vacuums, plus a population receptive to military interventions, delimit certain tendencies within which Turkish foreign policy can be expected to operate. As a result, armed interventions will continue to be an attractive option for an increasingly confident bureaucratic elite[142].

Turkey envisages itself as a pivotal power – an indispensable partner with whom Washington, Moscow, or even Beijing can achieve effective agreements in the region.

Ankara’s emboldened politico-bureaucratic class perceives international relations in a completely transactional fashion[143]. One of the Turkish ruling elites’ central assumptions about the international system is that it is no longer West-centric, but post-Western. This reading views the global order as destined to become multipolar, which in turn provides regional powers with more room to maneuver. From this perspective, Turkish interests will be better served through a geopolitical balancing act between different centers of power[144]. Turkey envisages itself as a pivotal power – an indispensable partner with whom Washington, Moscow, or even Beijing can achieve effective agreements in the region.

Ankara is ultimately seeking to rebalance its position in the evolving world order. Since it perceived the world order as being in a transitional post-Western phase, and is negatively disposed toward a liberal word order, it is no surprise that Turkey’s current policy resembles its “Active Neutrality[145]” during World War Two, in which Ankara made overtures to both the Allies and the Axis and positioned itself to be on the winning side[146]. In what is seen as an increasingly multi-polar world, the Turkish government has improved its relations with Russia, Iran and China[147]. Sitting on the fence, whenever issues arise with Russia it relies on NATO protection. Whenever the West becomes a cause for concern, it threatens to strengthen its ties with Russia. And when its interests diverge from those of its NATO allies and the EU, Turkey adopts unilateral diplomatic and military initiatives[148].

Turkey wants to increase its relative power vis-à-vis the “West” in order to bargain with it on an equal footing, without cutting ties in any decisive way.

Turkey wants to increase its relative power vis-à-vis the “West” in order to bargain with it on an equal footing, without cutting ties in any decisive way. NATO used to be, and to some extent still is, the cornerstone of Turkish security, but Ankara is increasingly using the alliance in a cynical and self-serving way. It has used its membership to maximize its geopolitical influence and settle bilateral scores to the detriment of Cooperative Security[149]. The collective security guarantee backstops its foreign policy choices, shielding it from both direct Russian aggression and Western anger at its independent foreign policy choices[150]. In essence, Turkey has the luxury of fence-sitting precisely because of its NATO membership.

NATO’s mission, however, is to safeguard a liberal world order. Henry Kissinger summed up that vision as “an inexorably expanding cooperative order of states observing common rules and norms, embracing liberal economic systems, forswearing territorial conquest, respecting national sovereignty, and adopting participatory and democratic systems of governance”[151]. Turkey does not seem to subscribe to this; indeed, its quest for strategic autonomy, paired with its transactional mentality, actually undermines that vision.

Exploiting this strategic leeway, the “Blue Homeland” doctrine forms the crux of Turkey’s transregional bid for strategic autonomy.

Exploiting this strategic leeway, the “Blue Homeland” doctrine forms the crux of Turkey’s transregional bid for strategic autonomy. It is through this doctrine that Ankara seeks to dominate the Eastern Mediterranean, the mandatory point of passage for trade routes linking Europe to the Indian Ocean and, by extension, the markets of Southeast Asia[152]. By controlling the sea routes from the Black Sea and the Suez Canal to the Central Mediterranean, Turkey would control the major eastern transit pathways to Europe and become the undisputable trans-regional power.

Understanding the “Blue Homeland” as the heart of Turkey’s quest for strategic autonomy explains why Ankara remains an intransigently belligerent actor in the Eastern Mediterranean, while displaying flexibility in other diplomatic fronts.

Understanding the “Blue Homeland” as the heart of Turkey’s quest for strategic autonomy explains why Ankara remains an intransigently belligerent actor in the Eastern Mediterranean, while displaying flexibility in other diplomatic fronts. Over the past year, Turkey has restarted the reconciliation process with Armenia, while making courteous overtures to former adversaries across the Middle East: the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Israel being notable examples[153], all of which it formerly perceived to a greater or lesser degree as “occasional adversaries”[154]. At the same time, provocations against Greece and Cyprus, which it perceives as “structural adversaries”, continue to spike[155] in the shadow of the war in Ukraine. To quote Ryan Gingeras, Turkey expert in the Department of National Security Affairs at the US Naval Postgraduate School: “Erdoğan’s revisionist tendencies are best exemplified by his support for the creation of a large “Blue Homeland” in the Eastern Mediterranean. If he was to have his way, Greek sovereignty over its islands and waterways would be all but nullified[156].”

Fig. 4: Statement by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs regarding Turkish revisionism in the period 1973-2022 – Depiction in 16 maps (Source: Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Hellenic Republic)

Considering Ankara’s transactional mentality, the fruition of this project would entail major risks for the West. Firstly, all energy transit routes to Europe would be under Russian and Turkish control. Taking into account Turkey’s latest geopolitical success with Azerbaijan’s victory in Nagorno-Karabakh, an alternative westwards transportation route for Central Asian energy exports (and for China’s Belt and Road initiative) would bypass both Russia and Iran, further increasing Turkish leverage in a period when Russia-West relations are at a historic low[157]. At the same time, Turkey’s increased influence in the Caspian and Central Asia draws Ankara closer to Beijing, further increasing Turkey’s leverage over the West. Secondly, by pursuing control of the Eastern Aegean (and demanding the demilitarization of Greek islands), Turkey alone would be able to control the movement of the Russian fleet from the Black Sea to the Eastern Mediterranean and vice versa. This would increase Turkish leverage over both the West and Russia. Lastly, Turkey would have full control over migration flows to Europe from the Eastern and Central Mediterranean, exerting hybrid pressure at will.

In a globalized and interconnected world, Turkey’s actions in the Eastern Mediterranean could “legitimize” China’s corresponding actions in the Pacific, further undermining the international legal order.

The dangerous precedent set by Turkey’s “Blue Homeland” could also reverberate across the world, fomenting instability in other maritime flashpoints. Ankara’s project increasingly resembles China’s “nine-dash line”, which encompasses almost all of the South China Sea, both in its maximalist claims and its disregard for the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLoS). In a globalized and interconnected world, Turkey’s actions in the Eastern Mediterranean could “legitimize” China’s corresponding actions in the Pacific, further undermining the international legal order.

Only strong and concerted political pressure from the EU and the U.S. can elicit Turkish compliance.

While regional cooperation should not proceed by excluding Turkey, it is also clear that such cooperation can only proceed on the basis of common international rules and norms. Like every other littoral state in the Eastern Mediterranean, Turkey has legitimate interests which are defined by international law. Turkey’s compliance with UNCLOS could pave the way for the delimitation of maritime zones in the Eastern Mediterranean, which could trigger stronger and more effective regional cooperation to the benefit of every littoral state as well as of Western alliances. Currently, attitudes prevalent among Turkey’s political class and bureaucratic elites prohibit such an outcome. Only strong and concerted political pressure from the EU and the U.S. can elicit Turkish compliance. And for this to happen, a lawful and mutually acceptable solution to the Cyprus problem remains a prerequisite.

“Europe cannot afford to be a bystander in a world order that is mainly shaped by others”, reads the executive summary of the E.U.’s Strategic Compass draft[158]. If Turkey manages to impose the legal and geopolitical doctrine of the “Blue Homeland”, that is precisely the future we will be facing.

[1] Manoli, P. (2021, January 27). Economic linkages across the Mediterranean: Trends on trade, investments and Energy. Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP). Retrieved February 27, 2022, from https://www.eliamep.gr/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Policy-paper-52-Manoli-final.pdf

[2] Gürcan, E. C. (2020). A neo-mahanian reading of Turkey and China’s changing maritime geopolitics. Belt & Road Initiative Quarterly (BRIQ). Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://briqjournal.com/en/neo-mahanian-reading-turkey-and-chinas-changing-maritime-geopolitics

[3] Sukkarieh, M. (2021, March 1). The East Mediterranean Gas Forum: Regional Cooperation amid conflicting interests. Natural Resource Governance Institute. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://resourcegovernance.org/analysis-tools/publications/east-mediterranean-gas-forum-regional-cooperation-amid-conflicting

[4] Novo, A. R. (2021, March 29). The eastern Mediterranean – time for the U.S. to get serious. Center for European Policy Analysis. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://cepa.org/the-eastern-mediterranean-time-for-the-u-s-to-get-serious/

[5] Chaziza, M. (2021, December 22). Cyprus: The next stop of China’s belt and road initiative. The Diplomat. Retrieved March 3, 2022, from https://thediplomat.com/2021/12/cyprus-the-next-stop-of-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative/

[6] Dalay, G. (2021, August 4) Turkish-Russian Relations in Light of Recent Conflicts. German Institute for International and Security Affairs. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/turkish-russian-relations-in-light-of-recent-conflicts#hd-d17741e177

[7] Kardaş, Ş. (2020, August 13). Understanding Turkey’s coercive diplomacy. German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF). Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.gmfus.org/news/understanding-turkeys-coercive-diplomacy

[8] Tsakonas, P. (2021, April 5). Turkey: A problem partner? Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP). Retrieved April 15, 2022, from https://www.eliamep.gr/en/publication/turkey-a-problem-partner/

[9] Tekines, M. H. (2021, December 8). What would a post-Erdoğan Turkish foreign policy look like? War on the Rocks. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://warontherocks.com/2021/12/what-would-a-post-Erdoğan-turkish-foreign-policy-look-like/

[10] Kamaras, A. (2021, March 5). Turkish drones, Greek challenges. Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP). Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://www.eliamep.gr/en/publication/drones-

[11] Hofman, L. (2020, December 10). How Turkey became a drone power (and what that tells us about the future of warfare). The Correspondent. Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://thecorrespondent.com/832/how-turkey-became-a-drone-power-and-what-that-tells-us-about-the-future-of-warfare/110071049088-d67e839e

[12] Siccardi, F. (2021, September 14). How Syria changed Turkey’s foreign policy. Carnegie Europe. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/09/14/how-syria-changed-turkey-s-foreign-policy-pub-85301

[13] Nedos, V. (2022, January 27). The Rafale and the balance of power in the Aegean (Τα Rafale και η ισορροπία δυνάμεων στο Αιγαίο). Kathimerini. Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://www.kathimerini.gr/politics/foreign-policy/561681280/ta-rafale-kai-i-isorropia-dynameon-sto-aigaio/

[14] Kabalan, M. (2019, February 16). Can the Astana process survive the US withdrawal from Syria? Al Jazeera. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2019/2/16/can-the-astana-process-survive-the-us-withdrawal-from-syria

[15] Duran, B. (2021, June 25). What does the second Berlin Conference mean for Libya? Daily Sabah. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.dailysabah.com/opinion/columns/what-does-the-second-berlin-conference-mean-for-libya

[16] Siccardi, F. (2021, September 14). How Syria changed Turkey’s foreign policy. Carnegie Europe. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://carnegieeurope.eu/2021/09/14/how-syria-changed-turkey-s-foreign-policy-pub-85301

[17] Tsakonas, P. (2021, April 5). Turkey: A problem partner? Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP). Retrieved April 15, 2022, from https://www.eliamep.gr/en/publication/turkey-a-problem-partner/

[18] Hamilton, R. E., & Mikulska, A. (2021, June 22). Cooperation, competition, and compartmentalization: Russian-Turkish relations and their implications for the West. Foreign Policy Research Institute. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.fpri.org/article/2021/04/cooperation-competition-and-compartmentalization-russian-turkish-relations-and-their-implications-for-the-west/

[19] Grigoriadis, I., & Gheorghe E. (2022, May 20). The Akkuyu NPP and Russian-Turkish Nuclear Cooperation: Asymmetries and risks. Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP). Retrieved May 26, 2022, from https://www.eliamep.gr/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Policy-paper-100-Grigoriadis-and-Gheorghe-.pdf

[20] Mankoff, J. (2022, January 13). Turkey could lose big in the Russia-Ukraine standoff. Foreign Policy. Retrieved March 3, 2022, from https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/01/13/turkey-russia-ukraine-conflict-military-nato/

[21] Mankoff, J. (2022, January 20). Regional competition and the future of Russia-Turkey relations: A World Safe for Empire? Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.csis.org/analysis/regional-competition-and-future-russia-turkey-relations

[22] Danforth, N. (2020, December 11). Perspectives: What did Turkey gain from the Armenia-Azerbaijan War? Eurasianet. Retrieved May 17, 2022, from https://eurasianet.org/perspectives-what-did-turkey-gain-from-the-armenia-azerbaijan-war

[23] Bechev, D., Saari, S., & Secrieru, S. (2021, June 24). Fire and Ice. European Union Institute for Security Studies. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/fire-and-ice

[24] Ibid.

[25] Diakopoulos, A. (2022, February 8). Ukraine and Russia’s complex relationship with Turkey. eKathimerini.com. Retrieved February 28, 2022, from https://www.ekathimerini.com/opinion/1177080/ukraine-and-russias-complex-relationship-with- turkey/