Around the world, the shutdown of the economic activity due to the coronavirus brought a drop in GDP and in the employment rate. In contrast, the end of the pandemic was followed by a recovery in GDP and employment rate. But the evolution of these two indicators was different in Europe and in the United States.

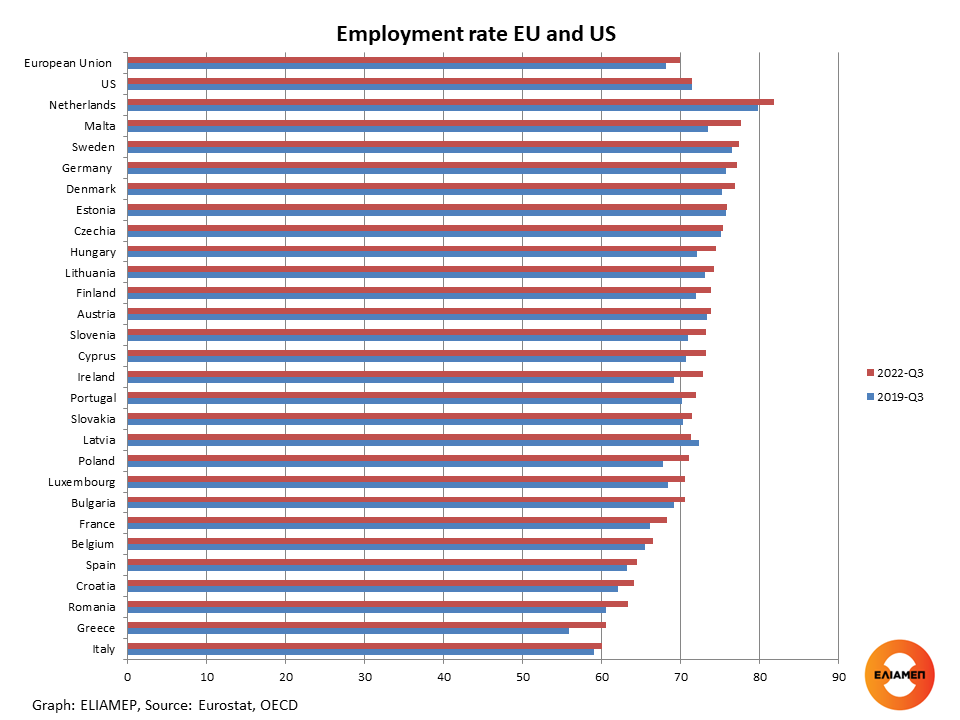

In particular in the EU, GDP fell more compared to the US, and recovered at a slower pace afterwards. However, employment followed the opposite course. Thus, in the third quarter of 2022 the employment rate (i.e. the number of workers as a percentage of the population aged 15-64) in the EU was 1.8 percentage points higher than in the same quarter of 2019, while in the US it remained slightly below the pre-Covid level. As a result of this, the difference in the employment rate between the EU and the US has fallen to 1.5 percentage points (from 3.4 in 2019).

Of course, there are big differences within the EU. In Italy, the worst performing member state, the employment rate was 11.4 percentage points lower than in the US. In contrast, in the Netherlands, the best performing country in the EU, the employment rate was 10.4 percentage points higher than in the US.

(Greece, with an employment rate of 60.6%, had the second-worst performance in the EU after Italy in the third quarter of 2022. But it was also the country with the most spectacular post-pandemic recovery, recording an increase in the employment rate of 4.7 percentage points units compared to the corresponding quarter of 2019.)

How to explain the rapid recovery of the labor market in Europe? The tradition of job retention programs such as the German Kurzarbeit has played an essential role in mitigating the pandemic’s impact on labor market. The main objective of these programs is preserving jobs at firms that experience a shock affecting business activity that is expected to revert in the near term. Employees are employed on reduced hours or do not work at all for a certain period, allowing the business to reduce payroll costs for the duration of the recession. In return, they get reimbursed partly or fully for the labor cost of reduced hours through an unemployment subsidy program (which is public), while keeping their job and returning to it when economic conditions improve. In this way, the employee is not burdened by the financial and psychological costs of the lay-offs, while the company doesn’t need to pay the costs of firing (as well as the costs future hiring and training of another employee).

During the pandemic, most European countries (and Britain) implemented some variation of job retention programs. The EU supported Member States with the SURE programme, which provided financial assistance of up to €100 billion in the form of loans to maintain employment. Recent studies, such as those by the think tank Bruegel and the research institute Eurofound, provide details on the job retention programs implemented in each member state.

In contrast, in the US the focus was on incentives for businesses to keep jobs (through the paycheck protection program), increasing unemployment benefits (which are normally less generous than in Europe), as well as lump sums payments to all (which greatly benefited low-income individuals and households).

In summary, the employment policies implemented in the EU – focusing on preserving jobs –have so far proved more successful. President Biden’s economic policy may lead to an employment recovery in the coming years in the US as well. In any case, the EU and its Member States have successfully responded to the challenge of the pandemic, maintaining high levels of employment and social cohesion.