“Great Resignation” is the term Antony Klotz, professor of management at Texas A&M, coined for his prediction back in May 2021 about workers exiting en masse the labour market as a result of the pandemic. Recent statistics seem to validate his prediction: 4.3 million workers in the US resigned in August 2021.

Even though it is early to safely conclude anything about this phenomenon, researchers and analysts have delved into the issue, putting forward two explanations, structural and behavioural/psychological. On the one hand, restarting the economy after the pandemic, and a period of production and consumption suppression, induces businesses to search for employees in order to respond to the increased demand for goods and services. For instance, job postings in the US surged above 10 million. On the other hand, remote work during the pandemic, and the physical and mental tiredness brought about by the lockdowns, have led many employees to reexamine their priorities and reevaluate their work-life balance. A more relaxed approach to work, combined with an abundance of open vacancies, might motivate people to leave a job that no longer fits their expectations.

Is this a strictly American phenomenon, or has it crossed the Atlantic to reach European labour markets? In the UK, during August 2021, vacant posts reached a record high of more than 1 million, while according to another survey, 1 out of 4 employees plan to leave their job within the next 3-6 months. In Italy, an article in the daily il Sole – 24 ore cites estimates of 485,000 Italians having resigned over the period April – June 2021. In Germany, research by the ifo institute shows that 1 out of 3 German businesses have difficulty finding skilled employees. A Microsoft survey of 30,000 employees in 31 countries found that 41% plan to leave their job soon, while 46% would resign in favour of a more hybrid work environment.

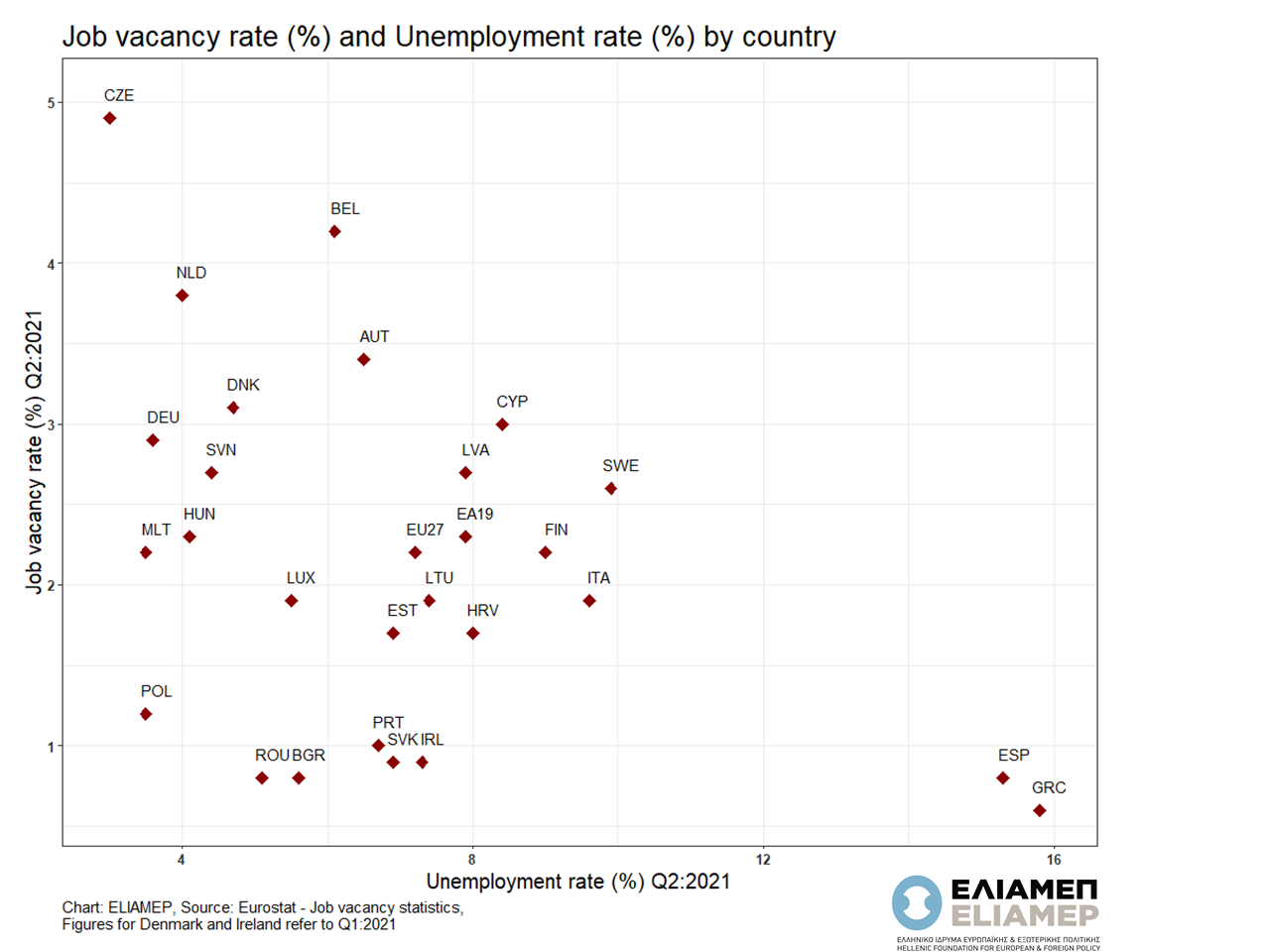

Low unemployment always implies more job vacancies, and vice versa. In the Figure we see that countries with high unemployment rates, such as Greece and Spain, have extremely low rates of job vacancies, while the opposite pattern is observed in countries with low unemployment such as the Czech Republic and Belgium.

It cannot be ruled out that the impact of the “Great Resignation” on the European economy is temporary. The US have only recently increased the generosity of income support to the unemployed via stimulus checks during the pandemic, setting a new standard for American social security. On the contrary, Europe has long ago put in place social security policies with special focus on unemployment benefits. In addition to that, permanent job contracts are much more widespread in Europe compared to the US, making it harder for employees to resign their (permanent) posts.

Despite the uncertainty as to how this phenomenon might develop, the pandemic has certainly changed the work environment. The hybrid working model that emerged during the lockdown entails both risks and opportunities. The question for public policy is how to mitigate the former while maximizing the latter.