From February 5, EU countries are officially prohibited from importing refined petroleum products (mainly diesel) from Russia. According to data from the Bruegel think tank, about 40% of the petroleum products imported by the European Union in recent years came from Russia. In 2022 the EU imported from Russia about half a million barrels of oil products per day. Although the global macroeconomic slowdown is expected to slightly reduce EU demand for petroleum products, the EU will need to immediately increase its imports from other partners to fill the large gap left by the embargo. The first question that arises is: who might these new alternative suppliers be?

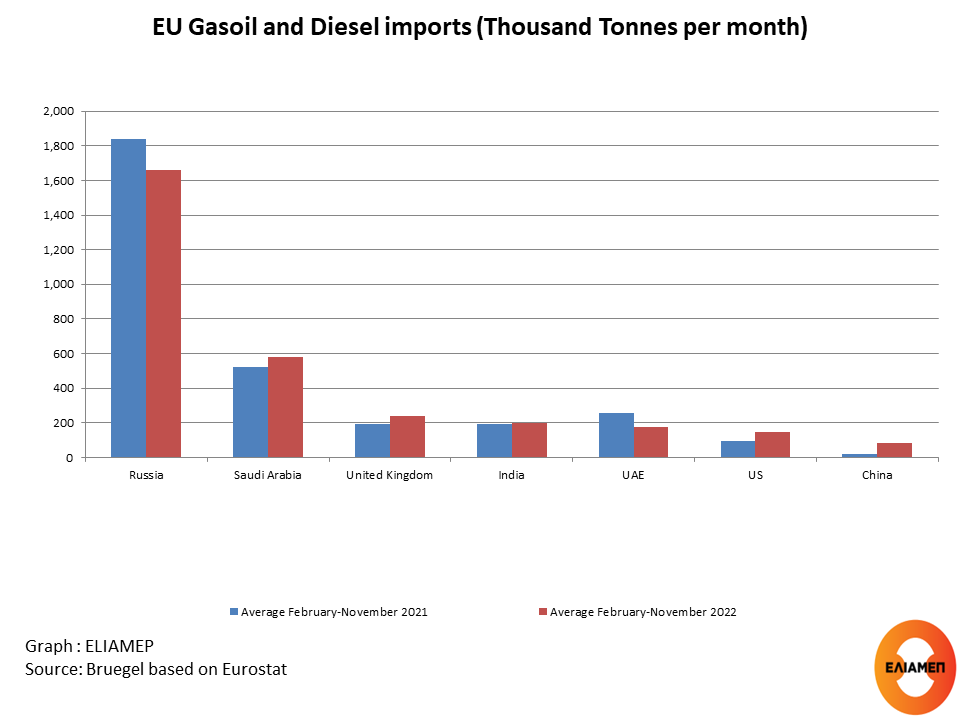

Although no one can predict how oil flows will look like in the coming months, 2022 has already started to signal some changes. Already before the embargo, average monthly imports of petroleum products (in tonnes) from Russia had decreased by 10%, comparing the ten months after the invasion of Ukraine (February-November 2022) with the same period of 2021. On the contrary, monthly imports increased from the US (58%), the UK (26%) and Saudi Arabia (11%). Imports from India remained almost sable (increasing only 2%), while EU petroleum imports from the rest of the world increased significantly (+40%). There was also a decrease in imports from the United Arab Emirates (-32%), a trend that is expected to be reversed in 2023, mainly due to the proximity especially with the Mediterranean countries. Abu Dhabi National Oil Co has already signed a deal to deliver diesel to Germany.

Finally, the amount of petroleum products arriving to the EU from China, although low (85 thousand tonnes, 2.3% of the total), rose significantly in the ten months of February-November 2022 compared to the corresponding period of 2021. While traditionally the policy of the Chinese government is to tightly regulate diesel export volumes, an increase in export permits in 2023 to the EU could fill the gap left by the embargo on Russian oil. But geopolitical and other (i.e. environmental) reasons may prevent the Chinese government from increasing its exports to Europe.

Recent data from Refinitiv confirm that post-embargo some of the 2022 trends continue. European countries replace Russian diesel supplies increasing imports from India, Saudi Arabia, China, Kuwait, Malaysia Togo, and China. Many of these countries are expected to invest further in refining to meet the needs of the European market. Refinery activity is already expanding in Saudi Arabia, Nigeria, Kuwait and China.

The second question that arises is whether and where will Russia sell half a million barrels a day of oil products that were previously exported to the EU. (In 2022 54% of Russia’s oil exports went to the EU.) Russia may enter new markets which will buy petroleum products in excess of their needs, in order to then redirect the surplus quantities to Europe. In other words, there is a case for the EU to re-import Russian crude from countries that either blend multiple crude oils in order to disguise origin, or that simply substitute Russian imports for domestic consumption. Countries that might adopt this practice include Turkey (which in 2022 imported 10% of Russian oil), Algeria, and Morocco, while larger trade routes could include Middle Eastern countries, such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, Africa or Latin America. Α Reuter’s article confirms that since early February 2023, Russia has been sending oil from its Baltic ports to Morocco, Algeria, Ghana, Tunisia and Brazil.

The result of the new EU embargo and price cap mechanism on Russian oil products is that two trading blocs are created: the countries that ban Russian oil products and those that continue to import them. A Reuter’s article explains that in order to import diesel to Europe from Asia and the Middle East requires large tankers with a capacity of 2 million barrels of oil. Moreover, shipping fuel from Russia into northwest Europe typically takes a week while cargoes from the East take up to 8 weeks on average. Therefore, the re-direction of petroleum flows will significantly increase transportation costs, which will also push up prices.