The rare earth elements (REE) are a set of metallic elements with unique electronic and magnetic properties which are used in a wide variety of applications. Their rarity stems mainly from the fact that mining and extracting them is extremely complex and costly. Because of their industrial value, the global demand for rare earths is constantly increasing.

The discovery of the large rare earth deposit in Sweden (over one million tonnes) is an important development: today the EU is almost completely dependent on China (98% of the EU’s rare earth imports are coming from China).

In general, the EU is vulnerable to critical raw materials supply squeezes. Raw materials form a strong industrial base, producing a broad range of goods and applications used in everyday life, in modern and green technologies and in electric engines. Without sufficiency in critical raw materials, the EU will not lead the green and digital transition and will not be able to develop its defense capabilities either.

One of the goals of the European Commission’s Critical Raw Materials Act is diversification and risk management of supply chains; this implies reducing EU’s reliance on countries such as Russia and China. This could possibly be achieved by pursuing ambitious partnerships with other countries with available recourses -with the precondition that imports are coming from environmentally sustainable and socially responsible rare earth mining projects- for example Chile (first in available lithium deposits), or Brazil (third in available rare earth deposits).

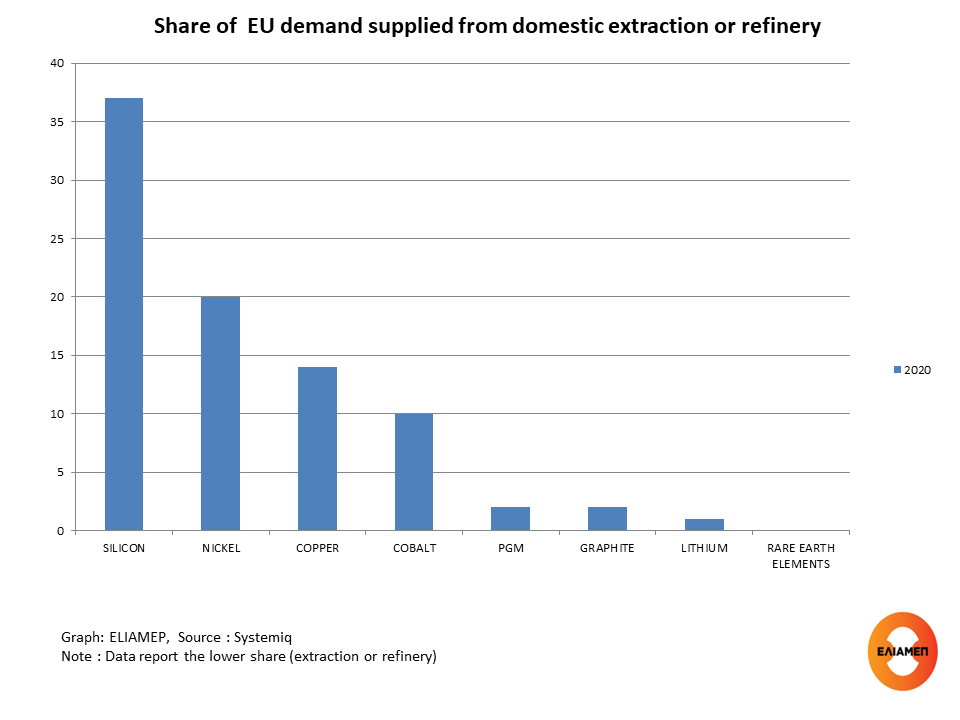

Beyond diversifying trading partners, EU also aims to bring parts of the supply chain back to Europe. As a EURACTIV article explains, achieving this goal is not easy for several reasons. Although Europe holds significant deposits of critical raw materials, many of them are not exploited. According to the Systemiq think tank, no rare earth elements are currently being mined or refined in Europe.

According to the graph (data refer to 2020), for lithium, graphite and PGM, the situation is only slightly better (at only 1%, 2% and 2% respectively). For cobalt, which is also included in the EU’s list of critical mineral raw materials, the EU mines 10% of domestic demand. Regarding silicon, although the EU mines 70% of domestic demand, it refines only 37%. For raw materials that are not yet in the official EU list, but are very important for the European industry (after the recent energy crisis new raw materials are expected to be in the list), such as copper and nickel, the EU only supplies 14% and 20% of the total demand from mining. One of the main problems is the delay in the permitting process for opening new mines, mainly due to environmental concerns. LKAB’s chief executive announced that the road to mining the newly-found deposits in Sweden is long and he explained it will be at least 10-15 years before they can actually begin mining and deliver raw materials to the market. Another potential solution is that the EU could promote the recycling of critical raw materials. But focusing on recycling, without any domestic mining, will not be enough on its own to meet the increasing demand.

The problem is that time is limited. According to the World Bank, global demand for critical raw materials is expected to increase 500% by 2050, causing prices to skyrocket. Also, the prices of rare earths and permanent magnets, where China has a quasi-monopoly, rose by 50-90% in 2021.

Meanwhile, as Commissioner Thierry Breton highlights, “For many of these essential raw materials, the global market will not be able to cater for the rapidly increasing demand.” That’s why the USA (with the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022), Japan or South Korea are all deploying sizable support and investments to lessen their dependence on the extraction, processing and recycling of critical raw materials.

The supply of raw materials can become again a geopolitical tool, as it has been in the past. In 2010, China slashed rare earth exports worldwide and entirely cut Japan off to pressure Tokyo to release a detained Chinese fishing trawler captain.The point is that in order for Europe to remain competitive in this global “race”, it needs to start dealing immediately with its biggest domestic challenges.