- One year on from the Versailles Declaration, we are mapping EU defence collaboration by analysing:

- EU Member-states’ engagement in initiatives within the EU structures with a focus on the European Defence Fund (EDF) and the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) projects

- Bilateral and minilateral defence collaboration outside the EU framework

- Intra-EU arms procurement, with a focus on the main ‘producers’ and ‘consumers’ in the emerging EU arms market space

- France is the indisputable leader in EU defence collaboration, both within the EU institutional framework (PESCO and EDF alike) and with regard to bilateral and plurilateral schemes outside it. Followed closely by Italy, Spain, Germany and Greece, they form the vanguard group, which could constitute the inner core of any future EU defence integration venture.

- Through EDF, the Commission is forging ahead and supporting financially closer collaboration between the defence industries of EU member-states. In the absence of far-reaching industrial cooperation schemes outside the EU framework, the economic considerations of intra-EU defence collaboration weigh ever more heavily on the mindset of many national governments.

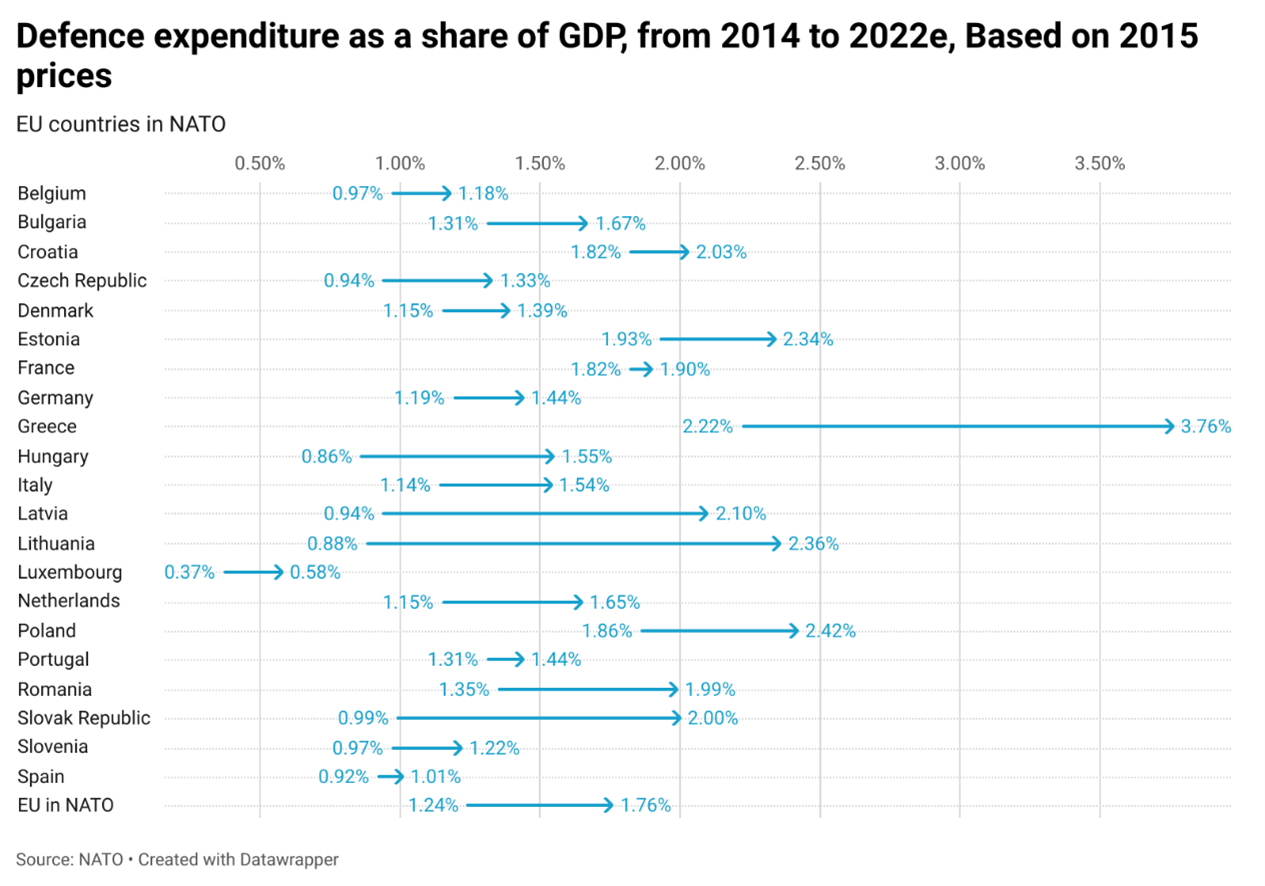

- These considerations are further reinforced by the continuous increase over the last decade of the defence expenditure of EU member-states as a percentage of their GDP. All EU member-states have increased their defence budgets, to varying degrees.

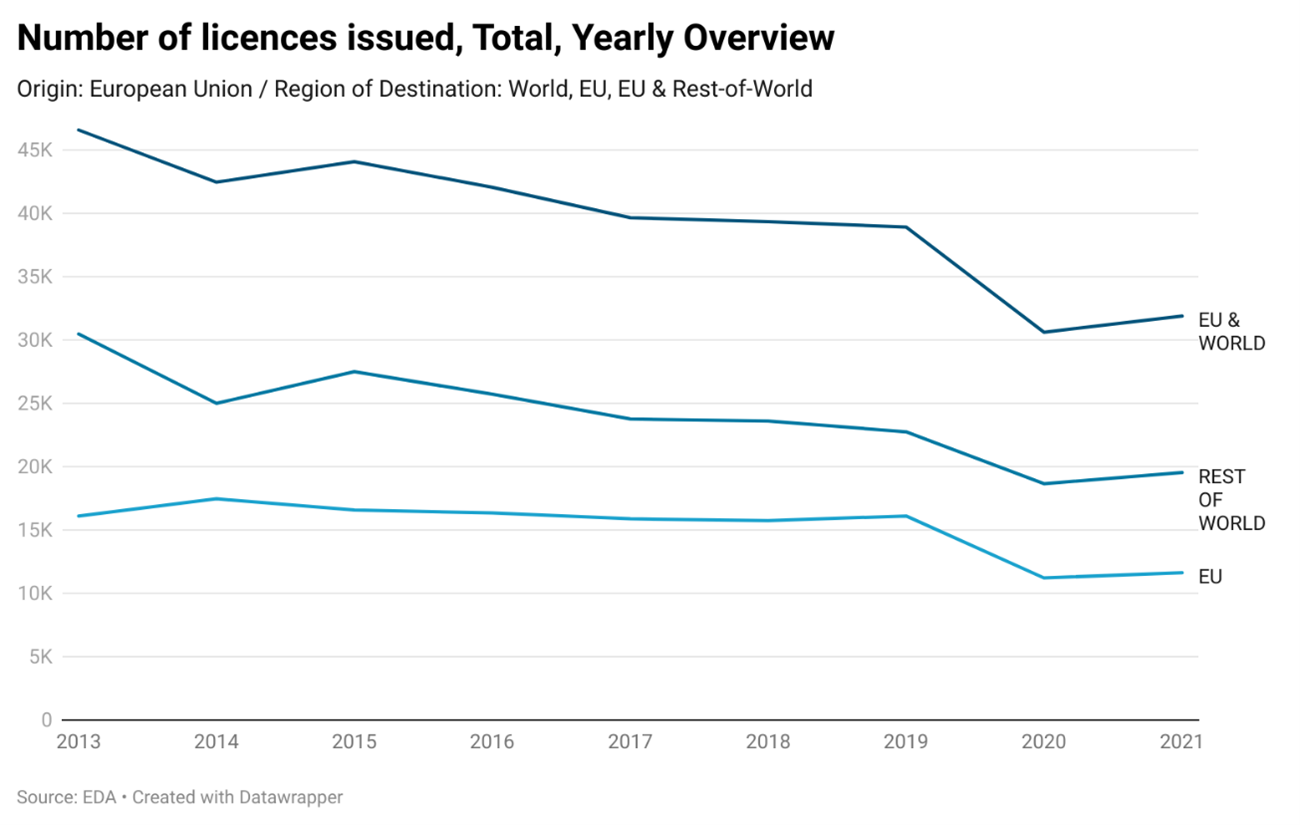

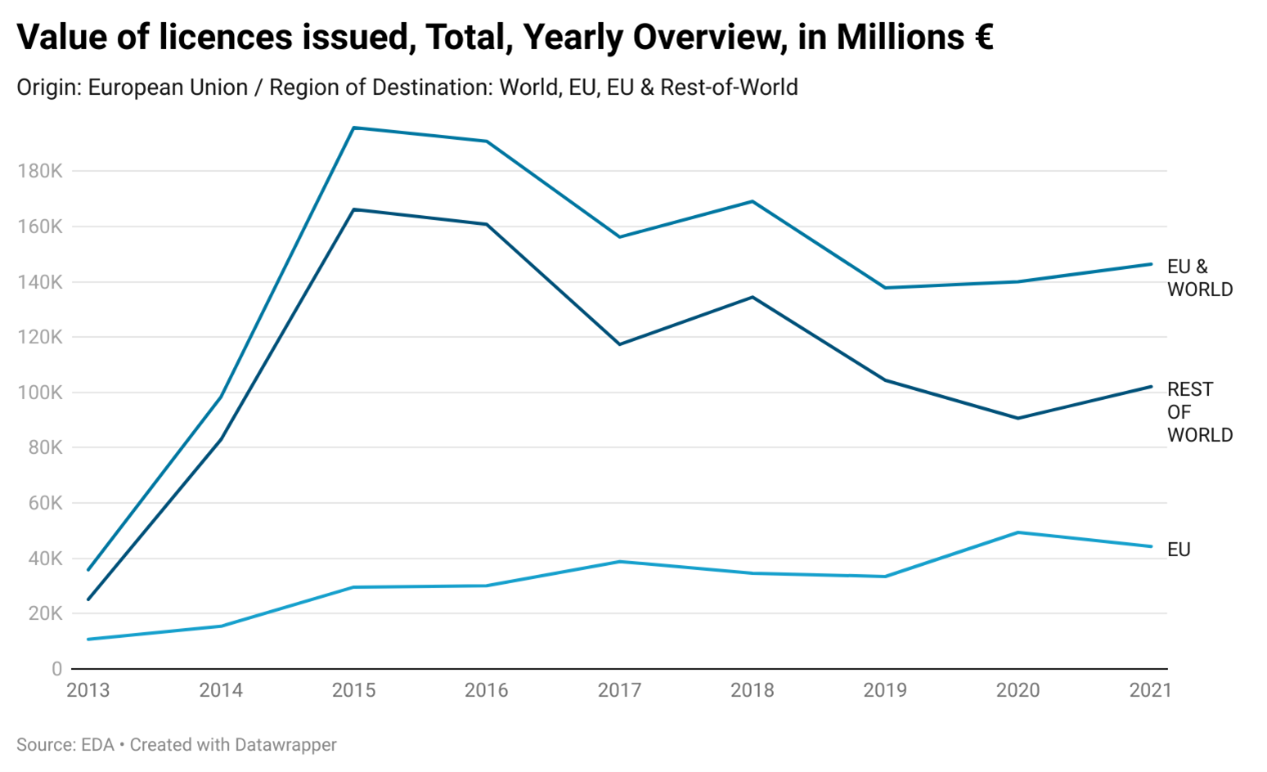

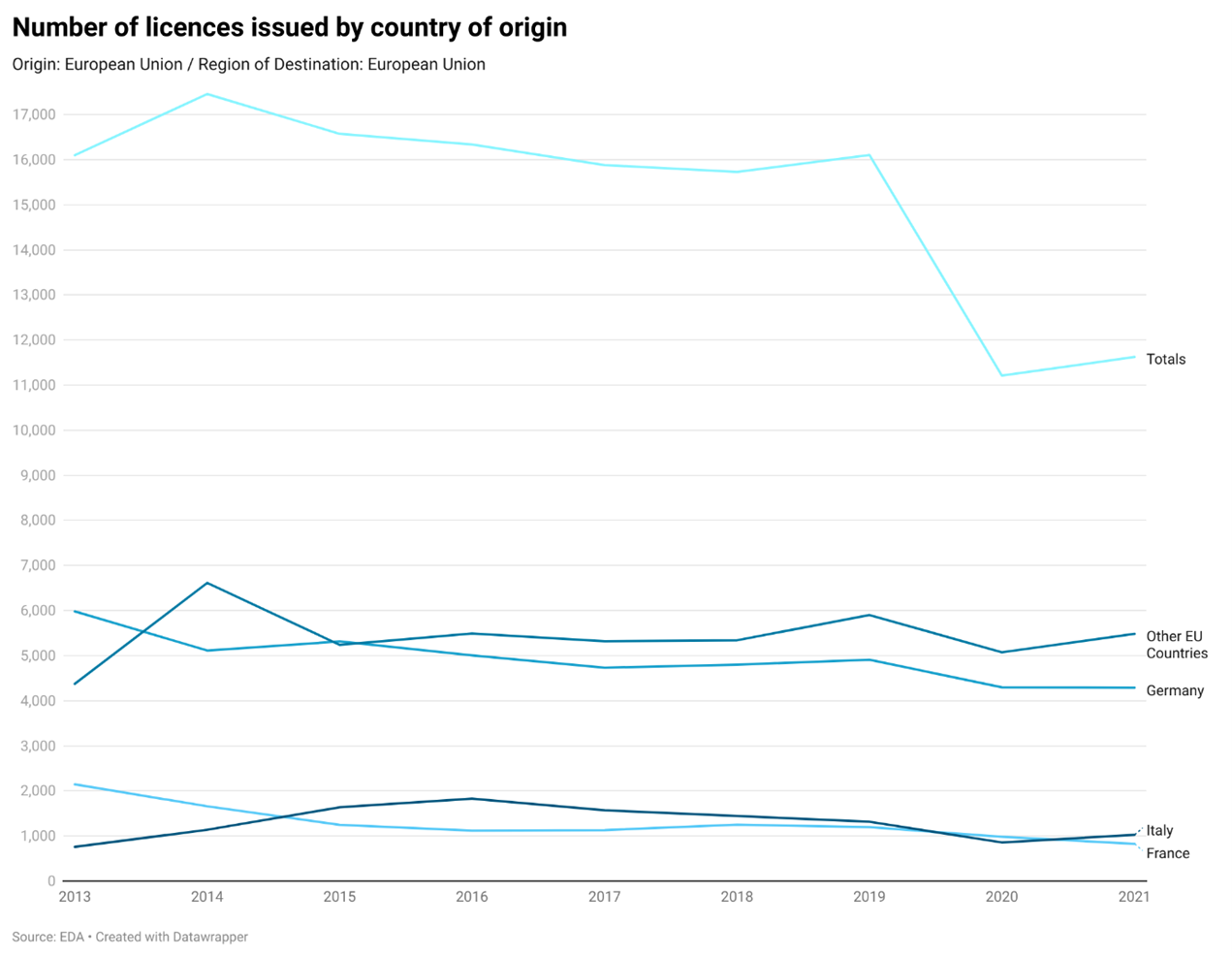

- The European defence industry is shrinking in terms of the number of licences issued, but thriving in terms of their value, which almost tripled between 2013 and 2021. France, Germany, Italy and Spain account for the lion’s share of licences issued with an EU destination. In terms of license value, the top exporters are France, Germany, Poland and Spain, with France alone accounting for sixty four percent (64%) of the overall value of all licences issued in 2021. Together, these four countries account for over ninety-three per cent (93%) of the overall value of licences exported to an intra-EU destination. In terms of intra-EU imports, Germany, Greece and France top the list of ‘consumers’ in terms of the five-year average for 2016-21.

Read here in pdf the Policy paper by Spyros Blavoukos, Professor, Athens University of Economics and Business, Head of the ‘Ariane Condellis’ European Programme at ELIAMEP; Panos Politis-Lamprou, Junior Researcher, ELIAMEP and Thanos Dellatolas, Research Assistant, ELIAMEP.

Introduction

The Versailles Declaration, adopted at the informal meeting of the EU Heads of State or Government in March 2022, has significantly raised expectations for tangible progress in the field of European defence integration. Only a few weeks after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the EU member-states agreed on the need to bolster their defence capabilities in a joined up, articulated way. The agreement entailed a substantial increase in defence expenditure with new and advanced military capabilities being developed in a collaborative way and with a focus on identified strategic shortfalls. Russian aggression played a catalytic role in highlighting and accentuating Europe’s security dilemmas: Not only did the invasion break the taboo on providing lethal arms by using the European Peace Facility (EPF) to arm Ukraine, it also set in motion a broader spiralling dynamic of strengthening European defence, either individually or collectively. Collectively, the EPF activation has been showcasing European solidarity with Ukrainian resistance, alongside the extensive sanctions regime imposed on Russia. Individually, acknowledging the large gaps in European defence and the urgent need to fill them, many EU member-states have increased their national defence budgets to reinforce their deterrent capacity.

One year on from Versailles, we need to take stock of the existing frameworks for defence collaboration between EU member-states and explore their potential synergies.

One year on from Versailles, we need to take stock of the existing frameworks for defence collaboration between EU member-states and explore their potential synergies. Such collaboration exists both within the EU institutional structure (EDF, EDIRPA, EPF, EDA, PESCO projects, CSDP operations and missions, European Rapid Deployment Capacity / EU Battlegroups) and outside it, in bilateral or minilateral formats (like the existing multinational military structures /commands and the 2021 defence agreement between France and Greece or the 2023 Franco-Spanish Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation). Collaboration may have an operational or economic/industrial dimension, without excluding hybrid schemes that combine both. The operational dimension entails military collaboration ‘in the field’, whether this be tried, tested and ongoing (e.g., existing military formations and units, on paper or in action) or prospective (e.g., a binding defence clause). The economic/industrial dimension entails agreements that aim to foster economic and/or industrial cooperation, including inter alia the co-development and co-production of armaments as well as joint military purchases. Finally, the volume of the arms trade between the EU member-states is another indirect indication of defence collaboration that we are incorporating into our analysis. The underlying rationale is that the procurement of military equipment, especially at volume, suggests close political ties and an increased level of interoperability between armed forces, which in turn entails a potential for closer defence collaboration, or at least for an emerging European defence market.

This paper, which is the abridged version of a longer and more comprehensive one analysing in greater length intra-EU defence collaboration, is divided into five parts: Following this brief introduction, the second part presents and discusses two of the most significant collaborative schemes that currently operate within the EU framework: namely, EDF and PESCO. Although the other extant schemes are not underestimated, this focus allows the EU member-states to be clustered into three groupings according to their degree of engagement in defence collaboration within the EU structures: the ‘vanguard’, the ‘lukewarmers’ and the ‘loiterers’. The third part provides an overview of the active schemes that exist outside the EU framework. Though the list is not exhaustive, it is quite representative in the sense that it maps a dense network of military collaborative interactions ranging from a bilateral arms trade to defence pacts. The fourth part examines the volume of the intra-EU arms trade, highlighting the ‘producers’ and the ‘consumers’ in the emerging European defence market. We conclude by bringing together the insights from the previous analysis and highlighting the key findings and the road ahead.

Our main findings are the following:

- Unsurprisingly, France is the indisputable leader in EU defence collaboration, both within the EU institutional framework (PESCO and EDF alike) and with regard to bilateral and plurilateral schemes outside it. Followed closely by Italy, Spain, Germany and Greece, they form the vanguard group, which could constitute the inner core of any future EU defence integration venture.

- Through EDF, the Commission is forging ahead and supporting financially closer collaboration between the defence industries of EU member-states. In the absence of far-reaching industrial cooperation schemes outside the EU framework, the economic considerations of intra-EU defence collaboration weigh ever more heavily on the mindset of many national governments.

- These considerations are further reinforced by the continuous increase over the last decade of the defence expenditure of EU member-states as a percentage of their GDP. All EU member-states have increased their defence budgets, to varying degrees.

- The European defence industry is shrinking in terms of the number of licences issued, but thriving in terms of their value, which almost tripled between 2013 and 2021. France, Germany, Italy and Spain account for the lion’s share of licences issued with an EU destination. In terms of license value, the top exporters are France, Germany, Poland and Spain, with France alone accounting for sixty four percent (64%) of the overall value of all licences issued in 2021. Together, these four countries account for over ninety-three per cent (93%) of the overall value of licences exported to an intra-EU destination. In terms of intra-EU imports, Germany, Greece and France top the list of ‘consumers’ in terms of the five-year average for 2016-21.

Defence Collaboration within the EU Institutional Framework

European Defence Fund (EDF)

Juncker’s vision for common military assets, some of them even owned by the EU, was never materialized, since a mechanism for collective military procurement or a pool of military resources have yet to be put in place.

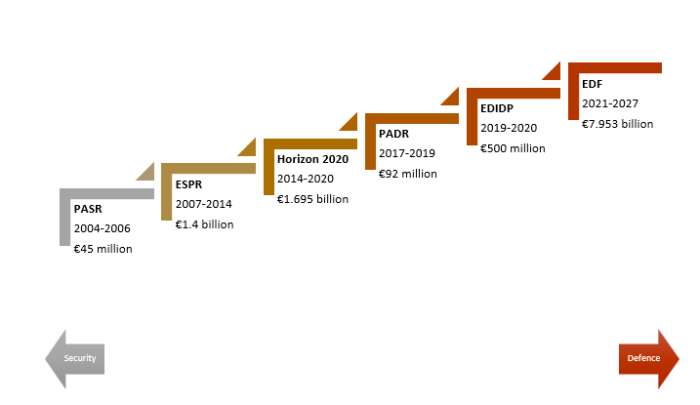

In April 2021, Regulation 2021/697 officially established the European Defence Fund (EDF), a new milestone in EU defence collaboration. It is the culmination of a long-term effort by the Commission to support the European defence industry (Figure 1). Successive schemes have included the Preparatory Action for Security Research (PASR) in 2004, which served as the test-case for the creation of the European Security Research Programme (ESPR) in 2007. Both programmes focused on security research projects and included dual-use technologies, which brought the fields of security (terrorism, crime, borders and infrastructures) and defence (duality of technologies; civil and military) closer together (Lavallée, 2011, p. 376). In the 2014-20 Framework Programme, civil security research was further reinforced through the Horizon 2020 programme (Csernatoni, 2021, p. 32). The Barroso Commission pushed for research funding programmes which focused explicitly on defence rather than security, but member-states did not support such actions (Hoeffler, 2023, pp. 13-14). It was only under Juncker’s Presidency that the European Defence Action Plan (EDAP) was launched, with two preparatory projects: the Preparatory Action on Defence Research (PADR) and the European Defence Industrial Development Programme (EDIDP), which were established in 2017 and 2019 respectively (Harroche, 2020, pp. 853-854). Both actions were replaced by the EDF in the 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF), entailing a substantial upgrade in terms of allocated funds. However, Juncker’s vision for common military assets, some of them even owned by the EU, was never materialized, since a mechanism for collective military procurement or a pool of military resources have yet to be put in place (Hoeffler, 2023, p. 17).

Figure 1: Evolution of EU funding programmes for security & defence R&D until the launch of EDF

Sources: Oikonomou, 2009; European Commission, 2014; European Commission, 2017; European Commission, 2019

The Fund is underpinned by a supranational political logic, with almost eight billion Euros put at the disposal of the EU for research, development and supporting defence-related collaborative projects.[1] This sum is being directed at seventeen thematic (e.g., ground, naval and air combat) and horizontal (disruptive technologies and innovative defence technologies for small and medium size enterprises (SMEs)) action categories in the current MMF. The main objective of this new financial tool is to strengthen the competitiveness of the European defence industry by means of more, smarter and collective investment aimed at building economies of scale and avoiding costly duplications. EDF operates through annual work programmes on the basis of which specific calls for proposals are issued each year.[2] According to the Regulation 2021/697, the co-financing rate can reach up to 100%, except in the case of the system prototyping and the testing/qualification/certification of a defence product, for which the maximum rates are 20% and 80% respectively. Additional funding rates exist for PESCO projects and projects in which SMEs and mid-caps take part.

The EDF’s overall funding may be considered modest in comparison to the MFF’s overall budget of €1.074 trillion and to most of the respective national investments. However, at the EU level, the EDF’s eligibility criteria and governance model can become a game changer not only for the European defence technological and industrial base (EDTIB), but also for the defence dimension of the European project. The aspirations for a real Defence Union may come true through the backdoor of economic and industrial cooperation. The de facto expansion of the Commission’s competence in the field of defence is evident in the preamble to the relevant Regulation 2021/697. It refers to Article 173(3) of TFEU, which allows the Union to contribute under certain conditions to the existence of a competitive European industry. Even if the EDF is essentially a defence-related initiative, its legal basis is not based on the provisions on the Common Security and Defence Policy but rather on those of EU industrial policy (Alexis, 2022, p. 2).

The EDF operates on the basis of eligibility criteria that can be divided into two main categories: a) the country of origin of each entity, and b) the number of entities in a consortium (Articles 9 and 10). Regarding the former, only contractors from and located in the EU or an associated country’s territory are eligible, with the notable exception of Norway. The participating entities should not be controlled by (entities from) third countries. As far as the latter is concerned, based on the EDF’s goal of fostering defence industrial cooperation, only consortiums that consist of entities originating from three or more different member-states (or associated countries) are eligible. At least three of those entities, established in two or more member-states (or associated countries), should not control each other. The underlying rationale is the building of multi-country consortiums and the widest possible dispersion of the funding pie.

In terms of governance, the EDF is clearly supranational in nature, with member-states in the back seat. They designate representatives to the EDF Programme Committee, together with personnel from the European Defence Agency (EDA) and the European External Action Service (EEAS). These representatives assist the Commission in the annual work programmes, but are excluded from the processes whereby the proposals are evaluated and selected. Rather, it is the Commission, with the support of appointed independent experts, that is responsible for the ethics screening and assessment, as well as for the selection of the actions to be funded. The list of selected independent experts is not made public, leaving no room for interference from national capitals (Brichet et al., 2021, p. 3).

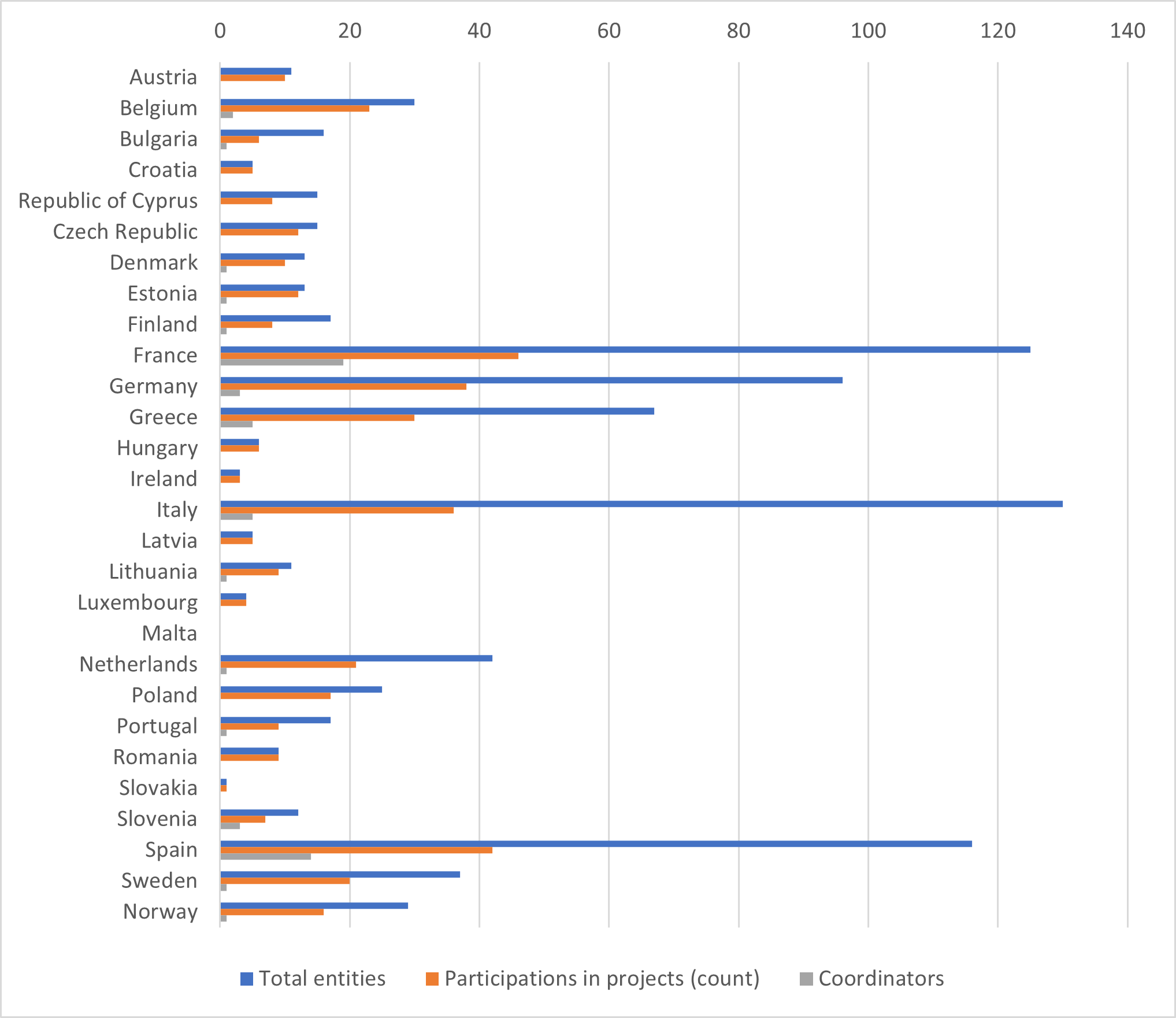

Italy is the country with the most participating entities, followed by France, Spain, and Germany. Revealing a noteworthy dynamism and potential, Greece is ranked fifth, with sixty-seven entities included in at least one consortium which benefits from EDF funds. […] French and Spanish entities are well ahead of the field, suggesting a significant dynamism within their defence industries, which are also both willing and ready to take advantage of the opportunities to which EDF has given rise. Greek entities are also quite active, taking the coordinator role in five projects.

Table 1 and Figure 2 provide an overview of the dynamics of EDF operation regarding the total number of participating entities, their countries of origin, the number of projects they are engaged in, as well as any coordinating role they may have undertaken. With the exception of Malta, entities from all other EU member-states (plus Norway) have joined one or more consortiums. Italy is the country with the most participating entities, followed by France, Spain, and Germany. Revealing a noteworthy dynamism and potential, Greece is ranked fifth, with sixty-seven entities included in at least one consortium which benefits from EDF funds. In terms of the number of projects these entities participate in, the French entities come in first, followed by their Spanish, German, Italian, and Greek counterparts. In terms of coordination roles, which indicate the participating entities’ leadership role and potential, French and Spanish entities are well ahead of the field, suggesting a significant dynamism within their defence industries, which are also both willing and ready to take advantage of the opportunities to which EDF has given rise. Greek entities are also quite active, taking the coordinator role in five projects. Despite the large number of Italian entities which participate in funded projects, the number of projects they lead is very small: just five, equal to the number of Greek-led projects. German entities do even worse, leading just three projects (the same number as Slovenia). What clearly emerges from these figures is a core group of five countries, which include Greece, whose defence industries are active at the European level and which could potentially drive the conglomeration of the European defence industry.

Table 1: European Defence Fund participation performance

| Country | Total entities | Participations in projects (count) | Coordinators |

| Austria | 11 | 10 | 0 |

| Belgium | 30 | 23 | 2 |

| Bulgaria | 16 | 6 | 1 |

| Croatia | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Republic of Cyprus | 15 | 8 | 0 |

| Czech Republic | 15 | 12 | 0 |

| Denmark | 13 | 10 | 1 |

| Estonia | 13 | 12 | 1 |

| Finland | 17 | 8 | 1 |

| France | 125 | 46 | 19 |

| Germany | 96 | 38 | 3 |

| Greece | 67 | 30 | 5 |

| Hungary | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| Ireland | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Italy | 130 | 36 | 5 |

| Latvia | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Lithuania | 11 | 9 | 1 |

| Luxembourg | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Malta | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Netherlands | 42 | 21 | 1 |

| Poland | 25 | 17 | 0 |

| Portugal | 17 | 9 | 1 |

| Romania | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| Slovakia | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Slovenia | 12 | 7 | 3 |

| Spain | 116 | 42 | 14 |

| Sweden | 37 | 20 | 1 |

| Norway | 29 | 16 | 1 |

Figure 2: EU Member-States’ participation in EDF

Source: European Defence Fund, 2023

Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO)

Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) constitutes a form of differentiated integration in the field of security and defence, as defined by Article 42(6) of TEU. Article 46 outlines the procedures by which a member-state can participate in and withdraw from this permanent structured cooperation, and Protocol 10 defines the objectives along with the measures that have to be undertaken within this framework. Although the provisions already existed in the Lisbon Treaty, PESCO was officially launched in December 2017, when the participating member-states agreed on five core legally-binding commitments: increased defence investments (20% of their total military expenditures); common defence apparatus (harmonized requirements for capability development projects); the enhanced availability, interoperability, flexibility and deployability of their armed forces; closer cooperation for the common good; and the joint development of equipment programmes under the auspices of EDA (Fabry, Koenig, & Pellerlin-Carlin, 2017).

Before its awakening in December 2017, PESCO was the “sleeping beauty” of European defence collaboration (Nováky N., 2018, p. 1; Juncker, 2017; Fiott, Missiroli, & Tardy, 2017, p. 7; Benavente, 2017; Mauro, 2015). There had been two earlier attempts to bring PESCO back from the dead: the first was in a 2010 non-paper by Belgium, Hungary and Poland; the second in a request by Italy and Spain to the then HR/VP Baroness Catherine Ashton to add PESCO to the agenda of the Foreign Affairs Council meeting (Blockmans, 2018, pp. 1808-1809). The Brexit referendum gave new impetus to PESCO, as indicated by the Franco-German 2016 non-paper which identified PESCO as a means to meeting the objectives outlined in the EU Global Strategy (Mauro & Santopinto, 2017, p. 14). In July 2017, France, Germany, Italy and Spain put forward a proposal for an inclusive and ambitious PESCO, a proposal that was also endorsed by Belgium, the Czech Republic, Finland and the Netherlands (Zandee, 2018, p. 2). The launch of PESCO became possible only after the convergence of the different strategic cultures of France and Germany: the former had advocated the formation of an exclusive coalition comprising a select few member-states possessing the requisite willingness and capability to move forward jointly; the latter had espoused the establishment of an open framework for cooperation based on inclusion, future commitment, benchmarks and deliverables (De France, 2019, p. 8-9; Fiott, Missiroli, & Tardy, 2017, p. 21).

PESCO’s intergovernmental nature is explicitly mentioned in the Protocol, which references the primacy of member-states, underscoring the fact that participating member-states remain at the centre of the decision-making process. The HR/VP and subordinate agencies, namely EDA and EEAS, shall play a supportive and coordinating role. There are currently 25 participating member-states in PESCO projects. Following a referendum held in summer 2022, Denmark is set to join PESCO. Malta is the only EU member-state not currently participating, but the nation may apply in the future if PESCO focuses on coordinating arms procurement and does not become more militarized (Lazarou & Friede, 2018, p. 6; Blockmans & Crosson, 2021, p. 91). Although participation is open to third states under certain conditions, project members decide on whether to accept or reject additional countries as project members or observers.[3]

The PESCO architecture entails a projects-based design, with 60 projects having been launched in four release waves: 17 in the first (March 2018) and second (November 2018), 13 in the third (November 2019), and 14 in the fourth (November 2021) (Martill & Gebhard, 2023, p. 111).[4] In May 2023, the Council will select the next projects to be launched as part of the fifth wave. These projects fall into seven military domains, as depicted in Image 1.

Image 1: Number of ongoing PESCO projects per domain

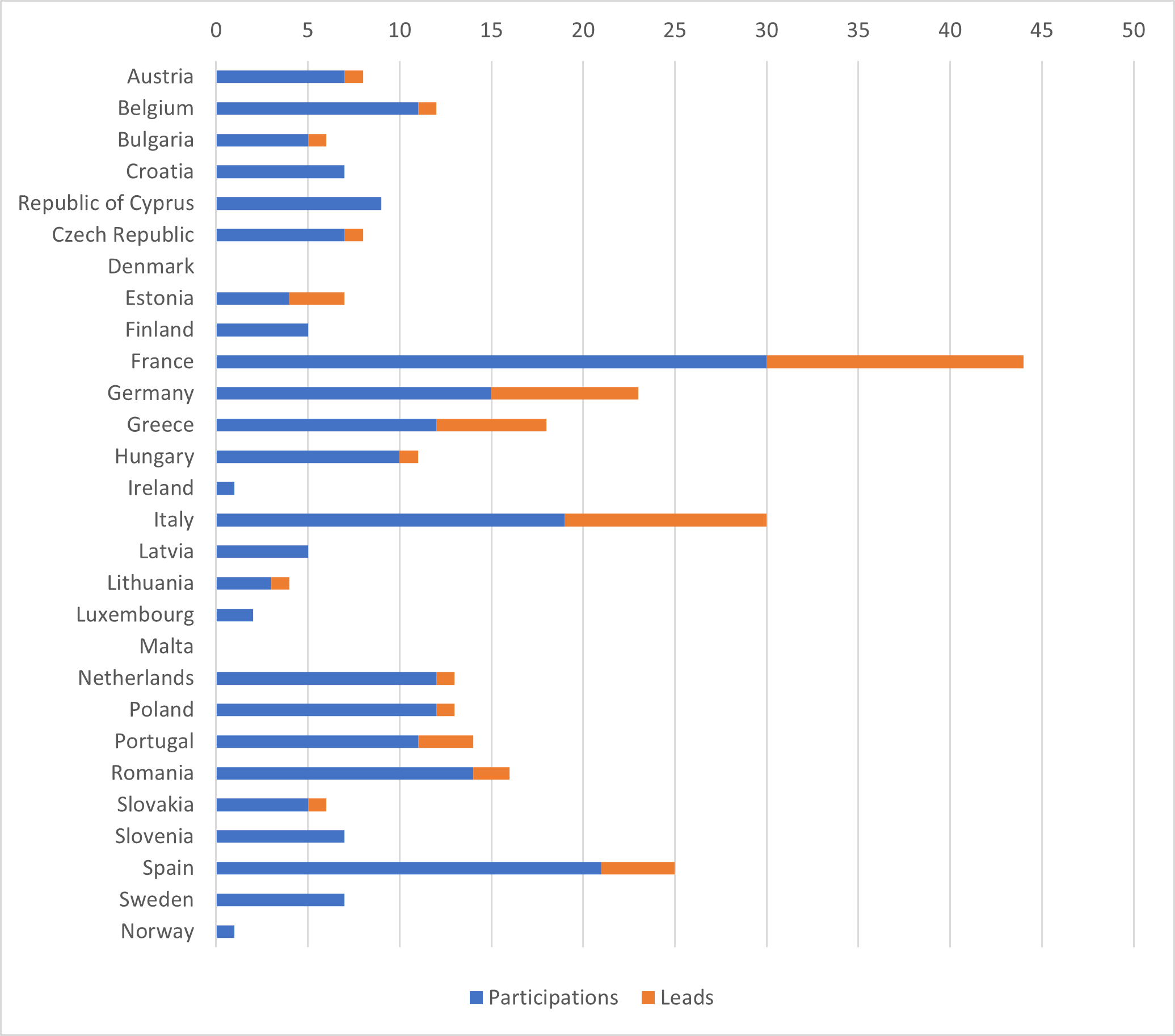

France is the undisputed leader in this collaborative framework, followed by Italy, Spain, Germany and Greece.

Table 2 and Figure 3 provide an overview of the commitment of EU member-states to PESCO, as illustrated by the number of projects they join and lead. France is the undisputed leader in this collaborative framework, followed by Italy, Spain, Germany and Greece. Paris tends to participate in projects related to the development of joint capabilities, while its interest in maritime and air projects stems from its sophisticated defence industry in these areas. Rome is also interested in building joint capabilities, albeit with a distinct emphasis on land and cyber security systems. Madrid is similar to Paris, albeit with a comparatively greater emphasis on shared capabilities. Berlin focuses on air and cyber security capabilities, while Athens prioritizes maritime and land projects.

Table 2: Participation in PESCO Projects and Lead Roles

| Country | Participations | Leads |

| Austria | 7 | 1 |

| Belgium | 11 | 1 |

| Bulgaria | 5 | 1 |

| Croatia | 7 | 0 |

| Republic of Cyprus | 9 | 0 |

| Czech Republic | 7 | 1 |

| Denmark | 0 | 0 |

| Estonia | 4 | 3 |

| Finland | 5 | 0 |

| France | 30 | 14 |

| Germany | 15 | 8 |

| Greece | 12 | 6 |

| Hungary | 10 | 1 |

| Ireland | 1 | 0 |

| Italy | 19 | 11 |

| Latvia | 5 | 0 |

| Lithuania | 3 | 1 |

| Luxembourg | 2 | 0 |

| Malta | 0 | 0 |

| The Netherlands | 12 | 1 |

| Poland | 12 | 1 |

| Portugal | 11 | 3 |

| Romania | 14 | 2 |

| Slovakia | 5 | 1 |

| Slovenia | 7 | 0 |

| Spain | 21 | 4 |

| Sweden | 7 | 0 |

| Norway | 1 | 0 |

Figure 3: Participation in PESCO Projects and Lead Roles

Source: Council of the EU, 2021

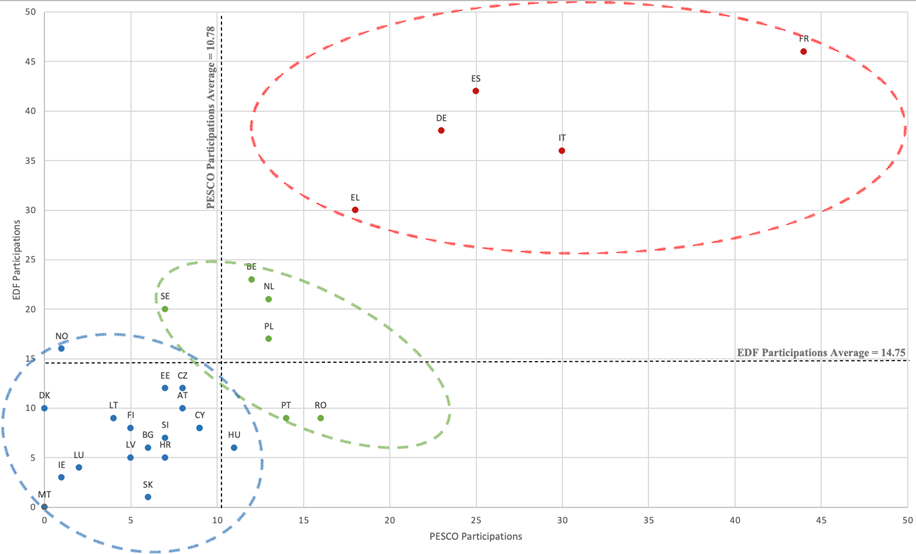

Three Clusters of Defence Collaboration within the EU

A combined analysis of EDF and PESCO enables EU member states to be placed in three clusters vis-à-vis their engagement and interest in collaborative initiatives of this sort (Figure 4). The levels of participation in the EDF are determined by the number of projects in which at least one entity from a given country is involved, rather than by the total number of entities participating across the board. However, the levels of participation in PESCO are based on the total number of participations in projects, including lead roles.

Figure 4: PESCO participations and EDF involvement

The ‘Vanguard’

Which countries can be said to be leading European defence collaboration? A group of five countries constitute the vanguard. France is the most active player in the field, in terms both of PESCO participation and of capitalising on the economic and industrial cooperative framework provided by EDF. This is further reinforced by France’s leading role in CSDP military operations, especially in Africa, which is not discussed here. Italy and Spain follow the French lead, with the former more active within the PESCO framework and the latter more active in positioning its national defence industry through EDF. Given its political importance and economic/industrial magnitude, Germany could not be missing from this group, but it follows developments rather than taking the lead. Greece’s presence is not surprising, given its security concerns and the diplomatic diversification of the security portfolio it has consciously adopted to maximise its deterrent capacity.

The ‘Lukewarmers’

In the broader discourse on climate change, ‘lukewarmers’ are identified as those who believe in climate change but do not consider it a potentially catastrophic phenomenon. Used here, this neologism refers to those EU member-states that see some merit in the EU defence integration process but are not enthusiastic about it for a range of reasons. Poland identifies the potential benefits of European defence cooperation, but its traditional Russia-focused security concerns, heavily reinforced by current developments, lead it to assign primacy to the US and to NATO. The Netherlands aspires to foster its defence industry, which focuses heavily on high-tech, dual-use systems and depends largely on exports (Zandee, 2019, pp. 3-4). Sweden’s entities are exhibiting a growing assertiveness, partly because of the country’s traditionally large defence industry (Olsson, 2019, p. 4). Obviously, developments regarding Sweden’s NATO membership will also affect the country’s stance on European defence collaboration. Finally, Romania has a promising industrial base and is actively seeking funding within the PESCO and EDF frameworks to support its numerous small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and start-ups which focus on IT and produce dual-use goods (Latici, 2020, p. 4).

The ‘Loiterers’

This third cluster includes those EU member-states–more than half of the whole- that have yet to show any significant interest in the ongoing initiatives. This group is characterised by heterogeneity, since it includes member-states that have traditionally kept their distance from defence collaboration (like Denmark, Malta and Ireland) as well as those that seek to maintain a degree of neutrality (namely Austria). It also includes small countries with few military resources or weak defence industry (like Bulgaria, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania and Luxembourg) and medium-size states that welcome the European defence funding opportunities without this prejudicing the primacy of NATO (like the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Slovenia). It will be interesting to see if Estonia and Finland increase their engagement in the aftermath of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

Defence Collaboration Outside the EU Framework

Defence partnerships between EU member states, with or without the participation of third countries like the US, create a dense network of defence interactions of various intensity and depth.

Defence partnerships between EU member states, with or without the participation of third countries like the US, create a dense network of defence interactions of various intensity and depth (Andersson, 2023). Their members may overlap, but each partnership has distinctive features and builds on different drivers, which may include geographical proximity, similar strategic cultures, and/or shared technological or industrial interests. While some partnerships are very traditional, top-down general agreements, many European defence collaboration efforts are now bottom-up and demand-driven with a focus on maintaining or developing key defence capabilities (Andersson, 2015).

Our analysis distinguishes between three different types of defence agreements: a) agreements with an explicit defence clause, which usually bring together both the operational and the industrial branches of the signing parties in a comprehensive and far-reaching way; b) agreements with a specific military or industrial focus; and c) agreements, including letters of intent and accords, which have potential but have not yet been substantially implemented.

The Mediterranean region clearly emerges as a focal point for defence-related interactions. Three out of four agreements entailing deep defence collaboration have been signed by EU Mediterranean states, the fourth being a revised and updated version of the agreement which has underpinned the Franco-German axis for six decades. France holds the key in all four agreements.

Without going into the details of the different partnerships presented indicatively in Table 3, the Mediterranean region clearly emerges as a focal point for defence-related interactions (Group A). Three out of four agreements entailing deep defence collaboration have been signed by EU Mediterranean states, the fourth being a revised and updated version of the agreement which has underpinned the Franco-German axis for six decades. France holds the key in all four agreements, which reinstate France’s geopolitical role and interest in the region as well as capturing its converging security concerns with the other three main Mediterranean countries, in particular. Theoretically, these agreements’ overlapping membership creates a deep regional defence collaboration network in the Mediterranean with binding defence commitments indicative of French aspirations in the region.

The BeNeLux trio is dominant in four of them, creating another distinct nexus of defence cooperation. The Southern rim features only one such scheme (EUROMARFOR), with France and Italy taking the lead and Spain and Portugal participating, while the Nordic countries (Finland, Sweden and Denmark) collaborate within the loose framework of NORDEFCO, together with Norway. Franco-German collaboration can be seen in two such schemes (EUROCORPS and the European Air Transport Command), bringing on board other EU members as well.

At the same time, there are a plethora of enhanced military cooperation schemes (Group B). Without claiming that the list is exhaustive, it nonetheless provides some indications about the state of operational ‘in-the-field’ collaboration between EU member-states. The BeNeLux trio is dominant in four of them, creating another distinct nexus of defence cooperation. The Southern rim features only one such scheme (EUROMARFOR), with France and Italy taking the lead and Spain and Portugal participating, while the Nordic countries (Finland, Sweden and Denmark) collaborate within the loose framework of NORDEFCO, together with Norway. Franco-German collaboration can be seen in two such schemes (EUROCORPS and the European Air Transport Command), bringing on board other EU members as well. It is too early to assess the European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI), and the same holds for the Air Force Cooperation between the Nordic countries announced in March 2023.

Most of these agreements and collaborations remain on paper and not much can be said about their practical implementation. Although the potential of many such agreements is high, their lack of an explicit modus operandi generates concern about their operational—or, rather, political–rationale.

The last category includes schemes that have yet to demonstrate their usefulness or role within the European defence architecture (Group C). Most of these agreements and collaborations remain on paper and not much can be said about their practical implementation. Although the potential of many such agreements is high, their lack of an explicit modus operandi generates concern about their operational—or, rather, political–rationale. For example, the French-led European Intervention Initiative (EI2) resembles a more flexible PESCO and illustrates the French investment in collaborative defence schemes both within and outside the EU institutional framework. An obvious question is what added value such initiatives bring, along with the degree of potential duplication they may give rise to. France seeks to keep both intra- and extra-EU paths of defence collaboration open as credible alternatives to each other, and has no intention of putting all its eggs in the same basket. Which path it eventually follows will depend on the future dynamics of European defence collaboration.

Table 3: Plurilateral/bilateral schemes of defence cooperation in Europe

| Group A – Partnerships with defence clauses | ||||||||

| Treaty Name | Party A | Party B | Year | Defence clause – Bilateral | Reference to mutual assistance clause – EU (A. 42(7) TEU) | Reference to defence clause – NATO | ||

| Franco-Greek Defence Agreement | France | Greece | 2021 | Article 2 | – | Article 3 | ||

| Treaty of Aachen | France | Germany | 2019 | Article 4.1 | Article 4.1 | Article 4.1 | ||

| Franco-Spanish Friendship Treaty | France | Spain | 2023 | – | Article 9.2 | Article 9.2 | ||

| Quirinal Treaty | France | Italy | 2021 | – | Article 2.1 | Article 2.1 | ||

| Group B – Enhanced military cooperation schemes | ||||||||

| Scheme Name | Party A | Party B | Other parties | Year | Multinational command | Pool of personnel & resources | ||

| Belgian-Luxembourg reconnaissance battalion | Belgium | Luxembourg | – | 2030 | Binational command | Yes | ||

| BeNeSam | Belgium | Netherlands | – | 1996 | Binational command | Yes | ||

| BeNeLux Air Defence | Belgium | Netherlands | Luxembourg | 2015 | No | No | ||

| EUROCORPS | France | Germany | Belgium, Luxembourg, Poland, Spain | 1992 | Yes | Yes | ||

| European Air Transport Command (EATC) | France | Germany | Belgium, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Spain | 2010 | Yes | Yes | ||

| Belgium-Luxembourg Binational Air Transport Unit | Belgium | Luxembourg | – | 2020 | Binational command | Yes | ||

| EUROMARFOR | France | Italy | Spain, Portugal | 1995 | When deployed | No standing forces | ||

| European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI) | Germany | UK | Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Netherlands, Norway, Romania Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, | 2022 | No | No | ||

| NORDEFCO | Finland | Sweden | Denmark, Norway | 2009 | No | No | ||

| Motorized Capacity (CaMo) | Belgium | France | – | 2018 | No | No | ||

| Nordic Air Force Cooperation | Denmark | Finland | Norway, Sweden | 2023 | Possibly yes | Possibly not (yet) | ||

| Group C – Secondary schemes | ||||||||

| Name | Party A | Party B | Party C | Party D | Other parties | Year | ||

| Quadripartite Initiative — QUAD | France | Cyprus | Greece | Italy | – | 2020 | ||

| European Intervention Initiative | France | Belgium | Estonia | Denmark | Finland, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain, UK, Sweden | 2018 | ||

| Central European Defence Cooperation | Austria | Czech Republic | Croatia | Hungary | Slovakia, Slovenia | 2010 | ||

| Lublin Triangle | Lithuania | Ukraine | Poland | – | – | 2020 | ||

| 5+5 Defense Initiative | France | Italy | Spain | Malta | Portugal + Algeria, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco and Tunisia | 2004 | ||

An EU Arms Market Space in the Making?

Demand Side Evidence: Defence Budgets of EU Member-States

Although comparable data reflecting the imprint of the Russian invasion on the defence budgets of the EU27 are not yet available, there is an abundance of information about the upward trend. Reportedly, France will be increasing its multiannual military spending by €118 billion for the period 2024-2030; Germany aims to add a further €10 billion for 2024 in addition to the €100 billion Fund it announced in 2022; Italy’s armed forces will witness a hike of almost €1 billion; Spain will boost its defence expenditure by almost €3 billion for 2023; Sweden and Finland are expected to allocate an additional €1.16 and €1 billion respectively for defence purposes in 2023; Poland will increase its defence expenditures by 1.5% of its GDP for 2023; Estonia’s defence budget will break the of €1 billion threshold, and Lithuania will boost its defence capabilities by more than €500 million. Greece’s defence expenditures will decrease by more than €750 million, but that is after consecutive years in which huge investments were made and sophisticated weaponry procured. There is thus no doubt that the defence budgets of EU member-states are rising as a result of the protracted war, and will most probably continue to do so.

This trend has not been fuelled solely by developments on the Ukrainian front, with governments of EU member-states that are also members of NATO systematically increasing their defence expenditure as a percentage of GDP since 2015. […] On average, the EU’s NATO members have increased their defence expenditure as a percentage of their GDP by 0.5 per cent. Here, Greece, along with Latvia and Lithuania, are the undisputed champions, with a rise in the region of 1.5%, while France, Spain and Portugal have increased their defence expenditure the least, by approximately 0.1%.

However, this trend has not been fuelled solely by developments on the Ukrainian front, with governments of EU member-states that are also members of NATO systematically increasing their defence expenditure as a percentage of GDP since 2015, as illustrated in Figure 5. Following US pressure to bear more of the cost of collective security as well as attending to their own national security concerns, all EU member-states that are members of NATO have been allocating more national resources to defence in the post-financial crisis period. On average, the EU’s NATO members have increased their defence expenditure as a percentage of their GDP by 0.5 per cent. Here, Greece, along with Latvia and Lithuania, are the undisputed champions, with a rise in the region of 1.5%, while France, Spain and Portugal have increased their defence expenditure the least, by approximately 0.1%.

Figure 5: Defence expenditure as a share of GDP, 2014-2022e (based on 2015 prices)

Supply Side Evidence: European Defence Industry and Core Intra-EU Exporters

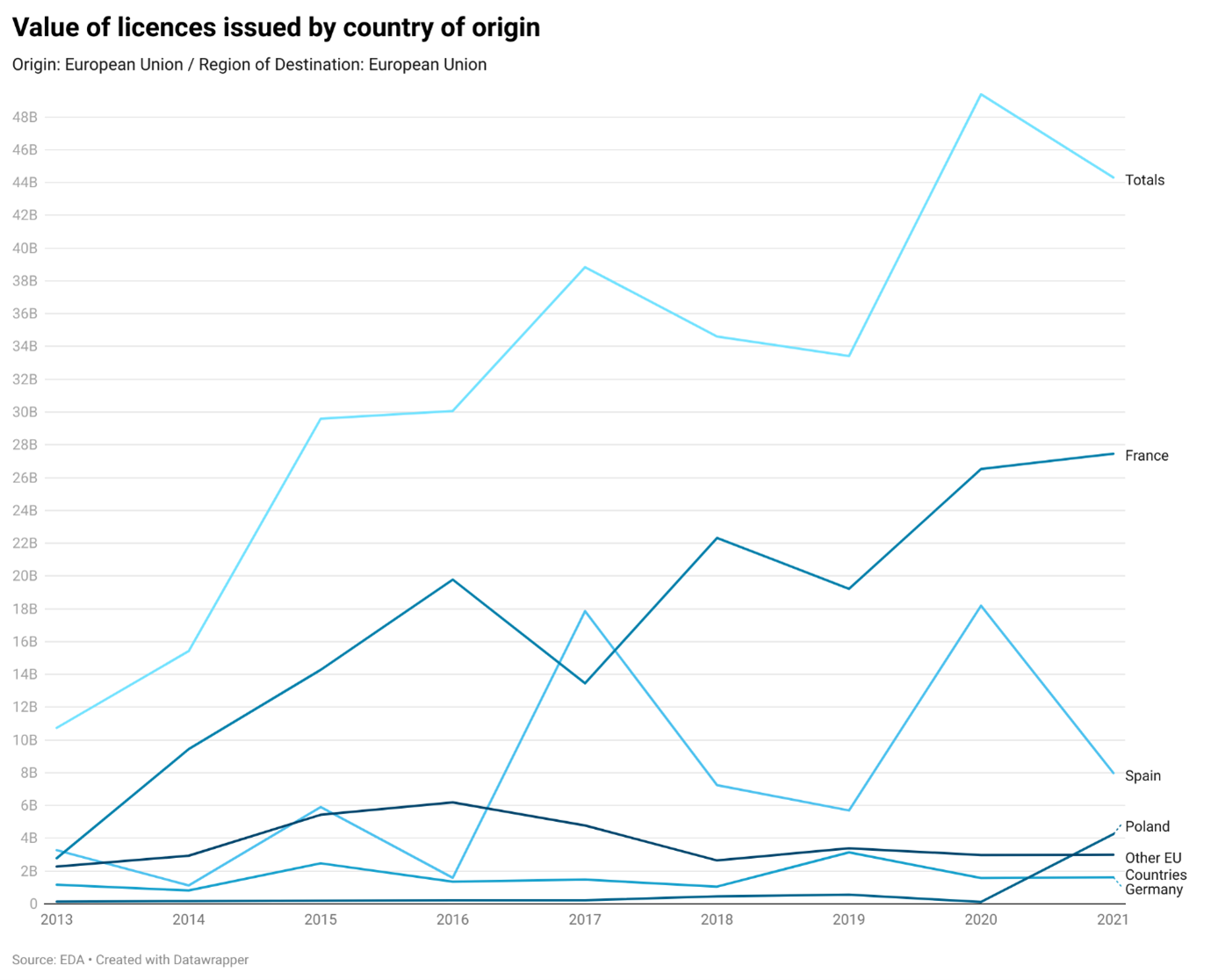

On the supply side, Figures 6 and 7 indicate the number and value of export licences for military equipment issued by all EU member-states. In other words, it provides evidence on the level of military capabilities whose export national authorities have permitted. Export authorisation entails granting a licence to a specific exporter for one or multiple shipments of one or more items, as indicated, for example, in the relevant 2012 EU Regulation on firearms. The real value of exports is more difficult to ascertain.[5] Following a sharp rise in the value of the licences issued in 2013-15, export licences both intra-EU and to the rest of the world have been falling in terms both of numbers and value. Only the value of intra-EU licences have demonstrated steady growth throughout the period.

The number of licences issued by EU member-states fell by almost a third between 2013 and 2021, which indicates a diminishing EU role in the world arms market. This decline owes more to the fall in the number of licences issued to the rest of the world, since the intra-EU decline is less pronounced. In 2021, about two thirds of the licences were issued for the rest of the world and only one third were intra-EU focused, with a minimal rise of just one percent in comparison to 2013.

As indicated in Figure 6, overall, the number of licences issued by EU member-states fell by almost a third between 2013 and 2021, which indicates a diminishing EU role in the world arms market. This decline owes more to the fall in the number of licences issued to the rest of the world, since the intra-EU decline is less pronounced. In 2021, about two thirds of the licences were issued for the rest of the world and only one third were intra-EU focused, with a minimal rise of just one percent in comparison to 2013. Although there have been a couple of years in which intra-EU licenses accounted for over forty per cent of those issued, the main point is that the licence issuing remains heavily imbalanced, with EU member-states adopting an export-oriented rather than intra-EU-focused approach.

Figure 6: Number of licences issued, Total, Yearly Overview

The value of both intra-EU licences and licenses for the rest of the world more than tripled between 2013 and 2021, reaching close to one hundred fifty billion Euros, forty four of which relate to the intra-EU trade.

Moving on to the value of the licences issued, Figure 7 shows that the value of both intra-EU licences and licenses for the rest of the world more than tripled between 2013 and 2021, reaching close to one hundred fifty billion Euros, forty four of which relate to the intra-EU trade. As mentioned above, the value of intra-EU licences has grown steadily over the period. Bringing these insights together with the number of licences, it can be seen that EU member-states issue fewer but more expensive export licences, suggesting a greater emphasis on more sophisticated and higher-value armaments. There was a sudden peak in the first two years of the period under investigation, from 2013 to 2015, with a rise of ninety per cent in 2014 alone. These were the years of the 2014 NATO Declaration and the Crimean imbroglio, and it was these exogenous factors that triggered such an impressive increase.

Figure 7: Value of licences issued, Total, Yearly Overview, in Millions €

Germany is the EU member-state with the highest number of licences issued, although this number is in slight decline, but France has the largest share in terms of value. In terms of value, over sixty per cent of intra-EU licences originate from France.

Zooming in on the European market and looking at the intra-EU situation more closely, Figures 8 and 9 illustrate the defence market interactions between EU member-states. Germany is the EU member-state with the highest number of licences issued, although this number is in slight decline, but France has the largest share in terms of value. In terms of value, over sixty per cent of intra-EU licences originate from France.

Figure 8: Number of licences issued by country of origin

Figure 9: Value of licences issued by country of origin.

From the ‘Producers’ to the ‘Consumers’

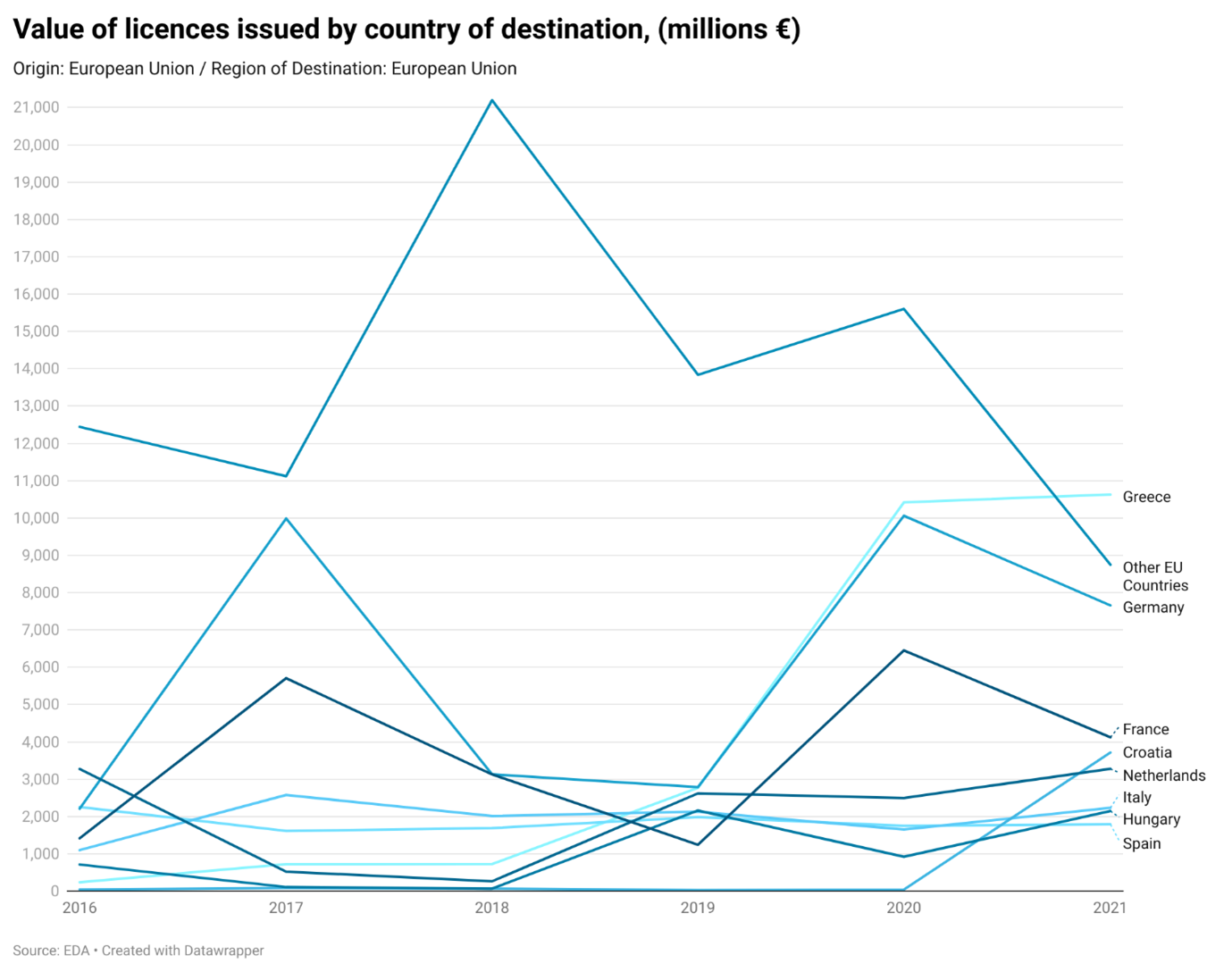

In terms of the value of licenses, Greece is the undisputed champion, more than tripling the amount it spent on armaments procurement from 2019 to 2020 and maintaining these high levels into 2021, too.

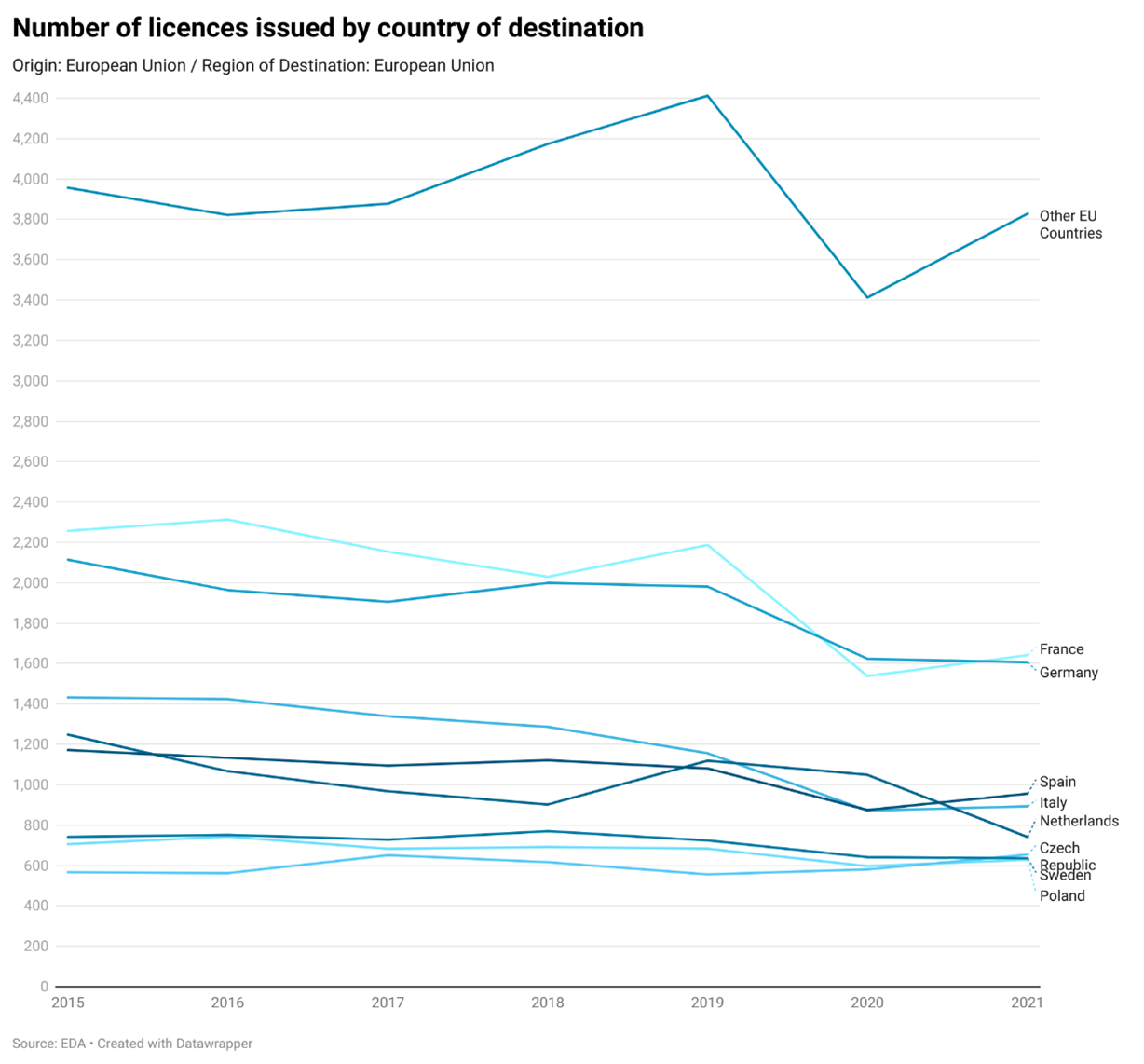

Moving on to the ‘consumers’ of these licences, France and Germany contribute a good deal to the size of the emerging EU marketspace in terms of licences issued, though the number of licenses is in decline. Indeed, the EU member-states for which licences are issued in large numbers feature the same downwards trend (Figure 10). This is in line with the earlier finding about the decrease in the overall number of licences issued by EU member-states for exports destined for other EU countries. In terms of the value of licenses, Greece is the undisputed champion, more than tripling the amount it spent on armaments procurement from 2019 to 2020 and maintaining these high levels into 2021, too. Germany follows Greece in terms of value, despite a small drop in 2021; whether the significant boost in German defence expenditure will be directed intra-EU or elsewhere is an interesting question. Croatia also features a sharp increase, with a spending spree in 2021. For its part, France reveals significant fluctuations from year to year (Figure 11).

Figure 10: Number of licences issued by country of destination.

Figure 11: Value of licences issued by country of destination, Millions €

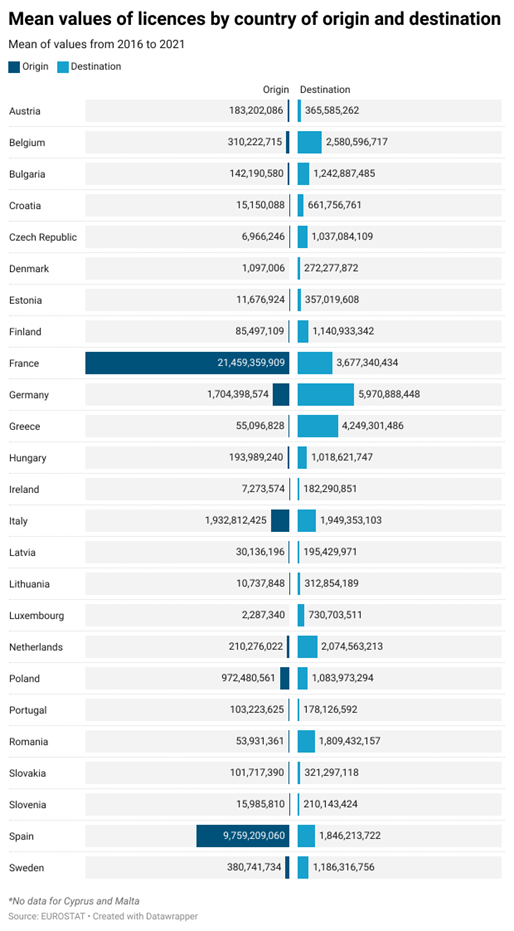

France and to a lesser extent Spain are the two countries which have benefitted most from the emergence of an EU defence market, with both running an impressive trade surplus of almost eighteen and eight billion Euros respectively. Greece and to a lesser extent Belgium, Romania and the Netherlands appear in the list due mainly to their procurement of EU-produced weaponry rather than the exporting activity of their defence industries. Italy and Poland are more balanced.

Figure 12 illustrates the five-year average (2016-21) of EU member-states’ arms trade balance. A cluster of four countries that includes France, Germany, Greece and Spain is the most active in the EU defence market in terms of the total value of exchanges. France and to a lesser extent Spain are the two countries which have benefitted most from the emergence of an EU defence market, with both running an impressive trade surplus of almost eighteen and eight billion Euros respectively. Greece and to a lesser extent Belgium, Romania and the Netherlands appear in the list due mainly to their procurement of EU-produced weaponry rather than the exporting activity of their defence industries. Italy and Poland are more balanced.

Figure 12: Trade balance between EU member-states: 5-Year Average (2016-21), Millions €

Conclusions

An ongoing supranationalization of defence cooperation is slowly taking place, with the Commission pressing ahead and supporting financially closer collaboration between the defence industries of EU member-states through EDF. In the absence of far-reaching industrial cooperation schemes outside the EU framework, the economic considerations of intra-EU defence collaboration weigh ever more heavily on the mindset of many national governments.

France emerges as the undisputed leader in EU defence collaboration, both within the EU institutional framework (PESCO and EDF alike) and in terms of bilateral and plurilateral schemes outside it. Followed closely by Italy, Spain, Germany and Greece, these five member-states form the vanguard group which could constitute the inner core of any future EU defence integration venture. Fuelled by growing security concerns and the concomitant window of opportunity, an ongoing supranationalization of defence cooperation is slowly taking place, with the Commission pressing ahead and supporting financially closer collaboration between the defence industries of EU member-states through EDF. In the absence of far-reaching industrial cooperation schemes outside the EU framework, the economic considerations of intra-EU defence collaboration weigh ever more heavily on the mindset of many national governments.

These considerations are further reinforced by the ongoing increase over the last decade of EU member-states’ defence expenditure as a percentage of their GDP. Despite the sluggish growth of the European economy in recent years, defence remains a priority for all member-states, but obviously a still higher priority for the governments of states facing imminent security threats in Eastern Europe and the Southeast Mediterranean. All EU member-states have increased their defence budgets, to varying degrees.

The European defence industry is shrinking in terms of the number of licences issued, but thriving in terms of their value.

The European defence industry is shrinking in terms of the number of licences issued, but thriving in terms of their value. The former is particularly evident in terms of licences issued for the rest of the world, and indicative of the greater international competition EU countries are facing in the arms trade. However, while the number of licenses has halved, the value of the licences almost tripled between 2013 and 2021. France, Germany, Italy and Spain issue the lion’s share of licences issued with an EU destination, although the numbers for the first two are falling steeply. In terms of license value, France, Germany, Poland and Spain dominate the field, with France alone accounting for sixty four percent (64%) of the overall value of licences issued in 2021. Together, these four countries account for more than ninety-three per cent (93%) of the overall value of licences issued with an EU destination. In terms of licences with an intra-EU destination, Germany, Greece and France top the list of ‘consumers’ viewed as a five-year average (2016-21).

The mapping of the EU defence market reinstates the primary role of the same five member-states that comprise the vanguard of EU defence collaboration: France, Germany, Italy, Spain and Greece.

Bibliography

Alexis, A. (2022). European Defence Fund Beneficiaries: Preliminary lessons learned and open questions. Paris: Institut de recherche stratégique de l’École militaire.

Andersson, J. J. (2015). European defence collaboration: Back to the future. Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies.

Andersson, J. J. (2023). European Defence Partnerships. Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies.

Asseburg, M., & Kempin, R. (2009). The EU as a Strategic Actor in the Realm of Security and Defence? Berlin: Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik.

Bessems, R. (2021). Moving outside the Box: Military Mobility as the Key to Enabling European Security & Defense. Atlantisch Perspectief, 45(4), 28-32.

Blockmans, S. (2018). The EU’s modular approach to defence integration: an inclusive, ambitious and legally binding PESCO? Common Market Law Review, 55, 1785-1826.

Brichet et al. (2021). The Governance of the European Defence Fund. Paris: Fondation Robert Schuman.

Brunnstrom, D. (2008, 12 12). EU aims to up military goals amid DR Congo inaction. Retrieved 3 1, 2023, from OCHA: https://reliefweb.int/report/democratic-republic-congo/eu-aims-military-goals-amid-dr-congo-inaction

Csernatoni, R. (2021). The EU’s Defense Ambitions: Understanding the Emergence of a European Defense Technological and Industrial Complex. Brussels: Carnegie Europe.

Fabry, E., Koenig, N., & Pellerlin-Carlin, T. (2017). Strengthening European defence: who sits at the pesco table, what’s on the menu? Berlin: Jacques Delors Institut.

Harroche, P. (2020). Supranationalism strikes back: a neofunctionalist account of the European Defence Fund. Journal of European Public Policy, 27(6), 853-872.

Hoeffler, C. (2023). Beyond the regulatory state? The European defence fund and national military capacities. Journal of European Public Policy, 1-24.

Håkansson, C. (2021). The European Commission’s new role in EU security and defence cooperation: the case of the European Defence Fund. European Security, 30(4), 589-608.

Kinne, B. J. (2018). Defense Cooperation Agreements and the Emergence of a Global Security Network. International Organization, 72(4), 799-837.

La Moncloa. (2023, 1 19). Sánchez and Macron sign a Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation that strengthens ties between Spain and France. Retrieved 3 1, 2023, from La Moncloa: https://www.lamoncloa.gob.es/lang/en/presidente/news/Paginas/2023/20230119_spanish-french-summit.aspx

Latici, T. (2020). Armament and Transatlantic Relationships – The Romanian Perspective. Paris: ARES.

Lavallée, C. (2011). The European Commission’s Position in the Field of Security and Defence: An Unconventional Actor at a Meeting Point. Perspectives on European Politics and Society, 12(4), 371-389.

Le gleut, R., & Conway-Mouret, H. (2019). Information Report. The President’s Office of the Senate.

Lindstrom, G. (2007). Enter the EU Battlegroups. Paris: European Union Institute for Security Studies.

Martill, B., & Gebhard, C. (2023). Combined differentiation in European defense: tailoring Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) to strategic and political complexity. Contemporary Security Policy, 97-124.

Mauro, F., & Santopinto, F. (2017). Permanent Structured Cooperation: national perspectives and state of play. Brussels: European Parliament, Directorate-General for External Policies, Policy Department.

Meyer, C., Van Osch, T., & Reykers, Y. (2022). The EU Rapid Deployment Capacity: This time, it’s for real? Brussels: European Parliament.

Olsson, P. (2019). National expectations regarding the European Defence Fund: The Swedish Perspective. Paris: Armament Industry European Research Group (Ares Group).

Tardy, T. (2020). France’s military operations in Africa: Between institutional pragmatism and agnosticism. Journal of Strategic Studies, 43(4), 534-559.

Zandee, D. (2018). PESCO implementation: the next challenge. The Hague: Clingendael .

Zandee, D. (2019). Armament and Transatlantic Relationships: The Dutch perspective. Paris: Armament Industry European Research Group (Ares Group).

Zandee, D., & Stoetman, A. (2022). Realising the EU Rapid Deployment Capacity: opportunities and pitfalls. The Hague: Clingendael.

[1] The exact amount is €7.953 billion, of which €5.3 billion are distributed to development actions. The Commission’s initial proposals for a €13 billion EDF were undermined by the economic downturn related to Covid-19 and the overall financial constraints of several member-states, which watered down the ambitions of those with strong military industrial bases in Europe: France, Germany, Italy and Spain (Håkansson, 2021, p. 602).

[2] The first annual work programme, in 2021, allocated €1.2 billion to fifteen categories of action consisting of thirty-seven different topics. The second annual work programme, published in 2022, will allocate €924 million to sixteen categories of action, consisting of thirty-three different topics. The third annual work programme, published in 2023, is structured along 7 calls (4 thematic and 3 dedicated to SMEs and disruptive technologies), consisting of thirty-four different topics, and is expected to allocate €1.2 billion.

[3] The issue of third states’ participation in PESCO has been debated in depth. Proponents of opening up participation, like Germany and Poland, have argued that the EU can take advantage of the advanced technology of other states, while ensuring that the US remains attached to the European defence. On the other hand, some EU member-states are reluctant to invite third states to join, either because this would call into question the efforts being made to achieve European strategic autonomy (like France), or because of existing security concerns (like Cyprus and Greece in the case of Türkiye’s candidacy). Council Decision (CFSP) 2020/1639, published in November 2020, allowed third states that share the EU’s values and principles, provide substantial added value to PESCO projects, and have an active Security of Information Agreement with the EU, to be invited to join following an official invitation made by the participating members of a specific project and a unanimous decision made by the Council (excluding Denmark and Malta). Based on that decision, the US, the UK, Canada and Norway have been authorized to participate in the Military Mobility project, which is extremely important for both the EU and NATO (Bessems, 2021).

[4] In February 2020, the members of the “European Union Training Missions Competence Centre (EU TMCC)” project decided to terminate it.

[5] Arms export data is based on licences granted rather than on actualised exports. This is because data on actualised exports is not typically gathered or available, since it falls within the scope of trade secrecy. Each year, EU member-states submit national reports with data on the arms trade to the EU Council Working Party on Conventional Arms Exports (COARM). While all countries submit data about licenses, not all report a value for their exports. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) also maintains a valuable database on arms exports which, accumulated using a different methodology, mostly covers deals relating to “large” weapons.