In December, G7 (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, United Kingdom, United States) , EU member states and Australia agreed on a price cap ($60 per barrel price ) on Russian oil, which comes alongside the EU’s embargo on Russian crude oil imports. EU sanctions prohibit the purchase, import or transfer of seaborne crude oil and certain petroleum products from Russia to the EU. The restrictions apply from 5 December 2022 for crude oil and from 5 February 2023 for other refined petroleum products.

The aspirations of the cap are bold: to restrict Russian oil revenue while not increasing global oil prices. According to Bruegel, since 2006, over 60% of Russia’s federal budget revenues have been from oil and gas, with the contribution from oil around five times higher than that from natural gas. It should also be noted that according to Eurostat data, the average monthly value of European oil imports has increased from 16.1 billion euros in 2021 to 30.4 billion euros in the third quarter of 2022.

The European Union is a major source of income for Russia, precisely because of imports of fossil fuels, mainly natural gas and oil. In 2021, Russia was the largest supplier of oil to the EU (24.8% of total European imports in value terms). After the invasion of Ukraine, oil imports from Russia fell steadily despite the fact that total EU oil imports increased (from 36.9 million tonnes per month in 2021 to 41 million tonnes in the third quarter of 2022). Specifically, according to recent Eurostat data, oil imports from Russia decreased from 9.5 million tonnes per month to 7.5 million tonnes per month. At the same time, oil imports from other partners increased from 27.4 million tonnes per month in 2021 to 33.5 million tonnes per month in the third quarter of 2022.

The embargo carries risks. On the one hand, the oil ban divides the world in opposing trade coalitions and increases Russia’s dependence on the economies of Asia (mainly China and India). On the other hand, replacing Russian oil is not an easy task for the EU. It is a positive development that Norway’s oil production is expected to increase by 15% in 2023. It is estimated however, that imports from other areas such as the Middle East and Latin America would be needed to fully meet EU demand. According to a BBC article, persuading other oil rich nations such as Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Venezuela to increase production has so far been unsuccessful, as they have either remained neutral or backed Russia over the conflict with Ukraine.

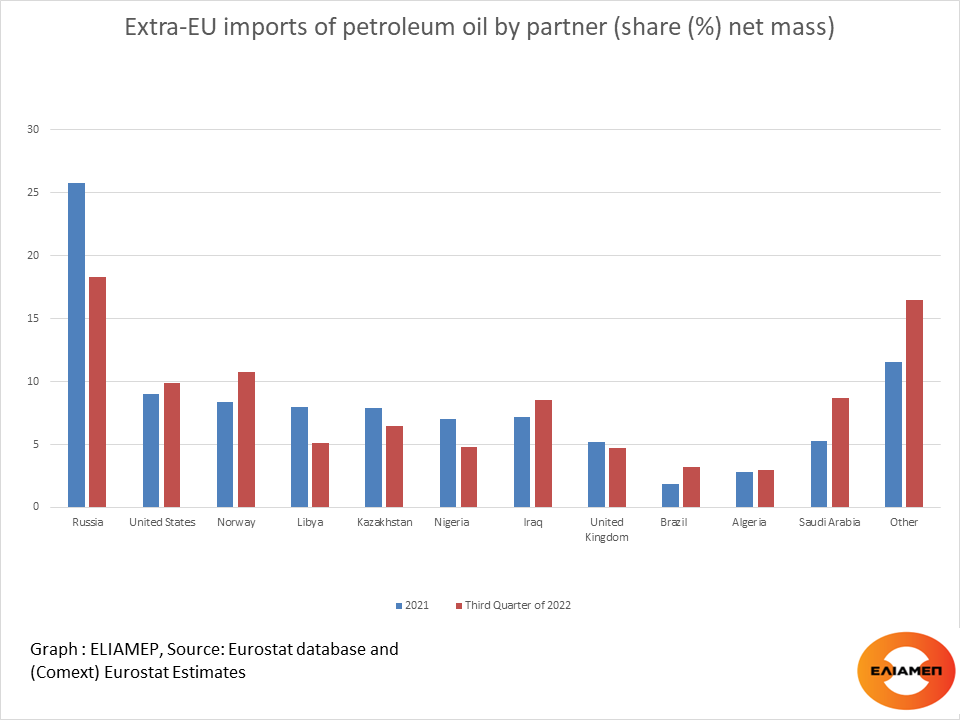

However, even before the full implementation of the embargo, Russia’s share of European oil imports has declined significantly. In 2021 Russia supplied 25.8% of total EU oil imports (in net mass). Norway (9%) and the United States (8.4%) followed at distance. In the third quarter of 2022, Russia’s share had decreased to 18.3% of total European imports, although Russia continued to be EU’s largest oil supplier.

In contrast, the share of other suppliers increased: in the third quarter of 2022, the USA was in second place (10.8% of the total amount of oil imported into the EU), and in third place was Norway (9.9%). Τhe shares of Kazakhstan, Libya, the United Kingdom, and Nigeria decreased slightly, while those of Iraq, Brazil, and Algeria increased. Imports from Saudi Arabia saw the most significant increase (from 5.3% in 2021 to 8.7% in Q32022 of total oil imports in net mass.)

The myriad of factors that interfere with oil markets make it difficult to draw any quick conclusions on the cap’s effectiveness. Some argue that as oil prices have fallen, there is no doubt that the price cap has worked. On the other hand, Russia’s threat to cut supply to countries that abide by the cap, the fact that consumption in India and the Middle East is proving more resilient than expected and China’s reopening could increase oil prices. All this means that the full effects of the West-Russia oil war are yet to be seen.