Consecutive economic upheavals due to the pandemic and the war in Ukraine have put the labor market in a transitional stage seeking the new equilibrium. The picture in the European labor market is characterized by a high degree of heterogeneity both across Member States and across different sectors of the economy.

The starting point for explaining the current state of the labor market is the policies adopted during the pandemic. These are primarily responsible for the rapid and strong recovery of the labor market with the end of multiple lockdowns, but at the same time they asymmetrically affected different sectors of the economy. In Europe, the main response took the form of short-time work schemes and furlough schemes. Thanks to these measures, many jobs were retained even though working hours were reduced, the unemployment rate was kept at manageable levels, even though it increased, and the economic recovery was facilitated (see previous note).

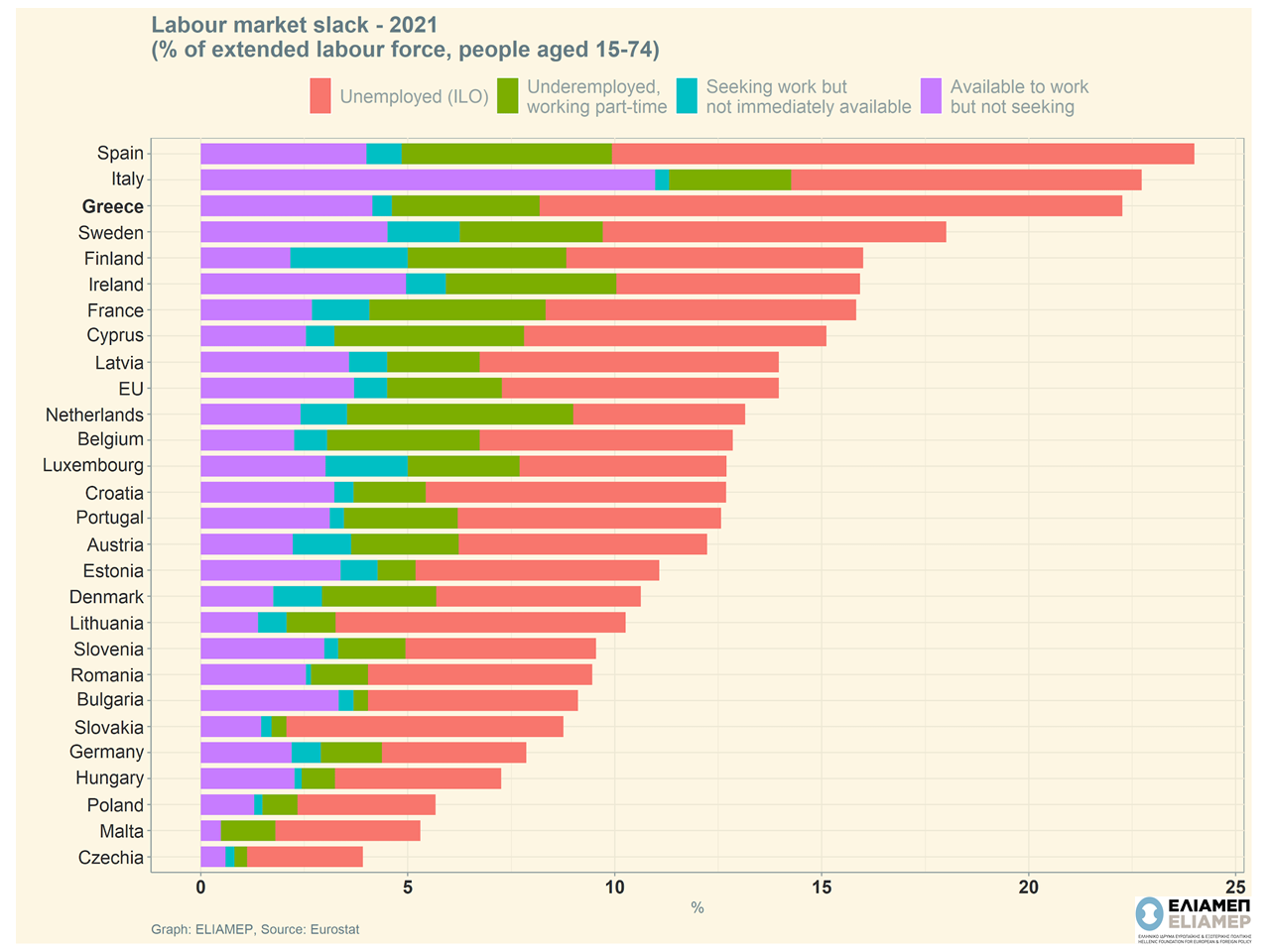

As succinctly described during the IMF’s Spring Meetings, the economic shock caused by the pandemic does not resemble previous global crises. The pandemic mainly affected contact-intensive sectors (restaurants, hospitality, etc.), while its economic impact was directly reflected in the household budget (unlike the global financial crisis of 2008 which started in the financial sector). Also, the European response to job retention mainly concerned fixed and long term contracts, exempting seasonal or part-time workers. Consequently, the picture of the labor market differs significantly by country and by sector of the economy, resulting in Member States characterized by a “tight” labour market, where demand for labor is at least equal to supply, and Member states with a “slack” labour market, where “slack” in the labour market is measured as the sum of (a) those looking for work but not finding it, (b) those looking for work but not immediately available, (c) those who are available but not looking for work, and finally (d) those who are underemployed.

The graph is indicative of the heterogeneity observed across Member States. Countries such as Spain, Italy and Greece have a high rate of “slack” in their labor market. In contrast, countries such as the Czech Republic, Malta and Poland show a “tight” labor market with low rates of “slack”. The graph also shows the impact of the pandemic. In particular, all countries have a non-negligible percentage of the workforce which, although available, is not looking for work. This phenomenon may be due to reluctance to return to the workplace either due to health concerns or due to a wait-and-see behaviour, in order to find a better opportunity (the latter became feasible potentially due to the large targeted subsidies as well as the increase in households’ savings during the pandemic).

In Greece, the unemployment rate is far from the level of full-employment, although it has decreased recently, while many workers also resort out of necessity (and not by choice) to part-time jobs. Of course, in some industries the picture is different. For example, many businesses in the tourism sector find it difficult to fill jobs (given the offered salaries and working conditions). It is a fact that during the pandemic workers in tourism were significantly affected, with businesses completely suspending their operation. This inevitably led many employees to look for new opportunities in different sectors. However, the inability to attract employees back to tourism, in a phase of full recovery of the sector, also indicates the inability to provide competitive wages and working conditions.

Behind this potentially transitory phenomenon lies a more permanent trend. The growth model in tourism (“heavy industry” of the country, according to the cliché) is “cheap”: its main pillar is overexploitation of natural resources, low added value, low quality of services, low skills, low wages. Rising unemployment, deregulation of employment relations, and declining wages over the past decade have kept low-value businesses alive. The upgrade of the growth model, in accordance with the recommendations of the Pissarides Commission, is still to be seen.