- The share of nuclear power in Asia’s electricity generating capacity has grown significantly over the last two decades. China is one of the dominant players in Asia, developing a robust nuclear power program. In the Middle East, Iran and the United Arab Emirates have introduced nuclear power into the region, with Turkey planning to follow in their footsteps in 2023.

- The adoption of nuclear power spurs concerns about the proliferation of nuclear weapons and nuclear latency. Some countries use their civilian nuclear programs to develop a robust infrastructure that allows them to acquire nuclear weapons in a relatively short period of time. Such dynamics are likely to have a destabilizing effect on international affairs in the Middle East and Asia.

- The current international situation makes it unlikely that the nuclear non-proliferation regime will become stronger in the near future. The war in Ukraine has demonstrated the need for a new generation of negative security assurances and collective defense that protects countries from nuclear blackmail.

Read here in pdf the Policy brief by Eliza Gheorghe, Non-Resident Scholar, ELIAMEP Turkey Programme; Assistant Professor, Bilkent University.

Introduction

Nuclear energy has increasingly featured as one of the possible solutions to the worsening climate crisis. Approximately 30 countries are contemplating, negotiating, or already setting up nuclear power programs. Of these, 80% are developing economies, which need access to affordable and clean energy to continue to expand. Turkey is expected to join the group of countries producing nuclear power in 2023. Unfortunately, the expansion of commercial nuclear power can fuel nuclear proliferation, because countries can pursue atomic weapons programs under the guise of civilian power generation. Examples of proliferants that have followed this dual track abound, especially in the Middle East and Asia. In this report, I examine the dynamics of nuclear power and proliferation in Turkey’s Asian politics, looking at the non-proliferation regime, its effectiveness, and possible ways of strengthening its appeal and enforcement mechanisms.

Nuclear Power in the Middle East and Asia

The path to producing electricity in nuclear power reactors has been tortuous, due to a lack of appropriate investments in human capital and concerns over non-proliferation.

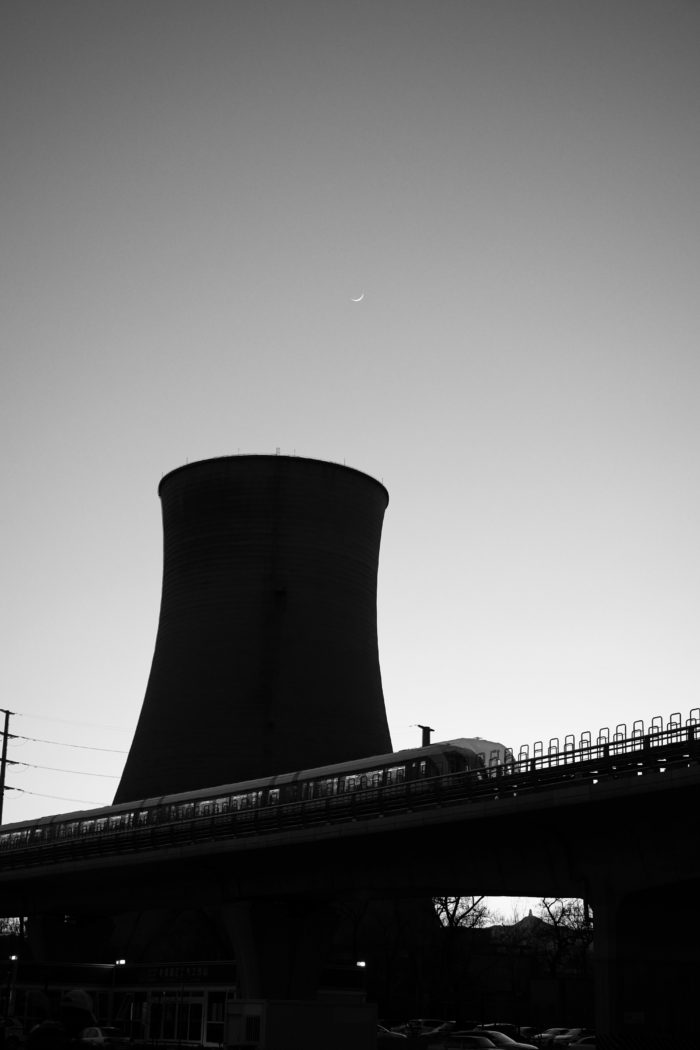

The global overuse of fossil fuels, especially by industrialized nations, combined with the worsening climate crisis have prompted discussions on nuclear energy and the development of nuclear programs to meet the energy needs of many developing countries. Nuclear energy has been adopted at a fast pace by countries in the Middle East. Three countries now lead the way in the region: Iran, the UAE, and Turkey. These developments come after decade-long efforts to introduce nuclear power into the energy mix–the path to producing electricity in nuclear power reactors has been tortuous, due to a lack of appropriate investments in human capital and concerns over non-proliferation.

The arrival of nuclear technology in the Middle East will be accompanied by substantial pressure at the regional and global levels to standardize the procedures and principles of nuclear safety and security, which will require a solid regional approach.

Turkey is scheduled to add a first nuclear power plant to its energy mix in 2023 (Grigoriadis and Gheorghe 2022). Other countries in the region are also making strides towards the acquisition of nuclear technology, including Morocco, Jordan, and Egypt. The arrival of nuclear technology in the Middle East will be accompanied by substantial pressure at the regional and global levels to standardize the procedures and principles of nuclear safety and security, which will require a solid regional approach. In Turkey, the possibility of expanding atomic energy beyond Akkuyu raises questions about attitudes towards nuclear power. A recent survey on a representative sample of the Turkish public showed a sizable minority to be in favor of canceling the construction of nuclear power plants. Over two thirds of the respondents in a recent opinion poll in Turkey saw renewables as the best substitute for nuclear power, but a majority of the public is also in favor of investments in military technology in lieu of nuclear power.

Nuclear power is expanding very rapidly in Asia, too, with almost 114 operational nuclear power reactors in the region, with another 35 under development. China has 54 power reactors in operation, India has 22, and Pakistan has six. These statistics suggest that China, having built the largest number of nuclear power plants in record time, now dominates the Asian nuclear power landscape. Nuclear power is also a significant component in the energy mix of South Asian countries (India and Pakistan), but nuclear “new build” is slower there than in China.

Regarding cooperation between Turkey and Asian countries, the strategic partnership between Islamabad and Ankara occasionally gives rise to reports that Pakistan must be providing sensitive nuclear technology to Turkey (Kibaroğlu, 1997, pp. 34–35). However, to date, these alleged links have not been corroborated. Despite the growing security cooperation between Pakistan and Turkey, nuclear development has not yet figured in the countries’ bilateral dialogue.

Nuclear Latency and Proliferation Dynamics in the Middle East and Asia

Therefore, concerns about external threats are likely to remain a strong driver of proliferation dynamics in the Middle East.

In the Middle East, the Iran-Saudi Arabia-Israel triangle has the greatest potential to destabilize the region. Tehran has already achieved nuclear latency, acquiring a sophisticated nuclear infrastructure that would allow it to nuclearize in a relatively short period of time, and Riyadh is now seeking to follow in its footsteps. None of the three is likely to swerve under the influence of traditional security guarantors—the United States and Russia — and abandon their nuclear ambitions. Therefore, concerns about external threats are likely to remain a strong driver of proliferation dynamics in the Middle East.

In South Asia, the situation is precarious due both to the regional rivalry into which India and Pakistan are locked and to the global arms race between the United States and China. Tensions flared up during the Balakot Crisis of 2019, and while Pakistan is open to third-party mediation by countries such as Turkey, India is entirely against such mediation in issues such as the Kashmir conflict.

In Turkey, a significant majority of the public supports the acquisition of nuclear weapons. Recent field surveys in Turkey shed light on the public take on the issues surrounding nuclear power and nuclear weapons. They showed that nuclear power and nuclear weapons were strongly associated in the respondents’ minds. At the same time, between 59 to 73 percent of individuals in Turkey appear to think Turkey should build nuclear weapons. This demand for nuclear weapons could be the result of security concerns about Turkey’s neighbors and its regional situation. Respondents’ answers changed in line with the potential nuclear development within its neighbors. When asked how they would receive a hypothetical intention on the part of Greece to develop nuclear power, the respondents varied in their support for such plans depending on the extent to which Athens subscribed to strict non-proliferation norms and cooperated with international institutions. For instance, if Greece signed the Additional Protocol and granted extensive prerogatives to inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Turkish respondents would be in favor of the construction and operation of nuclear power plants in Greece. These findings indicate that the general public see the development of nuclear power as a step towards nuclear weapons, even if such facilities have little latent potential in themselves. They also suggest that current efforts to get countries such as Saudi Arabia to sign an Additional Protocol with the IAEA could have beneficial effects for the region as a whole, if successful. Perceptions about the link between nuclear power and nuclear weapons can therefore be attenuated by a country’s record of compliance with the non-proliferation regime.

The Nuclear Non-proliferation Regime

India and Pakistan have neither signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) nor secured membership of the Nuclear Suppliers’ Group (NSG). Turkey advocated for Pakistan and India to be given simultaneous entry to the former and made a case for Pakistan’s membership of the latter, given Pakistan’s experience in nuclear safety and operating nuclear reactors. Despite India’s and Pakistan’s efforts and desire to join the NSG, both been denied membership; as they continue to develop their nuclear respective programs, this exclusion is likely to weaken the non-proliferation regime.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its use of force against nuclear facilities has drawn attention to the “dangers of nuclear reactors in war”.

Another factor that has likely damaged the non-proliferation regime is the ongoing war in Ukraine. Russia tried to capture the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant and use it to supply power to Russian forces in Eastern Ukraine. The targeting of the Zaporizhzhia nuclear reactors amounts to what some called “nuclear terrorism” at the time (Prokip, 2022). Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its use of force against nuclear facilities has drawn attention to the “dangers of nuclear reactors in war” (Gilinsky and Sokolski, 2022). The long-lasting effects of a nuclear accident induced by a military attack are most likely among the reasons why a sizeable minority of respondents in the above poll in Turkey were in favor of canceling the construction of nuclear power plants in Turkey. To guarantee its energy security and cater to its rising energy needs while easing the threat of climate change and its dependency on outside sources, Turkey can ensure its power plants are developed safely and securely and in accordance with the recommendations of the IAEA.

Regarding the non-proliferation regime writ large, informal mechanisms such as the bilateral dialogue between Iran and Saudi Arabia look promising. In South Asia, the inconsistent application of non-proliferation rules and norms has not helped. Countries in the Middle East and Asia should be open to nuclear energy dialogues in order to lessen their desire or ability to acquire nuclear weapons, to achieve predictability and security in their nuclear development programs, and to encourage platforms to sit and work together. In addition, traditional non-proliferation policies, such as strengthening sanctions, can protect non-nuclear-weapon states from nuclear blackmail.