In recent decades, the European Court of Human Rights has evolved into a leading judicial body which examines and identifies violations committed by states in the management of migration and asylum. Greece is one of the countries that has been condemned in a large number of judgements relating to administrative detention, reception and accommodation conditions, the treatment of migrants by the police and border authorities, the asylum system, the treatment of unaccompanied minors, and human trafficking. This paper examines the Greek authorities’ compliance with the ECtHR judgements in this area. It focuses on general measures which relate to broader changes in the legislation and case law, as well as on administrative practice in Greece. It analyses the obstacles and difficulties present in this area, and it makes policy recommendations. It argues that a new approach is needed to Greece’s compliance with regard to the human rights of migrants and refugees. This approach should be focused on structural reforms and it should have the express commitment of the country’s political leadership. It would require systematic efforts to instil a new mindset within the public administration that is supportive of human rights protection as a priority and democratic responsibility, rather than as an externally imposed, necessary evil.

Read here in pdf the Policy Paper by Dia Anagnostou, ELIAMEP Senior Research Fellow; Associate Professor of Comparative Politics at Panteion University of Social Sciences.

The research on which this paper is based was carried out within the framework of the LAWMIGRAS project “Do European states abide by human rights in migration and asylum? A study of compliance and implementation of Strasbourg Court rulings” (OPPORTUNITY/0916/MSCA/0019). The project was run at the University of Cyprus in 2020-2022 (Department of Law) and was funded by the Research and Innovation Foundation of Cyprus.

INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS LAW forms an effective framework for protection and external control, recognising individuals as possessing rights, whether they are citizens of a state or not. Contracting states must define and constrain their actions, including in the area of migration, in accordance with fundamental human rights principles. Stage policies and practices regarding the entry, stay and overall treatment of migrants, often test the limits of respect for human rights as states—even established democracies—seek to restrict migration and assert their national sovereignty.

State policies and practices regarding the entry, stay and overall treatment of migrants, often test the limits of respect for human rights as states—even established democracies—seek to restrict migration and assert their national sovereignty.

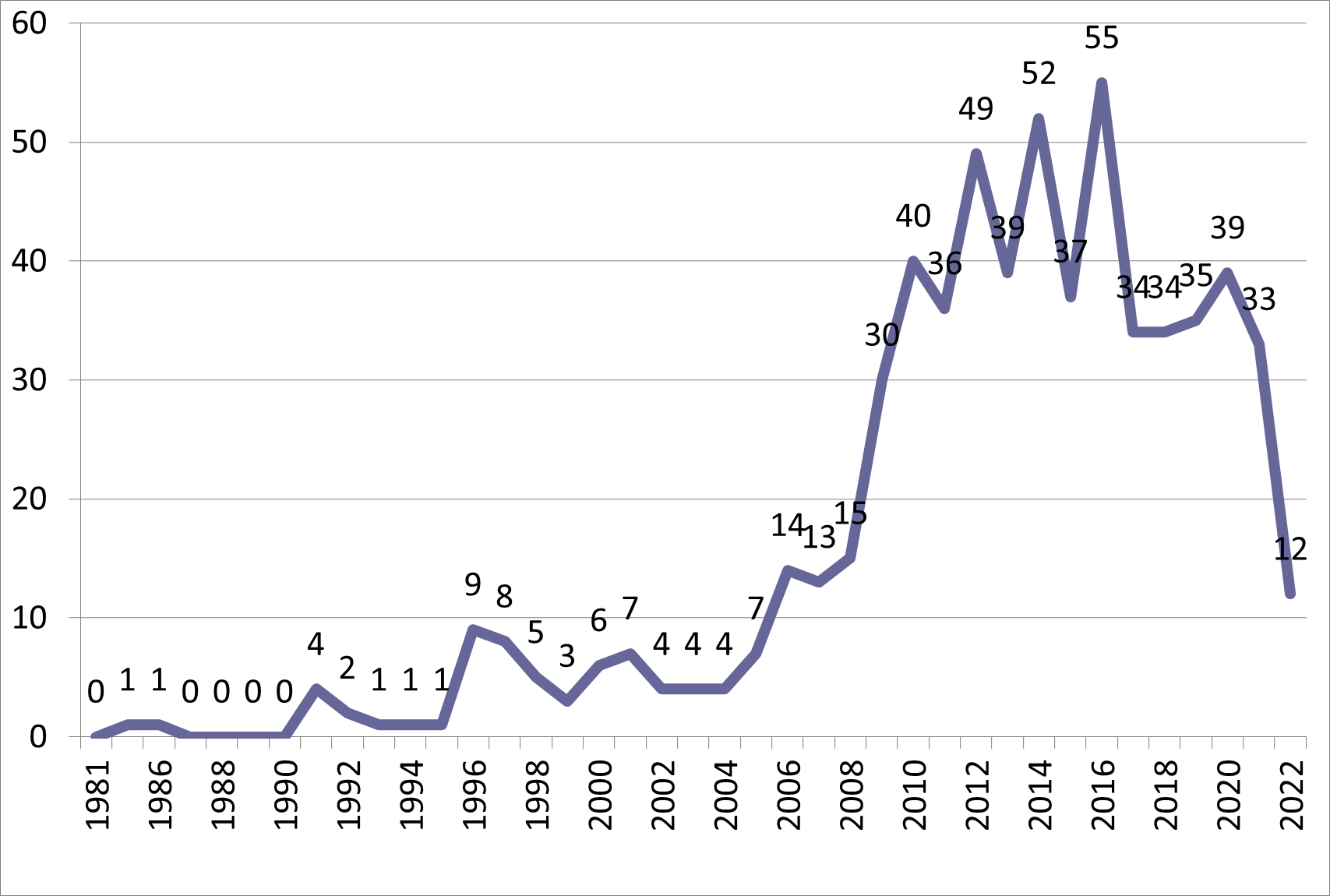

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR, or the Convention), and the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR, or the Court) which interprets and enforces it, provide an advanced mechanism for the protection of rights. The Convention contains general rights principles without referring specifically to migrants or refugees. Nonetheless, the ECtHR has evolved in recent decades into a leading judicial body which examines and identifies violations by states in the management of migration and asylum; the large increase in the relevant judgements and decisions that it has issued in recent decades attests to its growing importance in this regard (Fig. 1). In the period 1980-2020, the ECtHR delivered more than 600 judgements concerning migrants and issues relating to the management of legal and irregular migration and asylum. In 75% of these decisions, it found at least one violation of the ECHR[1].

Fig. 1: ECtHR decisions concerning migrants, 1980-2022 (Source: Author’s own data).

In dozens of relevant cases, Greece was found to be in violation of the ECHR with regard, inter alia, to administrative detention, reception and accommodation conditions, the treatment of migrants by the police and border authorities, the asylum system, the treatment of unaccompanied minors, and human trafficking.

Over the last twenty years, Greece has been one of the countries with a large number of cases and adverse judgements relating to migrants and asylum seekers[2]. In dozens of relevant cases, Greece was found to be in violation of the ECHR with regard, inter alia, to administrative detention, reception and accommodation conditions, the treatment of migrants by the police and border authorities, the asylum system, the treatment of unaccompanied minors, and human trafficking. Other countries, such as France, Britain, Belgium and the Netherlands, were also found to violate the Convention in a significant number of immigration-related judgements and decisions. The ECtHR’s expanded oversight in the field of immigration has provoked reactions from states. In countries like Britain and Denmark, their governments have on occasion questioned the degree to which the ECtHR is legitimized to exercise judicial review in an area that is considered to lie at the heart of national sovereignty.

Countries like Britain and Denmark, their governments have on occasion questioned the degree to which the ECtHR is legitimized to exercise judicial review in an area that is considered to lie at the heart of national sovereignty.

This paper examines the Greek authorities’ compliance with the relevant ECtHR judgements, focusing on general measures that have the potential to bring about substantial changes in administrative practice and public policy. It analyses the obstacles and difficulties in this area and it makes policy recommendations that could improve the compliance and responsiveness of the Greek authorities. The first section provides a brief description of the ECHR mechanism, its judicial review, and the Council of Europe supervision over state implementation of the Court’s judgements. The second section examines the gaps and shortcomings relating to the protection of migrants’ and refugees’ rights in Greece. The third and fourth sections analyse the implementation of Greek authorities with the relevant ECtHR judgements and decisions. The paper ends with policy recommendations aimed at improving Greek authorities’ compliance and the protection of migrants and refugees.

The ECHR supervisory mechanism for implementing ECtHR decisions

As an institution of the Council of Europe, the ECHR is separate from the European Union, yet it exerts considerable influence over the EU’s system of fundamental rights protection.

The European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), based in Strasbourg and established in 1959, reviews individual petitions raising claims of rights violations and issues judgements which the contracting states are obliged to implement. It is the cornerstone of the regional regime constructed in the post-war period within the Council of Europe (CoE) for the protection of human rights. Its aim was to prevent the takeover of power by authoritarian governments and the dismantling of democracy, which were key factors that had led to World War Two.[3] The Court’s jurisdiction extends to 47 CoE member states with a population of 800 million, which have incorporated the ECHR into their domestic legal orders.[4] As an institution of the CoE, the ECHR is separate from the European Union (EU), yet, it exerts considerable influence over the EU’s system of fundamental rights protection.

The ECHR for the first time made it possible for individuals to invoke international law before a European judicial body against states that violate human rights. Any individual may bring a petition claiming that state authorities have violated his or her fundamental rights, provided that he or she has previously exhausted all national remedies (the ECHR is subsidiary to national legal order). By extending to individuals the right to petition, the ECHR revolutionized the nature of international law, which was traditionally limited to disputes between states. The Convention has since served as an inspiration and a model for similar regional human rights protection systems in other parts of the world, including the Americas and Africa.

In the context of individual petitions, and in an expanded field of state action, the ECtHR examines whether actions or omissions on the part of state institutions are in violation of ECHR principles. Its review extends inter alia to the delivery of justice, conditions of detention, violence and inhuman treatment by security forces and the police, immigration, religious freedom, discrimination against and restrictions on minorities and minority views, the protection of vulnerable persons, gender-based violence, reproductive rights and the protection of property rights.

The extension of ECtHR review to such a wide range of state actions is a result of the dramatic increase of individual litigation over the last decades, which has brought a range of human rights problems to the Court’s attention. Lawyers, independent authorities and non-governmental organisations represent migrants and asylum seekers and provide them with legal support before the ECtHR. Many non-governmental organisations also provide valuable assistance to the Court (in the form of factual information, references to international comparative law, etc.) as third-party interveners in cases brought before it.

A key feature of the ECHR is the obligation it imposes on contracting states to implement ECtHR judgements.

A key feature of the ECHR is the obligation it imposes on contracting states to implement ECtHR judgements. The aim of implementation is not only to eliminate the violations for each individual (individual measures), but also to prevent their recurrence in the future (general measures). The Committee of Ministers (CM) of the Council of Europe, an intergovernmental body composed of representatives of the contracting states, oversees domestic implementation of ECtHR judgments, in cooperation with the Council of Europe’s Department for the Execution of Judgements. When the CM assesses that the national authorities have taken adequate compliance measures, it terminates its supervision by issuing a final resolution.

The CoE supervisory bodies do not require or impose specific legislative, administrative or other compliance measures on national authorities which formulate the implementing measures with wide discretion.

It is important to note that the aforementioned CoE supervisory bodies do not require or impose specific legislative, administrative or other compliance measures on national authorities. Instead, the national authorities of the respondent state formulate the implementing measures with wide discretion. They opt for measures which they believe can eradicate the rights violations identified in the ECtHR judgements or which they simply deem to be politically feasible. That states comply fully with the judgements of the Court is crucial for the effectiveness, legitimacy and overall authority of the ECtHR.

Over the last 15-20 years, the ECHR machinery for supervising judgment implementation has been radically restructured in response to a growing number of repeat violations.

Over the last 15-20 years, the ECHR machinery for supervising judgment implementation has been radically restructured in response to a growing number of repeat violations. These are in part (but not entirely) related to the ECHR’s enlargement in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, where a democratic tradition and established rule of law was lacking. The CM supervision now focuses on systemic human rights problems that stem from the structure and functioning of entire areas of state administration (rather than from occasional lapses that lead to rights violations). Furthermore, the CM’s new working rules now allow non-governmental bodies (NGOs, independent authorities, academic and research institutes, bodies of international organisations) to engage in judgment implementation.[5] They can provide the CM with reports, proposals and critical analyses of the measures proposed by the national authorities. In doing so, they provide more comprehensive documentation and greater transparency regarding the human rights situation in a given country.

The implementation of ECtHR judgements and decisions on migrants in Greece

In Greece, the implementation of ECtHR judgements is primarily the competence of the Legal Council of the State (LCS), which also represents the government in cases before the ECtHR. It communicates with the ministries who are competent to formulate the implementing measures (legislation, administrative practices, other measures) in each case, and it conveys the relevant action plans to the CM and the Department for the Execution of Judgements. National courts also have a key role to play in implementing the judgements, especially in cases where compliance requires aligning their case law with that of the ECtHR. The Special Standing Committee for the Execution of Judgments in the Greek Parliament could also assume an important role. This Committee was established with the aim of exercising parliamentary control of the public administration in this area.

The Greek Ombudsman regularly calls on the Greek administration to comply with ECtHR judgments with its competence to oversee return/readmission procedures and as a National Mechanism for the investigation of abuses of police power and for the prevention of torture.

While they do not have formal powers to enforce ECtHR judgements, independent authorities such as the Greek Ombudsman and institutions like the National Commission for Human Rights[6] have a crucial role to play in Greece’s compliance. They monitor and report on ECtHR judgments, they propose measures and draw up reports, even after the CM has terminated its oversight. For its part, the Greek Ombudsman regularly calls on the Greek administration to comply with ECtHR judgments. It invokes these judgments not least through its competence a) as a monitoring body overseeing immigrants’ return/readmission procedures and b) as a National Mechanism for the investigation of abuses of police power and for the prevention of torture.[7].

Overall, Greece has improved its implementation in terms of the number of ECtHR judgements under supervision by the CM. It is now roughly on a par with the European average in terms of time it takes to implement decisions and in terms of the percentage of the judgements, in which implementation is still pending[8]. However, formal compliance with ECtHR judgements does not necessarily go hand in hand with substantive implementation of human rights in administrative practice and government policy. Measures adopted by national authorities, such as legislation or accommodation structures, are often inadequate, or they are not (effectively) put into practice.

The legal concept of compliance is ill-suited to the nature and exigencies of ECtHR judgements in which human rights violations are of a systemic nature. These include violations which relate to the lawfulness of immigration detention and detention conditions, migrants’ treatment by the police and border authorities, the asylum system, and human trafficking. Systemic violations are not addressed through partial measures that tackle specific or isolated shortcomings of law and administrative practice, but they often require far-reaching reform of entire sectors of public administration.

A large number of the condemnatory judgements issued by the ECtHR against Greece relate to the lawfulness and conditions of administrative detention of migrants.

A large number of the condemnatory judgements issued against Greece by the ECtHR relate to the lawfulness and conditions of administrative detention of migrants[9]. In the 2000s, those judgments were instrumental in prompting the Greek authorities to adopt a legislative framework for the regulation of administrative detention (no such framework existed before 2008), which was harmonised with the procedural and substantive guarantees of ECtHR case law and EU legislation[10]. Additional legislation provided for judicial control of the conditions of administrative detention, and the possibility of migrants to take recourse to administrative courts[11]. In practice, however, many courts have continued to exercise a formal kind of control, failing to conduct a thorough examination of the conditions in which migrants are detained. The fact that there is no provision in Greece to appeal the relevant decisions of administrative courts makes it easier to exhaust the national remedies available. Following a judgement made by a court of first instance, many cases are directly taken to the ECtHR, which continues to issue condemn Greece about the conditions in which immigrants are detained[12].

Despite the improvements made in the legislative framework, the systematic detention of migrants and asylum seekers continues to be a central pillar of immigration management by successive Greek governments. The conditions of such detention continue to fall short of the minimum standards that ensure respect for human dignity. The effort to decongest the detention centres in 2015-16 was short-lived. The increase in capacity achieved through the construction of new hotspots was insufficient to meet the unprecedented increase in arrivals at the time. Adopted in 2016 in the context of the implementation of the joint EU-Turkey declaration, new legislation improved certain guarantees, but simultaneously increased both detention time and introduced geographical limitations for newly-arrived migrants in unacceptable conditions[13]. Despite numerous and repeated judgements against Greece, the CM ended its oversight of immigration detention cases on the grounds that the Greek state had now put in place an effective remedy. Nonetheless, the CM continues to monitor the problems in this area in the context of its oversight of M.S.S. v. Greece.

In the landmark judgment of M.S.S. v. Greece and Belgium, the ECtHR found a number of violations concerning the asylum system in Greece—or, more precisely, the absence of such a system until 2013[14]. Greece was condemned for its detention conditions, but also for the lack of welfare provisions for asylum seekers, who often lived in conditions of total destitution. Other condemnatory decisions highlighted the inappropriate conditions in which unaccompanied minors were detained, along with the general lack of care and protection afforded to this especially vulnerable category of migrants[15].

Following the issuing of the M.S.S. judgement in 2011, Greek authorities implemented significant legislative and structural changes – above all the establishment of a full-fledged asylum service and the expansion of first-reception facilities. […] However, ongoing shortcomings, poor implementation and the conditions created in 2015-16, led to new rights violations related to conditions in the reception and accommodation centers, despite their significantly increased capacity.

Following the issuing of the M.S.S. judgement in 2011, Greek authorities implemented significant legislative and structural changes – above all the establishment of a full-fledged asylum service and the expansion of first-reception facilities[16]. The M.S.S. judgment was not the only factor that led Greek authorities to set up an asylum system that meets basic standards and guarantees; the European Union had been pressuring Greece for this for years to implement such a system. However, the M.S.S. ruling served as a catalyst, and created the framework for sustained European supervision (in January 2023, the M.S.S. case remained open, under the supervision of the CM). In the past decade, several non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and non-state actors have made interventions on the implementation of the M.S.S. before the CM. During this time, the conditions relating to immigration in Greece have radically changed. Non-governmental actors’ interventions critically analysed the measures taken by the Greek authorities, provided useful factual information, and formulated proposals for improvement.

The creation of the Asylum Service and first-reception structures—a complex and costly undertaking launched in a period of deep fiscal and political crisis—improved access to an asylum process in a period when migrant inflows sharply rose. However, ongoing shortcomings, poor implementation and the conditions created in 2015-16, including due to the EU-Turkey statement in March 2016, led to new rights violations related to conditions in the reception and accommodation centres, despite their significantly increased capacity. The M.S.S. ruling had a further impact (for Greece), namely, the freezing of asylum returns to Greece by other EU Member States in the context of the Dublin Regulation. This came at a price, of course: the discrediting of Greece internationally due to the seriousness of its rights violations.[17]

Early in 2022, the Hellenic Ministry of Migration and Asylum published its National Strategy for the Protection of Unaccompanied Minors, the implementation of which is still in its early stages.

Concerning the provision of state care for unaccompanied minors, Greece introduced a system of guardianship several years after the ECtHR issued its condemnatory judgement in Rahimi (Law 4554/2018, Articles 13-32). The CM of the Council of Europe assessed it positively and urged the Greek government to implement it and to provide appropriate accommodation facilities. In 2019-2020, the CM urged the Greek authorities to step up their efforts to improve accommodation conditions, along with access of migrants and asylum seekers to health services and education[18]. Early in 2022, the Hellenic Ministry of Migration and Asylum published its National Strategy for the Protection of Unaccompanied Minors, the implementation of which is still in its early stages.

More than ten adverse judgements by the ECtHR over the last decade have highlighted the serious problem of violence and ill-treatment perpetrated by police and border authorities, often with migrants as victims. Many of the relevant judgements were under the CM supervision in the Makaratzis v Greece group of cases[19]. A primary cause of Greece’s ECHR violations was its failure to effectively investigate such incidents and impose severe penalties on those involved. The response of the Greek authorities in those cases was protracted, remaining minimal to non-existent for many years[20].

Positive changes include improvements made to the disciplinary code in place within the police force, and the introduction of administrative measures for investigating racist motives in cases of police violence.

The ECtHR’s judgements in this area played a key role, first for authorities to acknowledge that ill-treatment by police forces was a serious problem. Secondly, they were catalytic for in the adoption of a supervisory mechanism designed to address this ill-treatment. In 2016, the National Mechanism for the Investigation of Incidents of Arbitrariness (Law 4443/2016) was created as a special competence of the Ombudsman, and it was strengthened further in 2020 by means of Law 4662/2020. The Ombudsman became responsible for independently investigating allegations of arbitrary conduct. It referred cases of alleged abuse to the disciplinary bodies of the police forces for investigation, including cases in which the ECtHR considers the conducted investigation incomplete or inadequate. Other positive changes include improvements made to the disciplinary code in place within the police force, and the introduction of administrative measures for investigating racist motives in cases of police violence. They also included amendment of the Criminal Code to align its definition of torture with international conventions and to define stricter penalties for racially motivated crimes.

After the Prime Minister apologized in the Hellenic Parliament in March 2021 for abuse and violence perpetrated by the Greek police, the CM of the Council of Europe decided to terminate its supervision of the Makaratzis group of cases (13 judgements in total). However, the CM also expressed its concern about the continuing incidents of police ill-treatment, citing reports of the Council of Europe’s Committee against Torture, and referring to the incomplete and delayed investigation of incidents by the police. The CM ended its supervision of the Makaratzis v. Greece group of cases, but it continues to monitor Greece in this area (in the context of the Sidiropoulos and Papakostas group of cases) [21].

Conclusions and policy recommendations

Τhe implementation of the ECtHR judgements and the protection of human rights in general apparently have not been a priority for any Greek government.

Following this brief overview, we can draw the following conclusions: Firstly, the implementation of the ECtHR judgements and the protection of human rights in general apparently have not been a priority for any Greek government. This lack of interest is even more pronounced in the case of immigrants. Immigrants have no voice in the political system, and the protection of their rights is not an issue that finds support among the public at large. A diffused understanding within the public administration of the need and obligation to ensure rights protection is also lacking. Rather, it is generally—and incorrectly—believed that effective border management and immigration control are by definition contrary to the protection of the human rights of migrants and refugees. The great challenge for a European democracy is how to strike a balance and provide adequate protection, above all, of the life and dignity of the most vulnerable, and those who lack voice.

Immigrants have no voice in the political system, and the protection of their rights is not an issue that finds support among the public at large.

In terms of compliance with the ECtHR judgements concerning migrants, the Greek authorities often responded with long delay. They have tended to take minimal general measures aimed primarily at ending CM supervision rather than strengthening rights protection in the long term and changing entrenched administrative practices. As it has rightly been pointed out, the Greek authorities view the ECHR mechanism primarily “as a distant jurisdiction that requires little more than monetary compensation for the victim of the violation”.[22] Greece continues to be condemned for a large number of repeat violations relating to conditions of detention and accommodation, the treatment of migrants by police and border authorities, and deficiencies in the asylum system.

Notwithstanding its limitations, the ECHR system has played a decisive role as an external framework of judicial review and CM supervision, for the protection of human rights in Greece, even it has not eliminated many rights violations. As the overview presented above shows, adverse ECtHR judgements against Greece contributed to the adoption of significant legislative and administrative and legislative changes in immigration management. It is likely that many of those measures would not have been enacted in the absence of the ECHR external frame. However, Greece often lags behind when it comes to systematically implementing the legal changes, in ways that meet adequate standards of protection. ECHR judgments also contributed to the establishment of, and provided ongoing leverage for internal control mechanisms and human rights bodies.

The traditional concept of execution of each individual judgment is incompatible with the systemic nature of the problems that give rise to rights violations against migrants and refugees in Greece. These problems persist, wholly or partly, even after the response of national authorities is deemed satisfactory by the CM, yet, important changes occur incrementally over time. This is why Greece’s ongoing supervision by the CM, and by other international bodies such as the Council of Europe’s Committee against Torture, is important. The CM supervisory framework now provides the opportunity for non-governmental organisations to intervene in judgment implementation. Their systematic engagement with independent authorities and the National Commission at the national and at the European level is essential if the protection afforded to the rights of migrants and refugees is to be improved.

A new approach to human rights protection should focus on structural reforms in immigration and asylum and it should have the express commitment of the country’s political leadership.

Equally important is the need for a new approach in the implementation of ECtHR decisions concerning immigrants in Greece. It should focus on: (a) measures to structurally address violations at the level of administrative practices, judicial decisions and legislative reforms[23], and (b) the nurturing of a culture within the public administration that is supportive of the protection of human rights as a priority and an issue of democratic responsibility, and not as a necessary evil imposed from outside. The policy proposals below contain certain ideas and suggestions for change that could improve human rights implementation, provided that Greek governments and political forces make compliance with the ECtHR a priority.

►Strengthening and supporting the parliamentary committee for the implementation of ECtHR judgements, which should act as a central body within which parliamentary representatives regularly discuss implementation measures with the administration in different groups of ECtHR judgments.

►Coordinated action by non-governmental organisations, independent authorities and the National Commission for Human Rights, including their active participation and presence in the above parliamentary committee. This could be achieved through the creation of a network of cooperation through which their positions and proposals regarding ECtHR judgments’ implementation at the national level could be made known. A successful organisational model is provided at the European level by the European Implementation Network (EIN) in Strasbourg. The latter can be utilized more systematically to build capacity in the area of domestic judgment implementation, and to learn about best practices from other countries.

►Strengthening the institutional implementation mechanism through the creation of an inter-ministerial committee in which the competent ministries would participate, along with the Legal Council of State, the National Commission for Human Rights, and the Ombudsman; the committee would meet regularly and formulate proposals relating to implementation measures.

►Enhancing the competences of (and funding for) institutions such as the Ombudsman and the National Commission for Human Rights in the protection of the human rights of migrants and refugees.

► Intensify efforts and actions aimed at disseminating the case law of the ECtHR in the Greek judicial system and making it known to judges, as well as to selected departments in the public administration.

[1] Dia Anagnostou, The European Convention of Human Rights Regime – Reform of Immigration and Minority Policies from Afar (Routledge 2023), pp. 109-111.

[2] Greece was one of the first states to ratify the ECHR in 1953, and in 1986, it accepted the right of individual appeal to the ECtHR. Between 1969 and 1974, the Colonels’ dictatorship withdrew Greece from the Council of Europe in view of their country’s expected expulsion from it.

[3] J.G. Merrills and A.H. Robertson, Human Rights in Europe – A Study of the ECHR (Manchester University Press, 2001,4th Edition), pp. 2-5.

[4] In March 2022, the Committee of Ministers (CM) of the Council of Europe (CoE) resolved to expel Russia from the CoE (and subsequently the ECHR, too) in the light of its invasion of Ukraine last February.

[5] Anagnostou, The European Convention of Human Rights Regime, p. 57.

[6] This is an advisory state institution that adheres to the UN’s Paris Principles Relating to the Status of National Human Rights Institutions.

[7] See the relevant reports on the Ombudsman’s website at https://www.synigoros.gr/el

[8] An overview of this data per country is provided by the European Implementation Network on its website https://www.einnetwork.org/countries-overview

[9] Dougoz vs. Greece, No. 40907/98, 6 March 2001. Kaja vs. Greece, No. 32927/03, 27 July 2006. S.D. vs. Greece, No. 53541/07, 11 June 2009.

[10] Presidential Decree 90/2008 also transposed Council Directive 2005/85/EC on Asylum Procedures. Furthermore, Law 3907/2011 on the “Establishment of an Asylum Service and First Reception Service, the adaptation of the Greek law to the provisions of Directive 2008/115/EC” put in place the framework for setting up first reception structures for immigrants.

[11] Law 3900/2010 on the “Streamlining of procedures and acceleration of administrative proceedings and other provisions”.

[12] Danai Angeli and Dia Anagnostou, “A shortfall of rights and justice: Institutional design and judicial review of immigration detention in Greece,” European Journal of Legal Studies, May 2022, 97-131,” European Journal of Legal Studies, May 2022, 97-131.

[13] Law 4375/2016 on the “Organisation and operation of the Asylum Service, the Appeals Authority, the Reception and Identification Service and the General Secretariat for Reception” transposed Directive 2013/32/EU on common procedures for granting and revoking international protection status.

[14] M.S.S. v. Greece and Belgium, No. 30696/09, 21 January 2011.

[15] Rahimi v. Greece, No. 8687/08, 5 April 2011, and Housein v. Greece, No. 71825/11, 24 October 2013.

[16] Law 3907/2011 on the Establishment of Asylum Service and Service of first reception, adaptation of Greek legislation with the provisions of Directive 2008/115/EC “concerning common rules and procedures in Member States for the returning of illegally staying third-country nationals”.

[17] For a thorough analysis of the issue, see Anagnostou, The European Convention of Human Rights Regime, p. 176-183 and 194-197.

[18] CM/Del/Dec(2019)1348/H46-9, M.S.S. and Rahimi groups v Greece, 1348th meeting, 6 June 2019.

[19] Makaratzis v. Greece, No. 50385/99, 20 December 2004.

[20] The first mechanism proposed by the Greek authorities in 2011 for investigating such incidents did not meet basic international standards and rights protection. See Nikolaos Sitaropoulos, “Migrant Ill-treatment in Greek Law Enforcement-Are the Strasbourg Court Judgments the Tip of the Iceberg?”, European Journal of Migration and Law 19 (2017) 136-164, pp. 151.

[21] Committee of Ministers’ Notes/1411/H46-15 16, Makaratzis group v. Greece (Application No. 50385/99), 1411th meeting, 14-16 September 2021.

[22] Konstantinos Tsitselikis, “Καθρεφτίζοντας τις πολλαπλές ελληνικές πραγματικότητες: Οι υποθέσεις αλλοδαπών κατά της Ελλάδας ενώπιον του ΕΔΔΑ” [Reflecting multiple Greek realities: The cases brought against Greece by aliens before the ECtHR], Ευρωπαϊκή Ολοκλήρωση, Ευκαιρίες για τη Νεολαία – Δικαστική Προστασία και Θεμελιώδη Δικαιώματα [European Integration, Opportunities for Young People – Judicial Protection and Fundamental Rights], ed. Despina Anagnostopoulou, University of Macedonia Press, 2022, p. 438-9.

[23] Tsitselikis, “Καθρεφτίζοντας τις πολλαπλές ελληνικές πραγματικότητες” [Mirroring the multiple Greek realities], pp. 438-9.