- Contemporary Turkish and World History synthesizes Turkey’s rival political traditions into a coherent anti-imperialist narrative.

- It presents the military, economic and cultural struggle for a fully independent Turkey as the driving force in the country’s 20th century history.

- In this account, both Turkey’s much-touted drone program and ambivalence toward NATO appear as the natural culmination of long-running trends.

Read here in pdf the Policy Paper by Nicholas Danforth, Non-Resident Senior Research Fellow, Turkey Programme.

Introduction

A new 12th grade textbook, Contemporary Turkish and World History, has already received its share of international opprobrium from critics of President Erdoğan.[1] One report accused the book of “justifying” 9/11 and featuring “subtle anti-democratic messaging.”[2] A follow up article warned textbooks had been “weaponized” as part of “Erdogan’s attempts to Islamize Turkish society.”[3] On Twitter, Can Okar put it more concisely: “Turkish youth being poisoned.”[4]

Rather than simply serving as crude propaganda for Erdoğan’s regime, Contemporary Turkish and World History aspires to do something more ambitious: embed Turkey’s dominant ideology in a whole new nationalist narrative.

And yet these charges, troubling as they are, do not capture what is so significant about this book. Rather than simply serving as crude propaganda for Erdoğan’s regime, Contemporary Turkish and World History aspires to do something more ambitious: embed Turkey’s dominant ideology in a whole new nationalist narrative. Taken in its entirety, the book synthesizes diverse strands of Turkish anti-imperialism to offer an all-too-coherent, which is not to say accurate, account of the last hundred years. It celebrates Atatürk and Erdoğan, a century apart, for their struggles against Western hegemony. It praises Cemal Gürsel and Necmettin Erbakan, on abutting pages, for their efforts to promote Turkish industrial independence. And it explains what the works of both John Steinbeck [Con Şıtaynbek] and 50 Cent [Fifti Sent] have to say about the shortcomings of American society.

Contemporary Turkish and World History represents a striking, sometimes unsettling, mix of Yeni Şafak-style conspiracy theory and academic anti-orientalist critique. It certainly says a lot about where Turkey is heading. But it is not some sort of Islamist manifesto. Rather, what should alarm Turkey’s Western partners is just how easily this book could be adopted for continued use in a post-Erdoğan era. Turkey has long had competing strains of anti-Western, anti-Imperialist and anti-American thought. In the foreign policy realm, Erdogan’s embrace of the Mavi Vatan doctrine showed how his right-wing religious nationalism could make common cause with the left-wing Ulusalcı variety.[5] This book represents a similar alliance in the historiographic realm, demonstrating how the 20th century can be rewritten as a consistent quest for a fully independent Turkey.

Ankara is currently being praised for sending indigenously developed drones to Ukraine and simultaneously criticized for holding up Sweden and Finland’s NATO membership. Contemporary Turkish and World History sheds light on the intellectual origins of both these policies. Having been firmly embedded in accounts of the past, they are likely to remain popular for the foreseeable future.

Contesting Western Hegemony

Amidst a varied, engaging and detailed account of the 20th century, certain themes dominate Contemporary Turkish and World History. At the center of its narrative is the struggle for global hegemony, in military, economic, technological and artistic terms. The book features candid discussions of crude power politics, but also displays an abiding concern with injustice and its consequences.

In this account, imperialism takes center stage from the beginning.

In this account, imperialism takes center stage from the beginning. Imperial competition is cited as a main cause of World War I, and also emphasized in discussions of the war’s aftermath. European expansion in the Middle East and the Soviet reconquest of Central Asia emerge as major consequences of the war. Versailles, students learn, divided the Ottoman empire, while the Turks who had turned to the Soviet Union in the hopes of achieving self-determination found themselves facing even greater oppression. (20, 25) In this context, there is a brief flashback to Shamil’s 19th century resistance struggle in the Caucuses and an account of Enver Pasha’s guerilla campaign against the Soviets. (29, 25-27)

To frame the postwar order, the book introduces the theories of Alfred Thayer Mahan, Halford J. Mackinder, and Harry A. Sachaklian, who proposed that “the key to world domination” was control of the seas, the land and the air respectively. (37-39) The authors go on to explain that the desire for sea and air superiority drove America’s global basing policies after World War II, while Sachaklian’s emphasis on air power was vindicated by conflicts like the Vietnam War and the invasion of Iraq.

Japan’s modernization process also wins praise. The Meiji restoration is featured as “one of the most noteworthy periods in world history” during which Japan “quickly realized the technological, economic and social developments that took centuries to achieve in the West.” (40-41) Students are then asked to conduct their own research on why the Ottoman Empire’s similar reform efforts were not as successful.

Among the 1930s cultural and intellectual figures given place of pride are Albert Einstein, Pablo Picasso and John Steinbeck. Guernica is reproduced in an inset about Picasso, illustrating the artist’s hatred of war. (47) A lengthy excerpt from the Grapes of Wrath concludes with Steinbeck’s denunciation of depression-era America: “And money that might have gone to wages went for gas, for guns, for agents and spies, for blacklists, for drilling. On the highways the people moved like ants and searched for work, for food. And the anger began to ferment.” (48)

Alongside discussions of airpower, interwar architecture, and the propaganda power of the radio, this leads into the book’s explanation of World War Two. “The complex and far from just conditions created by the First World War… became the cause of the Second World War. The political, economic and social conditions in which countries found themselves were also among its reasons.” (65-66) The book places added emphasis on the harsh terms imposed on Germany at Versailles. Prefiguring the later treatment of Al Qaeda terrorism, the intention appears not so much to justify Nazism, but rather to present injustice as the causal force behind violence and cruelty in world politics.

Yet rather than being singled out, like in U.S. textbooks, as a singularly monstrous crime, the Holocaust instead appears here as one among several examples of Western barbarity.

Where previous Turkish textbooks have been criticized for neglecting the Holocaust, Contemporary Turkish and World History devotes considerable attention to it. Yet rather than being singled out, like in U.S. textbooks, as a singularly monstrous crime, the Holocaust instead appears here as one among several examples of Western barbarity. (72-74) An implicit parallel is drawn with Stalin’s deportation of Crimean Tatars and, more loosely, with the U.S. use of atomic weapons against Japanese civilians. In a discussion question at the end of the unit, students are given a graphic description of the Hiroshima explosion paired with a triumphalist quote from President Truman. They are then prompted to: “evaluate this statement from the perspective of human rights and universal values.” (101)

In explaining the establishment of the post-World War II global order, the book again returns to the theme of injustice. After a conventional account of the origins of NATO and the Cold War, the UN is introduced, alongside its subsequent failure to intervene in cases like Bosnia and Somalia. (79-80) This provides the occasion for one of Erdoğan’s only appearances in the course of three hundred pages. The book features a picture of Turkey’s president in front of a world map and the flags of the five permanent security council members. The text reads “The [UN’s] unjust internal structure and inadequacies in the face of global crises are captured in Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s slogan ‘the world is bigger than five.’”

The foundation of the UN is immediately followed by a discussion of Israel under the heading “Imperial Powers in the Remaking of the Middle East.” (80-81) The Palestine problem, students learn, is the principal cause of conflict in the region. It began when the Ottoman Empire, “the biggest obstacle to the foundation of a Jewish state,” grew weak, leading to the creation of Israel. An accompanying insert defines Zionism as “the ideal of gathering all the world’s Jews together in Palestine and rebuilding Solomon’s temple.”

Next comes a discussion of the post-war financial order and the International Monetary Fund. Students learn that “the IMF’s standard formula, which recommends austerity policies for countries in economic crises, generally results in failure, chaos and social unrest.” (81-83) An excerpt, which students are then asked to discuss, explains how the IMF prescribes different policies for developed and developing countries.

In addressing the broader global impact of World War II, Contemporary Turkish and World History gives roughly equal space to developments in military technology and in the arts. Several pages on tanks, aircraft carriers and jet fighters lead into a discussion of film, literature and architecture. (86-87) Here too, cultural politics are framed in the context of global competition, with an emphasis on the end of Western artistic hegemony. “Despite the resources at its disposal, Hollywood cinema experienced an artistic decline,” in part because of anti-communist purges in the industry. South America and the Far East did not remain content to participate in American cultural trends, but also “offered their own contributions” thanks to the efforts of directors like Keisuke Kinoshita and Akira Kurosawa. Even the numerical superiority that Hollywood had long enjoyed in film production shifted to Japan, India and China.

Ironically, only in the context of the Cold War origins of the EU does the book engage in any explicitly religious clash-of-civilizations style rhetoric. The idea of European unity is traced back to the Crusades, while a quote about the centrality of Christianity to European identity appears under a dramatic picture of Pope Francis standing with European leaders. (112) The next page states that the EU’s treatment of Turkey’s candidacy, coupled with the fact that “all the countries within it were Christian” had “raised questions” about the EU’s identity. (113)

Early Cold War era decolonization also provides an opportunity to celebrate Atatürk’s role as an anti-imperialist hero for Muslims and the entire Third World.

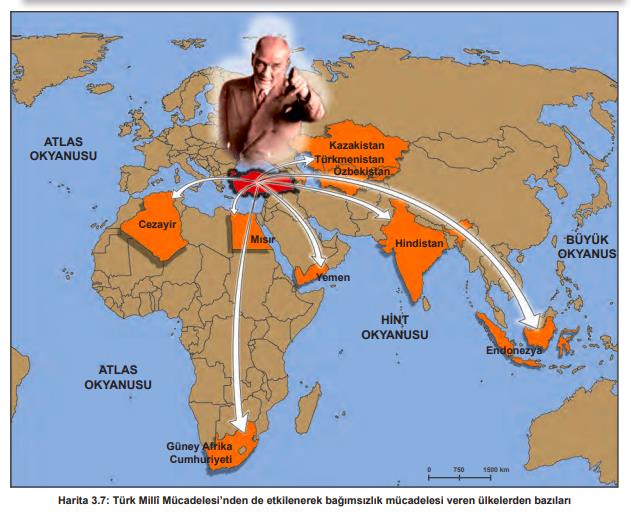

Early Cold War era decolonization also provides an opportunity to celebrate Atatürk’s role as an anti-imperialist hero for Muslims and the entire Third World. (122-123) “Turkey’s national struggle against imperialism in Anatolia struck the first great blow against imperialism in the 20th century,” the authors write. “Mustafa Kemal, with his role in the War of Independence and his political, economic, social and cultural revolutions after it, served as an example for underdeveloped and colonized nations.” Atatürk himself is quoted as saying, in 1922, that “what we are defending is the cause of all Eastern nations, of all oppressed nations.” Thus, the book explains that “the success of the national struggle brought joy to the entire colonized Islamic world, and served as a source of inspiration to members of other faiths.” The section ends with quotes from leaders such as Jawaharlal Nehru, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, and Habib Bourguiba about how Atatürk inspired them in their own anti-imperial struggles or was simply, in Nehru’s words, “my hero.” An accompanying graphic shows Atatürk’s image superimposed over a map with arrows pointing to all the countries, from Algeria to Indonesia, whose revolutions were supposedly influenced by Turkey’s War of Independence.

The Struggle for Turkish Sovereignty

Contemporary Turkish and World History has considerably more of the Cold War to cover. There is the murder of Patrice Lumumba and Simone de Beauvoir’s call for women’s rights, not to mention urbanization and Elvis. But from this point on, the book turns more directly to Turkish politics. Here, the country’s struggles against imperialism, and specifically for technological and economic independence, take more concrete form.

Amidst the polarization of the Erdoğan era, what is striking in this book is the authors’ efforts to weave together the conflicting strands of Turkish political history into a coherent narrative.

Amidst the polarization of the Erdoğan era, what is striking in this book is the authors’ efforts to weave together the conflicting strands of Turkish political history into a coherent narrative. Illustrating Ernst Renan’s argument about the role of forgetting in nation-building, this account glosses over the depth of the divisions and hostility between rival historical actors, presenting them as all working side by side toward a common national goal.[6] While Turkey’s political factions have long shared an anti-American worldview, this has more often served to divide than unite them. For decades now, both Erdogan and his opponents have accused one another of being American (not to mention Zionist) puppets working to weaken the country on behalf of its enemies. Contemporary Turkish and World History shows how this rhetoric can also have a unifying function, subsuming key political differences in the narrative of shared struggle.

İnönü wins praise for his skillful diplomatic efforts to maintain Turkish neutrality during World War II.

Perhaps the most dramatic example of this is the book’s largely positive treatment of İsmet İnönü, a man whom Erdoğan himself has sharply criticized. İnönü wins praise for his skillful diplomatic efforts to maintain Turkish neutrality during World War II. (88-92) Describing the pressure placed on Ankara by both the Allies and the Axis, the authors write that despite this, the government “followed a policy of defending Turkey’s independence and territorial integrity by staying out of the war no matter the price.” While explaining the material deprivation that Turkey suffered during the war years, the book gives İnönü himself the final word: “After the war, a man accused İnönü of leaving the nation to drink tea sweetened with raisins instead of sugar. Inonu replied, ‘but at least I didn’t leave your children orphaned.’” (101)

The authors also offer a balanced treatment of the fraught domestic politics during the period from 1945 to 1960 when Turkey held its first democratic election and experienced its first coup. (138-142, 144-146) They focus their criticism on the negative impact of U.S. aid, arguing that Washington intentionally sought to make Turkey economically and politically dependent, then sponsored a coup when these efforts were threatened. Students learn, for example, that while the United States gave Turkey military equipment, its upkeep imposed a serious burden on the country’s finances. And this, in turn, created a dependence that influenced Turkey’s foreign policy, including its decision to recognize Israel.

The book goes on to discuss the efforts of Necmettin Erbakan, as a young engineer, to break Turkey’s technological dependence on the West by creating the Gümüş Motor Factory. (143) His ambitions, the authors conclude, caused discomfort among those who wanted Turkey to remain an agricultural country. Building on this, an inset entitled “The United States and May 27” quotes Baskin Oran explaining that Washington backed the 1960 coup because it was afraid of Menderes’s efforts to industrialize Turkey.[7] (146)

Then, without missing a beat, the book continues with a section praising the new military junta’s efforts to build a domestic automobile industry. Cemal Gürsel, described simply as having “become President after the Democrat Party government came to an end with the May 27 military coup,” appears, like Erbakan, as a man committed to reversing the stifling dependence imposed on Turkey by U.S. aid. Gürsel’s automobile, the Devrim, failed dramatically in its first test and was subsequently abandoned. Yet the section ends in a triumphant note, describing the Ministry of Industry and Technology’s contemporary program to build an automobile with entirely locally parts and technology. The results, it claims, are expected to be on the roads in the early 2020s. (146-149)

Alongside the automotive industry, the book places great emphasis on Turkey’s campaign to develop domestic aircraft production. (96-98) Several pages detail the work of Nuri Demirağ and Vecihi Hürkuş during the 1930s. Hürkuş is shown as struggling against the constraints of an unsupportive bureaucracy, and quoted as saying that “Turkish youth who are not bound to the Republic, the motherland, the nation, their culture and their enduring values will have difficulty confronting the enemy in the skies.”[8] This theme is echoed in the conclusion of the book, which features a lengthy description of the satellites, drones and other aircraft (including a test plane called the Hürkuş) developed by the Turkish aerospace industry. (278-280)

The narrative of national independence also helps smooth over Turkey’s Cold War domestic divides.

The narrative of national independence also helps smooth over Turkey’s Cold War domestic divides. Students are introduced to the ‘68 Generation and left-wing leaders likes Deniz Gezmiş as anti-imperialists protesting against the U.S. Sixth Fleet in support of a fully independent Turkey. (185-186)[9] In this context, Baskin Oran’s work is again cited, this time quoting Uğur Mumcu on the role of “dark forces,” presumably the CIA, in laying the groundwork for Turkey’s 1971 coup. (203)

The book also offers a relatively neutral treatment of political activism during the ensuing decade, suggesting that rival ideological movements were all good faith responses to the country’s challenges. On this, the authors quote Kemal Karpat: “Both right and left wing ideologies sought to develop an explanation for social phenomena and a perspective on the future. A person’s choice of one of these ideologies was generally the result of chance or circumstance.” (202) Thus the authors imply that while foreign powers provoked or exploited these movements, the individual citizens who participated in them can be given the benefit of the doubt. Interestingly, the book takes a similar approach in discussing the 2013 Gezi protests: “If various financial interests and foreign intelligence agencies had a role in the Gezi Park events, a majority of the activists were unaware of it and joined these protests of their own will.” (270-271)

The Struggle Continues

Western powers remain the primary source of conflict, both within Turkey and its region. Turkey, in turn, continues to struggle against these hostile forces to strengthen its democratic stability and military power, with the ultimate aim of building a more peaceful world.

As it approaches the present, Contemporary Turkish and World History brings together the lessons of the 20th century in a way that will be familiar to followers of mainstream Turkish political discourse. Western powers remain the primary source of conflict, both within Turkey and its region. Turkey, in turn, continues to struggle against these hostile forces to strengthen its democratic stability and military power, with the ultimate aim of building a more peaceful world.

Historically and geopolitically, Turkey has a very important place in the world. Because of its geographic location, its above and below ground resources, its demography, its role as a bridge between East and West, and its democratic values, Turkey is one of the most powerful states in its region… World powers who want to weaken Turkey’s unity and the potential and the wealth it possesses are working to use ethnic, ideological and sectarian differences as a divisive element. (269)

Turkey’s foreign policy over the past two decades is presented in almost exclusively structural terms as a response to these dynamics. The book praises Ankara’s “zero problems with neighbors policy,” but makes no reference to Ahmet Davutoglu, or even the AKP’s role in implementing it. The authors write that this policy “rested on the idea that, as a regional power, Turkey should be an influential actor in multiple regions.” (257) As an example, they cite Turkey’s approach to the Balkans in the 2000s, “which aimed to secure peace and stability while limiting the regional influence of great powers.” A decade later, in Syria, “the EU prioritized its own interests over universal values,” while Turkey spent billions of dollars to aid refugees. (262)

This is the context in which the authors introduce the 9/11 attacks as a response to America’s global arrogance:

With the self-confidence it acquired after the Cold War, the United States came to see itself as holding a position of unequalled superiority in international affairs. It began giving more orders and paying less heed to international agreements. Its references and definitions determined which countries would be punished and which systems would be changed. These practices were among the reasons behind the Al Qaeda terror organization’s 9/11 attacks. (262)

The book takes a more ambivalent approach to the global impact of American culture in the 1990s. Hip hop, along with graffiti and break dancing, are “tools of social resistance” that emerged in America’s ghettos in response of the economic deprivation of the Reagan years. Students learn the name of prominent rap artists, as well as 90s pop stars (245) A section on video games is illustrated with a photo of two bored looking pre-teens, and asks whether children accustomed to solving digital problems with the press of a button will be able to solve the problems they face in real life. (246) A subsequent graphic touts the Yeşilay [Green Crescent] campaign to fight internet addiction: “log on, but don’t become dependent.” (249)

As the book’s conclusion makes clear though, Turkey’s real struggle in the 21st century, as in the 20th, is against dependence on foreign technology:

Turkey experienced the February 28 postmodern coup and two FETÖ coup attempts on 17-25 December 2013 and 15 July, 2016… In response to the foreign and domestic threats it faced in these years, Turkey intensified projects intended to decrease its foreign technological dependency. (264)

To drive the point home, the book closes with biographies of prominent Turkish scientists like Nobel Prize winning chemist Aziz Sancar. Then come the pictures of domestically produced aircraft. (275-280) Indeed, given the popularity of Turkey’s drone program in the country’s foreign policy discourse, it is striking that a book which begins with a portrait of Atatürk ends with a photo of the Bayraktar TB2.

Conclusion

In summarizing Contemporary Turkish and World History, this paper inevitably focuses on the controversial, provocative, and alarming aspects. But for anyone accustomed to consuming Sabah columns and SETA reports, this textbook reads, despite the problematic passages, like an actual history textbook. If nothing else, the book’s biases are less in the realm of wild distortion and more reminiscent of those that plague ideologically infused nationalistic history education in all too many countries. Indeed, its exaggerated critique of European imperialism may be no more misleading than the whitewashing still found in some European textbooks.[10] At moments, Contemporary Turkish and World History is better aligned with recent left-leaning scholarship than the patriotic accounts many Americans grew up reading as well.

Today, it often seems that Turkey’s aspirations for great power status reflect the facets of 20th century American power it has condemned most vigorously.

Indeed, there is something elegantly cyclical about the interplay of history and historiography here. Throughout the 20th century, America defined itself as the world’s premier anti-imperialist power, all while gradually reproducing many of the elements that had defined previous empires.[11] Today, it often seems that Turkey’s aspirations for great power status reflect the facets of 20th century American power it has condemned most vigorously. At a time when the UN can appear increasingly irrelevant, for example, Erdoğan’s fixation with expanding the Security Council feels like an almost respectful nod to the institution’s Cold War era prestige. Similarly, in promoting Turkey’s space program or overseas basing infrastructure, the Turkish media is quick to stress the fact that these are traditional markers of international influence. A Yeni Şafak article titled “Turkey is Returning to Ottoman Territory” begins by stating that “establishing military bases in other countries is seen as a possibility reserved for great military powers.”[12] It notes that the United States currently has more overseas military bases than anyone else, and concludes by stating that many countries are now clamoring for Turkish bases of their own.

Turkey’s marriage of power projection and anti-colonial critique have been particularly visible – and effective – in Africa. Ankara has presented itself as an “emancipatory actor,” while providing humanitarian aid, establishing military bases, selling weapons across the continent.[13] In doing so, Turkish leaders have faced some of the same contradictions as previous emancipatory actors. In August 2020, for example, members of Mali’s military overthrew a president with whom Erdoğan enjoyed good relations. Ankara expressed its “sorrow” and “deep concern.”[14] Then, a month later, Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu became the first foreign official to meet with the country’s new military leaders. “Like a brother,” he “sincerely shared” his hopes for a smooth “transition process” back to democracy. When U.S. Ambassador Fletcher Warren expressed similar sentiments to Cemal Gürsel on the morning of May 28th, 1960, he was undoubtedly equally sincere.[15]

Reading Contemporary Turkish and World History, one is left to conclude that Turkey has learned the lessons of the 20th century all too well.

Reading Contemporary Turkish and World History, one is left to conclude that Turkey has learned the lessons of the 20th century all too well. In a recent interview, Selçuk Bayraktar, the architect of Turkey’s drone program, said that as a student “I was obsessed with Noam Chomsky.” [16] During the 1980s and 90s, America sold Ankara F-16 jets and Sikorsky helicopters that were used to wage a brutal counterinsurgency campaign in southeast Anatolia. No one was more critical of this than left-wing scholars like Chomsky.[17] Now, Ankara is selling Bayraktar drones to Ethiopia, where they are being used to kill civilians and destroy schools in another violent civil war.[18] Students looking for extra credit after finishing their 12th grade history reading might consider evaluating this too from the perspective of human rights and universal values.

[1] Emrullah Alemdar and Savaş Keleş, Çağdaş Türk ve Dünya Tarihi [Contemporary Turkish and World History] (Devlet Kitapları, 2019)

Available online at: http://tarih34.com/birebirbilgi/resimler/files/cagdas_turk_ve_dunya_tarihi_1_2.pdf

[2] https://www.impact-se.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Erdogan-Revolution-in-the-Turkish-CurriculumTextbooks.pdf

[3] https://www.jpost.com/diaspora/antisemitism/turkey-school-textbooks-call-jews-and-christians-infidels-661051

[4] https://twitter.com/canokar/status/1508331674978992134?s=20

[5] https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/eurasianism-in-turkey

[6] http://ucparis.fr/files/9313/6549/9943/What_is_a_Nation.pdf

[7] Classified State Department correspondence reveals that in fact U.S. officials were consistently exasperated that Menderes’s economic mismanagement was undermining Turkey’s industrialization and leaving the country dependent on U.S. loans. https://www.academia.edu/6789915/Malleable_Modernity_Rethinking_the_Role_of_Ideology_in_American_Policy_Aid_Programs_and_Propaganda_in_Fifties_Turkey

[8] In similar fashion, the 2018 film Hürkuş: Göklerdeki Kahraman dramatizes Vecihi Hürkuş’s life inside the frame story of a modern high school student aspiring to win a model airplane building competition sponsored by a Turkish defense firm.

[9] On May 6th, Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoğlu spoke at an event commemorating the 50th anniversary of Deniz Gezmiş’s death “on the road to a fully independent Turkey.” In his address, which made headlines for entirely unrelated reasons, he declared his admiration for “the voices calling for a fully independent Turkey.” https://www.istanbultimes.com.tr/guncel/imamoglu-onlarin-tam-bagimsiz-turkiye-diyen-dillerine-kurban-h52514.html

[10] It is worth nothing that this book consistently identifies Russia as a Western imperialist power, even while presenting the U.S. and Britain as worse offenders.

[11] Indeed, in the aftermath of World War Two, no one was quicker to point this out than old school British imperialists.

[12] https://www.yenisafak.com/gundem/turkiye-osmanli-topraklarina-geri-donuyor-2951575

[13] ELIAMEP Policy Paper “Turkey’s “anti-colonial” pivot to Mali: French-Turkish competition and the role of the European Union in the Sahel”, Ioannis N. Grigoriadis and Dawid A. Fusiek, 21 January 2022.

[14] https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/opinion/sedat-ergin/the-coup-in-mali-and-turkeys-stance-158348

[15] Telegram from the Embassy in Turkey to the Department of State,” Foreign Relations of the United States, Vol. X, Part 2, p. 845.

[16] https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/05/16/the-turkish-drone-that-changed-the-nature-of-warfare

[17] https://youtu.be/s1lEHGT4flE

[18] https://www.politico.eu/article/evidence-civilian-bombing-ethiopia-turkish-drone/