This paper explores the digitalization of diplomacy and attempts to shed light on the adaptation level of the European Union by presenting the European External Action Service’s activity on social media and selected Public Diplomacy initiatives during the covid-19 pandemic. The main research questions posed in the study are: a) in what ways has the European Union used digital tools to respond to the coronavirus crisis; and b) what are the (recurring) challenges facing the European Union in its efforts to improve its image in a changing world and enhance its role as a leading global actor? The paper concludes that while the European Union is highly competent in terms of digitalization, it does face challenges, which are partly inherent in the sui generis nature of the European Union as an International Organization. These include the need for deeper integration, better coordination between member states, and further dialogue with the Union’s citizens, and must be met if the EU is to enhance trust and build solidarity, as well as a clearer and more solid European identity.

Read here in pdf the Policy paper by Christos A. Frangonikolopoulos, Professor of International Relations & Communication, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Jean Monnet Chair in EU Public Diplomacy (2020–23) and Eleftheria Spiliotakopoulou, Public Diplomacy Officer at the Hellenic Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Introduction

In terms of technological development, many sectors had already undergone a digital transformation in the pre-covid era. This was the case with diplomacy in recent years, as it became increasingly clear that the Internet and other information technologies would cease to be peripheral in the conducting of world affairs. Still, there can be no doubt that the pandemic is accelerating digital change and amplifying the adoption of new technologies, which may have a long-lasting impact beyond Covid-19.

Having triggered a profound change in the way diplomacy is conducted, 2020 may well be remembered as the year of digital resurgence.

This was made clear at the very beginning of the pandemic: as the coronavirus went viral, diplomacy went virtual[1], with Ministries of Foreign Affairs (henceforth: MFAs) and International Organizations (henceforth: IOs) moving from conference rooms to online spaces, which would have been unimaginable until very recently. Having triggered a profound change in the way diplomacy is conducted, 2020 may well be remembered as the year of digital resurgence[2]. On a second level, taking it into consideration that crisis management is not only a question of action but also of perceptions, the need to transition from onsite to online goes beyond meetings and conferences. In fact, crises offer opportunities for diplomatic actors who are looking to manage their image. Thus, Public Diplomacy (henceforth: PD)—namely the means by which a state or an IO communicates with publics for the purpose of advancing its policy goals—must also be re-evaluated and re-shaped accordingly.

Traditionally, PD refers to processes by which countries seek to accomplish their foreign policy goals by communicating with foreign publics. It is also a tool for creating a positive climate among foreign populations in order to facilitate the acceptance of one’s policies. PD consists of five main components: i) listening, ii) advocacy, iii) cultural diplomacy, iv) exchange diplomacy and v) international broadcasting[3]. Scholars had already introduced the term “New PD” (henceforth: NPD) by the turn of the 21st century, which represents an attempt to adjust PD to the conditions of the Internet-driven Information Age. Even though the aim of managing the international environment remains the same, there some key shifts in the practice of NPD, including: the increasing involvement of non-state actors (NGOs, citizens etc.), the use of real-time technologies (especially the Internet), the blurring of domestic and international news spheres, the adoption of strategies based on nation branding and network communication theory, the increasing use of terms like soft power in place of prestige, and an emphasis on the active role played by publics and people-to-people contact.

The coronavirus crisis necessitates a new focus on NPD, as it forces diplomatic institutions to better exploit the benefits of digitalization which is actually more than a purely technological shift.

The coronavirus crisis necessitates a new focus on NPD, as it forces diplomatic institutions to better exploit the benefits of digitalization, which is actually more than a purely technological shift. There seem to be two schools of thoughts regarding Digital Diplomacy: the first claims that it is a new tool in the conducting of PD; the second maintains that it increases the ability to interact with foreign publics and actively engage with them thereby enabling the transition from monologue to dialogue. This may explain the fractured terminology encountered in NPD studies, where several terms are employed interchangeably. Thus, while some focus more on the conceptualization of diplomacy in the Digital Age, others emphasize characteristics of digital technologies or attributes of contemporary society: examples include Digital Diplomacy (henceforth: DD), Netpolitik, Network Diplomacy, and Twiplomacy. So perhaps the way to understanding the digitalization of PD would be to merge the two perspectives and approach it as the growing use of ICTs and social media platforms by countries or IOs seeking to achieve their foreign policy goals and practice PD thereby.

In addition, and taking into consideration that diplomacy is a social institution, the digitalization of diplomacy is a long-term process that does more than offer new functionalities and actually promotes new norms—such as increased openness and transparency, dialogue, collaboration and network mentality—which impact in turn on every dimension of diplomacy: audiences, institutions, practitioners, and the practice of diplomacy itself. As rightly suggested[4], one should not separate diplomats into those that are digital and those that are not. Diplomats, foreign ministers, foreign ministries, embassies and international organizations are all undergoing a process of digitalization, continuously embracing new tools and platforms as they reimagine the environment in which diplomacy is practiced. This process not only influences the manner in which diplomats, politicians, foreign ministers and foreign ministries understand and envision the world, it also impacts on the habits of their audiences, the actors with whom they seek to engage, and the technologies they employ to achieve their goals.

Digitalization is a process that influences the practice of PD on three levels:

- The institutional level: digital technologies facilitate and contribute to the adoption of new norms and beliefs (“dialogue” and interaction with online publics, “listening” and feedback from online publics, the “incorporation” of such feedback into policy formulation).

- The practitioner level: digital technologies allow diplomats to engage with a plethora of new actors both online and offline. This leads to greater openness and the increased agency of non-state actors (i.e., online publics, civil society organizations, NGOs), but also changes diplomatic behavior through the formation of temporary alliances (or networks) to advance specific goals (protection of human rights, policies to deal with climate crisis).

- The audience level: PD practitioners will use online technologies to communicate with their peers and audiences as well as their family and friends. This both cultivates a sharing mentality and contributes to more transparency in PD practices.

Given the potential of Social Networking Sites (SNS), the Web and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) to foster dialogue and two-way symmetrical communication with online publics, the digitalization of PD may in itself equate to the manifestation of NPD and the democratization of diplomacy. Power actually resides in the networks that have become the matrix, or else the foundation, of our society. As a result, those who succeed in this new world of complexity need to become part of the underlying operational aspects of the network they are trying to affect–that is, they need to embrace the capabilities of modern networks and become a major hub by influencing the influencers, promoting authentic and compelling narratives, and engaging in dialogue.

Diplomats had already taken on board the need to adapt to this new media ecology in the pre-covid era. Βy 2016, for instance, 170 MFAs had created their own websites through which they communicated with the public[5], and by 2018, 97% of the governments and leaders of the 193 UN member states had an official presence on Twitter, including 131 MFAs, 107 foreign ministers, more than 4,600 embassies, and 1,400 ambassadors[6]. Empirical research shows that the majority of MFAs have not as yet realized the full potential of DD, as SNS are still mostly used as tools for top-down, state-centric, one-way communication rather than a platform for dialogue and collaboration with non-state actors[7]. It is clear, therefore, that even though we have moved a long way from old towards NPD, the latter is still underperforming in practice. With that in mind, in the light of the coronavirus pandemic and the challenges it posed to diplomatic institutions, including IOs such as the EU, this article addresses the need to refocus PD in relation to action and reputation management.

EU digitalization of public diplomacy

Just like most states and IOs, the EU has eagerly adopted SNS over the past decade. This is an important development for the democratization of the EU, as SNS can render IO bureaucracies– which can be perceived as rather obscure and impenetrable–more visible and “sociable” on the global digital stage[8]. Even though the EU’s DD apparatus amounts to an empire of SNS accounts, the most “representative” of these—in terms of PD–would be the account of the EU diplomatic service: the European External Action Service (henceforth: EEAS). The EEAS was officially launched on 1 January 2011, giving the EU a unique opportunity to shape a successful PD and address concerns about the visibility, efficiency and coherence of EU action in the world by centralizing the different PD components of the EU’s external relations in a single integrated structure, headed by the EU’s Higher Representative. That the launch of the EEAS was accompanied by DD ambitions was reflected in its official Twitter account (entitled “EU External Action” / account name @eu_eeas), which was created as early as October 2009, before the Lisbon Treaty had entered into force, and in effect predated the launch of the EEAS by more than a year. In fact, SNS were identified and anticipated from the very start as a tool for achieving the EEAS’s task of strengthening the EU’s PD.

Almost all Delegations have a Facebook presence, and more than three out of four EU Delegations have a Twitter account.

Also indicative of the importance attributed to DD is the fact that, while the EEAS’s SNS channels were managed by two people in 2011, six years later, the Strategic Communications Division of the EU’s diplomatic service had grown substantially to a staff of 51 persons (Hedling 2018). Moreover, the Strategic Communications team now covers languages ranging from Arabic to Armenian[9]. In fact, apart from the EEAS’s main accounts on five SNS (Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Flickr, You Tube), the Service is also present on many more (such as Weibo and Vimeo) thanks to the work of the 143 EU Delegations and 17 Missions and Operations on the ground. Engaging on SNS in local languages has become a best practice among all Delegations, indicating that the Service has realized the value of tailor-made/personalized diplomacy in accordance with the latest trends in NPD. Research indicates that EU Delegations have been fairly effective in adapting to the “new” PD practices, focusing on dialogue rather than on one-way communication and using a broad range of communication channels[10]. Almost all Delegations have a Facebook presence, and more than three out of four EU Delegations have a Twitter account. In some host countries, surveys have indicated that more than half the population uses social media as a primary source for their information on the EU. This is why social media platforms are an important pillar for PD.

In terms of DD performance, according to Manor’s analysis[11] of MFA social networking, which includes the EEAS’ SNS presence, the EU scores the third highest score on the “in-degree” parameter, since it is followed by 38 other MFAs (out of a sample of 69 ministries). This is an important parameter, as the greater an MFA’s popularity within the network, the greater its ability to disseminate information to other MFAs. As far as the “out-degree” parameter is concerned, which relates to the extent to which an MFA follows its peers on Twitter, the EU scores the sixth highest score as it follows 41 of the 69 MFAs on the network. This is also an important parameter, as the more other MFAs an MFA follows, the greater its ability to gather information on other nations’ foreign policy initiatives. The final parameter is the “betweenness” parameter, which reveals which MFAs serve as important information hubs by linking together ministries that do not follow each other directly. The EU achieves the highest score on this parameter, indicating that it is the most important information hub in the social network of MFAs and serves as a crucial “Twiplomatic” link. Overall, the EEAS is in the top five of MFAs that score highly on all three parameters. According to the Twiplomacy Study (2018), the EEAS is among the best-connected foreign offices in the world, being ranked in first place in 2018 (mutually following 132 MFAs and world leaders) and second place in 2020 (mutually following 145 MFAs and world leaders).

The initial engagement of multiple EU institutions with the crisis was a fine example of a coherent, clear and policy-orientated message having a significant impact on the evolution of the crisis.

This development, combined with the creation of a Strategic Communications Division within EEAS, the reinforcement of EU Delegations and EU Special Representatives with EU public diplomacy officers charged with organizing and conducting public diplomacy activities abroad, and the publication of both an Information and Communication Handbook for EU Delegations and the EU Global Strategy in 2016 (in which, for the first time, public diplomacy is described as a major tool in the implementation of Strategic Communications around the world) have reinforced the status of public diplomacy within the EU architecture and significantly improved its implementation in the field. This was made clear by the Evros Crisis in 2020. The initial engagement of multiple EU institutions with the crisis was a fine example of a coherent, clear and policy-orientated message having a significant impact on the evolution of the crisis. It was a marked contrast from the recent cacophonies and delays in decision making by European institutions (debt and refugee crises), which had severely damaged the EU’s institutional reputation, and demonstrated that the EU possessed the three necessary preconditions of actorness in world affairs: opportunity, presence and capability. The EU’s coherent and determined response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine is another example.

Research findings

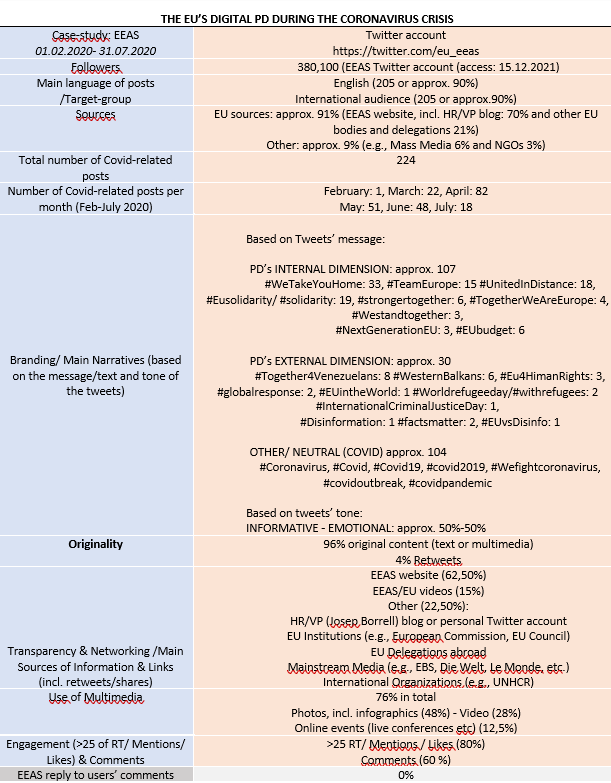

In order to assess the EU’s digital PD during the coronavirus crisis, this article contributes an empirical study of mediatization based on an analysis of the online/social media activity of the EU’s diplomatic service (EEAS) over a period of six months from February 2020, when the crisis was breaking out across Europe, until the end of July 2020, when the EU struck a deal on a post-coronavirus recovery package. Overall, 224 covid-related tweets are examined, including tweets that are indirectly connected to the subject (e.g., that refer to the coronavirus in the tweet’s link in relation to another issue or digital initiative, such as virtual events, online surveys or quizzes that would probably be conducted in person rather than online, if it were not for Covid-19)[12].

The research findings—presented in the table below—are further analyzed through the conceptual lens of NPD and the following questions:

Q1: Has the EU exploited the benefits of digitalization?

Q2: Ιn what ways did the EEAS in particular respond to the digital and pandemic-driven challenges in the context of NPD?

Q3. Has the EU managed its image as a resilient power in an ever-changing world, and what are the recurring challenges it must confront if it is to improve its reputation and enhance its role as a leading global actor?

Digital readiness, information transparency and real-time responsiveness

At the start of the crisis, many governments had still to embrace the new tools, perhaps because of IT infrastructure difficulties or due to nervousness about confidentiality. Others remained reluctant to set aside the diplomatic protocols and rules of procedure appropriate to a non-digital era. According to a UN survey, more than 40% of countries had no information about Covid-19 on their websites at the end of March 2020. More specifically, a review of the national portals of the 193 UN member states showed that by 25 March 2020, 57 per cent (110 countries) had put in place some kind of information on Covid-19, while around 43 per cent (83 countries) had not provided any information. However, a further analysis showed that by 8 April 2020, around 86 percent (167 countries) had included information and guidance about Covid-19 on their portals[13].

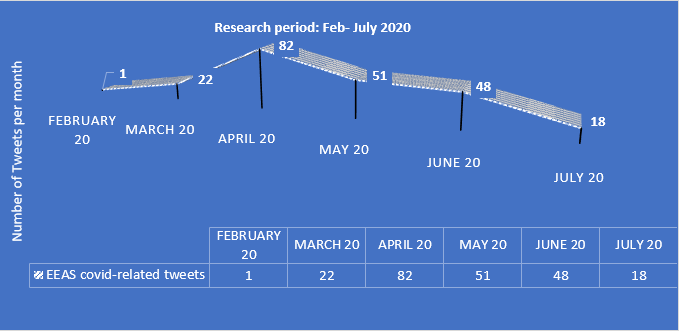

In terms of the EEAS’ digital/real-time responsiveness, as early as 25 February 2020, a tweet it posted redirected to a press release published on the EEAS website under the title “EU leads global efforts against Covid-19”. Interestingly, this date coincides with the European Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stating that Covid -19 was heading towards pandemic status, while Italy was experiencing the disease’s biggest outbreak in Europe, with more than 260 cases and seven deaths reported. The second tweet was published on 12 March 2020, when the WHO declared Covid-19 a pandemic. It is important to note that only after this date does the EEAS start posting tweets on the issue on a more frequent basis, starting from 0.03 covid-related tweets on average per day in February, peaking in April 2020 with an average of 2.7 covid-related tweets per day, before dropping slowly but steadily to 0.6 covid-related tweets per day in July 2020, as the crisis gradually de-escalated in conjunction with the completion of citizen repatriation and, finally, the EU leaders’ agreement on the recovery plan for Europe on 21 July 2020.

EEAS covid-related tweets – quantative analysis

Thus, as indicated in the above graphic, the total number of covid-related tweets posted per month (February: 1, March: 22, April: 82, May: 51, June: 48, July: 18) closely mirrors the typical cycle of communication during a crisis: warning–risk assessment—response-management—resolution—recovery[14]. However, even though the EEAS’ digital response can be evaluated as satisfactory in the context of the aforementioned UN survey findings, it could still have done better at addressing the issue in the initial phases of the crisis (warning—risk assessment). In this context, it is worth mentioning that, according to an analysis based on data from Twitter across a number of European countries, unexpected levels of concern about pneumonia had been raised for several weeks before the first cases of infection were officially announced[15].

Moreover, when it comes to crisis response and management, it is noteworthy that the EEAS still had not addressed the Corona issue on Twitter, even during the first week of the outbreak in Europe. Given that the outbreak in Italy was just starting, the one tweet it published that week (on February 25) dealt with China and emphasized foreign aid rather than a coordinated EU response. The EEAS is, of course, hampered in its digital communications by the need to seek approval from the member states before addressing a given subject online. Moreover, the EU does not dictate national policies, nor can it publish its own health guidelines, as the latter are formulated by national governments.

Real-time diplomacy could be considered the EU’s Achilles heel and a factor that jeopardizes its ability to reap the benefits of digital PD.

Given this context, real-time diplomacy could be considered the EU’s Achilles heel and a factor that jeopardizes its ability to reap the benefits of digital PD. However, even though the independence of IOs is constrained by design, since it is the states that create, support and direct them, the power IOs wield can take different forms, though it is typically not direct. IOs cannot impose their will or rules on other international actors; instead, they tend to act as “orchestrators” by projecting inter alia a unique and coherent identity which they develop by building a narrative centered on who they are and what they represent. With that in mind, we shall now proceed to analyze how the EEAS sought to (re)shape EU identity during the Covid-19 pandemic crisis.

“Europe United in Distance”: EU branding efforts amidst a global battle of narratives

Given that Covid-19 was an unprecedented health, social and political crisis, the success with governments and countries manage it has become a prestige issue. In addition, in the wake of the crisis, the narratives developed to guide citizens and make sense of these uncertain times are as important as the actual success of the plans implemented. The largest deployment of PD motivated by the Covid-19 crisis took place at the highest level of world leadership. In the United States, President Trump started a blame game by using the “Chinese virus” label with the intention of discrediting China with regard to the origin of the pandemic and the lack of transparency in the initial phase of the pandemic outbreak. Beijing’s diplomacy, on the other hand, sought to turn the situation around by providing sanitary material to a significant number of countries, thus presenting China as a champion of solidarity[16]. In fact, on 13 March 2020, China led a videoconference with 17 European countries from Central and Eastern Europe to advise them on how to fight the virus; the Chinese also promised material help, with a Chinese plane loaded with medical supplies and experts arriving in Italy in March 2020. But while, for the European Commission, China’s kind gestures were just a way of thanking those EU countries that had provided it with significant assistance when it was the epicenter of the coronavirus crisis some weeks earlier, for China itself, this “mask” diplomacy was an instrument of soft power: its narratives were designed to counter what was perceived as Western hostility, and sought to discredit European states by pointing to and exaggerating their difficulties in combating the epidemic and resolving the health crisis[17].

Seeing China’s PD vis-à-vis the EU as purely a short-term response to the Covid-19 crisis would be a mistake. Rather, it is part of a long-term strategy to consolidate the country’s power in the international system by attracting new allies. In this context, it is clear that there is both what HR Josep Borrell calls a “global battle of narratives” with “a geo-political component” taking place during the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak, and a “battle of narratives within Europe” in which “it is vital that the EU shows it is a Union that protects, and that solidarity is not an empty phrase”[18]. In fact, on Borrell’s initiative, during the first six months of the crisis, the EEAS responded to these challenges by publishing inter alia three special reports focused on combating foreign narratives and misinformation regarding Covid-19 on the “EUvsDisinfo” website[19], while the EEAS East Stratcom Task Force detected and exposed more than 550 disinformation narratives from pro-Kremlin sources[20].

Countering half-truths or fake news is of particular importance, as diplomatic institutions must deal with disinformation and propaganda if they are to practice PD online effectively.

Countering half-truths or fake news is of particular importance, as diplomatic institutions must deal with disinformation and propaganda if they are to practice PD online effectively. Countering disinformation and propaganda can also be seen as contributing to the EU’s identity building, as it is based on standard statements about the EU being “a zone of peace, prosperity and democracy” functioning as a “model” that respects “the rule of law and good governance”. Moreover, the friction over access to health materials experienced by some EU member states in the early days of the pandemic was a key factor in the EU emphasizing the discourse and provision of solidarity and viewing the crisis as an opportunity to improve the situation along with its governance of international affairs.

It is important to bear in mind that, even though the Covid-19 pandemic was an external crisis which affected all states and IOs equally, it nonetheless posed a great challenge to the identity of the EU. The EU often seems to be operating in a context of recurring existential crises: from the 1965 Empty Chair to the eurozone and refugee crisis of 2015, doomsday scenarios about “the end of Europe” have often prevailed. And yet none of these predictions have actually come true[21]; on the contrary, “resilience”, understood as “the ability of states and societies to reform, thus withstanding and recovering from internal and external crisis”, is the new leitmotif of the EU’s Global Strategy (2016).

The tweets’ key messages and hashtags reflect the fact that the EEAS used framing to brand the EU as a resilient power over time, and as a reliable and robust partner for EU and non-EU citizens alike.

Thus, it comes as no surprise that this paper should have found that the tweets’ key messages and hashtags reflect the fact that the EEAS used framing to brand the EU as a resilient power over time, and as a reliable and robust partner for EU and non-EU citizens alike. Even more interesting, perhaps, is how the EEAS focused more on the domestic dimension of the EU’s PD during the first phase of the covid outbreak. More specifically, looking at the message, hashtags and tone of the EEAS tweets, the key message of solidarity is expressed 50 percent of the tweets via hashtags such as #WeTakeYouHome, #UnitedInDistance, #TeamEurope, #Eusolidarity/#solidarity, #strongertogether, #TogetherWeAreEurope, #Westandtogether, etc. The tone is emotional and the language used is that of unity, solidarity and team spirit; it is the language of “We”. Hashtags focusing solely on the international dimension of the EU’s PD (such as #Together4Venezuelans, #WesternBalkans, #Eu4HimanRights, #globalresponse, #EUintheWorld, #Worldrefugeeday/#withrefugees, #InternationalCriminalJusticeDay) represent only 15 percent of the total number of tweets analyzed. Other than that, there are tweets with a more informative tone and neutral hashtags (including the word “covid”), which can either be combined with the above sub-categories or sub-categorized as “Other”.

It is also interesting to note that the EEAS used visuals to support the EU’s linguistic frames and narratives. More specifically, 76 percent of the tweets were accompanied by some kind of multimedia, with 48 percent including infographics and 28 percent videos. As pointed out in other PD case studies[22], images function to extend frames focused on the present to embrace broader narratives involving the past, present and future. This is evident in the case of the EU, which wishes to convey its message of solidarity to recipients both within and beyond its borders, as framed for instance in a video created by the EU Delegation in Cuba. Apart from covid- related facts and figures, the main message of the video is captured in the hashtags #EUsolidarity and #WeTakeYouHome, while EU Ambassador to Cuba Alberto Navarro states that “Solidarity is the value we share as Europeans […] what we need to build a better Europe and a safer world”[23]., This message of solidarity, as a key element in the EU’s norms and values, was promoted even more evidently on Europe Day, with a tweet which states that “Today more than ever, there is only one way to overcome major challenges in Europe and around the world—that way is solidarity”[24]. Overall, the results demonstrate that the EEAS used SNS to create a distinct brand for the EU during the Covid-19 outbreak, that of “Europe United in Distance”; this study thus echoes earlier research findings[25] about the EU’s PD on Twitter and the EEAS’ efforts to create a “Europe United” iBrand.

The fact that the EEAS focuses more on the internal dimension of the EU’s PD could be interpreted as an effort on the EU’s part to succeed in terms of consular crisis management and citizen repatriation during the initial phase of the pandemic. It could also indicate, given that its PD has evolved from an informational to a relational approach, that the EU has learned from previous, as well as the most recent, crises that successful PD starts at home. In fact, the permeability between “foreign” and “domestic”, coupled with an increasingly active civil society, is making a more holistic approach to public engagement a central element of any contemporary diplomacy[26]. This reveals the “intermestic” nature of EU PD, which is based on the hypothesis that the domestically constructed identity is exported and employed externally, while the domestic and international dimensions mutually reinforce one another.

Also important, in terms of PD and branding, is the effectiveness of this global battle of narratives during the Covid-19 outbreak, between China’s “mask” diplomacy and the EU’s narrative of solidarity, and the extent to which the crisis could be turned into an opportunity frame. One could say that China’s attempts to change the Covid-19 narrative in Europe met with success: take Serbia, for instance, and President Vučić’s statement that “European solidarity does not exist” and that “only China can help Serbia fight the virus”[27]. It is true that the EU dithered in its initial response to tackling Covid-19 and in coming to the aid of both member and non-member states. Still, it did provide Italy, for instance, with a ‘heartfelt apology’ for not coming to its aid earlier, and ultimately provided more aid to Serbia than China did[28] (Verma 2020). In addition, to understand the underlying dynamics of the EU-Serbia-China triangle, one needs to place Vučić’s statements in a broader context, as Serbia has not only experienced increased democratic backsliding and repression of the media/free speech in recent years, it has also attracted the highest amount of Chinese loans and investment among the six countries of the Western Balkans, making it Europe’s fourth-biggest recipient of Chinese foreign direct investment[29].

PD and crisis communication is not, and should not be, seen as merely a performative act. It calls for transparency. As the world is watching, national reputations and credibility are on the line and could suffer real and permanent damage[30]. In this context, various aspects of the Chinese initiative have underlined the limits of that nation’s PD and crisis management, first because some of the equipment sold by Chinese companies turned out to be defective, and second, because it proved counterproductive at a time when democracies were facing a health crisis. In fact, according to the Good Country Index, which is distinct from the Nation Brands Index in that it measures actual behavior rather than perceptions, China dropped from 23rd to 35th place, which is a long way to fall, especially when one considers that China has ranked 22nd, 23rd or 24th in every edition of the Index since 2008[31].

European solidarity is more than skin-deep. It varies by crisis type, with strong solidarity in case of exogenous shocks like a pandemic and weak solidarity in case of endogenously created problems such as, potentially, debt crises.

As for Europe and the discourse on solidarity, Europeans seem to be deeply interconnected despite divisions, unilateral travel restrictions and export bans, according to the European Solidarity Tracker[32], an interactive data tool that visualized solidarity among EU member states and institutions in the initial phase of the Covid-19 outbreak. According to the tool’s key findings, every member state has shown solidarity towards its fellow Europeans. Moreover, the EU institutions stepped up their response in financial and economic terms, but also when it comes to the people of Europe. Thus, the European Solidarity Tracker contradicts claims that the European project has failed. In fact, according to the Standard Eurobarometer survey conducted in June-July 2021, optimism about the future of the EU has reached its highest level (49%) since 2009, and trust in the EU remains at its highest since 2008 (36%). Nearly two-thirds of Europeans trust the EU to make the right decisions in the future in response to the pandemic[33]. However, the EU still has a way to go with regard to creating a sense of European citizenship and cohesiveness that could translate into a solid identity. According to a survey conducted by the European University Institute and YouGov (2020), solidarity is expressed nationally first, towards neighbors next, and only distantly European. Still, European solidarity is more than skin-deep. It varies by crisis type, with strong solidarity in case of exogenous shocks like a pandemic and weak solidarity in case of endogenously created problems such as, potentially, debt crises. By and large, European citizens view solidarity as a reciprocal benefit rather than a moral or identity-based obligation[34].

Networking and audience engagement

Digital PD increases diplomats’ ability to interact with foreign publics, thereby enabling the transition from one-way to two-way communication. From a procedural perspective, digital technologies give practitioners the opportunity to engage with a plethora of new actors both online and offline, and replace the perception of the exclusive club for that of the inclusive network. From a behavioral perspective, diplomatic actors now curate information for their followers, thereby ensuring the accuracy of the information delivered online.

Taking the above into consideration, our research also explored audience engagement in terms both of the content of the EEAS tweets (originality, transparency, language) and its dialogical nature (relevance, reach, comments). More specifically, according to the paper’s findings, almost all the posts on the EEAS’ main Twitter account are original (only 4 percent are retweets, and these are primarily of tweets published on HR Borrell’s and the European Commission’s accounts). The majority includes links to EU documents and official sources/websites (91 percent), with 69 percent linking to the EEAS website, on which SNS users can access additional information, conforming with the EU’s values and digital society’s norms of openness and transparency. Furthermore, most of the photos/infographics and videos are also original, as they are specially created by and for the EU. At this point, it is also worth reiterating that multimedia is used in 76 percent of the EEAS’ tweets in an effort to secure users’ attention. In terms of the language used to narrate the crisis, English (90 percent) was the main language, with German, French and Spanish also used. Using English as a “lingua franca” is in line with NPD practices as well as the EU’s role as an IO which needs to engage a large and diverse audience both within and beyond its borders.

At the same time, however, it is important to note that EEAS press releases—which in most cases (approximately 69 percent) are the tweets’ source—may be translated ad hoc into a local language, if the tweet’s message and target-group demand it. For example, a tweet published on the EEAS account promoting Albania as an example of EU solidarity (2 April 2020) was redirected to a press release on the Service’s website, which was also available in Albanian[35]. Similarly, tweets regarding EU aid to Nicaragua (8 June 2020) were redirecting to a video prepared by the EU Delegation in Nicaragua and a press release published on the EEAS website, both of which were available in both English and Spanish[36]. This indicates that the EEAS both strives to safeguard cultural diversity as a fundamental norm of the EU and realizes the value of tailor-made/personalized diplomacy, in accordance with the latest NPD trends.

The EU’s dependence on and investment in DD with a view to engaging with the media and the public during the coronavirus crisis is obvious in tweets referencing online events.

The EU’s dependence on and investment in DD with a view to engaging with the media and the public during the coronavirus crisis is obvious in tweets referencing online events that would otherwise have taken place in person. For instance, press conferences had to go online. Peter Stano, the lead spokesperson for the EEAS, shared a picture (March 2020) of the empty press conference room and the journalists calling in via video connection for the daily midday briefing[37]. In the same vein, according to this paper’s findings, 12.5 percent of EEAS tweets during the first six months of the Covid-19 outbreak related to live conferences and online events: from the FAC Press Conference and the virtual Med2020 Dialogue webinar to the Europe Open Doors event that had to be replaced with a specially designed video stating the following: “We couldn’t open our doors this time, so we opened our digital windows to take you on a trip around the world. Thanks for being with us on Europe Day 2020”[38].

The first and foundational way in which any international actor should engage a foreign public is by listening to that public.

However, audience engagement goes beyond providing information sources, using local languages, or organizing online press briefings and webinars. In fact, the first and foundational way in which any international actor should engage a foreign public is by listening to that public. In this context, the EEAS’ efforts to listen to, and build up relations with, the public are best reflected in the users’ feedback. According to the paper’s findings, 80 percent of the tweets received more than 25 reactions from the public (measured in likes, retweets and mentions), while 60 percent received a reaction in the form of users’ comments. Interestingly, the most engaging tweet of all narrated the EU as a peace project, connecting past, present and future in order to conclude that solidarity is the way to overcome major challenges in Europe; it was based on a video especially made for Europe Day[39]. At this point, it is worth mentioning that this tweet is one of the few (approximately 6 percent) EEAS tweets that received more than 200 reactions from the public—of these highly engaging tweets, 70 percent used video as multimedia. On the other hand, it is also worth mentioning that, according to our findings, 60 percent of those EEAS tweets that received less than 25 reactions (measured in likes, retweets and mentions) also used multimedia, thus indicating that posting multimedia may help, but should not be considered a rule or a necessary precondition for engaging with followers effectively on Twitter.

In terms of interactivity, special mention should be made of two surveys which asked users to assess the EEAS website, plus a knowledge quiz posted on Europe Day, as a way of “listening” to their views on the web experience and the EU in general[40]. In terms of network diplomacy, the picture is slightly better on the EEAS website, where selected PD initiatives are presented under the title #UnitedInDistance. The EEAS presents solidarity success stories from both within and beyond the EU which involve other actors, including individuals and NGOs[41]. However, only rarely is there an opportunity to engage in live dialogue or interact with the organizers or with other users directly. In fact, the only tweet which gave the public a chance to pose questions directly to an EU Ambassador was organized in the context of celebrations for Europe Day through a Facebook Live Chat[42]. In addition, the EEAS does not reply to any of the users’ comments. In terms of networking, 22.5 percent of the tweets mention other diplomatic actors as sources of information. Apart from other EU institutions, these include mainstream media and IOs, but not ordinary citizens, indicating that the elite world of foreign affairs is still alive and well in the Digital Age.

Discussion and Policy Recommendations

According to our findings, the EEAS adapted to the new virtual communication environment following the outbreak of the coronavirus crisis. In fact, it posted more than one covid-related tweet per day on average, while more than one out of ten tweets during the first six months of the crisis referred to covid-related live briefings, webinars and online events.

The EU may need to adopt new working practices and communications strategies that free up the EEAS and allow it to become an indispensable source of information for SNS users.

However, there is more to digitalization than simply a technological shift. Εven though the EEAS responded relatively promptly when it comes to posting information on Twitter about the coronavirus (February 25), it could still have done better when it came to taking into consideration the real-time events in Italy, which had already declared a state of emergency on January 31. The fact that EU policy statements and reactions to world events must be agreed upon by all member states has a detrimental effect on the EEAS’s ability to leverage Twitter for PD ends. To face this challenge, the EU may need to adopt new working practices and communications strategies that free up the EEAS and allow it to become an indispensable source of information for SNS users.

This challenge is also connected to a far more complex and sensitive issue, namely the need for better coordination between the PD of individual member states and of the EU. As the coronavirus spread, EU member states invested in national protection by closing internal borders and imposing strict lockdowns. This worked against a sense of collective solidarity and undermined the effectiveness of EU PD. The EU seems to lack ‘self-esteem’ in the face of dissonance, and this weakens its resilience when crises occur, making it seem that the EU is unwilling to stand up for itself. The EEAS could play a much stronger role in this respect by engaging in a long-term PD strategy; only then can the EU’s crisis PD be effective. The recovery plan signed in July 2020 signaled the beginning of the end of the crisis, giving the EU the opportunity to regain some of the ground it had lost, but it will take more than a one-off recovery plan to rekindle a sense of cohesiveness. This would require protective strategies like reinterpreting one’s identity, maintaining self-integrity, and reinforcing self-adequacy. Even though the EEAS can help build a strong voice for Europe, it would still be illusory to hope for a “single voice”. When member states neglect to reinforce the EU and their membership of it, the EU becomes a more vulnerable target for negative perceptions for audiences both within and beyond the bloc. It also makes the EU and its citizens easier to ignore. The EU is clearly stronger when its constituent parts seek to convey a united front and are able to communicate to outsiders just how much they have actually invested in their common European project.

This realization is reflected in the EEAS’s digital activity during the covid-19 crisis. A textual content analysis of our findings revealed that the EEAS used counteracting incorrect media coverage branding, as well as framing and narrative methods. However, it did not create a unique covid-19 hashtag. Rather than creating a separate PD campaign, the EEAS integrated its covid-19 messaging into the existing “unity and solidarity” discourse. In so doing, the EU showed that it remains true to its guiding principles, even in times of severe crisis. It also reflects one of the complicating factors when one considers the EU’s PD historically: namely, that it has been directly primarily inwards. In fact, the complex interlinkage between the internal and external dimensions of EU PD is part of its ongoing identity construction.

In terms of engagement, the EEAS used links in the majority of its tweets, thereby validating the digital society’s norms of openness and transparency. Even though the Service chose English as the main language it uses worldwide, it still invests in translating the core message into local languages in accordance with the latest NPD trends towards a more personalized diplomacy. A great deal was also invested in creating original visual content, as three out of four tweets included some kind of multimedia. The results were rather satisfying, as 80 percent of the tweets received some kind of feedback (in the form of likes, mentions and retweets), while 60 percent received comments from online users. What is still missing, however, is two-way symmetrical communication between the public and the EEAS, as the latter did not respond to any user comments during the six-month period analyzed for the purposes of the paper, and only provided one opportunity for live dialogue, with a single Q&A.

It is clear, therefore, that digital capabilities are crucial in the emerging hybrid world of diplomacy. The past decade has seen the accelerated digitalization of EU PD, which as noted in the introduction, is understood as a long-term process by which practitioners adopt different technologies to obtain policy goals. With that in mind, the coronavirus crisis is an interesting case-study in this respect, since it functions as a crash-test for the digital readiness of the EU’s PD. It showed that EU institutions need to exploit the benefits of DD to the full, if they wish to improve their image and reinforce their legitimacy and efficiency in the world. In fact, in July 2022, and in the midst of the Russia-Ukraine War in which digital technologies have played a crucial role, the Council of the EU published a policy report outlining the EU’s new approach to the digitalization of diplomacy (https://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-11406–2022-INIT/en/pdf).

It also needs to ensure that digitalization works on the basis of inclusivity, increased transparencyand the communicating of shared challenges to the countries and citizens of the world.

As suggested in the policy report, moving forward will require the development of a coherent approach rooted in building on the digital capacities of member states and engaging in knowledge sharing (especially with regard to the strengths and weakness of the member states) to ensure the resilience of the EU’s digitalized diplomacy, to protect it from digital risks (such as hybrid warfare and disinformation), and to protect the right of EU citizens to have access to accurate information in a safe and inclusive online environment. Similarly, it is also suggested that the EU should regulate digital spaces through collaborations with member states, joint diplomatic efforts in multilateral forums such as the OSCE, NATO and G7, or enter into dialogue with tech companies, governments and civil society organizations.

Facilitating actual dialogue—as part of the EU’s digital PD–is a challenge that could help build a heightened sense of European citizenship, solidarity and trust among Europeans.

These proposals are a move in the right direction, as they underline the need for and necessity of the EU being proactive and preparing to deal with the developments that ongoing digitalization will bring in the form of, for instance, virtual reality, holograms, deep fake news, and virtual environments. However, the EU should not only work to comprehend how future innovations will challenge PD by investing in the regulation of digital tools and environments alone. It also needs to ensure that digitalization works on the basis of inclusivity, increased transparency, and the communicating of shared challenges to the countries and citizens of the world[43]. Successful PD begins with listening, and advances through dialogue. In this context, facilitating actual dialogue—as part of the EU’s digital PD–is a challenge that could help build a heightened sense of European citizenship, solidarity and trust among Europeans; this, in turn, would help the EU succeed in conveying a better image to the rest of the world. More specifically, as Anholt (2007) explains, one of Europe’s many reputational issues is a technical one: the word ‘Europe’ can mean quite different things to different people in different contexts. For Europeans, the EU is not the same thing at all as the continent of Europe; for them, its strongest associations are with Europe-as-institution. Fore Europeans, therefore, the ‘EU’ stands unequivocally for the political and administrative machinery of Europe, and is associated by some with factors that are at best tedious and at worst dysfunctional. The EEAS should therefore not only listen to its public and post engaging content on SNS, it must also engage more actively in dialogue with online users in order to render the EU-as-institution less impersonal; this is the way to win the hearts and minds of citizens both within and beyond the Union.

The need of the EU to move in this direction is not new: it has always been a necessity. Today, however, in an age of successive crises and disruptions, it is even more imperative[44]. The pandemic seems have to have worked as a turning point in this regard: indicatively, the European institutions decided in 2020 to go ahead with the Conference on the Future of Europe (2021–2022), a pan-European exercise of participatory and consultative democracy which enabled citizens to make proposals for the EU’s future priorities. Regaining citizens’ trust is a major challenge. The task of the EU’s institutions and member states is not only to defend liberal democracy against strong external threats, but also to prevent it from dying from within.

The birth and development of the EU was and is based on a simple idea: connecting nations and peoples with the goal of peace. However, Brexit, the election of Donald Trump, and the behavior of other countries—from China and Russia to Turkey and Brazil–, point in a direction in which nationalism and power may prevail over interdependence, cooperation and dialogue. As Leonard (2021) argues, interdependence does not only connect the world, it also divides it. Hyper-connectivity polarizes societies and cultivates envy, while also providing new “weapons” of and for power and competition. Countries engage in conflict by manipulating what binds them together—using, for example, sanctions, boycotts, export controls or import bans. The pandemic should have united the planet. Instead, we saw mask diplomacy and vaccine competition, which came to resemble the space and nuclear confrontation between the US and the USSR during the Cold War.

The EU responded to the Russian invasion of Ukraine with coherence and determination, imposing sanctions and supplying, for the first time, weapons to a country under attack. The member states also overcame their differences on the issue of refugees, opening their borders to the Ukrainians who left their country. However, there is no denying that the European Union has entered a period that will highlight many problems that require difficult decisions and decisive action. How can the EU enhance its defense and security position without diverting its attention to the (unrealistic and dangerous) re-militarization of European politics and thus the weakening of global governance? How can it deal with the root causes of today’s problems? Should “soft power” be abandoned? Has the time come for “hard power”?

The challenge facing the EU’s institutions and member-states is finding a way to strengthen defense capacity without undermining the principles of European integration. The EU needs to develop its tools to enable it to be more resilient and efficient, by investing in better decision-making through majority, by strengthening the Commission’s role, by setting up a European Security Council and a European Monetary Fund. But the mistake the EU must not make is eradicating the identity it has cultivated for itself and its role in the world. It must, and it is necessary to, do more in the defense and military fields. However, it must not redirect its identity and forget that, in addition to military/armaments and geopolitical issues, there are issues ranging from the climate crisis, development, prosperity, terrorism and immigration, where its role is extremely important.

Frightened, indecisive and with no sense of direction, there is a danger the EU will slip into the chaos of armaments and conflict, undermining its “soft power” and regulatory role in global governance.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine threatens to push the EU into a new bipolar condition, strengthening the USA’s hegemony in the Western camp and China’s in the east. Also worrying is the use of rhetoric in both the USA and the EU that is based on Cold-War terminology: the “West” and the “Free World”. In a world that has changed radically over the last 70 years, such terminology is an ideological throw-back which threatens the stability of the changing world order. First, there is no ideological depth to the conflict between the USA and Russia today. Second, the world today is not bipolar but unipolar, including great powers such as China, India and Brazil. Third, globalization, with all its pros and cons, has created realities whose rupture could prove a source of chaos. In this context, policies of self-sufficiency and re-militarization could lead to major regional or global wars, as they did in the past. Such moves are the exact opposite of what is needed today. An overemphasis on absolute ideological divisions lead to divisions that are hard to bridge, thus increasing the possibility of political and military conflicts. However, pandemics, climate change, food and energy shortage know no borders: they require global cooperation. Frightened, indecisive and with no sense of direction, there is a danger the EU will slip into the chaos of armaments and conflict, undermining its “soft power” and regulatory role in global governance.

The EU has all the “qualifications” needed to avoid this. The “Brussels Impact” has produced impressive compliance, if not consensus, on critical cross-border issues. While many believe that we are moving into a bipolar world, in which we will be forced to choose between China and the US, the EU has its own unique strength—and is well equipped to exercise it[45]. Along with the US and China, Europe is one of the three main pillars of today’s global politics. Each of the three has its own ideas, priorities and capabilities in global politics: The US is primarily the “gatekeeper”. The ubiquitous presence of the dollar and its dominance on the Internet allow it to exclude countries from the global financial system or to put their citizens under surveillance. Its military and defense and technology give it the characteristics of a unique superpower. For its part, China aspires to connect other countries with its market and integrate them into a Chinese sphere of influence. But Europe has a different approach: it is a rule maker. The thousands of pages of the acquis communautaire, which governs everything from gay rights and the death penalty to sound emissions and food safety, are the EU’s operating system. Yes, there are problems, entanglements and indecision within the EU[46]. What is certain, however, is that the EU must reassess the situation, set new strategic priorities and, above all, show dynamism and courage in an environment that has already changed and will continue to become more competitive, aggressive and uncertain.

[The EU] must also strive to create inclusive digital spaces that are not restricted to like-minded areas and countries, but respond, too, to multipolarity and the emergence of forces outside the West.

The EU should therefore also proceed with a PD strategy guided by the logic that “power with others” is more important than “power over others”. Thus, apart from wanting to play a leading role in regulating digitalization, it must also strive to create inclusive digital spaces that are not restricted to like-minded areas and countries, but respond, too, to multipolarity and the emergence of forces outside the West. Because China and Russia are not expected to comply with US and EU recommendations, the post-pandemic and post-war era is likely to be characterized by cooperation only on issues where it is necessary and there is no other option (climate change); in other matters such as security, economy, trade, etc., polarization and non-cooperation will probably increase. To deal with this possibility, the EU will have to reflect on how it found itself in its current predicament. How has overconfidence in its own charm and model distorted and undermined the EU’s perspective on itself and the rest of the world? Why did the liberal expectation that the EU could transform its immediate neighborhood and the “rest” prove illusory? Self-confidence and a belief in, and overestimation of, the superiority of “European culture” and liberal democracy is not always a virtue. The results of the vote to expel Russia from the Human Rights Council of the United Nations are indicative: 93 in favor and 24 against, with 58 abstaining. Rising food and energy prices, plus a history of Western double standards, do not help. Particularly in the Middle East and Africa, the West’s concern for Ukraine’s national sovereignty is seen as selfish and hypocritical, in part in the light of the US-led invasion of Iraq and the 2011 NATO bombing of Libya. What can one say about the support reserved for Ukrainian refugees in Europe, compared to the lack of support provided for Syrian refugees? Times are certainly difficult, but when the developed EU only cares about “its own”, how certain is it that it will be safe if everyone else is not safe. This is “greed that looks like a deadly sin”.

Thus, the exercise of humility and an effort to make the EU a forum for understanding the “Others”, along with communicating and discussing their differences and priorities, would be useful. If the EU wants to maintain the power of its liberal values, it must focus on how to turn its soft-power orientation into a decisive element. Only in this way will the EU be able to hope that it can inspire. And the EU has all the qualifications needed to draw up this strategy. Thus, it is necessary to reassess the situation in an environment that has already changed and will continue to become more competitive, aggressive and uncertain. If this is not a good reason for rethinking the EUs PD, then what is?

[1]Kurbalija, J. (2020) “Diplomacy goes virtual as the coronavirus goes viral”. Diplofoundation. Accessed 23 March 2021. https://www.diplomacy.edu/blog/diplomacy-goes-virtual-coronavirus-goes-viral/

[2] Manor, I. (2020a) “2020: The Year of Digital Resurgence – Exploring Digital Diplomacy”. Accessed 23 March 2021. https://digdipblog.com/2020/12/24/2020-the-year-of-digital-resurgence/#more-3930

[3] Cull, N.J. (2008) “Public Diplomacy Taxonomies and Histories”. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 616 (1):31-54.

[4] Manor, I. (2017, August). The Digitalization of Diplomacy: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Terminology. Working Paper. Exploring Digital Diplomacy.

[5] Kurbalija, J. (2016) “25 Points for Digital Diplomacy”. Diplofoundation. Accessed 23 March 2021. https://www.diplomacy.edu/blog/25-points-digital-diplomacy/

[6] Twiplomacy Study 2018. Accessed 21 June 2021. https://twiplomacy.com/blog/twiplomacy-study-2018/. See also Twiplomacy Study 2015. The EEAS and Digital Diplomacy. Accessed 21 June 2021. https://twiplomacy.com/blog/the-european-external-action-service-and-digital-diplomacy/, Twiplomacy Study 2020. Accessed 21 June 2021. https://twiplomacy.com/blog/twiplomacy-study-2020/, Diplofoundation 2016. “Infographic: Social Media Factsheet of Foreign Ministries”. Accessed 29 August 2021. https://www.diplomacy.edu/blog/infographic-social-media-factsheet-foreign-ministries

[7] Manor, I. (2016) “Are We There Yet: Have MFAs Realized the Potential of Digital Diplomacy?” Diplomacy and Foreign Policy. 1(2):1-110.

[8] Bjola, C. and Zaiotti, R. (2021) Digital Diplomacy and International Organizations. Autonomy, Legitimacy and Contestation. Routledge: London & New York.

[9] Baumler, B. (2019) EU Public Diplomacy Addapting to an Ever-Changing World. Los Angeles: USC Center on Public Diplomacy.

[10] Abratis, J. (2021) Communicating Europe abroad: EU delegations and public diplomacy. Los Angeles: USC Center on Public Dplomacy.

[11]Manor, I. (2014) “Exploring the EU’s Twiplomacy”. Accessed 23 March 2021. https://digdipblog.com/2014/10/05/exploring-the-e-u-s-twiplomacy/

[12] Tweets (links and comments) were examined and last accessed on July 30, 2021.

[13]COVID-19: Embracing digital government during the pandemic and beyond. United Nations: Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Accessed 9 June 2021. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/wp-content/uploads/sites/45/publication/PB_61.pdfun.org

[14] Chandler, R. (2011) “Communicating During the Six Stages of a Crisis”. Accessed January 17 2021. http://go.everbridge.com/rs/everbridge/images/WhitePaper_Stage2.pdf

[15] Lopreite, M. et. al. (2021) ”Early warnings of COVID-19 outbreaks across Europe from social media”. Sci Rep 11. Accessed 13 December 2021. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-81333-1

[16] Αlvarez, J. (2020) “Public Diplomacy, Soft Power and the Narratives of Covid-19 in the initial phase of the pandemic”. In Gian Luca Gardini (ed.) The World Before and After Covid-19, Intellectual Reflections on Politics, Diplomacy and International Relations. European Institute of International

[17] Joannin, P. (2020) “In the time of COVID-19, China’s mask has fallen with regard to Europe”. Foundation Robert Schuman. Accessed 23 March 2021. https://www.robert-schuman.eu/en/european-issues/0569-in-the-time-of-covid-19-china-s-mask-has-fallen-with-regard-to-europe

[18] Borrell, J. F. (2021) European Foreign Policy in Times of Covid. Brussels: European External Action Service.

[19]See https://euvsdisinfo.eu/eeas-special-report-update-short-assessment-of-narratives-and-disinformation-around-the-covid-19-pandemic/

[20] Coronavirus: EU strengthens action to tackle disinformation, Accessed 15 September 2021, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_1006

[21] Cross, M. (2017) The Politics of Crises in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[22] Manor, I. and Crilley, R. (2018) “Visually framing the Gaza War of 2014: The Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs on Twitter”. Media War & Conflict. 11(4):369-391.

[23] EEAS on Twitter (2020): European External Action Service – EEAS on Twitter: “”Solidarity is what we need to build a better Europe and a safer world” Alberto Navarro, EU Ambassador to Cuba The EU Delegation, the Member States and the Cuban authorities joined forces to take around 1,900 tourists back home #WeTakeYouHome https://t.co/gQ90C1AeSb” / Twitter

[24] EEAS on Twitter (2020): European External Action Service – EEAS on Twitter: “70 years after Today more than ever There is only one way to overcome major challenges In Europe and around the world That way is SOLIDARITY #EuropeDay #TogetherweareEUrope https://t.co/d7TKY0ww78” / Twitter

[25] Manor, I. (2020) “Europe United: An Analysis of the EU’s Public Diplomacy on Twitter”. In A. Calcara, R. Csernatoni and C. Lavallee (eds.) Emerging Security Technologies and EU Governance. London: Routledge, pp. 148-164; Manor, I. & Bjola, c. (2020) “Public diplomacy in the age of ‘post-reality’”. In P. Surowiec and I. Manor (eds.) Public diplomacy and the politics of uncertainty. London: Palgrave ΜMacmillan, pp. 111-143.

[26] Huijgh, E. (2013) “Public Diplomacy’s Domestic Dimension in the EU”. In M. Cross and J. Melissen(eds.) European Public Diplomacy, Soft Power at Work. London: Palgrave MacMillan, pp. 57-84.

[27] Vladisavljev, S. (2021) “Why Serbia embraced China’s Covid-19 vaccine”. The Diplomat. Accessed 15 January 2022. https://thediplomat.com/2021/02/why-serbia-embraced-chinas-covid-19-vaccine/

[28] Verma, R. (2020) “China’s ‘mask diplomacy’ to change the COVID-19 narrative in Europe”. Asia Europe Journal. 18(2): 205–209.

[29] Ruje, M. and Oertel, J. (2020) “Serbia’s coronavirus diplomacy unmasked”. European Council on Foreign Affairs. Accessed 21 June 2021. https://ecfr.eu/article/commentary_serbias_coronavirus_diplomacy_unmasked/

[30] Wang, J. (2020) “Public Diplomacy in the Age of Pandemics”. USC Center on Public Diplomacy. Accessed 10 January 2021. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/blog/public-diplomacy-age-pandemics

[31] Cull, N. and Anholt, S. (2020) “The Reputational Reckoning For 2020: Bad News for China”. Accessed 28 March 2021. https://uscpublicdiplomacy.org/blog/reputational-reckoning-2020-bad-news-china. See also Anholt, S. (2007) “‘Brand Europe’— Where next?” Place Brand Public Diplomacy 3(1):115–119.

[32] European Solidarity Tracker (2020), ECFR: https://ecfr.eu/special/solidaritytracker/

[33] Standard Eurobarometer 95 – Spring 2021. https://europa.eu/eurobarometer/surveys/detail/25323

[34] EUI-YouGov ‘Solidarity in Europe’ project (2020) The European Governance and Politics Programme, Accessed 23 July 2021, http://europeangovernanceandpolitics.eui.eu/eui-yougov-solidarity-in-europe-project/

[35] Albania and Italy – example of European solidarity against coronavirus (2020), Accessed 30 July 2021, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/76796/albania-and-italy-%E2%80%93-example-european-solidarity-against-coronavirus_en

[36] EEAS on Twitter (2020): European External Action Service – EEAS on Twitter: “#TeamEurope supports Nicaragua. The EU will allocate €35 million to assist the most vulnerable in the face of #COVID19: children, abused teenagers, women victims of violence, indigenous and afro-descendant ethnic groups, people with disabilities…@UEenNicaragua #EUSolidarity https://t.co/PVg9q0462W” / Twitter and EU launches new project to support children and young people in the face of the COVID-19 health emergency – European External Action Service

[37] See https://twiplomacy.com/blog/twiplomacy-study-2020/, Accessed 14 June 2021.

[38] Twenty-eight tweets in total referred to some kind of online/virtual event, webinar or live conference, such as the FAC Press Conference, the MED2020 Dialogue webinar or the video specially designed for Europe Day Open Doors.

[39] EEAS on Twitter (2020): European External Action Service – EEAS on Twitter: “70 years after Today more than ever There is only one way to overcome major challenges In Europe and around the world That way is SOLIDARITY #EuropeDay #TogetherweareEUrope https://t.co/d7TKY0ww78” / Twitter

[40] EEAS on Twitter (2020) European External Action Service – EEAS on Twitter: “How do you like @eu_EEAS website? We would like to improve your user experience. Take part in our 2-minute anonymous survey, available in 5 languages, and share your suggestions ‼️ https://t.co/nalFV9PIaO https://t.co/WIUX3ArZ8d” / Twitter, European External Action Service – EEAS on Twitter: “Help us improve your web experience by taking our 2 min survey: Our goal is to keep timely, relevant and accurate information in our website on initiatives inside and outside the EU and your feedback matters! https://t.co/Qr576BO7JQ https://t.co/7bNd7eHtrU” / Twitter and European External Action Service – EEAS on Twitter: “How much do you know about the EU? Take our #EuropeDay quiz and test your knowledge Good luck ! https://t.co/CIqXd8LOnp” / Twitter

[41] EEAS (2020): France #UnitedInDistance: Digital sector – European External Action Service (europa.eu), Belarus #UnitedinDistance: digital literacy for the elderly to stay in touch – European External Action Service (europa.eu)

[42] EEAS on Twitter (2020) European External Action Service – EEAS on Twitter: “Have you ever wanted to ask questions directly to an EU Ambassador? Take your chance tomorrow during our #EuropeDay Facebook live chat @EuropeanExternalActionService, and learn what role the EU plays in the world! #EUDiplomacy https://t.co/DKe9qB9em7 https://t.co/aPbhdIYUug” / Twitter

[43] Christos Frangonikolopoulos (2021). European Union: From the global pandemic crisis to the war in Ukraine. An ambitious proposal for democracy, dialogue and public diplomacy. Epikentro Publishers. See also Christos Frangonikolopoulos & F. Proedrou (2012) “Reinforcing global legitimacy and efficiency: the case for strategic discursive public diplomacy”, Global Discourse: An interdisciplinary journal of current affairs and contemporary thought, 2014, 4:1:49-67.

[44] Although, over the years, the institutions have approved and adopted a significant number of citizen participation processes (such as the European Ombudsman, the European Citizens Initiative, the Commission’s Public Consultations, the Citizens’ Dialogues, and Public Petitions to the European Parliament), the view remains that the EU is distant and closed to its citizens. As a result, and as evidenced by a recent research survey by the Bertelsmann Stiftung [https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/publications/publication/did/policy-brief-012022-the-missing-piece-a-participation-infrastructure-for-eu-democracy], it is unclear to citizens which procedures can be used and for what purpose. In fact, more than 54% of the respondents stressed that their voice did not count and 32% that their participation would not make a difference. The position of the experts on European issues is also indicative, with 95% of the respondents stating that knowledge on the use of the citizen participation procedures is insufficient, and 83% emphasizing that neither the institutions nor the member states really want to facilitate and encourage citizen participation.

[45] Bradford Anu (2020), Brussels Effect, Oxford University Press.

[46] Leonard, Mark (2021), The Age of Unpeace, Transworld Publishers.