On 8 October 2021, 136 OECD member states, accounting for more than 90% of the global economy, signed an agreement which radically changes the tax regime of multinational corporations.

The agreement consists of two pillars. First, multinationals will now have to pay taxes in jurisdictions where their business activity is concentrated, regardless of whether they have a physical presence there or not. The second pillar concerns a global minimum tax rate on corporate income at 15% to protect member states’ tax base.

There are multiple benefits stemming from the new tax regime. A direct effect is that governments can raise higher tax revenues, which is useful in this period of economic recovery after the pandemic. According to OECD estimates, the first pillar would lead to more than $125 billion being reallocated across jurisdictions. At the same time, the minimum tax rate at 15% would increase tax revenues by more than $150 billion globally each year.

Furthermore, the new agreement aligns the tax regime to modern business practices. Big corporations that market tech products or intangibles (e.g. drug patents, software etc.) have created subsidiaries in tax havens in order to avoid – within the letter of the law – the payment of taxes in the countries where they make most of their profits. In a relatively modest estimation of tax avoidance due to offshore activities, the IMF estimates that more than $600 billion are lost every year across the world.

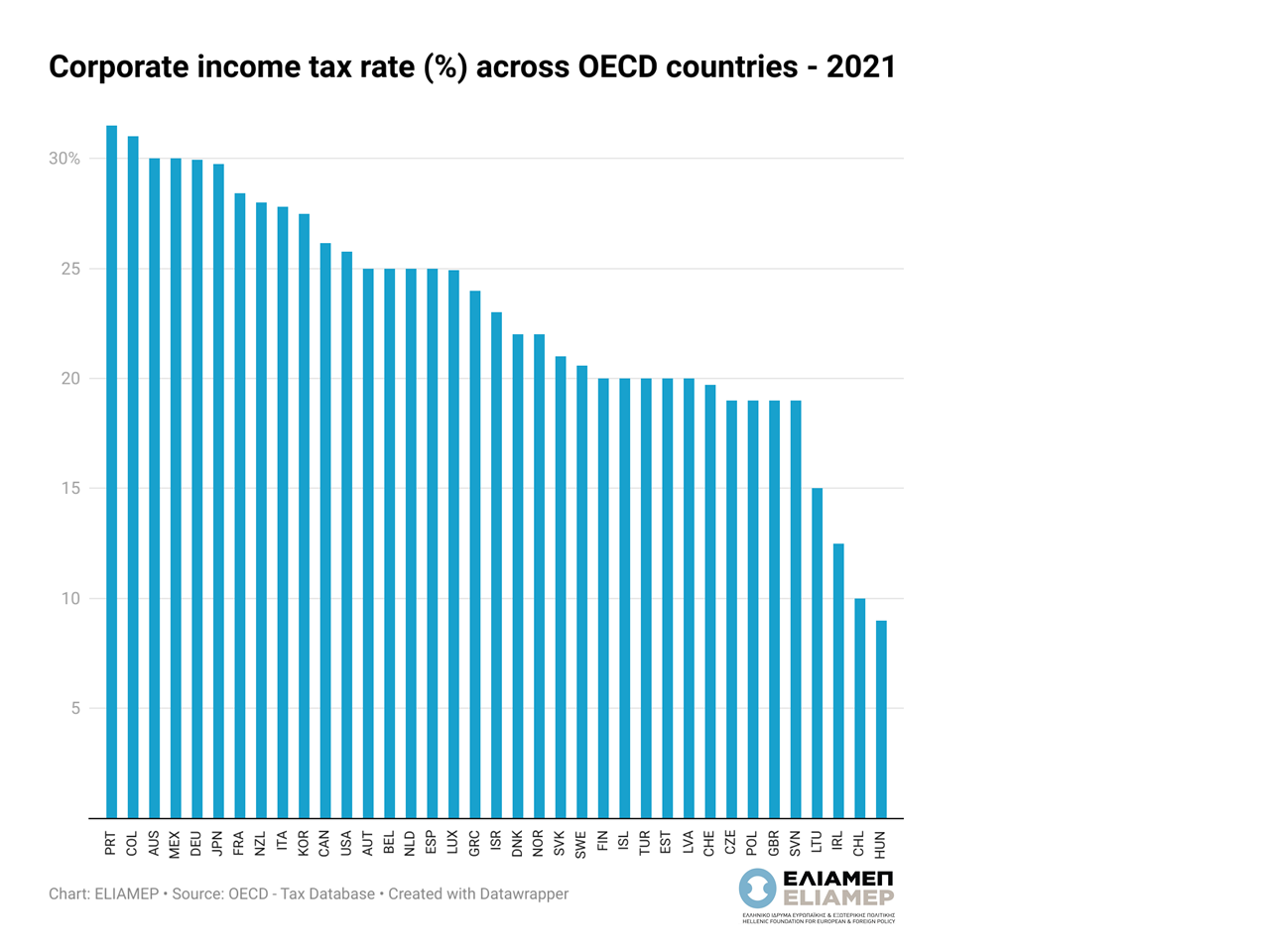

Last, the agreement significantly limits cross-country competition to attract multinationals by offering low corporate tax rates. Tax havens both in the developing and the developed world adopt low tax rates aiming to attract corporations’ holding companies and financial activities. Even within the EU, tax competition is rampant. As shown on the figure, corporate tax rates vary vastly. On the one hand, there is Portugal with a high tax rate (31.5%), on the other hand countries like Ireland and Hungary applying significantly lower tax rates (12.5% and 9% respectively).

The EU warmly welcomed the agreement. Benjamin Angel, director general of the directorate of direct tax and tax coordination at the European Commission, announced that a European directive will be published as quickly as possible to implement the agreement as it is. He also announced a complementary draft to promote tax transparency. In particular, this draft will require multinationals to publish not only their tax expenses but also the jurisdiction to which they pay them. Others have found the agreement did not go far enough. Oxfam noted that the global minimum corporate tax rate at 15% is significantly lower than the 20% to 30% proposed by the UN Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity (FACTI) Panel. Moreover, it highlighted that the agreement focuses mainly on the developed world, ignoring developing countries that largely rely on corporate taxes. According to a report by the OECD, African countries in 2018 levied more than 19.2% of their total tax revenues through corporate taxes, in comparison to only 10% in OECD member states. Oxfam estimates that the first pillar of the new tax agreement will allow developing countries to raise a mere 0.025% of their collective GDP.