According to the recent survey “What Greeks believe” by diANEOsis for the year 2022, 57.9% of Greeks state that they would emigrate abroad if they found a job with better pay and better conditions. So the trend that wants the active workforce of Greece to look for better job opportunities abroad, a trend that emerged and launched in the beginning of the ten-year economic crisis, persists today.

The phenomenon is not a Greek peculiarity. Workers from many southern European countries (Portugal, Spain, Cyprus) and Eastern Europe (Romania, Poland) migrate to central and northern European countries aiming for better job opportunities. This highlights the divergence of the core and the periphery over the past decade in the European continent, with central and northern European countries being in need and able to absorb more workers, in contrast to southern and eastern European countries which find it difficult to take advantage of their domestic workforce.

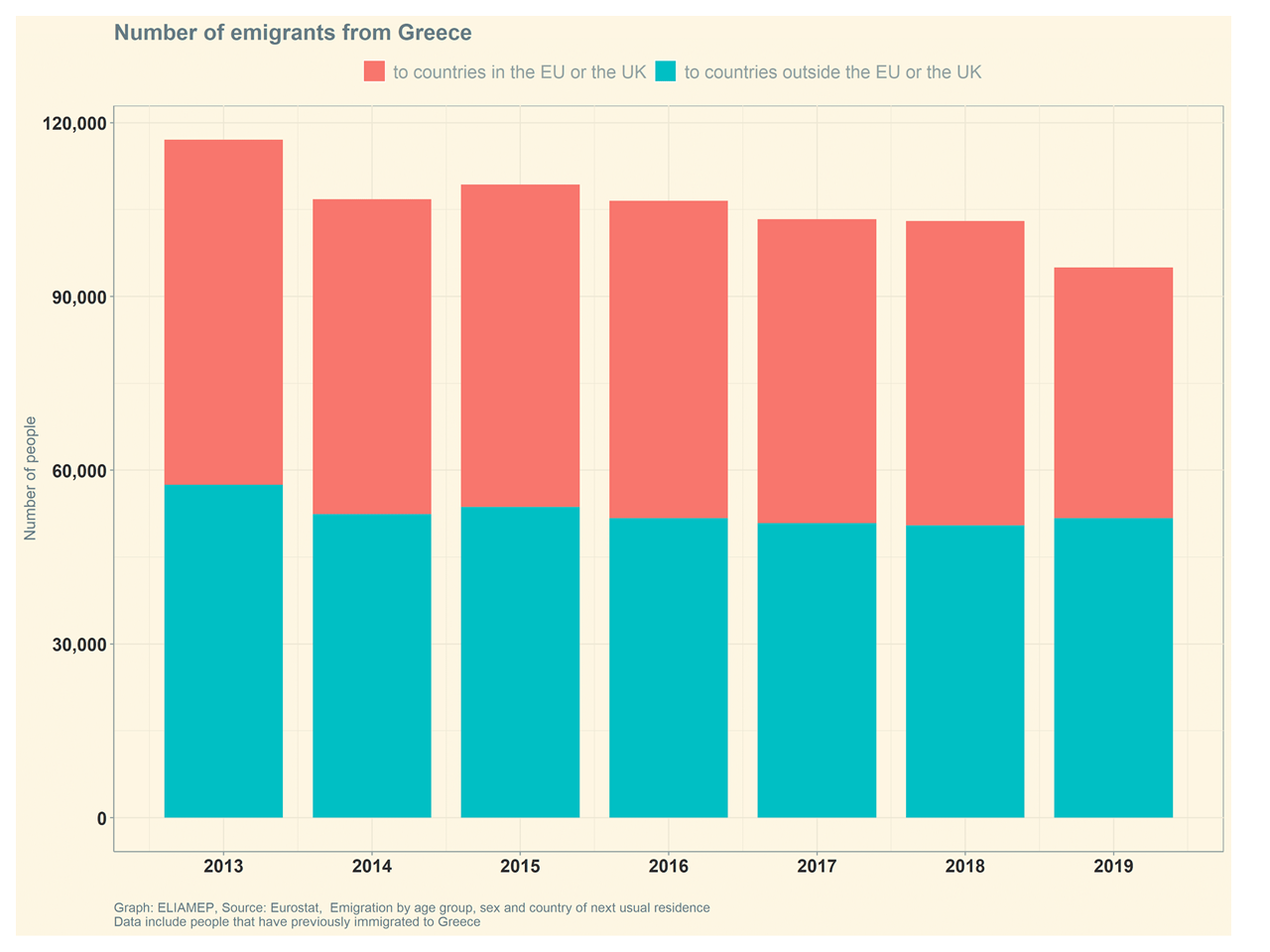

The flight of human capital is above all a huge blow to the economy. If one considers that every year about 70,000 student-candidates are examined in the national exams, Greece has been systematically losing an equal or higher number of people every year since 2013 (see graph), who should be able to find opportunities in the domestic labour market. At the same time, the loss of active labour force is causing serious malfunctions in the country’s fiscal space. The state invests in the new generation by offering free education (public schools and universities), free health care and so on. The return of this investment shifts to the future – through taxation when young people enter the labour market. These tax revenues are crucial both for the insurance system, as they finance pensions for the elderly, as well as for wider public spending. With the flight of human resources abroad, Greece has incurred the cost of an investment, while its return is directed to other countries. This results in a vicious circle in which countries deviating from the European average lose human capital and at the same time resources that could finance development and halt the phenomenon.

But labour mobility can prove to be an opportunity for the country. The employees who emigrated can transfer work experience and best practices from host countries to countries of origin. This brings added value to an economy provided that these workers return. This should be the main concern of public policy aiming to restrict the flight of human capital, the creation of these conditions which will render the Greek labour market attractive to the workforce.

None of this is new, the issue has been in the public debate since the beginning of the 2010s, but today the need to limit the phenomenon is becoming urgent. The demographic trend wants Greece to rank high among European countries, in terms of the percentage of the elderly population, therefore the loss of potential workforce and especially of young age is a luxury that Greece does not have.