- The analysis traces France’s shift from a unilateral approach, exemplified by the Françafrique policy, to a more multilateral and regionally integrated strategy in Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in the Sahel region.

- The Rwandan genocide in 1994 marked a pivotal moment for French policy, prompting a transition towards greater emphasis on multilateralism and regional security initiatives, influenced by lessons learned from past interventions.

- France’s engagement in the Sahel has been guided by the principle of “African solutions to African problems,” as evidenced by efforts to support regional initiatives and collaborate with African-led peacekeeping missions.

- Despite efforts to engage the European Union in Sahelian security issues, France has encountered challenges in achieving meaningful European involvement due to divergent priorities among EU member states and skepticism towards intervention in African affairs.

- The text highlights the complexities of operational effectiveness in French military interventions, with factors such as institutional coordination, resource allocation, and strategic objectives influencing outcomes.

- France’s efforts to coordinate with EU initiatives and other international actors in the Sahel have been hindered by overlapping responsibilities, divergent mandates, and competition among stakeholders, leading to implementation challenges.

- Public opinion in Mali regarding French military presence has evolved from initial support to skepticism and criticism, fueled by perceptions of France’s colonial legacy, operational shortcomings, and conspiracy theories.

- President Macron’s approach to Africa seeks to redefine France’s relationship with its former colonies, emphasizing partnership and mutual respect while addressing historical grievances and promoting economic cooperation.

- Rising violence, political instability, and governance challenges in the Sahel region pose significant obstacles to France’s intervention efforts and highlight the need for comprehensive, sustainable solutions.

- France faces a dilemma between promoting democratic values and protecting its strategic interests in Africa, amidst shifting regional dynamics and growing scrutiny of its interventionist policies. Collaborative approaches with European partners and nuanced policy conversations are deemed essential for navigating this complex landscape.

Read here in pdf the Policy paper by Pavlos Petidis, Junior Research Fellow, ELIAMEP.

Introduction

France’s security strategy towards sub-Saharan Africa has evolved in the light of historical legacies, shifting international conventions, and practical factors. France’s military engagements in the region were previously marked by unilateral efforts to retain influence and uphold stability. However, in the post–Cold War era, there has been a progressive shift towards multilateralism. This transformation has occurred due to changing African conflict dynamics, increasing global disapproval of neocolonial actions, and France acknowledging the constraints of acting unilaterally. French operations have begun to employ peacebuilding and empowerment techniques more frequently, in the manner of international organizations like the UN, EU, AU, and ECOWAS. France upholds multilateralism but is prepared to take unilateral action to enact quick and decisive military involvement when necessary. France’s strategy highlights its flexibility and readiness to adjust methods in accordance with changing circumstances and local and international backing requirements. French security policy in Africa may seem unique relative to its foreign and defense strategies. However, it represents the pursuit of a delicate equilibrium between seeking cooperation with several parties and retaining the possibility of independent decision-making to tackle security issues efficiently. This policy paper elaborates on the multilateralization of France’s security policy in the Sahel region with a particular emphasis on Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso and analyzes France’s efforts to engage the European Union more in the region. By primarily highlighting the consequences of France’s engagement in the Sahel along with EU involvement, the paper underlines the dangers of the destabilization of the Sahel spilling over into the Gulf of Guinea.

The evolving multilateralization of France’s security apparatus in Sub-Saharan Africa

France’s robust backing for multilateral conflict resolution is the result of ongoing attempts to maintain traditional Franco-African relations while incorporating new components and implementing modern cooperation structures.

France’s robust backing for multilateral conflict resolution is the result of ongoing attempts to maintain traditional Franco-African relations while incorporating new components and implementing modern cooperation structures. Starting in the 1960s, France adopted a policy known as ‘Françafrique’, which involved cultivating strong political, economic, and military connections between French and francophone African elites as well as formulating enduring defense agreements with all Sahelian countries (Chafer, 2005). The ensuing accords allowed France to establish enduring military bases and gave it the authority to intervene in defense of African regimes that were well-disposed towards the French state yet faced challenges stemming from internal political instability or external aggression (Treacher, 2003). unilateral Interventions of this kind occurred regularly throughout the Cold War, underpinned by France’s perception of security (Erforth, 2020b). French interventions encompassed a range of military activities aimed at providing support to the incumbent regimes and safeguarding French interests within the region on a total of nineteen occasions from 1962 to 1995 (Chafer, 2020). This unilateral approach has at its core France’s ability to decide the terms of engagement, the scope of its operations, and the amount of force to be used without the need to consult external authorities that might provide legitimacy (Chafer et al., 2020). However, the genocide in Rwanda in 1994 was followed by a notable shift in French policy, with a greater emphasis thenceforth on multilateralism, the promotion of regional security through an ‘Africanization’ approach, and the pursuit of Western interests through multinational efforts (Recchia & Tardy, 2020). This was demonstrated by moves sponsored by France, Britain, and the United States to establish regional peacekeeping troops (Kroslak, 2007).

The Rwandan genocide led to a significant change in France’s Africa strategy, since the traditional unilateral strategies had proved ineffective at bringing about tangible progress and compelled France to reconsider its role as a moral actor and leader within the international community. Termed the “Rwandan moment’, this prompted a paradigm shift towards a new multilateralist approach within France’s foreign policy arsenal (Chafer, 2002). First, France recognized the need to follow mandates and standards of engagement supported by international organizations, usually the UN Security Council (UNSC), preferably with support from regional organizations like the EU and the AU. In this context, France was obliged to help African military forces deal with their issues, in line with the idea encapsulated in the mantra ‘African solutions to African problems’ (Chafer et. al, 2020). Second, France’s mission parameters were no longer determined unilaterally and without consulting others. Notably, in response to the imperative of garnering support from other major global actors, France understood the need to adopt novel regulations governing mission parameters, duration, and the use of force as elucidated by entities such as the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and the European Union (EU), along with contributing nations (Chafer, 2020). This transformation became apparent after the first European Security and Defense Policy (ESDP) military operation in Africa, Operation Artemis, was carried out in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) in 2003 (Chafer, 2020). While France assumed a leading role in this endeavor, it collaborated closely with other EU member states in evaluating the situation and determining the operation’s duration and scope (Chafer et. al, 2020). Third, the new multilateral policy underscored a departure from conventional practices as it necessitated the integration of diverse military contingents from the African continent into joint peacekeeping missions alongside French troops (Chafer, 2020). Signifying a marked shift from past methods, this policy was implemented for the first-time during Operation Turquoise, with five hundred soldiers from various nations including Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, Chad, Mauritania, Egypt, Niger, and the Republic of the Congo participating in the operation alongside French forces (Chafer, 2020).

The French intervention in the escalated crisis in Côte d’Ivoire highlights the initial challenges multilateralism faced as a military implementation doctrine, but also underscores the temptation of operational unilateralism for French policymakers if conditions on the ground necessitates prompt and robust military action (Chafer, 2020). Initially, France acted unilaterally to prevent rebel advances in the country, dividing it in the process. Subsequent attempts at multilateralism involved ECOWAS and UN interventions, but French forces continued to operate independently (Recchia, 2020). Tensions escalated after an attack by Ivorian forces on a French military base prompted unilateral retaliation from President Chirac. In response to the crisis, France pursued a strategy of engagement with international organizations such as the ECOWAS and UN (Chafer, 2002). This approach was driven by the strain on available resources for financing missions and an effort to mitigate accusations of neo-colonialism leveled by African societies and to quell the resurgence of extreme nationalist sentiments. This resulted in a hybrid intervention model in which French and UN forces worked side by side in a multilateral context, albeit with French influence driving the decision-making. However, questions arose about the extent to which these interventions could truly be considered multilateral, given France’s significant role in the decision-making process. Despite setbacks, subsequent French presidents, including Chirac and Sarkozy, continued to pursue multilateralization, particularly through involving the EU in African peace and security actions (Recchia & Tardy, 2020). Overall, France’s evolving approach to Africa has been characterized as incremental adaptation, normalization, or bewilderment. Although different authors reached somewhat different conclusions, there was a consensus that international interventionism had become the new standard, disrupting the previously close relationships between former colonizers and colonized nations. The shift from a traditional to a fresh approach in Africa led to a significant restructuring of the French defense system in Africa (Chafer et al., 2020).

The Sahel and France’s efforts to engage the EU in the region

The «Africanization» principle

After his election, President Hollande wanted to foster a new era in France’s relations with Sub-Sahara, clearly striving to mark a rupture with the policy incongruities as well as paternalistic tones of Sarkozy’s era exemplified in his speech in Dakar in 2007 (Cumming, 2013). Hollande’s Africa Strategy was clearly aligned with the “African solutions to African problems” mantra, stating in an interview he granted with France24 that the French government will assist the Sahel countries and especially Mali to counter jihadist attacks by providing logistical and intelligence support without, however, putting its own soldiers in the field (Chafer, 2020). His ascension to the Presidency coincided with the stated priority of supporting African-led solutions to the security problems faced by the Sahel countries, which are highlighted as primarily an African priority (Recchia, 2020). In this context, France activated its diplomatic channels to initially succeed in obtaining approval from the United Nations Security Council to support the ECOWAS plan to mobilize 3000 troops to Mali so that there is a legal basis for the actions to be followed and convince the EU to send military personnel to train the African-led International Support Mission to Mali (AFISMA) and start rebuilding the country’s fractured and ill-disciplined army (Guiffard, 2023). Central to this approach was the aim to gradually withdraw from the region thereby bolstering its international reputation as a proactive mediator of peace. Initially hesitant about getting involved, France’s sense of responsibility as a global power, the constant clashes between the army and the insurgent groups and the fear of disintegration of Mali’s territorial integrity and constitutional order with effects to the regional stability as well as French national interests prompted the decision to start Operation Serval in January 2013 (Boeke & Schuurman, 2015). This action underlined the use of operational unilateralism as a means to deter the formation of terrorist sanctuaries to safeguard French interests thus halting the migratory flows passing from Agadez to Libya and from there to Europe (Bøås, 2021) but also highlighting the balance of power and the inherent complexities within the decision-making processes within the French administration (Henke, 2020).

Moreover, the spatial dimension of security issues in the Sahel, which is marked by porous borders and areas without effective governance, emphasized the need to protect European security from attacks originating in the region, as stated in the 2013 French Defense White Paper

Shortly after the launch of Operation Serval, the French intervention was criticized as a resurgence of French neocolonialism and a perpetuation of la Françafrique under Hollande’s leadership. As clearly analyzed by Chafer (2014), the geopolitical perspective acknowledges the historical and geopolitical importance Mali played in France’s post-colonial sphere of influence in Africa, thus ensuring France’s assertion of global power status. Furthermore, although Mali was not perceived as major economic hub for high level of investments, the wider region was of great strategic significance because of the energy security provided by Nigerien uranium and the presence of French companies throughout the Sahel (Chafer, 2014). Moreover, the spatial dimension of security issues in the Sahel, which is marked by porous borders and areas without effective governance, emphasized the need to protect European security from attacks originating in the region, as stated in the 2013 French Defense White Paper (Chafer, 2014). In recent years, the emergence of the necessity narrative signified the move towards the original discussion on the importance of Africanizing security in the region and underlined France’s move from acting independently to cooperating with African regional organizations such as ECOWAS and the AU (Chafer, 2014). This regionalization approach signified a move form “African solutions to African problems” to “Sahelian solutions to Sahelian problems” and was exemplified with Operation Barkhane, which was designed to combat security threats in collaboration with the G-5 Sahel countries (Lopez 2019, Bøås 2019). Operation Barkhane was structured as an expansive endeavor with a broad geographical reach and was closely integrated into the established multinational peacekeeping framework. The purpose of the operation was to enable France’s regional allies to independently assure their own security, a goal which has led to the creation of the G5 Sahel Joint Force. External analysts feared that more emphasis will be given to the security interests of all the parties involved against the development of the priorities of the newly formed organization (Bøås, 2018). In 2017, President Emmanuel Macron emphasized the auxiliary nature of Operation Barkhane, noting that it was not intended to supplant international peacekeepers. Instead, the French initiative should be seen as supplementing efforts to ensure the effective operation of MINUSMA. (Macron, 2017).

The limits of Europeanization

In parallel with Africanization, the Europeanization principle sought to prevent accusations of neo-colonialism and to share the risks and expenses of military operations among other EU member states. Neither of these notions was completely novel and it is echoed until today with President Macron having underlined in previous period the need for EU to bolster its defense and thus its establish its strategic autonomy militarily.

In parallel with Africanization, the Europeanization principle sought to prevent accusations of neo-colonialism and to share the risks and expenses of military operations among other EU member states. Neither of these notions was completely novel and it is echoed until today with President Macron having underlined in previous period the need for EU to bolster its defense and thus its establish its strategic autonomy militarily (Martin, 2023). Since the 1990s, France has strongly supported establishing a robust European defense system (Tardy, 2020). In 1997, Prime Minister Jospin implemented RECAMP, aimed at leveling up the state peacekeeping operations of its previous colonies, while President Chirac (2002–2007) strove to define the operational procedures of military deployments by setting European standards that had to be followed, as well as emphasizing the cultivation of African capabilities through strategic dialogue with the African Union (AU). EU member states, including Germany, expressed their dissatisfaction with the comprehensive effectiveness of direct EU military involvement after Germany joined French-led military operations under the ESDP in 2003–2009. It is widespread knowledge that a number of EU member states did not consider Africa as the center of their security interests and could not estimate either the political or the economic consequences of their involvement in African security issues. Some were not in favor of France taking the lead in handling emerging military issues simply because it was present and ready to intervene in the region. When framing the Malian crisis as a security threat, French decision-makers emphasized the proximity between Europe and the Sahel and portrayed the Malian crisis as an immediate threat to Europe, using phrases like ‘the constitution of a terrorist base . . . heavily armed on Europe’s doorstep’ when urging the EU to get involved (Erforth, 202a). However, they grew frustrated when persuading other Member States of the seriousness of the crisis and its potential consequences for Europe proved difficult. As a result, France’s initial goal of involving other European countries in its military adventures in Africa was short-lived, as no troops from other EU member states have been sent to Africa for combat operations since EUFOR Chad/CAR.

In particular, France altered course by acknowledging that the EU was not suited to quick, high-risk operations, but noting that its role could be beneficial when it focuses on less intense activities such as training, peacekeeping, and policing missions. It no longer aimed to Europeanize its military interventions, but increasingly prioritized a ‘division of labor’ strategy with the EU playing a supporting role.

Following its military intervention in 2013, Paris diligently endeavored to internationalize the crisis in the Sahel region and to integrate its management, explicitly focusing on European involvement (Pye, 2021). In particular, France altered course by acknowledging that the EU was not suited to quick, high-risk operations, but noting that its role could be beneficial when it focuses on less intense activities such as training, peacekeeping, and policing missions. It no longer aimed to Europeanize its military interventions, but increasingly prioritized a ‘division of labor’ strategy with the EU playing a supporting role (Henke, 2017). This aligned with France’s post–Cold War use of multilateral cooperation to back its interventions in Africa, which proved to be highly successful (Bøås, 2021). The EU was responsible for retraining the Malian army through EUTM Mali, while UN forces were focused on peacekeeping in MINUSMA. The EU also deployed two civilian CSDP missions (EUCAP Sahel Mali and EUCAP Sahel Niger) to train the police forces of these countries in counterterrorism tactics and strategies (Baudais & Souleymane, 2022). The EU has provided assistance to Sahel countries through several strategies and plans including its “2011 EU Strategy for the Sahel” and the “Sahel Regional Action Plan 2015–2020”. In this context, French policymakers chose a European non-combat assistance mission as a backup plan after failing to persuade their European colleagues to participate in a high-risk endeavor. By adopting this approach, France was trying to spread the economic, military, and political responsibilities of intervention among its partners. Europe also contributed significantly by providing financial resources for security-focused initiatives, including efforts to stabilize local governing bodies, and conducting missions to monitor and secure borders (Goxho & Diallo, 2023).

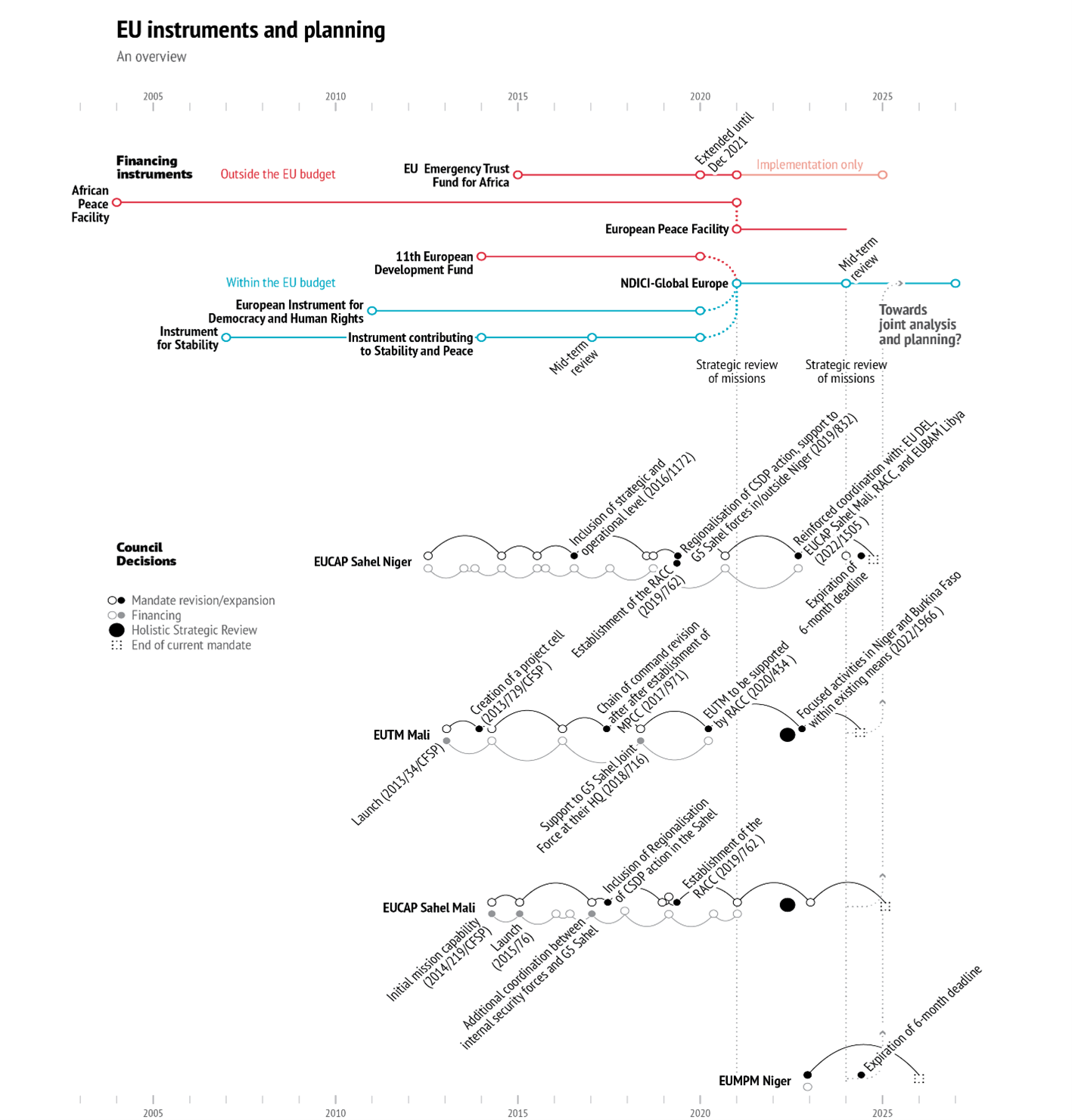

France’s current leadership ambitions in Europe may not be as strong as they were in the de Gaulle era. However, President Macron has emphasized the importance of European defense capabilities in addressing modern transnational threats and challenges in order to safeguard France’s sovereignty (Tull, 2023). The Sahel Alliance, formed in 2017 thanks to the joint efforts of France, Germany, and the European Union, has served as the principal platform to integrate development, political, and security efforts in the Sahel, emphasizing the need for coordination across sectors, mutual accountability, innovative practices, and support for security forces but encountered inconsistencies in defining its role and structure leading to various relaunches and restructuring attempts (Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, 2023). Moreover, the introduction of a vast array of strategies, initiatives, and action plans such as the Partnership for Security and Stability in the Sahel (P3S) and the Coalition for the Sahel reflected evolving strategies to address security and development challenges in the region, albeit with lingering questions about the rigidity of the traditional development approaches as well as implementation challenges due to variations in their mandates (Golovko, 2023). The P3S, spearheaded by France and Germany, aimed at enhancing the functioning of internal security processes and justice systems and prioritizing enhanced law enforcement, governance, and non-conventional security objectives over traditional goals complementing the Alliance’s efforts (Lebovich, 2020). Instead, the P3S was confronted with difficulties regarding its roles and responsibilities. However, the Partnership was never implemented in practice as, less than a year later, in January 2020, France introduced an alternative framework known as the “Coalition for the Sahel.” The division of labor within the Coalition for the Sahel was formalized, with the European Union assuming the role of enhancing the capabilities of state forces and France taking on the primary duty of combating armed groups. For EU activities and instruments deployed, the Table below, drawn from the recent policy paper written by Rosella Marrangio offers a more in-depth view.

Figure 1. EU Instruments and Planning (Source: Marrangio, 2024)

The results of increased engagement in the Sahel

In line with the regionalization approach approved by the EU in its Sahel Regional Action Plan 2015-2020, which focused on better governance, Macron demonstrated his support for the G5-Sahel organization highlighting his belief that a multifaceted strategy that would involve regional actors and self-defense militias could address the challenges in the region including terrorism, human trafficking, and climate change.

The consolidation of Operation Serval with France’s preexisting operation in Chad namely “Operation Epervier” heralded a strategic shift with the inception of the new operation known as “Operation Barkhane” (Chafer, 2014). The transition entailed an augmented mandate to provide comprehensive support to security threat in the Sahel region and contribute to preventing the resurgence of terrorist strongholds in the region. The mandate of the Operations was broadened to include five states namely Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad, with tangible results including the high-profile eliminations like Abdelmalek Droukdel and Adnan Abu Walid al-Sahraoui (Guiffard, 2023). In line with the regionalization approach approved by the EU in its Sahel Regional Action Plan 2015-2020, which focused on better governance, Macron demonstrated his support for the G5-Sahel organization highlighting his belief that a multifaceted strategy that would involve regional actors and self-defense militias could address the challenges in the region including terrorism, human trafficking, and climate change (Pichon 2021, Venturi 2019). However, the inherent problems of operational effectiveness, the vastness of the terrain as well as the preclusion of the ECOWAS from playing a significant role in promoting peace and security engendered lock-in effects and path-dependent structures, making it difficult for the EU and subsequently for France to alter institutional configurations and policies (Plank & Bergmann, 2021). In this context, Operation Barkhane strengthened its cooperation with the Malian Armed Forces (FAMa) and the MINUSMA, incorporated the region’s security, aid, and development initiatives so as to cope with the lack of necessary human resources after it reclaimed areas from armed groups (Bagayoko, 2018). The appointment of a Special Envoy for the Sahel, the increasing involvement of Agence Française de Développement (AFD) and the establishment of the Sahel Alliance further complemented the French efforts to stabilize the region (Comms & Comms, 2021). However, the lack of political will on the part of the Malian government further complicated efforts to combat insurgents (Montclos, 2021).

In this context, the role of development assistance as an instrument should be underlined. From 2012 to 2016, France’s Official Development Assistance fell short of its commitments and objectives, namely in terms of the total amount, distribution to least-developed countries, priority countries, and humanitarian aid.

In this context, the role of development assistance as an instrument should be underlined. From 2012 to 2016, France’s Official Development Assistance fell short of its commitments and objectives, namely in terms of the total amount, distribution to least-developed countries, priority countries, and humanitarian aid (OECD, 2018). Interestingly, none of the 17 priority countries were among the top 10 beneficiaries of French aid in 2016, with only one ranking in the top 20. Additionally, in 2016, only 14% of French bilateral ODA was directed towards the 17 priority countries, indicating a notable discrepancy between stated priorities and actual allocation (OECD, 2018). Moreover, French ODA for least-developed countries witnessed a declined in volume over the period spanning from 2012 to 2016, dropping from USD 1.26 billion in 2012 to USD 1.05 billion in 2016 (OECD, 2018). For the Sahel region, the provision of limited aid resources towards the five Sahel states as well as the consistent allocation of development assistance on counterinsurgency measures rather than the political objectives stated in the official documents can be partly explained by the securitization of French development policy due to instability as well as the enhancement of the perceived legitimacy of the French military intervention. Notably the five Sahel states received only a marginal share, accounting for only 10 percent of French development assistance to Africa in 2018 (OECD, 2018). As the focal point of intervention, Mali was receiving a disproportionately low allocation of just 2.5 percent, thus delineating on the one hand the provision of restricted portions of assistance in conjunction with the rest of the neighboring countries as well as underscoring on the other hand the consistent incongruity between declared political priorities and the actual allocation of financial resources (Erforth & Tull, 2022).

The frequent rotation of staff worsened these challenges, hindering the maintenance of continuity and institutional memory within the mission. In addition, competition between EU actors over project implementation impeded their effectiveness including security initiatives namely the Support Programme to Strengthen Security in the Mopti and Gao regions and to Manage Border Areas (PARSEC) or the Prevention of Conflict, Rule of Law/Security Sector Reform, Integrated Approach, Stabilization and Mediation (PRISM) unit that were not coordinated with EUCAP Sahel Mali.

Moreover, the establishment of a comprehensive framework of coordination designed to transcend EU services and instruments had evident shortcomings. Notably, prominent example of the disparities generated can be found on the overlapping nature of responsibilities given to the EUCAP Sahel Mali and the Sahel Alliance, exemplifying the challenges associated with aligning the support towards the security sector reform and the police rejuvenation with the wider development initiatives (Freitag, 2021). However, the success of EUCAP Sahel-Mali was dictated by a range of hindrances including a lack of resources, narrow mandates, thus rendering the development of long-term, locally grounded strategies unattainable (Bertrand et al., 2023). The frequent rotation of staff worsened these challenges, hindering the maintenance of continuity and institutional memory within the mission (Bertrand et al., 2023). In addition, competition between EU actors over project implementation impeded their effectiveness including security initiatives namely the Support Programme to Strengthen Security in the Mopti and Gao regions and to Manage Border Areas (PARSEC) or the Prevention of Conflict, Rule of Law/Security Sector Reform, Integrated Approach, Stabilization and Mediation (PRISM) unit that were not coordinated with EUCAP Sahel Mali (Lopez Lucia, 2019). This lack of effective coordination stemmed from divergent viewpoints and priorities among stakeholders in Brussels and on the ground further intensifying coordination and implementation challenges (Lopez Lucia, 2019). Finally, the EUTM’s efforts at retraining the Malian army, which included training in international human rights law, clearly did not translate into its actual military practice (Tull, 2019). In connection with the French policy, the two EU Sahel Strategies tended to de-emphasize the political aspects of governance (Cold-Ravnkilde & Nissen, 2020), prompting the EU to place a higher emphasis on enhancing the capabilities of state security forces (Guiachaoua, 2021) than on implementing comprehensive structural reforms intended to enhance the state’s effectiveness in serving rural populations (Tamiko & Tuomas, 2020). Initiatives like the Coalition for the Sahel and P3S demonstrate limited efforts at fostering accountability and effectiveness within Sahelian state institutions. Implementing a new French strategy was challenging due to the involvement of multiple parties and the lack of cooperation among them. France depended on the Malian state, MINUSMA, and EU initiatives to provide population-centric elements (Lebovich, 2021).

The French army’s strategic culture places great importance on external operations (). Internal power struggles between the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in France influenced the country’s policy in Mali.

However, these actors encountered significant challenges in fulfilling this aspect of the strategy, and the Malian government lacked the necessary political determination. The French strategy primarily relied on military intervention in reaction to the crisis and failed to enhance security for most of the populace. Domestic priorities significantly limited the ability to transition from counterterrorism to a more population-focused strategy (Pye, 2021). The French public narrative emphasized the ‘jihadist’ ‘terrorist’ threat these groups posed to French interests and the necessity of ‘neutralizing’ their leaders (Pérouse de Montclos 2020). France viewed maintaining a privileged area of influence in West and Central Africa as crucial to its identity as a global power. The French army’s strategic culture places great importance on external operations (). Internal power struggles between the Ministry of Defense and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in France influenced the country’s policy in Mali (. The Ministry of Defense assumed a dominant role, hindering any shift towards less militaristic strategies. A conflict arose between, on the one hand, the immediate goals of achieving rapid counterterrorist victories and withdrawing French troops and, on the other, the overarching goals of the French intervention: namely, helping to restore Malian state sovereignty and establish peace and stability in the region. France was limited in its capacity to implement the required modifications to its strategy in Mali. The original depiction of the operation as a battle against ‘terrorism’, coupled with the decision-making process in Paris vis-a-vis the Sahel, entrenched patterns that made it hard to change direction (Plank & Bergmann, 2021). Short-term goals and decisions, such as collaborating with militias in counterterrorist missions, limited France’s ability to effectively adjust to the evolving situation, leading to political challenges in deploying military force (Lopez, 2020).

The ‘new’ Sahel and the French reaction

The Sahel region has been entrenched in a protracted crisis for more than a decade. Violence and fragmentation still persist, as several governments exhibited their inability to adequately guarantee security in the face of the escalating terrorist presence.

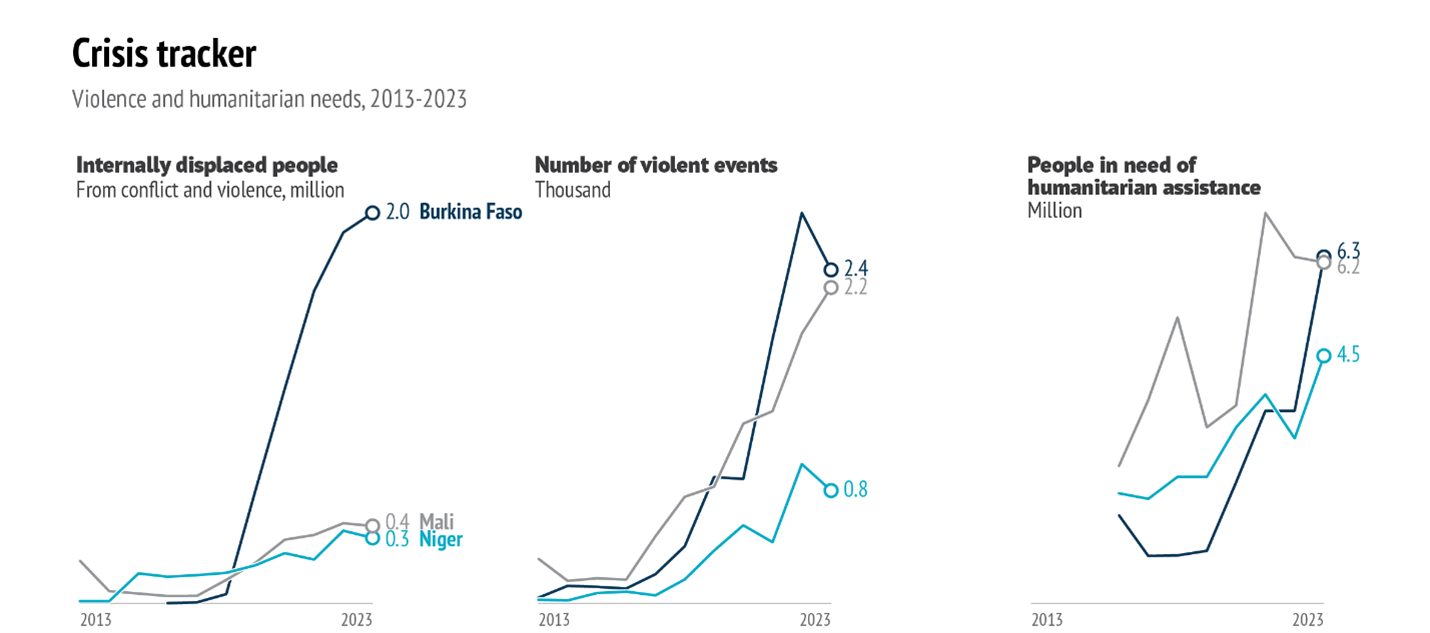

The Sahel region has been entrenched in a protracted crisis for more than a decade. Violence and fragmentation still persist, as several governments exhibited their inability to adequately guarantee security in the face of the escalating terrorist presence (Caruso & Lenzi, 2023). Between the years 2007 and 2021, there was a notable and substantial rise in the recorded fatalities associated with acts of terrorism (Baldaro, 2021) and by 2022, the level of violence escalated in terms both of intensity and of geographical scope (Figure 1, Venturi & Toure, 2023). The region has experienced a series of military coups in recent years, contradicting the prevalent notion that such events were diminishing across Africa (Sexauer, 2023). Additionally, French and European official’s efforts to establish a reciprocal responsibility framework with local governments have faced challenges (Baldaro, 2020). The coups in Mali were followed by two instances of military takeovers in Burkina Faso between January and October 2022 (Gravellini, 2023). The recent removal of President Bazoum in Niger highlights the widespread influence of regional coups, which can be attributed to a wide spectrum socio-economic factors including the insufficient economic and social progress as well as the lack of government presence in certain regions, thus creating conditions that are favorable to illicit activities like drugs, arms, and human trafficking (Tull, 2021). The situation is worsened by the presence of ethnic and religious conflicts between nomadic and transhumant pastoralist communities and sedentary farmers (D’Amato & Baldaro, 2022). Jihadists have strategically taken use of political and social grievances expressed by marginalized Fulani pastoralists and disenfranchised youth (Crisis Group, 2023). The spread of armed activism and political violence from northern Mali to Central Sahel has been accompanied by the emergence of local Katiba groups affiliated with al-Qa’ida and the growing influence of Fulani preachers who combine religious extremist ideologies with anti-state rhetoric (Wing, 2016). Finally, the actions carried out by national security forces perpetuate a pattern of ethnic discrimination against Fulani civilian communities, who are often linked to Islamist militants (Raineri & Strazzari, 2022).

Figure 2. Crisis Tracker Violence and Humanitarian needs in the Sahel region (Source: Marrangio, 2024)

The confluence of volatile political environments, neo-patrimonial tendencies and structural vulnerabilities of democratic processes have precipitated the socio-economic disparities as it can be elucidated by the Fragile State Index, the UNDP Human Development Index and the World Bank’s governance indicators (Venturi, 2019). These exigencies have provided the latitude for the military establishment to exploit the fragile state entities, citing the need to restore security and stability further compounding the institutional malaise (Crisis Group, 2021). In addition, the perceived support for military takeovers can partly be explained by ECOWAS’s inability to deter coups attempts despite its long history of being politically and militarily influential within a region rich in political upheaval namely military coups or attempts in Nigeria, Ghana, Mali, Guinea-Bissau or even civil wars in Sierra Leone and Liberia (Sotubo 2023, Mills 2022). The military incumbent regimes exploited the public discontent towards ECOWAS and its recent sanctions levelling allegations for the rising cost of basic commodities, the emergence of a severe food crisis, and condemned the French influence and intervention as genocidal (Mills, 2022). Under this context, the emergence of juntas regimes and their intent to solidify cooperation and collaboration with states other than the West has transformed the Sahel region in a focal point of multi-state competition (Murphy, 2023). The most prominent example is the enhanced engagement of Russia as part of its core strategy in Africa (Stronski, 2023). Notably, Russia intends to play an elevated role in the new “security gap” by becoming the primary source of armaments for Sub-Sahara Africa states accounting for a significant 30 percent of their total arms acquisitions for the period spanning 2016 and 2020 (Smirnova, 2022). Mali also received military equipment from Moscow in 2022, which included planes, combat helicopters, and mobile radar systems. As a result, Moscow’s renewed involvement proved advantageous when the conflict in Ukraine involving Russia erupted. In the recent UN General Assembly vote concerning the withdrawal of Russian soldiers from Ukraine, no fewer than 15 African nations opted to abstain. At the same time, Mali aligned itself with Eritrea in opposing the resolution (Ferragamo, 2023).

The emergence of safe havens outside state control in Eastern Burkina Faso, the south borders of Burkina Faso can be regarded as a significant warning for the nations situated on the Gulf of Guinea, particularly Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, and Benin. The recent incidents of 54 jihadi attacks at the northern part of Benin and constant attacks on police and military outposts in Ivory Coast are the products of a rising element of violent extremism which has acquired distinctive attributes. Indications of the proliferation of violent extremist organizations in coastal states have been visible since at least 2015.

The prevailing security patterns in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso have to be understood under the premises of the wider West Africa region (Haavik et al., 2022). The emergence of safe havens outside state control in Eastern Burkina Faso, the south borders of Burkina Faso can be regarded as a significant warning for the nations situated on the Gulf of Guinea, particularly Ivory Coast, Ghana, Togo, and Benin (Lyammouri, 2022). The recent incidents of 54 jihadi attacks at the northern part of Benin and constant attacks on police and military outposts in Ivory Coast are the products of a rising element of violent extremism which has acquired distinctive attributes. Indications of the proliferation of violent extremist organizations in coastal states have been visible since at least 2015 (Guiffard, 2023b). Togo, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Guinea, and to a lesser extent Senegal, are now faced with a comparable predicament. The coastal nations along the Gulf of Guinea are currently facing recurring instances of jihadist attacks targeting military outposts located on their northern borders (Raga et. al, 2023). In this context, the Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) has waged in an extensive and unrestrained campaign characterized by a growing number of assaults on security forces and institutions (Guiffard, 2023b). The group aspires to systematically erode vital institutions, leading to the signing of truces and accords and, ultimately, territorial concessions, decentralization, the implementation of sharia law and the closure of public institutions, particularly schools. For that reason, Benin, Cote d’Ivoire, Togo, Ghana, and Burkina Faso formalized their cooperation to combat the spread of Islamist groups under the Accra Initiative. However, recent events, including France’s withdrawal from Niger and the termination of Operation Barkhane have served to highlight the limitations of a military-centric approach to addressing the region’s complexities and failure to provide crucial social and political support leading to a widening gap between military objectives and the realities on the ground (Guiffard, 2023a).

President Macron enriched the rhetoric of a new era of cooperation with Africa with political-economic measures announcing his strategy to review the system CFA Franc transactions, and in particular the withdrawal of French representatives from the governance boards of CFA central banks.

The rise of Macron was also accompanied by a change in rhetoric on Africa, as France’s mistakes in the management of crises in the Sahel were recognized as well as the need to restructure its relations with former colonial countries. In this context, France sought to develop stronger relations and deepen the dialogue with the societies of its former colonies by diversifying the discussion cycle involving people from the business world, intellectuals, youth, artists, and diaspora members who he believed embodied Africa’s positive developments. The France-Africa Conference in Montpellier was arranged in the context of this change and was organized in a context of dialogue where, recognizing the difficulties in cultivating cooperation with the governments of certain countries, civil society and corresponding bodies participated in a platform for those who embody our relationship on a daily basis and who help forge a common future for Africa and France, including actors from diasporas, entrepreneurs, and the cultural, artistic and sporting sectors. In addition to using public diplomacy to create new cores of cooperation and deflect accusations of neo-colonialism, President Macron enriched the rhetoric of a new era of cooperation with Africa with political-economic measures announcing his strategy to review the system CFA Franc transactions, and in particular the withdrawal of French representatives from the governance boards of CFA central banks (Keita & Gladstein, 2021). Third, he is currently in the process of shifting out the 50 percent reserve requirement in favor of a new arrangement, whereby countries can gain control of their reserves, but France continues to be the guarantor and lender of last resort (Keita & Gladstein, 2021). He followed a policy of sympathy towards African countries during the pandemic by calling for a moratorium on African countries’ debt payments as “an indispensable step” to help the continent weather the coronavirus crisis, with prominent examples of Zambia’s debt restructuring program and even pushed for indebted countries to use the mechanisms offered by the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the Europeans, to cover first losses. Macron’s administration also began to modernize France’s development cooperation to enhance aid effectiveness and shift attention towards the least developed nations, especially in Africa. In 2019, the 19 priority countries outlined in French development policy benefitted from a total of 1.6 billion in Official Development Assistance from France. Among these countries, Senegal emerged as the principal recipient, receiving 281 million euros, while Ethiopia followed closely with 158 million in funding. Additionally, Mali and Burkina Faso received substantial allocations of 145 million euros and 137 million euros, respectively, reflecting the strategic significance of these nations within the framework of French ODA priorities.

The recent crisis in Niger sheds light on the inherent deficiencies in France’s African policy and especially EU’s Sahel strategies to address the needs of the migratory movements starting from Niger by imposing restrictive policies and thus generating economic hardship upon the local population, an effort stated by scholars for the EU to externalize its migration policy.

The recent crisis in Niger sheds light on the inherent deficiencies in France’s African policy and especially EU’s Sahel strategies to address the needs of the migratory movements starting from Niger by imposing restrictive policies and thus generating economic hardship upon the local population, an effort stated by scholars for the EU to externalize its migration policy (Hahonou, 2021, Hahonou 2016, Bøås & Strazzari, 2020). This includes discrepancies in its approach to authoritarian governments, the development of inadequacies in comprehensive military tactics, and persistent manifestations of paternalistic mindset (Tull, 2021). These issues have raised questions regarding the efficacy of its intervention and the broad implications for regional stability and governance dynamics (Ochieng, 2024). Vis-a-vis its involvement in Mali, though France was initially welcomed as a liberating force, it eventually lost popular support and legitimacy because it failed to enhance security in the conflict-affected areas. France’s substantial military capabilities did not align well with the changing dynamics of the conflict, causing Malians to perceive France as lacking either the determination or the ability to adequately tackle the security issues (Crisis Group, 2020). Malian expectations of the intervention were influenced by historical grievances related to France’s colonial past as the 2021 polls clearly underlined the negative sentiments deeply embedded in Malian’s collective memory (de Fougieres, 2021). The contrast between the well-equipped French military and the guerilla methods used by insurgent organizations increased distrust among the population (Bertrand et al., 2023). As a result, public opinion became more antagonistic towards the French occupation, leading to widespread discontent and demonstrations against French military convoys (Cumming et al., 2022). The growing dissatisfaction with the French military presence in Mali has been fueled by a proliferation of conspiracy theories circulating among significant segments of the Malian population, which have been amplified through social media platforms. These theories range from allegations that French troops are colluding with the jihadists and supplying them with motorcycles, to accusations of French soldiers engaging in illicit activities such as stealing gold from Malian mines or orchestrating gold smuggling operations (Bertrand et al., 2023). Prominent figures including Malian singer Salif Keita and politicians such as Oumar Mariko have contributed to the dissemination of these theories, giving them credence among the populace (Bertrand et al., 2023). This distrust of France and its motives stems from the deep-seated historical context of French colonialism in Mali, where perceptions of French favoritism towards certain groups, like the Tuareg, persist (Bertrand et al., 2023).

Concluding remarks

The Mali crisis highlights the deficiencies of France’s Africa strategy, particularly in its approach to authoritarian leaders and its paternalistic tendencies. France is experiencing a decline in its popularity and influence in Africa due to demographic shifts causing political disruptions.

The recent military coups in West Africa, such as the one in Niger, stem from a combination of factors relating to decolonization, pan-Africanism, and criticisms of liberal democracy utilized by authoritarian and populist governments. France has responded to these events with a combination of actions aimed at promoting its democratic values and human rights, as well as practical interventions to safeguard its interests. President Macron’s Africa strategy has been criticized for its ambiguities and failings, in particular the prolonged Sahel intervention that has led to defeats. France has acknowledged errors and promised a new strategy which includes prioritizing the interest of African partners and employs greater subtlety. However, its responses to incidents like the Niger coup have frequently backfired, leading to growing anti-French feelings. Macron’s inclination to overlook the historical hostility towards France’s policies in the region has further exacerbated the problem. The Mali crisis highlights the deficiencies of France’s Africa strategy, particularly in its approach to authoritarian leaders and its paternalistic tendencies. France is experiencing a decline in its popularity and influence in Africa due to demographic shifts causing political disruptions. France faces a historic challenge in having to redefine its stance towards Africa, creating an opportunity for European nations such as Germany to participate in a more collaborative and nuanced policy conversation. Given difficulties such as the Ukraine conflict and climate change, it is crucial that Europe face up to its colonial history in Africa, with a view to this impacting positively on its future interactions with the continent. Now that the military regimes that rule in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger have signed an agreement to create a new architecture of collective defense and mutual assistance, Europe—and France, in particular—is faced with a new reality that presents a dilemma: should it pursue policies centered on the promotion of values such as democracy and human rights, or adopt a pragmatic policy which, though protecting its interests, would go against its very identity?

References

Ali, R. et al. (2019). Governance and Security in the Sahel: Tackling Mobility, Demography and Climate Change. Edited by Bernardo Venturi, FEPS, Foundation for European Progressive Studies.

Bagayoko, N. (2018). Le processus de réforme du secteur de la sécurité au Mali (A Stabilizing Mali Report). Montréal : Centre FrancoPaix en Résolution des conflits et Missions de paix.

Baldaro, E. (2021). Rashomon in the Sahel: Conflict dynamics of security regionalism. Security Dialogue, 52(3), 266–283. https://doi.org/10.1177/0967010620934061

Baudais, V., & Souleymane, M. (2022). The European Union Training Mission in Mali: An Assessment.” SIPRI, www.sipri.org/publications/2022/sipri-background-papers/european-union-training-mission-mali-assessment.

Haavik, V., Bøås, M., & Iocchi, A. (2022). The end of stability – How Burkina Faso fell apart. African Security, 15(4), 317–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392206.2022.2128614

Bøås, M. (2021). EU migration management in the Sahel: unintended consequences on the ground in Niger?, Third World Quarterly, 42(1), pp.52-67, https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1784002

Bøås, M., & Strazzari, F. (2020). Governance, fragility, and insurgency in the Sahel: A hybrid political order in the making. International Spectator, 55(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2020.1835324

Bøås, M. (2019). The Sahel Crisis and the Need for International Support. Policy Dialogue no. 15. Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute. http://nai.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1367463&dswid=2870

Bøås, M. (2018). Rival Priorities in the Sahel – Finding the Balance between Security and Development. Policy Note no. 3. Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute. https://nai.uu.se/news-and-events/news/2018-04-19-rival-priorities-in-the-sahel—finding-the-balance-between-security-and-development.html

Boeke, S. & Schuurman, B. (2015) Operation ‘Serval’: A Strategic Analysis of the French Intervention in Mali, 2013–2014, Journal of Strategic Studies, 38(6), pp.801-825. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2015.1045494

Caruso, F., & Lenzi, F. (2023). The Sahel Region: A Litmus Test for EU–Africa Relations in a Changing Global Order. IAI Istituto Affari Internazionali, www.iai.it/en/pubblicazioni/sahel-region-litmus-test-eu-africa-relations-changing-global-order.

Chafer, T., Cumming, G. D., & Van Der Velde, R. (2020b). France’s interventions in Mali and the Sahel: A historical institutionalist perspective. Journal of Strategic Studies, 43(4), 482–507. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2020.1733987.

Chafer, T. (2005b). Chirac and ‘la Françafrique’: No Longer a Family Affair. Modern & Contemporary France, 13(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963948052000341196

Chafer, T. (2002). Franco-African Relations: No Longer so Exceptional? on JSTOR. African Affairs, 101(404), 343–363. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3518538

Cold-Ravnkilde, S.M. & Nissen, C. (2020). Schizophrenic agendas in the EU’s external actions in Mali. International Affairs, 96(4) , pp. 935–953.

Crisis Group (2023). A Course Correction for the Sahel Stabilisation Strategy, www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel-burkina-faso-mali-niger/course-correction-sahel-stabilisation-strategy.

Crisis Group (2021). Mali, a Coup within a Coup, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/mali/mali-un-coup-dans-le-coup

Crisis Group (2020). The Central Sahel: Scene of New Climate Wars? www.crisisgroup.org/africa/sahel/b154-le-sahel-central-theatre-des-nouvelles-guerres-climatiques.

Cumming, G. D., Van Der Velde, R., & Chafer, T. (2022b). Understanding the public response: a strategic narrative perspective on France’s Sahelian operations. European Security, 31(4), 617–638. https://doi.org/10.1080/09662839.2022.2038568

Cumming, G. D. (2013). Nicolas Sarkozy’s Africa policy: Change, continuity, or confusion? French Politics, 11(1), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1057/fp.2012.24

D’Amato, S., & Baldaro, E. (2022). Counter-Terrorism in the Sahel: Increased Instability and Political Tensions.” ICCT, www.icct.nl/publication/counter-terrorism-sahel-increased-instability-and-political-tensions.

de Fougieres, M. (2021). French Military in the Sahel: An Unwinnable (Dis)Engagement? . Institut Montaigne, www.institutmontaigne.org/en/expressions/french-military-sahel-unwinnable-disengagement.

Ekforth, B., & Tull, D. (2022). The failure of French Sahel policy: an opportunity for European cooperation? Stiftung Wissenschaft Und Politik. https://www.swp-berlin.org/publikation/mta-spotlight-13-the-failure-of-french-sahel-policy

Erforth, B. (2020a), Contemporary French Security Policy in Africa: On Ideas and Wars, London: Palgrave.

Erforth, B. (2020b). Multilateralism as a tool: Exploring French military cooperation in the Sahel, Journal of Strategic Studies, 43(4), pp.560-582, https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2020.1733986

Ferragamo, M. (2023). The Niger Coup Could Threaten the Entire Sahel, CFR, https://www.cfr.org/in-brief/niger-coup-could-threaten-entire-sahel

Freitag, V. (2021). Analyzing EU’s Sahel strategies: A civilian approach in the era of pragmatism. EUROPEUM.org. https://europeum.org/en/articles/detail/4295/policy-paper-analyza-strategii-eu-pro-sahel-civilni-pristup-v-ere-pragmatismu.

Golovko, E. (2023). Sahel: Stabilisation Efforts Should Address Internal Displacement. Clingendael, www.clingendael.org/publication/sahel-stabilisation-efforts-should-address-internal-displacement.

Goxho, D., & Diallo, A. (2023). Donor Dilemmas in the Sahel: How the EU Can Better Support Civil Society in Mali and Niger. Saferworld, www.saferworld.org.uk/resources/publications/1421-donor-dilemmas-in-the-sahel

Guichaoua, Y. (2021). The Bitter Harvest of French interventionism in the Sahel, Oxford Academic Press.

Guiffard, J. (2023a). Operation Barkhane: Success? Failure? Mixed Bag? Institut Montaigne, www.institutmontaigne.org/en/expressions/operation-barkhane-success-failure-mixed-bag

Guiffard, J. (2023b). Gulf of Guinea: Can the Sahel trap be avoided?, Institut Montaigne, https://www.institutmontaigne.org/en/expressions/gulf-guinea-can-sahel-trap-be-avoided

Gravellini, J.M. (2023). Quelles Sont Les Causes Des Crises Multidimensionnelles Qui Touchent Le Mali et Le Burkina Faso & Niger;?, IRIS, www.iris-france.org/174179-quelles-sont-les-causes-des-crises-multidimensionnelles-qui-touchent-le-mali-et-le-burkina-faso/.

Hahonou, E. & Olsen, R. (2021) Niger – Europe’s border guard? Limits to the externalization of the European Union’s migration policy, Journal of European Integration, 43(7), pp.875-889, https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2020.1853717

Henke, M.E. (2020). A tale of three French interventions: Intervention entrepreneurs and institutional intervention choices, Journal of Strategic Studies, 43(4), pp.583-606. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2020.1733988

Keita, M., & Gladstein, A. (2021). Macron’s reforms to CFA Franc don’t reduce financial dependence of former colonies. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/08/03/macron-france-cfa-franc-eco-west-central-africa-colonialism-monetary-policy-bitcoin/

Kroslak, D. (2007). The Role of France in the Rwandan Genocide. Hurst : London.

Lebovich, A. (2021). “Disorder from Chaos: Why Europeans Fail to Promote Stability in the Sahel.” ECFR ecfr.eu/publication/disorder_from_chaos_why_europeans_fail_to_promote_stability_in_the_sahel/#the-p3s-old-problems-imperfect-instruments.

Lopez L.E. (2020). Security politics and the «remaking» of West Africa by the European Union. In P. J. Kohlenberg & N. Godehardt (Eds.), The Multidimensionality of Regions in World Politics (pp. x–xx). London/New York: Routledge.

Lopez, L.E. (2019). The European Union Integrated and Regionalised Approach Towards the Sahel, Montreal: Centre FrancoPaix en résolution des conflits et missions de paix .

Lopez, L.E. (2017). Performing EU agency by experimenting the ‘Comprehensive Approach’: the European Union Sahel Strategy. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 35(4), 451–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2017.1338831

Lyammouri, R. (2022). Violence Spillover into the Coastal States. Policy Center for the New South, www.policycenter.ma/publications/violence-spillover-coastal-states.

Macron, E. (2017). Initiative Pour l’Europe – Discours d’Emmanuel Macron pour une Europe Souveraine, Unie, Démocratique, https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2018/01/09/initiative-pour-l-europe-discours-d-emmanuel-macron-pour-une-europe-souveraine-unie-democratique.

Marrangio, R. (2024). Sahel reset: time to reshape the EU’s engagement. European Union Institute for Security Studies. https://www.iss.europa.eu/content/sahel-reset-time-reshape-eus-engagement

Martin, E. (2023). Macron and the European strategic autonomy trope. GIS Reports. https://www.gisreportsonline.com/r/strategic-autonomy/

Mills, L. (2022). The Effectiveness of ECOWAS in Mitigating Coups in West Africa, International Peace Institute.

Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères. (2023). “Sahel Alliance.” France Diplomacy – Ministry for Europe and Foreign Affairs, www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/french-foreign-policy/security-disarmament-and-non-proliferation/news/2018/article/sahel-alliance-launch-of-a-project-to-support-malian-youth-20-03-18

Montclos, M.A. (2021). Rethinking the response to jihadist groups across the Sahel. Chatham House, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2021/03/rethinking-response-jihadist-groups-across-sahel

OECD. (2018). Development Co-operation Profile: France. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/29927d90-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/29927d90-en

Ochieng, B. (2024). Will the Sahel Military Alliance Further Fragment ECOWAS? CSIS. https://www.csis.org/analysis/will-sahel-military-alliance-further-fragment-ecowas

Plank, F., & Bergmann, J. (2021). The European Union as a Security Actor in the Sahel: Policy Entrapment in EU Foreign Policy. European Review of International Studies, 8(3), 382–412. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27142394

Pichon, E., et al. “New EU Strategic Priorities for the Sahel: Addressing Regional Challenges through Better Governance.” EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service, 9 July 2021, www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2021)696161.

Pye, K. (2021). The Sahel: Europe’s Forever War?” Centre for European Reform, www.cer.eu/publications/archive/policy-brief/2021/sahel-europes-forever-war#FN-3.

Raga, S. et al. (2023). The Sahel Conflict: Economic and Security Spillovers on West Africa.” ODI, odi.org/en/publications/the-sahel-conflict-economic-security-spillovers-on-west-africa/.

Raineri L. & Strazzari, F. (2022). Drug Smuggling and the Stability of Fragile States. The Diverging Trajectories of Mali and Niger, Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding, 16(2), pp.222-239, https://doi.org/10.1080/17502977.2021.1896207

Recchia, S. (2020). A legitimate sphere of influence: Understanding France’s turn to multilateralism in Africa, Journal of Strategic Studies, 43(4), pp.508-533. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2020.1733985

Recchia, S. & Tardy, T. (2020). French military operations in Africa: Reluctant multilateralism, Journal of Strategic Studies, 43(4), pp.473-481. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2020.1733984

Salaun, T., & Irish, J. (2021). France Ends West African Barkhane Military Operation. Reuters, Thomson Reuters, www.reuters.com/world/africa/france-announce-troop-reduction-sahel-operations-sources-2021-06-10/

Sexauer, H. (2023). Regional cooperation amidst coups, terrorism and transborder insecurity : What future for the G5-Sahel?, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Brussels.

Smirnova, T. (2022). Russia Challenges France in the Sahel, ISPI, https://www.ispionline.it/en/publication/russia-challenges-france-sahel-37124

Sotubo, O. (2023) “ECOWAS: In Need of Help in Niger?” RAND Corporation, www.rand.org/blog/2023/08/ecowas-in-need-of-help-in-niger.html

Stronski, P. (2023). Russia’s Growing Footprint in Africa’s Sahel Region, www.carnegieendowment.org/2023/02/28/russia-s-growing-footprint-in-africa-s-sahel-region-pub-89135

Tammikko, T. & and Tuomas I. (2020). The EU’s Role and Policies in the Sahel: The Need for Reassessment, FIIA – Finnish Institute of International Affairs. FIIA, www.fiia.fi/julkaisu/the-eus-role-and-policies-in-the-sahel?read

Tardy, T. (2020). France’s military operations in Africa: Between institutional pragmatism and agnosticism. Journal of Strategic Studies, 43(4), 534–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402390.2020.1734571

Tull, D. (2023). France’s Africa Policy under President Macron. Stiftung Wissenschaft Und Politik (SWP). https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/frances-africa-policy-under-president-macron

Tull, D. (2021). Operation Barkhane and the future of intervention in the Sahel. Stiftung Wissenschaft Und Politik (SWP). https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/operation-barkhane-and-the-future-of-intervention-in-the-sahel

Tull, D. (2019). Rebuilding Mali’s army: the dissonant relationship between Mali and its international partners. International Affairs, vol. 95, no. 2, pp. 405–422.

Treacher, A. (2003). French Interventionism: Europe’s Last Global Player?, Farnham: Ashgate.

Venturi, B. & Toure, N. (2023). Out of the Security Deadlock: Challenges and Choices in the Sahel. Foundation for European Progressive Studies, feps-europe.eu/publication/737-out-of-the-security-deadlock-challenges-and-choices-in-the-sahel/

Venturi, B. (2019). An EU Integrated Approach in the Sahel: The Role for Governance. Foundation for European Progressive Studies, Brussels.

Wing, S. (2016). French Intervention in Mali: Strategic Alliances, Long-term Regional Presence?. Small Wars & Insurgencies, 27(1), pp.59-80, https://doi.org/10.1080/09592318.2016.1123433