The recent crisis in Evros brought back to the fore the issue of immigration and Turkey’s role in its instrumentalization.

The EU-Turkey Statement has not had the expected outcomes. Rather it showed that prevention policies and the outsourcing of migration management strengthens transit countries such as Turkey, without resulting in a a steady reduction in flows. Greece remains a country that bears a disproportionate burden of responsibility due to its geographical location. At the same time, it has delayed in the planning of a holistic immigration policy, which should aim, among other things, to ensure human living conditions, substantial access to asylum and result in the integration of those who will remain in the country. COVID 19 will bring about significant socioeconomic changes globally as well as impact human rights.

Practices of the past do not necessarily fit for the new reality and this is the biggest challenge for Greece and the EU; a willingness to move forward by investing on migration within Europe and beyond. It will not be easy, and it will come at a high financial (and likely political) cost. The pandemic makes any long-term commitments seem impossible, however the alternative scenario, of deterrence and outsourcing is already proving insufficient. Balancing the scales is a challenge which the EU cannot afford to lose.

You can find here the pdf version of the Policy Brief by Dr. Angeliki Dimitriadi, Senior Research Fellow, Head of the Migration Programme of ELIAMEP.

The years before

In March 2016, EU leaders and Turkey announced through a joint statement that an agreement had been reached regarding the migrants transiting from Turkey to Greece. A key component was that all new irregular migrants crossing into Greek islands as from 20 March 2016 would be returned to Turkey. Arrivals would be entitled to apply for asylum and while a decision was pending, they would be detained in the Reception and Identification centres (RIC), also known as the hotspots. Returns would include those without a protection claim and those whose claim was deemed inadmissible or unfounded. The geographic restriction on the islands and RICs, requested by Turkey and imposed by the government at the time, sought to ensure returns to Turkey took place quickly[1].

“The core rationale of the Statement was that it would function as a deterrence for those seeking to undertake the journey to Europe”

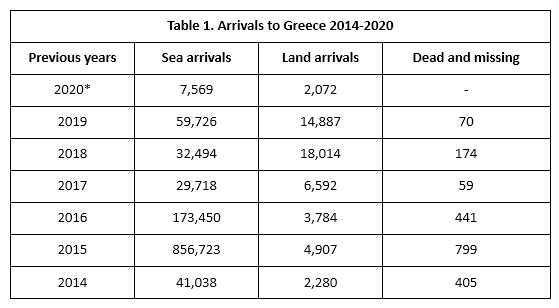

The core rationale of the Statement was that it would function as a deterrence for those seeking to undertake the journey to Europe. Aware that they would be trapped on the Greek islands in deplorable conditions, and returned to Turkey, asylum seekers would seize crossing the maritime border. In practice this did not happen. Though numbers have reduced over the years, migration remains a constant in the Greek Turkish maritime and land border (see Table 1). An increase in the summer of 2019 was followed by a decrease in arrivals in the aftermath of the crisis in Evros in the winter of 2020. Migration remains a constant.

*Until April 14 2020. Source: UNHCR Operational Portal: Refugee Situations: Greece, https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5179

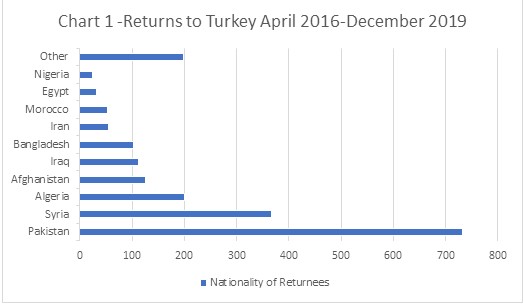

Returns to Turkey have also not taken place as envisaged. From April 2016 and until December 2019 a total of 2,001 persons have been returned (see Chart 1 below). Of those returned, 42% had their case rejected on appeal with another 24% opting out of the asylum process (expressed no will to apply).

There are multiple reasons for the delays. The attempted coup in Turkey in the summer of 2016 brought returns to a halt while uncertainty lingered over the domestic situation in Turkey. Many stranded in the hotspots were considered vulnerable due to gender, age, and health issues, placing them outside the return framework and eligible for transfer to the mainland. Many cases were deemed admissible on first instance or an appeal but there have also been huge delays in processing asylum claims.

Source: UNHCR Returns from Greece to Turkey https://reliefweb.int/report/turkey/returns-greece-turkey-31-december-2019

“The asylum service became operational in 2013, designed to process approximately 20,000 asylum applications each year. In 2018 alone, the service received 66,969 new applications.”

This is due to the high number of applications and the limited staff in comparison. The asylum service became operational in 2013, designed to process approximately 20,000 asylum applications each year. In 2018 alone, the service received 66,969 new applications. The European Asylum Support Office stepped in to assist in the admissibility assessment on the islands, however it has received criticism of its conduct, which raises questions on the Agency’s procedures. A formal complaint[2] was launched with the European Ombudsman on the basis that the interviews conducted by EASO, arguing that the Agency denied asylum seekers a fair hearing and the chance to adequately present their case. Though the Ombudsperson closed the inquire into EASO, it acknowledged serious concerns regarding the process and urged the Agency to set up a complaint mechanism as a matter of priority.

Despite assistance, at the end of 2019 the asylum’s service had a backlog of 68,000 asylum requests. In practice this means that asylum applicants wait for years to receive a decision and remain stranded on the islands.

Asylum is not the only element that is under strain. The centres on the five islands of northern Aegean have been designed to host at maximum 6,000 individuals. The numbers quickly exceeded capacity with conditions consistently deteriorating rather than improving. In 2018, the Greek authorities transferred 29,000 persons to the mainland primarily women and children, most deemed vulnerable. Vulnerabilities increase (and in many cases develop) as a result of the sub-standard conditions in the facilities. As more people continued to arrive, the transfers do not reduce the total number of asylum seekers in the hotspots.

A (not so) new strategy

On July 7, 2019 national election results brought the party of New Democracy (ND) in power under the leadership of Kyriakos Mitsotakis. The Prime Minister had already advocated in favor of the Statement and strengthening returns to Turkey during the election campaign[3].

Initially the government undertook the transfer of 14,750 persons from the islands to the mainland between September 2019 and January 2020. A positive step but with roughly 40,000 new arrivals entering the maritime borders in the same period it was not enough to reduce numbers in the hotspots. The continuous influx coupled with the containment policy on the islands brought local communities to boiling point. The presence of migrants in squalid conditions living in fields around the hotspots is a relatively new experience for the islands and has created problems.

The containment policy has also come at a cost as public infrastructure is unable to cater to the needs of migrants and residents. The government proposed plans to construct new detention centres but faced significant opposition from residents who fear the permanence of the centres. Faced with protests, roadblocks, and threats of legal action the government sought to present the closed centres as a solution to appease locals but also increase returns to Turkey. In this, Greece is stuck between a rock and a hard place. Transferring people to the mainland, even if facilities were created, would mean they would not return to Turkey. On the other hand, the current policy violates the dignity of asylum seekers and has resulted in a humanitarian crisis in the islands, placing an unfair burden to the local population.

In parallel with the discussion for closed centres, the law on asylum changed in late 2019. The bill introduced procedures and deadlines impossible to meet and focused on punitive measures for asylum applicants. UNHCR noted that the bill “reduces safeguards for people seeking international protection and will create additional pressure on the overstretched capacity of administrative and judicial authorities.”[4]

A new bill was submitted for review in April 2020, making this the second legislative change in less than a year. Once it passes, it will reduce access to legal assistance and facilitate the detention of asylum seekers in ‘controlled’ centres, making access to asylum more restricted.

What has yet to be presented is a strategy for the social and economic integration of the 50,000 persons in the mainland who will be staying in the country. This is more crucial, factoring the post COVID-19 socio-economic environment that will emerge. Rather, deterrence, detention and return make up the new policy on migration. In this, the strategy resembles the policies of 2012-2014, yet deterrence as a policy was not particularly effective at the time. Rather the government at the time, failed to establish a continuous and humane system of returns- a failure most EU member states share and a problem that remains to this day. It also showed that administrative detention, did not deter people from coming.

Numbers will ebb and flow depending on events and triggers in the periphery. They rarely can be effectively controlled by deterrence measures. Yet this is a lesson that Greece and Europe refuses to learn and the crisis in Evros only strengthened the belief in deterrence as the way forward.

Becoming Europe’s ‘shield’

Towards the end of February 2020, thousands of refugees moved towards the Greek-Turkish borders of Evros. In response, Greece closed its borders, with reports coming out of escalated practices of pushbacks, teargassing, and arrests of new arrivals. Widespread misinformation that the border was open resulted in thousands reaching the Greek Turkish land border hoping to cross through. Among them, organised groups sought to create chaos and tension at the border. The decision of the Greek government to suspend access to asylum, in violation of international law, is a cause for concern. Greece announced it was invoking article 78 (3) to justify the suspension of asylum, however it would require a proposal is submitted by the Commission and agreed by the Council.

Though the right to defend one’s borders is unchallenged, access to asylum is a fundamental right guaranteed by both European and International Law. Maintaining the rule of law, especially in times of crisis, is the measure and strength of the EU and its member states. Access to asylum has since been-in principle- restored, however the government response raises questions about the way forward, as it fundamentally strengthened the voices of those who support a ‘fortress Europe’.

The crisis in Evros was framed as a border issue. Coated in nationalistic rhetoric, the public discourse facilitated the rise of vigilant groups at the border and on the islands. Attacks took place against migrants, NGOs and humanitarian workers and journalists. An NGO warehouse storing supplies for asylum seekers was set on fire on Chios. The discourse around the crisis in Evros focused on one aspect of the issue; the organised attempts to break past the border by specific groups. While these were ongoing, asylum seekers tried to find points of entry and in many cases were summarily returned to Turkey.

Events in Evros are part of a broader issue, that begins in Europe and extends to the countries of origin and transit. It has to do with legal responsibilities, norms, and values. During the refugee crisis, Europe proved unable and unwilling to showcase solidarity that extends beyond financial assistance. Revision of the Common European Asylum System stalled due to the refusal of various Member States to accept proposals for a Dublin reform that would incorporate a permanent redistribution mechanism. Discussion shifted from protection to deterrence and how to ensure fewer people reach Europe. Framed as a humanitarian argument- saving lives by preventing journeys- the reality is that deterrence, and absence of alternative pathways of entry, harm those who need protection the most.

For years, the EU has tried to assist Greece in functioning as Europe’s “shield”, i.e. carrying the burden of reception, asylum processing and returns. It has undertaken similar efforts with the countries in the immediate neighbourhood and beyond, not always to their benefit. The focus on returns and border controls addresses only one element in the management of migration. Shared positive recognition across the EU, a permanent redistribution system and a holistic migration policy that does not focus only on reducing arrivals through deterrence and punitive measures but through fostering strong relations with the countries of origin are all elements that are missing.

“…the EU has strengthened the negotiating position of transit countries, by continuing to outsource migration management, offering financial assistance in exchange for the containment of migrants.”

In this, Turkey has and will continue to play a crucial role. The instrumentalisation of migration is not new. Turkey, unlike its European counterparts, grasped quite early the possibilities offered through the incorporation of migration in its foreign policy. This is the strength of transit countries; to be able to utilise their geographic position in the migratory journey to exercise pressure on the EU. Europe is not blameless in this. Transit occurs because linear migration is impossible. Absence of legal pathways of entry force migrants including asylum seekers to undertake more complex routes, often stranded for weeks, months or years in transit countries in the effort to reach their destination. In parallel, the EU has strengthened the negotiating position of transit countries, by continuing to outsource migration management, offering financial assistance in exchange for the containment of migrants. While there, as Turkey recently demonstrated, they can be used as bargaining chips or simply put, Europe can be manipulated. It is hard to project normative power to third countries when members of the Union raise walls and fences, suspend asylum processing and squabble about relocation and redistribution. The more divided internally, the projection to third countries, like Turkey, is one of weakness. It is a vicious circle that can only be broken by the EU and its member states.

Impact of COVID- 19

The crisis in Evros was soon followed by another crisis, this time a global one. As COVID-19 is wreaking havoc in the industrialised world, the migration issue has been side-lined though the reality in the hotspots remains with 42,000 asylum seekers trapped on the five Greek islands.

“While the government responded early on to the pandemic with social distancing and ‘stay at home’ orders, it is impossible to imagine how these translate in the hotspots. Social distancing is simply not an option nor is access to hygienic condition.”

While the government responded early on to the pandemic with social distancing and ‘stay at home’ orders, it is impossible to imagine how these translate in the hotspots. Social distancing is simply not an option nor is access to hygienic condition. In some parts of the Moria camp, according to the MSF, there is just one water tap for every 1,300 people and no soap available[5]. The LIBE Committee in the European Parliament called for the immediate evacuation of those most vulnerable from the hotspots, arguing it is the EU’s responsibility to assist Greece in this crisis. It is also Greece’s responsibility to ensure that the migrants are protected.

Decongestion has been slow due to the outbreak. Calling out for their evacuation during a pandemic perhaps makes even less sense than before. On the other hand, an outbreak would likely be impossible to contain, impacting both locals and asylum seekers.

Two positive steps have taken place so far.

2,000 vulnerable persons will be transferred in the coming days and weeks from the islands temporarily to the mainland with the assistance of international organisations. In parallel Greece will relocate 1,600 unaccompanied minors from the hotspots to ten (10) EU member states. Relocation is a humane, concrete demonstration of European solidarity. The process has begun and will likely conclude by end of April 2020. It will hopefully lay the groundwork for more relocation programs in the future, as more than 5,000 children remain stranded in Greece in need of long-term solutions. The new extension of the circulation ban in the hotspots and facilities around the country for COVID-19 exacerbates an already problematic situation. Though a temporary solution, it does not address the core problem that is the absence of durable solutions for those that remain in the country and the need for decent living conditions.

The way forward

In 2019 UNHCR announced that there were 25.9 million refugees. The increase is largely a result of the Syrian civil war, the continuous instability in Afghanistan, climate driven migration and extreme poverty. Unlike common belief, more than 80 per cent of all refugees are hosted in developing countries like Kenya, Pakistan, Iran, Turkey, Jordan, and Lebanon. A noticeable increase is also taking place on global displacement. 41.3 million are internally displaced by conflict, famine, and environmental degradation. Europe is hosting currently 4.391 million (UNHCR, 2019), including intra-regional refugees mainly originating from the Balkan region; a small share of a much larger population that receives protection beyond Europe.

While the socio-economic consequences of COVID-19 remain to be seen, projections are not positive. Most developing countries do not have the option of providing for social safety nets for their citizens. UNDP (2020)[6] has already warned that income losses are expected to exceed $220 billion in developing countries. Remittances will likely decrease from migrants in the developed world and the losses will impact food security, health care but also human rights. This will likely result in new migratory flows within and across regions.

“The EU should continue supporting Turkey in its efforts to host more than 3.5 million Syrian refugees. This should be the core of any new deal struck between the EU and Turkey, a reconfiguration of the Facility for Syrians to boost integration programs on the ground.”

It is unlikely that a repetition of 2015 will take place in the near future but at the same time the EU remains one of the few regions of the world where people can seek protection but also a better quality of life. It is also a region increasingly dependent on problematic neighbours (e.g. Turkey). The EU should continue supporting Turkey in its efforts to host more than 3.5 million Syrian refugees. It should continue to provide assistance in improving material conditions, access to healthcare and job market for the refugees and it should also facilitate Turkey in moving towards the integration of Syrians, since many desire to remain in Turkey.

The country is already undergoing an economic recession with mounting political problems and growing public discontent against Syrian refugees. Access to the labour market remains limited, as is schooling for many children and the Turkish incursion in Northern Syria is not necessarily an opportunity for the resettlement of the Syrians since the numbers in Turkey surpass the potential for return. Integration is key to ensuring onward migration reduces. Significant financial assistance and strong monitoring mechanisms are needed. This should be the core of any new deal struck between the EU and Turkey, a reconfiguration of the Facility for Syrians to boost integration programs on the ground, focusing predominantly on urban centers where the majority of Syrians live. A new framework is needed for EU- Turkey cooperation, promoting a model of migration governance based on protection of rights, inclusion and ultimately settlement of Syrians in Turkey. It should ideally be decoupled from returns, and the return framework – from the hotspots to physical returns to Turkey- should be redesigned.

The hotspot system, as currently implemented, is clearly not successful. Greece, despite the immense financial assistance it received, has fallen short of providing the material conditions needed for a humane stay of the asylum seekers on the islands. This has partly to do with numbers and partly with the notion that if the conditions improve people will continue to arrive. The EU bears responsibility for the outcome, as it placed enormous pressure on Greece with little support beyond financial assistance. The hotspots should return to their original form, as registration and screening centers, with people staying no more than a few days. Transfers should take place in the mainland and the EU should reach an agreement with Turkey that those eligible for returns can be transferred via flights departing from major airports. The EU should boost its monitoring mechanism in Greece to ensure that while in the mainland, asylum seekers do have their claim properly processed and their reception conditions meet the standards of the CEAS. It should strengthen the presence of the Fundamental Rights Agency in the facilities and of independent monitors through the Greek Ombundsman.

“FRONTEX coordinated return flights have not been cost-effective to date”

The way returns take place should also be reconsidered. FRONTEX coordinated return flights have not been cost-effective to date. According to the European Court of Auditors’ Special Report No 24/2019, Frontex organised 345 charter flights for Member States in 2018. There were 23,672 empty seats on those flights, an unused capacity of 43%. Return via charter flights cost Frontex EUR 2,857 per returnee. For those who do not oppose a return order, it might be worth considering returns via scheduled flights. It is also time to consider incentives to facilitate returns.

Boosting the IOM’s voluntary return programs is a step in that direction. The organisation has extensive expertise in voluntary returns. Incentives can be offered, paid out by the EU budget, to returnees. A small but positive step in that direction is the temporary mechanism for the voluntary return of 5,000 migrants from the Greek islands to their countries of origin. Initially designed to last one month, it will offer the opportunity for those in the hotspots having arrived prior to January 1, 2020, to apply to voluntarily return to their country and also receive an allowance of 2,000 euros per person funded by the European Commission. The monetary compensation is critical in encouraging returns, since for many returning home means loss of remittances but also a debt accrued that cannot be paid in the home country. It is a scheme that if successful should be considered as the foundation of returns, encouraging humane deportations.

It is also imperative to redesign the asylum system. It is not realistic to continue to depend on Turkey for the management of migration. If the EU fails to deal effectively with migration in the coming years the consequences will be significant in the future. This requires partnerships of mutual benefit with countries of origin first and foremost. Returns result in reduction of remittances, crucial in the development of third countries. They also impact demographic growth and social cohesion.

The EU needs to boost investment in countries of origin, but predominanly develop circular labour schemes, bringing in workers for seasonal work through contracts that guarantee the protection of their rights, including access to healthcare and accommodation. Circular migration enables those who seek to move for economic reasons to do so for short periods of time. They contribute to the local economies but also produce remittances. A system of checks and balances can be created to ensure the system functions in a way that benefits both countries of origin and destination. The toolbox exists, already in the Global Approach to Migration but EU member states have not utilised it. The European Commission should make it a priority to do so, especially in the post-COVID-19 world where Member States will likely turn inwards.

“An EU wide humanitarian visa scheme should be reconsidered, with mobile visa units deployed in key locations in countries of origin and transit.”

Safe and legal pathways reduce smuggling (as evident in 2015 on the western balkan route), and can address needs of both asylum seekers and economic migrants. An EU wide humanitarian visa scheme should be reconsidered, with mobile visa units deployed in key locations in countries of origin and transit. Funding can be covered by the EU budget, and an annual quota established to bring in those most in need to the EU. Such proposals have circulated in the past but where rejected as difficult to implement. The technical aspects are indeed complex. However, the benefits likely outweight the cost. People will be informed in advance what to expect in their destination country. The country will have the opportunity to prepare at national and local level for the arrivals and their integration. And it sends the signal that the EU does offer alternative pathways to protection, legal and safe thereby reducing the inducement for smuggling. This is imperative in the post-COVID-19 world, since Europe will need to provide tangible assistance and incentives to third countries to collaborate on returns. Creating alternative pathways of entry for workers and asylum seekers will boost the EU’s normative standing and facilitate relations with third countries.

Greece has a crucial role in all this, as a frontline country in the migration management, but it cannot be simply Europe’s ‘shield’. As a country on the receiving end of migrants, Greece should also consider designing a holistic policy from entry to integration. This will also give Greece a voice in the international arena in the discussion and policy proposals on migration. Those already in the country should register skills, level of education and prior work experience, and a similar screening process should take place for new arrivals. While in facilities waiting for their asylum application, language courses and skills should be taught, preparing them for either return or entry to the job market. NGOs and International Organisations could assist with expertise of similar schemes taking place around the world. Integration is the only way forward for those who will remain in the country and they should be assisted as early as possible in becoming independent. This also means a mapping is needed on what sectors of the job market have needs that can be covered also by the refugees.

“Even if a new agreement is reached between the EU and Turkey, a reboot is needed in the hotspots”

Transfers to the mainland should continue. Even if a new agreement is reached between the EU and Turkey, a reboot is needed in the hotspots. Transferring the population to the mainland will allow them access to decent living conditions and will also give time to negotiate with the locals on the way forward. Islands will need new facilities built, with more capacity and better equipped to handle high numbers should this scenario unfold in the future.

Greece should consider transferring power over integration (and funding) to municipalities. The 2015 crisis showed that the local level is often more flexible and willing to adapt to changes. Cities are where migrants and asylum seekers live, and they are called to respond to the needs of all residents. They should be empowered to do so, moving to a less centralised system of reception and integration.

Migration is a challenge, but it is also an opportunity. The world will continue to be on the move in the coming years. Climate change, poverty, civil wars, and conflicts will continue and likely increase. In a globally connected world, it is impossible to close one’s borders and the strength of liberal democracies is their willingness to limit themselves from doing so, in favour of norms and values. Practices of the past do not necessarily fit for the new reality and this is the biggest challenge for Greece and the EU; a willingness to move forward by investing on migration within Europe and beyond. It will not be easy, and it will come at a high financial (and likely political) cost. The pandemic makes any long-term commitments seem impossible, however the alternative scenario, of deterrence and outsourcing is already proving insufficient. Balancing the scales is a challenge which the EU cannot afford to lose.

[1] European Commission, Next operational steps in EU-Turkey cooperation in the field of migration, COM (2016)166 final, Brussels, 16 March 2016

[2] European Commission, Next operational steps in EU-Turkey cooperation in the field of migration, COM (2016)166 final, Brussels, 16 March 2016

[3] https://int.ert.gr/k-mitsotakis-on-the-refugee-issue-immediate-priority-is-the-decongestion-of-the-islands/

[4] https://www.unhcr.org/gr/en/13170-unhcr-urges-greece-to-strengthen-safeguards-in-draft-asylum-law.html

[5] https://www.msf.org/urgent-evacuation-squalid-camps-greece-needed-over-covid-19-fears

[6] https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/news-centre/news/2020/COVID19_Crisis_in_developing_countries_threatens_devastate_economies.html