When prices in the economy are rising too fast, labor unions rightly demand pay raises to maintain the purchasing power of their wages. History teaches us, that in periods of high inflation (1970s and 1980s) wage indexation sets in motion a vicious circle. Initially the rise in prices triggers demand for higher wages. The cost of higher wages is then passed on from employers that put up their own prices, creating a second round of rising prices – and so on. Thus wages and prices are trapped in a continuous upward spiral. This ultimately leads central banks to raise interest rates in order to cool the economy and calm inflation expectations. When demand decreases and the cost of borrowing increases, businesses shut down, unemployment increases and workers’ income weakens (including the unemployed).

In order to bring inflation under control, the ECB is expected to raise interest rates further. But for the time being, the conditions for an upward wage-price spiral in the Eurozone have not been created. As characteristically mentioned by the President of the ECB, Cristine Lagarde during a recent lecture : “We are not seeing the type of demand-led overheating that is visible in the United States and, despite a tight labour market, the risk of a wage-price spiral so far seems to remain contained.” She points out that the euro area is seeing an increase in inflation driven by two unprecedented shocks. These shocks have constrained global supply, but they have also shifted demand and led to a large and persistent inflation response: the pandemic that caused distortions in global supply chains, and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that drove up energy prices.

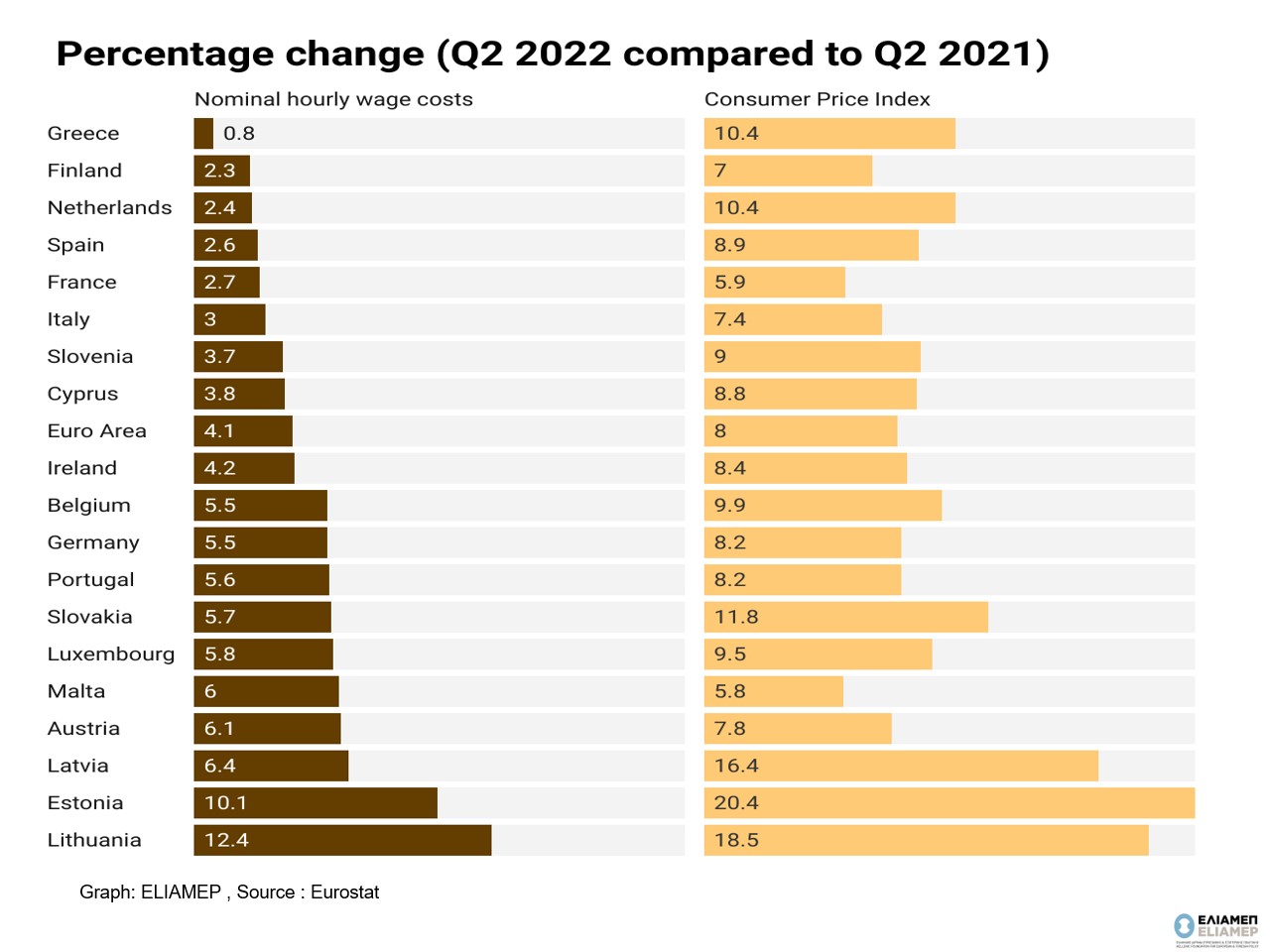

Some people believe that the upward spiral of prices and wages is an outdated discussion. According to data from the European Trade Union Confederation (ETUC), it is evident that the rate of coverage of collective bargaining has decreased in many EU countries, which reduces workers’ bargaining power, while at the same time employers have their hands tied by international competition. Looking at Eurostat data, in the Eurozone in the second quarter of 2022 the nominal increase in hourly wage costs (on an annual basis) was 4.1%, significantly lower than inflation (8%), which obviously implies a decrease in real wages. Nominal hourly wage growth lagged behind inflation in all Member States, but in some countries the purchasing power of workers was offset more than in others. In Germany, nominal hourly wages rose 5.5%, against inflation of 8.2%. In the other major Eurozone economies, nominal wage growth was lower: France 2.7%, Italy 3%, Spain 2.6%. In Estonia (10.1%) and Lithuania (12.4%) wage increases reached double-digit rates, but there inflationary pressures were stronger (20.4% and 18.5 respectively).

In Greece, the hourly wage cost, in nominal terms, remained almost stable, recording the smallest increase among the Eurozone member states (0.8%). At the same time, inflation for the same period exceeded 10%. According to a survey conducted in September 2022 for the General Confederation of Greek Workers (GSEE), in a sample of 1,500 workers in the private sector throughout Greece, 80% responded negatively to the question of whether they received a salary increase since the beginning of the year. Although Eurostat’s estimates may be revised upwards, and although the minimum wage has recently increased (2% in January and 7.5% in May), it is undeniable that wage growth in Greece is very slow. The combination of high inflation and stable wages suggests that it will be difficult to maintain the high levels

of private consumption that were reported in the first quarters of 2022 (which, despite the increase in exports, remains the driving force of growth for the Greek economy).