Post-pandemic inflationary pressures have eroded the purchasing power of wages, reducing workers’ living standards (see previous In focus). According to Eurostat data, 8.5% of workers in the EU lived in households with a family income below the poverty line in 2022. In-work poverty rate was significantly higher among those working on temporary contracts than among those in permanent employment (12.2% and 5.2% in the EU respectively).

The problem of low wages is complex. On the one hand, it is a result of low productivity of businesses and the creation of low-skilled jobs. On the other hand, it is linked to the loss of the bargaining power of workers holding these jobs, due to the weakening of collective bargaining and the deregulation of the labor market.

Most economists agree that setting adequate minimum wages can help improve the position of low-wage earners without leading to job losses. The minimum wage can be set unilaterally by the government, possibly after the recommendation of a committee of experts (as has been done in our country in recent years), or it can be the result from collective negotiations between employers’ organizations and labor unions.

Setting the minimum wage lies in the hands of the Member States. However, in October 2022 the European Commission issued the Directive on adequate minimum wages with the aim to achieve decent working and living conditions for employees in Europe. At the same time, Member States should strengthen collective bargaining coverage to reach at least 80%.

Indeed, if national collective bargaining agreements cover all employees, the government’s adoption of the minimum wage is unnecessary. However, several countries are far from this: in Greece, the collective bargaining coverage rate has been decreased to very low levels in recent years (14.2% in 2017 according to OECD data, or 25.8% in 2018 according to ILO data).

Most EU countries have a national minimum wage. The exceptions are the Nordic countries (Denmark, Finland and Sweden) and Austria, where collective bargaining coverage is high, and where minimum wages result from collective bargaining at the national level – as well as Italy, where recent attempts to institutionalize a minimum wage did not bring results. In Germany, a national minimum wage was introduced only in 2015. The level of the minimum wage varies significantly between member states, reflecting differences in the cost of living, national economies, as well as labor market institutions.

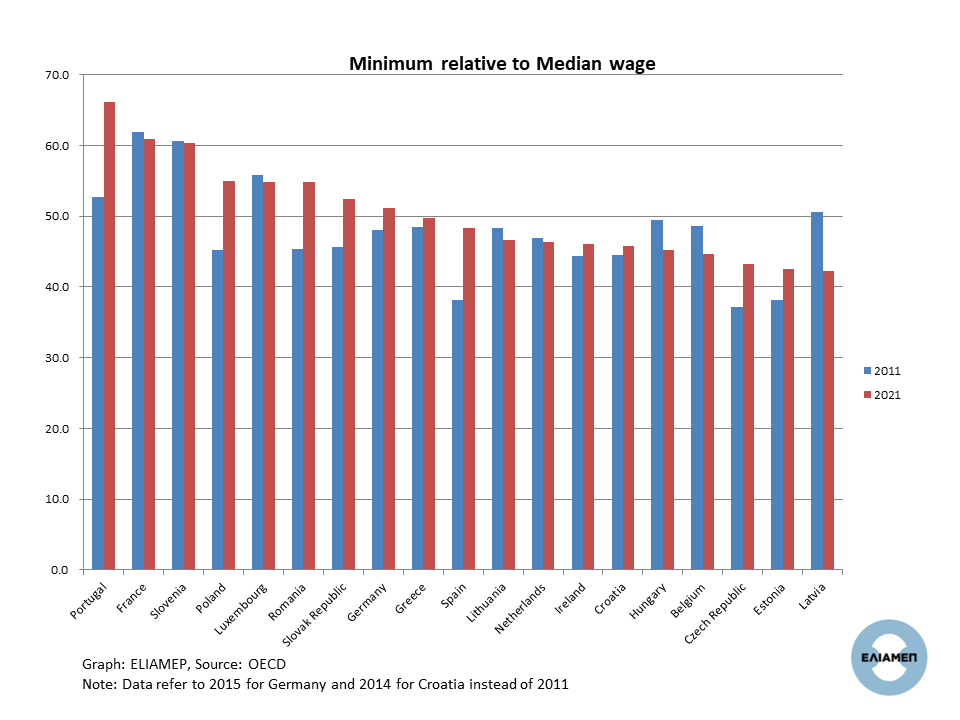

According to the European Commission Directive the threshold for setting the adequate minimum wages is 60% of the median wage or (50% of the average wage). According to the graph, in 2021 in Europe the minimum wage ranged from 42.3% of the median wage in Latvia to 66.2% in Portugal. Apart from Portugal, only in two other Member States minimum wages exceed 60% of median wages: France (60.9%) and Slovenia (60.4%).

In 2021, the ratio of minimum to median wages had increased in 11 of the 19 Member States compared to 2011 (for which data are available). The most significant increase took place in Portugal (plus 13.5 percentage points), Spain and Poland (plus about 10 percentage points). In Greece, the minimum wage as a percentage of the median wage increased slightly in 2021 (49.8%) compared to 2011 (48.5%), while this ratio had decreased significantly in 2012 (41.0%). In another 11 Member States the minimum wage still is less than 50% of the median wage.

In the last two years, however, the minimum nominal wage increased in Greece (as in other member states). Specifically, from 663 euros in January 2022, it increased to 713 euros in May 2022 and to 780 euros in April 2023 (a total increase of 17.6 percent). In April 2023 the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices increased by 10.9% compared to January 2022. Thus, minimum wage increased more than inflation.

However, it should be noted that since inflation is mainly driven by rising energy and food prices, low-income households are mostly affected as they spend most of their income on basic goods. Also, minimum wage adjustments are periodic, while price increases are continuous. This means that until the next rise in the minimum wage, purchasing power for low-wage earners will erode further.

Fighting the poverty of low-wage workers is not an easy task. In order not to jeopardize the projected reduction in inflation, both wage increases must be “reasonable”, but also the excessive profits margins of the business sector -especially the energy sector- must be contained (see previous In focus). One way to compensate low-income households for rising prices in conditions of generalized wage restraint—in addition to raising the minimum wage—is to have other compensatory policies. Targeted income support for vulnerable households, for example, can help coping with the cost of living crisis (see relevant ELIAMEP study).