- Natural or human-made disasters ignore borders, enthusing a common European response to civil protection.

- The EU is incrementally assuming a more active role in the field of civil protection, especially with the recent establishment of the rescEU.

- Historically, European cooperation in the field of civil protection has been slow, because of national sovereignty concerns.

- Differentiated integration is a -suboptimal- way of extending EU competences in civil protection; it speeds up the process, but it limits the potential benefits of the envisaged economies of scale and does not address sufficiently the negative externalities of disasters.

- Operation-wise, the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) frame can provide opportunities for the development of common -interoperable- capabilities, like, for example, European fire-fighting planes and helicopters.

- Closer cooperation in the field of civil protection paves the way for closer security cooperation and allows the promotion of the EU’s soft power around the world.

You may read here in pdf the Policy Paper by Spyros Blavoukos, Senior Research Fellow of ELIAMEP; Head, Ariane Condellis Programme; Associate Professor at the Athens University of Economics and Business and Panos Politis-Lamprou, BSc, Athens University of Economics and Business.

Introduction

The still ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, the 2021 summer wildfires in Greece and elsewhere in Europe’s southern rim, as well as the cataclysmic floods in Germany and Central Europe last June with more than one thousand casualties, have once again drawn the attention of the European public to the increasing need for a more effective and robust European civil protection mechanism. Such a mechanism would enhance societal resilience in the face of major crises and complement national authorities in their efforts to overcome natural or anthropogenic catastrophes of an unprecedented magnitude and scale.

“The Union Civil Protection Mechanism constitutes the EU’s response to such calls, through the RescEU and a European pool of civil protection assets (the RescEU reserve).”

Does the EU have such a mechanism? Yes, it does. The Union Civil Protection Mechanism constitutes the EU’s response to such calls, upgraded through the rescEU and a European reserve of resources (the rescEU reserve). This pool includes a fleet of member-state-owned firefighting planes, helicopters and medical evacuation planes, as well as a stockpile of medical equipment and field hospitals that can respond to health emergencies and chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear incident.

There can be no doubt that the establishing of the Mechanism and the rescEU upgrade are significant steps forward. This is especially true considering the magnitude of the challenges they pose for the existing state-centric approach to crisis management. Their establishment also foregrounds EU security integration, while encroaching on the central nexus of state sovereignty. This explains the inevitable delays and obstacles encountered along the way, which have thus far prevented rescEU from realizing its functional and operational potential, despite its having been enthusiastically embraced by the public in numerous member-states and by EU institutions alike.

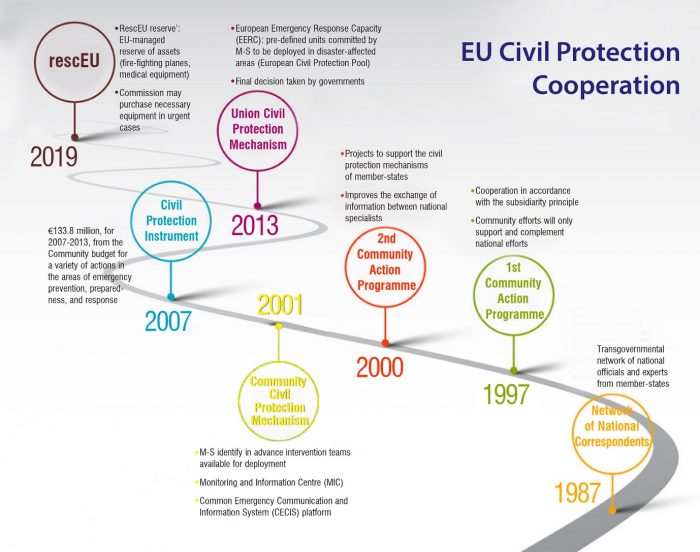

This policy paper makes a case for broadening the scope of, and further deepening the cooperation among, EU member-states in the field of civil protection. It offers an overview of the incremental steps and dynamics that have nurtured inter-state cooperation from the early efforts in the 1980s to the latest developments. It highlights the main unresolved issues and makes a set of policy proposals that could pave the way towards a real European Civil Protection Union.

The baby steps of European civil protection cooperation

“…in 1987, the Permanent Network of National Correspondents in civil protection was set up to enable better collaboration and coordination.”

In 1985, the Commission engaged with civil protection for the first time with the establishment of the Civil Protection Unit in the DG Environment. Two years later, in 1987, the Permanent Network of National Correspondents (PNNC) in civil protection was set up to enable better collaboration and coordination. It consisted of national officials and experts and sought to collect information from member-states that would allow for better assistance and its swifter activation (Official Journal of the European Communities, 1985). This was one of the first transgovernmental networks in the field of security established within the European integration framework (Hollis, 2010). Until the 1990s, several preliminary forms of strictly intergovernmental cooperation were launched, most of which focused on information and data sharing and on initiatives to enhance intra-Community cooperation in the event of a natural, human-made, or technological disaster.[1]

“…a unanimous agreement was indeed achieved in 1997, when the 98/22/EC Council Decision established a Community Action Programme in the field of civil protection.”

The cooperation honeymoon in civil protection came to an abrupt end in 1996, when the UK and the Netherlands voted against the adoption of an Action Programme in the field of Civil Protection (POLITICO, 1996). Their concern was that the EU was encroaching unnecessarily on the domestic policy-making domain and thereby violating the principle of subsidiarity. The Italian State Secretary for the Interior, who was responsible for civil protection in Italy and who represented the Council rotating Presidency, expressed the hope that a unanimous agreement on the Action Programme would be reached in the coming months (Barberi, 1996); a unanimous agreement was indeed achieved in 1997, when the 98/22/EC Council Decision established a Community Action Programme (CAP) in the field of civil protection. British and Dutch opposition was only overcome when explicit statements to the effect that the CAP would evolve in accordance with the subsidiarity principle, and only support and complement national efforts, were included in both the preamble and the operative clauses of the Decision. It was therefore evident from the start that efforts to upgrade civil protection would encounter significant political challenges, even if it was portrayed as a humanitarian-focused and apolitical process. The first CAP ran from 1998 to 1999; the second was activated in 2000 and ended in 2004. Both programmes included projects that sought to support the civil protection mechanisms of the member-states and to improve the exchange of information between national specialists (European Commission, 2002, pp. 8-9).

“In October 2001, the Community’s Civil Protection Mechanism was established.”

The second phase of increased cooperation began with the devastating earthquakes in Greece and Turkey in 1999, the terrible pollution of the Danube in 2000, and the unprecedented terrorist attacks in the USA in 2001. These natural and human-made disasters triggered further concerns about the capacity of national systems alone to handle such crises. As a result, the European Council in Ghent stressed the need for enhancing cooperation in the field of civil protection in 2001 and asked the Council and the Commission to prepare a targeted cooperation action plan. The appointment of a European coordinator for civil protection measures would be a critical stepping stone towards the achievement of closer collaboration (Commission of the European Communities, 2001, p. 2). In October 2001, the Community’s Civil Protection Mechanism was established. According to the 2001/792/EC Council Decision, member-states “shall identify in advance intervention teams” which might be available for deployment at very short notice, within 12 hours of the request for assistance being made in the event of a major emergency occurring in another member-state or in particular third countries: bilateral agreements allowed Cyprus, Malta and Turkey to participate in the Mechanism, while candidate countries in Central and Eastern Europe could also potentially access it. If civil protection assistance intervention teams were deployed outside EU territory, the member-state holding the rotating Presidency would be responsible for their coordination. Seeking to develop an effective intervention response, the Commission established a Monitoring and Information Centre (MIC) to receive the requests for assistance, and a Common Emergency Communication and Information System (CECIS) platform, which permitted member-states and the Commission to share information in real time (Fink-Hooijer, 2014, p. 138). The Commission’s supranational structures also became responsible for mobilizing teams of experts to assess the situation in the field and, along with the national authorities, to coordinate the assistance teams on site. They also launched training programmes to enhance the interoperability and coordination of the varied civil protection capacities of participating member-states.

“The frequency with which the Mechanism was activated after its establishment increased experience and generated a steep learning curve. It also highlighted the need for a major institutional and operational overhaul.”

The frequency with which the Mechanism was activated after its establishment increased experience and generated a steep learning curve. It also highlighted the need for a major institutional and operational overhaul. The deadly 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami made it clear that a still more robust civil protection mechanism was indispensable to counter the severe consequences of such extreme situations. Hence, on 7 January 2005, the extraordinary meeting of the General Affairs and External Relations Council called upon the Commission to examine possible improvements to the Mechanism and to investigate the possibility of establishing an EU Rapid Response Capability that could be deployed in crises (Presidency of the Council of the EU, 2005). At the same time, the European Parliament called for “the creation of a pool of specialized civilian civil protection units, with appropriate equipment, which should undertake joint training and be available in the event of natural, humanitarian or environmental disasters, or those associated with industrial risks, within the Union or in the rest of the world” (European Parliament, 2005, p. 5). Simply put, cooperation alone was no longer deemed enough, and the creation of a common pool of units was introduced into the debate.

“Two key elements of the report were the setting up of an operations centre to plan and prepare for emergencies, and a Civil Security Council to plan and co-ordinate efforts effectively.”

This was the spirit of the Barnier report, which was submitted to the European Union institutions in May 2006. Two key elements of the report were the setting up of an operations centre to plan and prepare for emergencies, and a Civil Security Council to plan and co-ordinate efforts effectively. Barnier’s report embraced a decentralized approach and stressed that member-states would retain control over their contributions in the form of specialised equipment and personnel until they were needed to deal with crises. However, some materials required for addressing immediate humanitarian needs – such as field hospitals, medicines, and water purification kits – could be maintained in strategic locations around the world, ready to be transported rapidly to crisis zones. According to the report, enhanced co-operation could be an option to move forward in case of objections among member-states (Barnier, 2006). The European Council endorsed the report, but its ground-breaking proposals were not taken fully on board, and no actual pooling of equipment or personnel was agreed on.

“The significant step was the creation of the Civil Protection Instrument, which provided for the sum of €133.8 million for 2007-2013, made available from the Community budget for a variety of actions in the areas of emergency prevention, preparedness, and response.”

Instead, continuity rather than change prevailed. Two new Decisions increased the European Mechanism’s readiness to deal more comprehensively with natural and anthropogenic disasters, including acts of terrorism (Farmer, 2012). Specifically, Decision 2007/779/EC included a more detailed description of the modus operandi of the Mechanism, establishing a more coherent and analytical plan of action in case of emergencies. The significant step was the creation of the Civil Protection Instrument, which provided for the sum of €133.8 million for 2007-2013, made available from the Community budget for a variety of actions in the areas of emergency prevention, preparedness, and response (Decision 2007/162/EC). Its operating framework resembles that of PESCO projects, with the Commission calling for proposals for collaborations in the domain of civil protection that could be eligible for European co-funding (Bucałowski & Kadukowski, 2013, pp. 30-31). Within this framework, Greece was one of the protagonists, since two out of the first six projects approved were led by Greek institutions and had a special focus on forest fires management (ECHO, 2014). Thus, although the qualitative step up of the Mechanism did not happen, more budgetary resources were channelled into civil protection, revealing a common will to enhance cooperation in this field, though this fell short of any breakthroughs.

The signing of the Treaty of Lisbon gave new impetus to civil protection cooperation. Firstly, the solidarity clause brought member-states closer together and encouraged further cooperation in this field. More specifically, the legal obligation to assist member-states affected by a wide range of disasters produced a new institutional and political environment conducive to fostering the pursuit of closer synergies (Villani, 2017, p. 136). Secondly, the establishment of the European External Action Service (EEAS), coupled with the ever-increasing international role of the Union, stimulated the externalisation of civil protection, with the expectation of the Union’s global footprint being strengthened (Schmertzing, 2020, p. 1).

For all the above reasons, the Commission produced two documents with substantial innovations in 2008 and 2010, respectively. The former called for a more integrated and coherent coordination, an enhanced role for the Monitoring and Information Centre that would be transformed into an EU Operations Centre, a voluntary pool of key standby civil protection modules to be deployed at any time, and increased reserve capabilities to complement and support the national authorities’ responses to major crises (Commission of the European Communities, 2008). The authors of the Commission document explicitly mentioned that the spirit of the proposals stemmed from the earlier Barnier report. The latter document reiterated most of the above-mentioned proposals, but insisted in particular on the creation of a European Emergency Response Capacity (EERC) to replace the MIC. This force would act as a voluntary pool of pre-identified civil protection assets from the participating member-states (European Commission, 2010). Once again, the national ownership of the assets and their voluntary pooling was emphasized.

“…the Commission issued an official proposal for a Decision on a Union Civil Protection Mechanism, which would be accompanied by a large increase in the budget devoted to civil protection both inside and outside the EU.”

Building on these documents, in December 2011, the Commission issued an official proposal for a Decision on a Union Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM), which would be accompanied by a large increase in the budget devoted to civil protection both inside and outside the EU. Having been notified by the member-state in which an emergency has occurred, the Commission would request the use of assets available in the voluntary pool of the EERC for emergency response operations (European Commission, 2011). Finally introduced in 2013 (Decision 1313/2013/EU), the new Mechanism expanded the scope of the EU’s action, since it could be activated in the case of any serious disaster that endangered people, the environment, or cultural heritage (Villani, 2017, p. 132). Apart from the impressive increase in the budget for the 2014-2020 period (from €133.8 million to €368.4 million), the biggest innovation was the creation of the EERC in the form of pre-defined, member-states’ owned, units committed in a European Civil Protection Pool (ECPP). This Pool would bring together resources from member-states and participating states, ready for deployment to a disaster zone at short notice, including rescue or medical teams, experts, specialised equipment, or transportation. However, despite their pre-commitment, member-states retained the right to refuse to deploy these assets (Jäkel, 2015, p. 8), which could substantially undermine the potential and responsiveness of the Mechanism.

The evolution: the rescEU reserve

“New crises called into question the sufficiency of the UCPM as a mechanism for countering the EU’s ever-increasing civil protection needs.”

New crises called into question the sufficiency of the UCPM as a mechanism for countering the EU’s ever-increasing civil protection needs. The 2014-15 migration and refugee crisis put enormous pressure on the Union, which struggled to manage the immense humanitarian impact. The lack of available assets during the 2016 and 2017 forest fire seasons also left the EU looking powerless and unable to react (European Commission, 2018, p. 2). Furthermore, there was significant demand for the EU’s humanitarian assistance services abroad, mainly in Africa, as a result of the Ebola outbreak in 2014 and the need to evacuate EU citizens from Yemen in 2015 (ECHO, 2017). The gaps in community capabilities were also outlined by the Capacity Gaps Report, published in 2017, in which particular attention was paid to limited capacity in terms of airplanes to fight forest fires and of shelter structures (European Commission, 2017, pp. 5-6). This owed much to the fact that several member-states were affected by multiple simultaneous crises, which prevented them from contributing their national assets to the common voluntary pool.

In spite, or rather because, of these challenges, European cooperation in the field of civil protection acquired greater legitimacy than ever before in the minds of the European citizenry. In the Special Barometer of May 2017, the overwhelming majority of European citizens actively supported the idea of closer cooperation. In all, 81% of the respondents believed that coordinated EU action in dealing with disasters was more effective than actions undertaken by individual countries, while 87% agreed that the Union needed a common civil protection policy; only 38% of the sample believed their country has sufficient means to deal with every major disaster on its own (European Commission, 2017, pp. 19-24). For Greece and Cyprus, the percentage was even higher, with around nine out of ten of the respondents embracing the establishment of common European civil protection capabilities.

“European cooperation in the field of civil protection acquired greater legitimacy than ever before in the minds of the European citizenry.”

Limitations in the available capabilities, coupled with the public endorsement of more cooperation in the field of civil protection, led the Commission to table a proposal in November 2017 for a new tool to reinforce the Union’s collective ability to respond to disasters immediately and adequately. The rescEU reserve constitutes a dedicated reserve of assets which, managed by the EU, could be activated when the existing capabilities at the national level, or those committed to the European Civil Protection Pool (ECPP), were either insufficient or unavailable. In an emergency, the Commission, in close collaboration with the concerned member-state or partner, decides for their deployment and mobilization (Yougova, 2019). These capabilities are still acquired by the participating member-states, but direct grants are provided to finance the procurement of additional equipment. The EU will also cover 75% of the operational costs of deploying the rescEU reserve capabilities (Morsut & Kruke, 2020, p. 6). However, it is worth noting that the Commission’s original proposal was even more ambitious, bestowing on the EU the authority to acquire its own rescEU capacities to be deployed under the Mechanism. This provision was criticized vehemently by some member-states, which believed that it transcended EU competences and that the Union was trespassing on their sovereignty (Casolari, 2019, pp. 347-348).

“RescEU tied in closely with Commission President Juncker’s agenda for “a Europe that protects”.”

RescEU tied in closely with Commission President Juncker’s agenda for “a Europe that protects”. For this reason, he endorsed the new reserve tool, stressing that “…Europe is a continent of solidarity and we must be better prepared than before, and faster in helping our Member States on the frontline” (Juncker, 2017). In the same vein, the then Commissioner for Humanitarian Aid and Crisis Management, Christos Stylianides, spoke of “an investment in disaster response” and described the rescEU reserve as “a safety net” that strengthens European solidarity (Stylianides, 2019). On behalf of the European Parliament, the rapporteur MEP Elisabetta Gardini (EPP, IT) orchestrated a massive majority of 620 MEPs to vote in favour of the rescEU. In the Council of Ministers, on 7 March 2019, only the Netherlands voted against the Decision.

“The outbreak of Covid-19 provided another push towards civil protection cooperation.”

The outbreak of Covid-19 provided another push towards civil protection cooperation. The mechanism played a major role in the management of the health crisis: due to the high demand for medical equipment and the subsequent shortages of medicines and medical devices, single member-states could not have access to vital resources (Shalal & Nebehay, 2020). To address this fundamental issue and guarantee the health of every European citizen, in 2020 the Commission took the initiative to create a strategic rescEU stockpile of medical equipment, including ventilators, reusable masks and laboratory supplies. The stockpile is hosted by one or several member-states, which can apply for a direct grant from the Union covering 90% of the stockpile’s costs (European Commission, 2020). The UCPM also helped coordinate the repatriation of European citizens, co-financing up to 75% of the transport costs. This enabled the member-states, working closely with the Emergency Response Coordination Centre (ERCC), to repatriate 90,060 EU citizens (DG ECHO, 2020).

After the first wave of the Covid-19 emergency, riding the wave of the self-evident success of the Mechanism, many members of the European Parliament— in particular those of the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety Committee, –called for more funding for the Mechanism. In September 2020, the Committee’s rapporteur, Nikos Androulakis (S&D, EL), stated that the EU should “ give the Commission the possibility to acquire, rent or lease the necessary capacities” so as to better protect and assist European citizens, no matter in which member state they reside (European Parliament, 2020). Voices of this sort were in complete agreement with the 2020 Commission’s proposal for the introduction of targeted changes to the UCPM. The Commission claimed more room for flexibility and more scope for action, noting that: “The direct procurement of rescEU capacities by the Commission would, alongside allowing autonomous action at the Union level, alleviate the financial and administrative burden on Member States”. For this reason, the Commission suggested a tenfold increase in the Mechanism’s budget, to be financed by both the Multiannual Financial Framework 2021-2027 and the EU Recovery Instrument[2] (European Commission, 2020, p. 5).

“The agreed budget was close to the initial proposal, but the Commission did not obtain the authorization and broad mandate it sought with regard to its dispersing.”

The negotiations lasted for almost a year. The Council finally agreed to the Commission’s proposals, with minor budgetary reductions, in November 2020 and the final act was signed in May 2021 (Yougova, 2021). In the European Parliament, 641 MEPs voted in favour of this act, while the Council took the decision unanimously. The agreed budget was close to the initial proposal, but the Commission did not obtain the authorization and broad mandate it sought with regard to its dispersing. As stated in Regulation 2021/836, rescEU capacities shall still “be acquired, rented, leased or otherwise contracted by Member States”, and the Commission may only purchase the necessary equipment to fill the gaps in the domain of transport and logistics. Even though the Commission may proceed with the purchase of equipment on its own, this can be done only “in duly justified cases of urgency” [emphasis added] (Murg, 2021). Nonetheless, this provision marks a new path towards a more active supranational role in the field of civil protection, since the EU is slowly acquiring the right to a common purchase of the resources needed to respond to disasters, even if only to a small extent.

The limited role of the Union acts as a safety valve for the governments of the member-states, which do not seem quite ready to give up their power in this realm. Reflecting the views of many member-states, the Finnish Minister of the Interior indicated at a press conference that, although there was widespread support for an enhanced budget for civil protection, “The primary responsibility for developing rescue capabilities and preparedness rests with the Member States, and the Commission’s actions play a supportive and complementary role” (Finnish Ministry of Interior, 2020). This statement reinstates in principle the common line of Sweden, Austria, the Netherlands, Austria and Germany as expressed in a Non-Paper issued in 2005, in which these countries reiterated the importance of the principal of subsidiarity and noted that civil protection falls within the competence of the individual state (Ekengren et al., 2007, p. 472).

Through crises, we unite…

“…through crises, the EU is moving forward in the field of civil protection.”

Is there a pattern in the incremental build-up of the European civil protection mechanism? The answer is clearly affirmative: through crises, the EU is moving forward in the field of civil protection, as in many others. The governments of member-states are realizing the added value of cooperation and are more willing to pool resources for a more effective and efficient response to natural or human-made crises and disasters. The public is also becoming more familiar with and accepting of such a prospect applying pressure on governments from below as a result. As in most security sectors, the EU depends mostly on national resources to implement its policies (Bremberg & Britz, 2009, p. 289). However, although the field of civil protection is still classified as a supporting competence (A.6 TFEU), the EU’s engagement in the field of civil protection has evolved considerably over the last two decades. This has been mainly due to the negative externalities of major disasters which have affected the broader European territory and to the limited resources member-states have available for dealing with them (Boin, Rhinard, & Ekengren, 2014). Thus, as long as crises continue to ignore borders, the EU will be under continuous pressure to adopt common actions to combat them.

“…although the reluctance of member states to cede state sovereignty to the Union would have been an insurmountable obstacle in the past, the post-pandemic period provides fertile ground for an upgrading of the EU’s civil protection policy.”

Realistically, the full transfer of civil protection competence to the Union, which would imply a centralized management of available resources by supranational institutions for the benefit of the entire European demos, is not feasible. However, although the reluctance of member states to cede state sovereignty to the Union would have been an insurmountable obstacle in the past, the post-pandemic period provides fertile ground for an upgrading of the EU’s civil protection policy (Marrone, 2020, p. 4).

Incremental steps toward the creation of a Civil Protection Union should focus at the very least on continuing and intensifying the joint purchase of equipment and medical reserves and on their management at European level. However, bolder steps can be envisaged along two axes, one institutional and the other operational. Regarding the former, since Treaty change is off the table for the foreseeable future, the provisions on enhanced cooperation (A. 20 TEU and A.326-334 TFEU) can be enacted to further the cooperation acquis in the field of civil protection. Rather than trying to adopt legally-binding provisions for all member-states, capable and willing European partners could proceed and develop joint capabilities to counter such crises. This was proposed in the Barnier report in 2006, but never took off. The advantage of such an option would be the swift operational upgrading of civil protection cooperation. Given initial successes, more member-states could be enthused to join the scheme, which is more or less what happened with security cooperation within the PESCO framework. A successful record of activities appropriately communicated to the national political communities will increase pressure from below, but also highlight the relevance and usefulness of deeper cooperation in this field. This has been the case in Sweden, for example, following the support the country received from the Mechanism in 2017, which substantially changed the country’s attitude toward more centralized cooperation in the realm of civil protection. Thus, an enhanced cooperation scheme could ignite the spark of integration.

“…an enhanced cooperation scheme could ignite the spark of integration.”

On the other hand, it is clear that such an option constitutes a sub-optimal solution, which does not take full advantage of the possible economies of scale in procuring common equipment and does not adequately mitigate the negative externalities of cross-border disasters. Furthermore, an enhanced cooperation scheme could also possibly undermine the cognitive framing of the Civil Protection Union as an initiative for the whole European demos rather than just part of it. Furthermore, operational issues relating to the deployment of these joint capabilities could arise, given the porosity of borders in the case of natural disasters. Would the participating member-states agree to share these capabilities with the rest of the Mechanism, should such a need arise? What would the response be if the Treaty’s solidarity clause was invoked?

A corollary of the enhanced cooperation rationale with an operational twist would be using the PESCO mechanism to foster closer operational cooperation among member-states willing to move beyond the existing status quo. Many PESCO projects have a civil protection dimension: the European Medical Command, the Geo-Meteorological and Oceanographic (GEOMETOC) Support Coordination Element (GMSCE), and the EU Radio Navigation Solution (EURAS), for example. Financial support for these projects through the European Defence Fund (EDF) would therefore kill two birds with one stone: in addition to the originally envisaged enhancement of security cooperation, it would also entail greater interoperability between systems necessary for civil protection. More ambitiously, new projects such as a next generation of European firefighting planes, could knock on the European Defence Agency’s door and claim EDF funding.

Is it time for a good brandy?

In Monnet’s words: “I can wait a long time for the right moment. In Cognac, they are good at waiting. It is the only way to make good brandy” (Monnet, 1976, p. 44). Monnet’s origins taught him patience and prudence as well as the realization that crises constitute opportunities (Duchêne, 1994, p. 23). “[T]he essential [thing] is to be prepared. […] If the time comes, everything becomes simple because necessity does not let us hesitate” (Monnet, 1976, pp. 38-39).

“The RescEU common reserve is currently limited in scope, and there is no sign of an EU-purchased and EU-owned pool of resources on the horizon.”

Is the wait for an all-encompassing Civil Protection Union coming to an end? Don’t hold your breath! As in the discussion on security and defence integration, capabilities show the way. Without them, discussions only raise expectations that can lead to disappointments. The rescEU common reserve is currently limited in scope, and there is no sign of an EU-purchased and EU-owned pool of resources on the horizon.

“Without suggesting that the EU should capitalize on human pain and destruction, enhancing civil protection cooperation would constitute a valuable asset to a ‘global Europe’ and the geopolitical aspirations of the EU.”

Still, there are three good reasons why we should consider the glass half-full and look forward to its being filled still further:

- Strengthening cooperation in the field of civil protection entails irrefutable economies of scale in the procurement and production of equipment necessary for dealing with crises. The taking on board of this point has already led to the planned purchase in a single order of a large number of firefighting aircraft by several EU member-states, as a way to bring back to life the Canadair production line discontinued in 2015 (Granié, 2021; Le Sénat, 2021). It has become even more evident in the years of the pandemic and the coordinated efforts made to address the logistical challenge of combatting Covid-19. More ambitiously, closer cooperation could even lead to the production of necessary capabilities. PESCO and the EDF mechanism can provide a framework for the joint development of fire-fighting planes and helicopters, following the example of the European Patrol Corvette.

- Society has embraced a Civil Protection Union and puts continuous pressure on the governments of member-states. Unfortunately, both natural and human-made catastrophes will continue, but their negative impact will amplify voices in the European and national demoi that are calling for a more integrated European civil protection policy.

- Efforts to establish a Civil Protection Union could ride the wave of security and foreign policy integration, and actually promote both via the back door. The interconnection between civil protection and security is more apparent than ever in today’s world. In 2019, the otherwise sceptical Finland, which held the Presidency of the Council at the time, proposed reinforcing the Mechanism’s capacity to deal with increasingly complex and hybrid threats and risks including “chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear threats” (Finnish Ministry of the Interior, 2019). Furthermore, the civil protection mechanism is not confined to within the borders of the EU. In 2020 alone, it was activated after the explosion in Beirut, the floods in Ukraine, Niger and Sudan, and the tropical cyclones in Latin America and Asia (DG ECHO, 2021), therefore contributing substantially to, and projects, the EU’s soft power around the world. Without suggesting that the EU should capitalize on human pain and destruction, enhancing civil protection cooperation would constitute a valuable asset to a ‘global Europe’ and the geopolitical aspirations of the EU.

[1] Examples of such actions can be found in the resolution of 13 February 1989 on the new developments in Community cooperation on civil protection, the resolution of 23 November 1990 on Community cooperation on civil protection, the resolution of 23 November 1990 on improving mutual aid between Member States in the event of a natural or man-made disaster and the resolution of 8 July 1991 on improving mutual aid in the event of a natural or technological disaster.

[2] The total budget for the Union Mechanism would derive from both the Multiannual Financial Framework 2021-2027 (€1,268,282,000) and the EU Recovery Instrument (€2,187,620,000). The total financial resources would amount to €3,455,902,000.

Bibliography

Barberi, F. (1996). 1927th Meeting Of The Council – Civil Protection – Brussels, 23 May 1996 – President : Mr. Franco Barberi, State Secretary For The Interior, Responsablefor Civil Protection, Of The Italian Republic. Rome: European Commission.

Barnier, M. (2006). For a European civil protection force: europe aid.

Boin, A., Rhinard, M., & Ekengren, M. (2014). Managing Transboundary Crises: The Emergence of European Union Capacity. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, 22(3), 131-142.

Bremberg, N., & Britz, M. (2009). Uncovering the Diverging Institutional Logics of EU Civil Protection. Cooperation and Conflict: Journal of the Nordic International Studies Association, 44(3), 288-308.

Bucałowski, A., & Kadukowski, D. (2013). Civil protection in the EU and its effect on the safety of the Baltic region. Baltic Region, 3, 27-36.

Casolari, F. (2019). Europe (2018). In Yearbook of International Disaster Law (pp. 346-354). Brill | Nijhoff.

Commission of the European Communities. (2001). Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

Commission of the European Communities. (2008). Communication From The Commission To The European Parliament And The Council: on Reinforcing the Union’s Disaster Response Capacity. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

DG ECHO. (2020, 12 10). Bringing stranded citizens home. Retrieved 10 3, 2021, from European Commission / ECHO: https://ec.europa.eu/echo/field-blogs/photos/bringing-stranded-citizens-home_en

DG ECHO. (2021). EU Civil Protection Mechanism. Brussels: DG ECHO.

Duchêne, F. (1994). Jean Monnet : the first statesman of interdependence. New York: Norton.

ECHO. (2014, 7 28). Civil protection financial instrument 2007. Retrieved 9 26, 2021, from European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations: https://ec.europa.eu/echo/funding-evaluations/financing-civil-protection/civil-protection-financial-instrument-2007_en

ECHO. (2017). What is the Union Civil Protection Mechanism. Retrieved 9 27, 2021, from ECHO: https://ec.europa.eu/echo/sites/default/files/what_is_the_union_civil_protection_mechanism.pdf

EU MODEX. (2021). EU MODEX. Retrieved 11 20, 2021, from EU MODEX: https://www.eu-modex.eu/Red/

Ekengren et al. (2006). Solidarity or Sovereignty? EU Cooperation in Civil Protection. European Integration, 28(5), 457-476.

Ekengren et al. (2007). Solidarity or Sovereignty? EU Cooperation in Civil Protection. Journal of European Integration, 28(5), 457-476.

European Commission. (2002). EU Focus on civil protection. Brussels: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

European Commission. (2010). Communication From The Commission To The European Parliament And The Council: Towards a stronger European disaster response: the role of civil protection and humanitarian assistance. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2011). Proposal for a Decision of the European Parliament and of the Council on a Union Civil Protection Mechanism. Brussels: Council of the European Union.

European Commission. (2017). Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council on progress made and gaps remaining in the European Emergency Response Capacity. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2017). Special Eurobarometer 454 – Civil Protection. Brussels: Directorate‐General for European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations.

European Commission. (2018). Proposal for a Decision of the European Parliament and of the Council amending Decision No 1313/2013/EU on a Union Civil Protection Mechanism. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2018, 8 6). Record EU Civil Protection operation helps Sweden fight forest fires. Retrieved 11 20, 2021, from European Commission: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_4803

European Commission. (2020). COVID-19: Commission creates first ever rescEU stockpile of medical equipment. Brussels: European Commission.

European Commission. (2020). Proposal for a decision of the European Parliament of the Council amending Decision No 1313/2013/EU on a Union Civil Protection Mechanism. Brussels: European Commission.

European Parliament. (2005). European Parliament resolution on the recent tsunami disaster in the Indian Ocean. Brussels: European Parliament.

European Parliament. (2020, 9 3). Greater EU Civil Protection capacity needed in light of lessons from COVID-19. Retrieved 10 3, 2021, from European Parliament Press Releases: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20200903IPR86304/greater-eu-civil-protection-capacity-needed-in-light-of-lessons-from-covid-19

Farmer, A. M. (2012). Manual of European Environmental Policy. London: Routledge.

Fink-Hooijer, F. (2014). The EU’s Competence in the Field of Civil Protection (Article 196, Paragraph 1, a–c TFEU. In I. Govaere, & S. Poli, EU Management of Global Emergencies: Legal Framework for Combating Threats and Crises (pp. 137-146). Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Finnish Ministry of Interior. (2020). EU Commission proposal to amend the Union Civil Protection Mechanism for deliberation in Parliament. Helsinki : Finissh Government.

Finnish Ministry of the Interior. (2019). EU Civil Protection Mechanism must respond to increasingly complex threats. Retrieved 11 20, 2021, from Ministry of the Interior: https://intermin.fi/en/eu2019fi/programme/civil-protection-mechanism

Granié, N. (2021, 8 18). Incendies : la France confrontée au vieillissement de sa flotte aérienne. Retrieved 11 24, 2021, from Les Echos: https://www.lesechos.fr/politique-societe/societe/incendies-la-france-confrontee-au-vieillissement-de-sa-flotte-aerienne-1339535

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., & Zingales, L. (2014). ‘Monnet’s Error?’. London: LSE ‘Europe in Question’ Discussion Paper Series.

Hollis, S. (2010). The necessity of protection: Transgovernmental networks and EU security governance. Cooperation and Conflict, 45(3), 312-330.

Jäkel, G. H. (2015). The Union Civil Protection Mechanism under European and International Law. Groningen: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen.

Juncker, J.-C. (2017). RescEU: A stronger collective European response to disasters. Brussels: European Commission.

Le Sénat. (2021). Projet de loi de finances pour 2022 : Sécurités (Sécurité civile). Retrieved 11 24, 2021, from Sénat: http://www.senat.fr/rap/l21-163-329-2/l21-163-329-23.html

Marrone, A. (2020). The COVID-19 Pandemic and European Security: Between Damages and Crises. Rome: Istituto Affari Internazionali (IAI).

Monnet, J. (1976). Mémoires. Paris: Librairie Arthème Fayard.

Morsut, C., & Kruke, B. I. (2020). Europeanisation of Civil Protection: The cases of Italy and Norway. International Public Management Review, 20(1), 23-42.

Murg, R. (2021). EU Civil Protection mechanism: rescEU. Brussels: European Commission.

Official Journal of the European Communities. (1985). Resolution of the Council and the representatives of the Governments of the Member States, meeting within the Council of 25 June 1987 on the introduction of Community Cooperation on Civil Protection. Brussels: Official Journal of the European Communities.

POLITICO. (1996, 5 29). 23 May Civil Protection Council. Retrieved 9 25, 2021, from Politico: https://www.politico.eu/article/23-may-civil-protection-council/

Presidency of the Council of the EU. (2005). Earthquake and tsunami in the Indian Ocean. Brussels: Council of the EU.

Schmertzing, L. (2020). EU civil protection capabilities. Brussels: EPRS Ideas Paper.

Shalal, A., & Nebehay, S. (2020, 3 3). WHO warns of global shortage of medical equipment to fight coronavirus. Retrieved 10 3, 2021, from Reuters: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-idUKKBN20Q14O

Stylianides, C. (2019, 5 25). I say Europe, you say…? Interview with Christos Stylianides. Retrieved 9 27, 2021, from Wilfried Martens Centre for European Studies: https://www.martenscentre.eu/i-say-europe/i-say-europe-you-say-interview-with-christos-stylianides/

Szele, B. (2003). “Crises are opportunities” Jean Monnet and the first steps toward Europe. European Integration Studies Miskolc, 2(2), 5-15.

Villani, S. (2017). The EU Civil Protection Mechanism: instrument of response in the event of a disaster. Revista Universitaria Europea, 26, 121-148.

Yougova, D. (2019, 11 20). Revision of Decision 1313/2013/EU for a fully-fledged European Union Civil Protection Mechanism with own operational capacities. Retrieved 9 27, 2021, from European Parliament: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-area-of-justice-and-fundamental-rights/file-eu-civil-protection-mechanism

Yougova, D. (2019, 11 20). Revision of Decision 1313/2013/EU for a fully-fledged European Union Civil Protection Mechanism with own operational capacities. Retrieved 9 27, 2021, from European Parliament: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-area-of-justice-and-fundamental-rights/file-eu-civil-protection-mechanism

Yougova, D. (2021). Union Civil Protection Mechanism 2021-2027. Brussels: European Parliament.