The coronavirus pandemic is an unprecedented health crisis with tragic humanitarian consequences. Effective tackling of the pandemic, in both health and economic terms, requires an ambitious fiscal approach. Such an undertaking is a challenge, whose scale is magnified for the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), which experienced a deep economic crisis in recent years. The crisis has left a legacy of problems in some of the member states that have not yet been adequately addressed, principal among them, the high level of public debt. This creates is a ‘doom loop’ for these countries, as their indebtedness undermines their ability to combat the pandemic, and at the same time a fiscal intervention of the magnitude required, would undermine the sustainability of their public finances further, hampering their future economic potential, after a decade of limited or no growth. During the previous crisis, despite a major reform effort, the EMU failed to create common fiscal and debt instruments to help her navigate through a future major economic shock. Alas, the shock came earlier than anticipated and exceeds by far any adverse scenario previously considered. Now, in the midst of another crisis, European leaders try to find some common ground, but old divisions have risen again, pitting supporters of fiscal solidarity against fiscal conservatives, which resist unconditional credit lines and/or mutualization of debt invoking the risk of moral hazard. The stakes are high; if the EU fails to deal effectively with a major crisis for the second time in a decade, the consequences for the Eurozone could be dramatic.

You may find here the full text of the Policy Brief by Dr Dimitrios Katsikas, Senior Research Fellow, Head of the Greek and European Economy Observatory.

Introduction

“… Such an intervention constitutes a fiscal challenge, whose scale is magnified for the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU)”

The coronavirus pandemic is an unprecedented health crisis with tragic humanitarian consequences. At the same time, it is a major economic challenge, particularly for Europe, which now stands at the heart of the global pandemic. In these circumstances, fiscal policy becomes a crucial instrument at the hands of authorities; effective tackling of the pandemic, in both health and economic terms, requires an ambitious fiscal approach, for at least three reasons:

(a) to support and strengthen health systems and other government agencies in order to control the transmission of the disease and treat patients.

(b) to support the economy -households and businesses- as economic activity plummets during the crucial period of ‘social distancing’ measures, increasingly adopted across countries.

(c) to address the ‘hysteresis effects’ once the health crisis is over, caused by the disruption in the economy, for example due to increased unemployment, and from the return to policy normalcy, when deferred tax, insurance and debt obligations will have to start being paid again.

Such an intervention constitutes a fiscal challenge, whose scale is magnified for the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), which experienced a deep economic crisis in recent years. The crisis has left a legacy of problems in some of the member states that have not yet been adequately addressed, principal among them, the high level of public debt. This creates is a ‘doom loop’ for these countries, as their indebtedness undermines their ability to employ the fiscal resources necessary to combat the pandemic, and at the same time a fiscal intervention of the magnitude required, would undermine the sustainability of their public finances further, hampering their future economic potential, after a decade of limited or no growth. During the previous crisis, despite a major reform effort, the EMU failed to create common fiscal and debt instruments to help her navigate through a future major economic shock. Alas, the shock came earlier than anticipated and exceeds by far any adverse scenario previously considered.

Under stress with no bazookas

“EU leaders pinned their hopes on a much anticipated ‘catching-up’ process and imbalances relied on ‘market discipline’ to prevent the emergence of large fiscal or other macro-economic imbalances”

After the outbreak of the global financial crisis, and in the midst of the eurozone debt crisis that followed, the EMU embarked on an ambitious reform effort. The pre-crisis economic governance of the EMU, rested on a political deal, whose economic rationale was questionable. Against a background of low labour mobility and highly diverse national economies, EU’s monetary union was based on institutionally weak fiscal and macroeconomic pillars and lacked a supranational fiscal capacity, which could perform a stabilization function and coordinate an EMU-wide fiscal stance. EU leaders pinned their hopes on a much anticipated ‘catching-up’ process and relied on ‘market discipline’ to prevent the emergence of large fiscal or other macroeconomic imbalances, in view of the no-bailout clause included in the Maastricht Treaty.

Unfortunately, markets dismissed the no-bailout clause alleging instead, that in order to preserve the monetary union, a way would be found to help member states in crisis. On this assumption, increased financial integration instead of disciplining member states, relaxed the funding constraints of weaker economies, allowing the emergence of large fiscal deviations (e.g. in Greece), and encouraging complacence based on precarious fiscal revenues in countries like Spain, Ireland and Cyprus.[i] When the crisis hit, the decentralized ‘individual responsibility’ governance of the EMU, had no institutional tools to handle it, forcing crisis-hit countries to engage in a painful adjustment process and the EU to launch a major reform effort, amid economic disorder and political recriminations.

“…the desire to limit moral hazard dictated the conditionality that accompanied the bailout programmes”

Unsurprisingly, and notwithstanding the progress made, the outcome has not been entirely satisfactory. The reform effort was dominated by a pre-occupation with ‘moral hazard’, i.e. the risk that debtor countries would use the loans they received (or the ability to borrow through a common debt instrument -a Eurobond), to avoid implementing politically costly, but economically necessary, reforms. This could potentially result in permanent fiscal transfers to those countries, leading to a ‘transfer union’ at the expense of the creditor member states. The desire to limit moral hazard dictated the conditionality that accompanied the bailout programmes, but also the design of the reforms, with a view to enhancing supervisory and control mechanisms, while minimizing the commitment of resources and the delegation of powers at the supranational level.

Accordingly, the main reforms in the area of fiscal governance comprised mechanisms of enhanced national fiscal discipline and surveillance. The coordination of fiscal policies remained an institutionally unrealized objective; perversely, coordination did take place in an ad hoc manner, by member states’ voluntary or imposed adherence to austerity. Supranational fiscal instruments and funding were in effect absent,[ii] and the stabilization function remained at the national level. Moreover, proposals for the creation of a European safe asset did not progress, despite the fact that it could provide an effective mechanism for restoring access to funding for countries undergoing a crisis and prevent uncertainty-induced contagion to other member states (Gilbert et.al. 2013). In a sense, the new fiscal governance is a reinforced version of the pre-crisis fiscal framework; as a result, the EMU lacks both fiscal and debt supranational instruments to deal with a new crisis.

“The most important factor however has been a political economy struggle”

Despite the increasingly shared acknowledgment that the ‘reformed’ fiscal governance remains incomplete, ineffective and therefore in need of further reform (refs), and despite a series of proposals put forward by European institutions in that direction, progress has been slow. One explanation for this is that economic recovery weakened the crisis’ catalytic pressure for reform. The most important factor however, has been a political economy struggle that continues to pit fiscal conservatives that preach against the risk of moral hazard against supporters of fiscal solidarity. Recent years’ economic recovery has not changed the terms of this struggle as the eurozone crisis casts a dense and long shadow. Its legacy includes non-performing loans, high levels of public debt and output gaps. Dealing with the adverse legacy of the crisis for a number of member states, requires further adjustment, which comes at substantial economic and political cost. The distribution of this cost is a highly political issue and has divided the union, between proponents of risk reducing and risk sharing options.

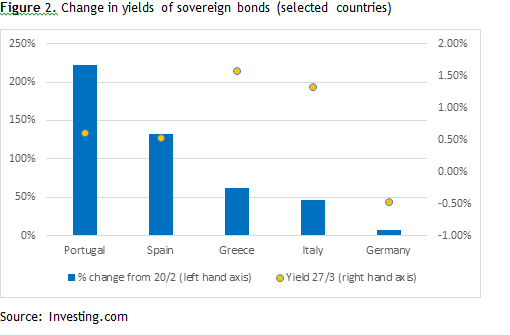

Finding a way to overcome this divide has acquired new urgency in view of the coronavirus pandemic. Italy, which is currently being tested by the pandemic like no other EU country, has a public debt of 136% of GDP and the fourth highest rate of non-performing loans in the Eurozone (7.33%), while in countries such as Greece, Portugal and Cyprus things are even worse. The scale of the challenge was quickly perceived by the markets that put pressure on the government bonds of these countries. In the month preceding the ECB’s decision to launch an emergency purchase programme, Italy’s bond yield increased by 1.45 percentage points, Spain’s by 0.74 percentage points and Greece’s by 2.69 percentage points (Figure 1). By contrast, Germany, ranked 5th globally in terms of the number of coronavirus cases, saw the yield on its 10-year bond fall further.

As the crisis spreads throughout Europe, EMU’s fiscal intervention could literally be a lifeline for countries facing budgetary constraints and increased funding costs. The urgency of this realization becomes more pronounced due to the unfortunate coincidence that the first major outbreaks are in countries that carry a legacy of problems from the previous crisis, such as Italy and Spain. Given that the inability to treat the virus in one country undermines the collective effort to tackle the virus, it is clear that strengthening member states’ budgetary capacity to deal with the crisis is in the interests of the entire union.

[i] The large capital inflows led to macroeconomic imbalances, including the creation of real estate bubbles in these countries; the fiscal windfalls related to these bubbles improved the fiscal balance, hiding weaknesses in securing stable and sustainable fiscal revenues.

[ii] During the crisis the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) was established to provide funding to countries that lose access to the international markets. However, the ESM operates on the basis of strict policy conditionality, aimed at restoring imbalances at the national level. Conditionality tends to work in a procyclical manner, intensifying in the short-term the negative effects of the economic shock and, as experience has shown, producing major political aftershocks; understandably it is not an attractive option for member states (see next section).

EMU’s reaction

“… In order to support bank liquidity, the ECB announced a new longer-term refinancing operations programme”

What has been EMU’s reaction to this unprecedented situation? The first moves came from the European Central Bank (ECB), which on the 12th of March adopted an array of measures to enhance liquidity and sustain credit in the markets, and to support the prices of assets (including sovereign bonds). More specifically, the ECB added €120 billion to its existing, €20 billion per month, Asset Purchasing Programme (APP) to support the prices of assets. At the same time, in order to support bank liquidity and the provision of credit to the economy, the ECB announced a new longer-term refinancing operations (LTROs) programme, at the very low (negative) deposit facility rate of -0.50%. Moreover, it announced an expansion of the targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTRO III) programme to start in June, which includes an increase in the volume of funds that banks can borrow for extending loans to the economy, by €1 trillion, and an improvement of terms, including a reduction of the interest rates that bank can borrow up to -0.75%. Along the same lines, the ECB’s Supervisory Board, relaxed some of the capital requirements for banks, providing capital relief of up to €120 billion.

“The ECB’s new president refrained from re-affirming the ‘whatever it takes’ approach of her predecessor”

Despite the measures market turmoil increased, when in an interview, the ECB’s new president refrained from re-affirming the ‘whatever it takes’ approach of her predecessor. Her remark, meant to put pressure on the EMU to step up with fiscal measures, sent Italian and other south European countries’ bond yields, already on the rise, soaring (see Graph 1). The ECB responded on the 18th of March with the €750 billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), which complements its existing APP programme. Compared to the APP programme, the PEPP enjoys increased flexibility in terms of asset class, maturity and country limits; for all intents and purposes it is a limitless quantitative easing programme intended to offer relief directly to sovereigns and non-financial corporates.

“On the national front, governments have introduced an array of fiscal measures”

On the fiscal side, the European Commission proposed to mobilize €65 billion through a €37 billion “Corona Response Investment Initiative”, employing funds from the European Structural Investment Fund (ESIF), and another €28 billion redeploying structural funds. The European Investment Bank (EIB) also proposed to mobilize €40 billion through various mechanisms, mostly in the form of loan guarantees. On the national front, governments have introduced an array of fiscal measures, whose size is on average 2% of GDP, while liquidity supporting measures (e.g. states guarantees for loans to businesses and tax deferrals) have reached on average 13% of GDP (Centeno 2020). The adoption of these measures was facilitated by the Eurogroup’s decision on the 16th of March to exclude these measures ‘when assessing compliance with the EU fiscal rules, targets and requirements’, making use of the Stability and Growth Pact’s (SGP) flexibility. Finally, on the 24th of March the Eurogroup endorsed the European Commission’s proposal for the activation of the ‘general escape clause’, which effectively suspends the fiscal rules for the EMU, providing maximum degree of fiscal flexibility for the member states to deal with the health crisis.

Is it enough?

“The EMU has taken some new bold steps; unfortunately they have been taken along an old, well-trodden path”

The EMU has taken some new bold steps; unfortunately, they have been taken along an old, well-trodden path. On the one hand, the ECB continues its activism, bearing once again the main burden of response, as it had also done with the previous crisis. The PEPP had a dramatic effect on the yields of southern member states; a further decline was recorded when it became known that for the PEPP, the ECB will relax country purchase limits (Graph 1). In effect the PEEP secures member states’ access to markets and therefore their ability to keep borrowing to finance the struggle against the coronavirus and its economic impact.

On the other hand, the fiscal response has been subdued; the supranational measures announced by the European Commission and the EIB are well below €100 billion, less than 0.5% of EU’s GDP. This compares poorly to US’ $1.2 trillion fiscal intervention, bringing back memories of a delayed response (at that time on the monetary front) to the global financial crisis. The response has been bolder when it comes to national fiscal flexibility; the activation of the general escape clause is an unprecedented move as such. Still, it follows the same decentralized, ‘individual responsibility’ rationale; the idea is to allow states to deal with the crisis as they see fit, within the limits of their fiscal and macroeconomic circumstances, without committing substantial common resources. While access to markets for sovereigns has been largely secured by ECB’s moves, it may not be enough.

“While access to markets for sovereigns has been largely secured by ECB moves, it may not be enough”

The projections for economic growth are particularly gloomy; for the 2nd quarter of 2020 growth in the EMU could drop by as much as 24% (Deutsche Bank 2020). In such circumstances, the funds required are truly unprecedented. Pilling up massive new loads of debt in a recession is likely to lead to serious sustainability problems in the medium-term for sovereigns that are already heavily indebted, particularly when yields continue to be elevated, despite ECB’s intervention, and will likely increase further if things get worse (Figure 2).

“Ideally, the organization of a common debt instrument would differentiate between the receiving and payments keys”

“However, the way the ESM normally works is through adjustment programmes, well-known from their use during the previous crisis”

What is needed therefore, is either a fiscal mechanism able to deliver substantial amounts of funds at very long maturities and very low cost, or a common debt instrument, which could perform a similar function. Ideally, the organization of a common debt instrument would differentiate between the receiving and payment keys; in other words, repayment would be based on a pre-determined criterion like the size of the economy or the ESM’s capital key, but funds would be directed according to the severity of the health crisis (see Claeys and Wolff 2020 for more details). Such a solution would increase available funding for countries that need it most, without increasing their debt burden at the same rate. Given that such an instrument could be designed as a one-off emergency solution, fears of a transfer union should not come into play.

“At this time the outcome is uncertain”

However, progress on such proposals is not forthcoming and the divide between the two camps has become more visible than ever before. On the 25th of March nine European leaders, representing among others, the vulnerable countries of the South, sent a letter to the European Council President asking for a ‘common debt instrument’. The proposal was rejected by Germany and its allies at the European Council meeting the next day; debt mutualization continues to be an anathema for these countries, despite their acknowledgment that the circumstances are unique and desperate. The only solution being considered by the Northern block is the use of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). However, the way the ESM normally works is through adjustment programmes, well-known from their use during the previous crisis. At this stage, it is obvious that no country, especially those that were at the heart of the previous crisis, would be prepared to implement new adjustment programmes, which would require austerity policies to restore debt sustainability.

The European Council invited finance ministers to present proposals within the next two weeks; at this point it seems that the only solution being discussed by Germany is some use of the ESM; the negotiation will be about finding ways to do this without imposing strong conditions for the use of funds and if possible to avoid the related stigma, by for example, making the credit line available to all member states. It remains to be seen whether a solution could be agreed that entails no substantial conditionality and attractive enough terms to make a difference.

At this time the outcome is uncertain; the distance separating the two sides is significant and it seems increasingly likely that we will have a repetition of the highly ineffective ‘kicking the can down the road’ approach that prevailed during the debt crisis. Unfortunately, ECB’s actions while undoubtedly helpful, indirectly facilitate this approach, by relieving for the time being the pressure in the sovereign bond markets. Going down this road, would be a major mistake. The speed of reaction to this crisis is an extremely important parameter – the longer the delay, the longer the duration and the cost of the crisis.

“If the EU fails to deal effectively with a major crisis for the second time in a decade, the consequences could be dramatic”

The handling of the debt crisis dealt a huge blow to the credibility of the EU. The coronavirus crisis could be an opportunity to regain the trust of European citizens. On the other hand, if the EU fails to deal effectively with a major crisis for the second time in a decade, the consequences could be dramatic. Given that Euroscepticism has become entrenched in many societies after the debt crisis, that the current crisis’ casualties will be primarily humanitarian, and that according to projections we are in for an unprecedented recession, a new failure could turn the coronavirus pandemic into a Eurozone existential crisis of unparalleled proportions.

References:

- Centeno Mário (2020) ‘Remarks following the Eurogroup videoconference of 24 March 2020’, available at https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/03/24/remarks-by-mario-centeno-following-the-eurogroup-meeting-of-24-march-2020/

- Claeys, G. and B. G. Wolff (2020) ‘COVID-19 Fiscal response: What are the options for the EU Council?’ Bruegel Blog Post, available at https://www.bruegel.org/2020/03/esm-credit-lines-corona-bonds-euro-area-treasury-one-off-joint-expenditures-what-are-the-options-for-the-eu-council/

- Deutsche Bank (2020) ‘Deutsche Bank Economists forecast “severe recession” due to Covid-19’, available at https://www.db.com/newsroom_news/2020/deutsche-bank-economists-forecast-severe-recession-due-to-covid-19-en-11507.htm

- Gilbert, N., Hessel, J. and Verkaart, S. (2013) ‘Towards a Stable Monetary Union: What Role for Eurobonds?’, DNB Working Paper No. 379, May, De Nederlandsche Bank NV, Amsterdam.