Since 2018 the greatest problem around the East Med has been the escalation of disputes Turkey is having with almost all its neighbours regarding delineation of Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) and, seemingly, exploitation of natural resources.

The disputes climaxed during August and September with the Greek and Turkish navies confronting each other and the two countries getting close to the brink of war. Following mediation by Germany, Greece and Turkey agreed to de-escalate confrontation and restart discussions to solve their differences.

The paper reviews the state of the gas industry and its impact on the activities of International Oil Companies (IOCs) operating in the East Med, Turkeys recent gas find in the Black Sea, assesses how these factors may be contributing to these disputes and the underlying reasons behind the disputes, examines agreements reached so far regarding EEZ delineation around the East Med, considers the factors that may affect negotiations, and impact on Cyprus, and makes appropriate recommendations.

You may read the full Policy Brief by Dr. Charles Ellinas, Senior Fellow, Global Energy Center, Atlantic Council, in pdf here.

Introduction

“Since 2018 the greatest problem around the East Med has been the escalation of disputes Turkey is having with almost all its neighbours.”

Since 2018 the greatest problem around the East Med has been the escalation of disputes Turkey is having with almost all its neighbours.

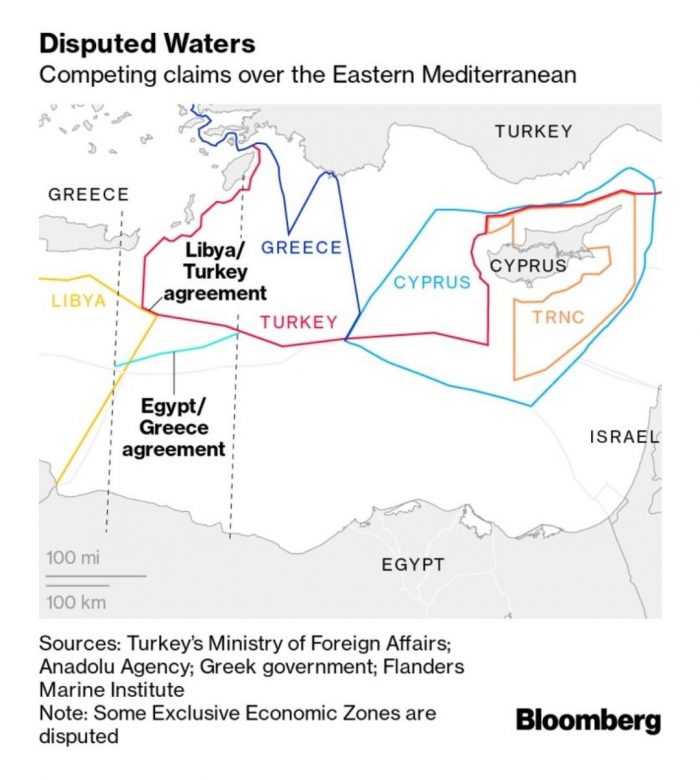

The EEZ and continental shelf claims and counter-claims in the region are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1: EEZ claims

“Turkey has created its own unique rules to justify its claims, not in compliance with UNCLOS and international customary law that recognize the right of islands to EEZs.”

Application of UNCLOS, the UN law of the seas, with full rights for islands would lead to the EEZ boundaries in Figure 4. The hotchpotch of lines in Figure 1 demonstrates the complexity of the problem. Central to this is Turkey’s assertive foreign policy and its claim that, in effect, islands are not entitled to EEZs, including Cyprus and Crete. In fact, Turkey has created its own unique rules to justify its claims, not in compliance with UNCLOS and international customary law that recognize the right of islands to EEZs.

The disputes climaxed during August and September, with the Greek and Turkish navies confronting each other and the two countries getting close to the brink of war.

However, mediation by Germany, supported by the EU and the US and even NATO, is producing results. Turkey has withdrawn its seismic survey vessel, Oruç Reis, from the disputed area between Crete, Cyprus and the Greek island of Kastellorizo (Figure 2) and both navies have now pulled back.

Figure 2: Greek island Kastellorizo off the Turkish coast

Source: Global Security Review

Both Greek Prime Minister Mitsotakis and Turkish President Erdogan have agreed to initiate discussions, hopefully leading to negotiations.

“None of the EEZ claims in the East Med is clear-cut, with the right completely on one side or the other. Even globally, experience shows that the application of UNCLOS eventually led to agreements through negotiation, compromises and often referral to international courts. The East Med is not any different.”

None of the EEZ claims in the East Med is clear-cut, with the right completely on one side or the other. Even globally, experience shows that the application of UNCLOS eventually led to agreements through negotiation, compromises and often referral to international courts. The East Med is not any different. Earlier this year Greece did accept maritime compromises in order to clinch EEZ agreements with Italy and Egypt.

State of the gas industry

In the meanwhile, East Med gas development and plans have been upended by global energy market challenges[1], exacerbated by the adverse impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the global economy.

“…gas development and plans have been upended by global energy market challenges.”

In terms of exploration and production the East Med is at a standstill due to postponement of activities by the International oil companies (IOCs). The industry is in a state of crisis, due to over-supply of oil and gas and subdued demand in global markets brought about by Covid-19. Based on experience from earlier downturns, it may take two or three years to recover. The impact of this on the East Med is that Covid-19 not only has led to cancellation of drilling for gas but has also affected gas developments in general.

IOCs announced cuts in spending, between 20 percent and 50 percent in 2020, with more to come in 2021. Exploration and production activity is unlikely to return in the East Med for a while, with drilling likely to be delayed longer than 2021.

The gas industry was in trouble due to over-production of gas and LNG, much before Covid-19. The pandemic has made it worse. Competition with renewables is also a factor. Covid-19 and its devastating impact on the global economy and energy demand, and the oil price collapse, brought gas/LNG prices in Europe and Asia to very low levels.

The newly released International Energy Agency (IEA) report on gas states that it will take years for global gas demand to recover, forecasting persistent longer-term overcapacity and oversupply. This means that low prices are likely to persist for the rest of the decade, making it very difficult for expensive East Med gas to secure sales in global markets.

“Europe does not need East Med gas.”

In addition, the EU has adopted its Green Deal and is about to raise the target for carbon emissions cut by 2030 from the current 40 percent to 55 percent in comparison to 1990 levels. Through these, EU energy is expected to become greener, with gas consumption likely to be reduced by 25% percent from 2015 levels by 2030. Europe does not need East Med gas.

When activity returns, the IOCs will be going for large projects, easy to develop, with high returns – East Med does not fit into this. Where this is not the case, eventually they will be looking into divesting assets.

However, the IOCs have a wider and longer-term horizon and, as they sell, part of their business is to maintain proven asset levels through new discoveries, as long as there is a long-term possibility that an asset will one day become exploitable. For example, ENI – a key player in the region – has adopted a long -term price of gas of $5.50/mmbtu. As long as a gas-field can be developed and taken to markets within that price, in its eyes it is exploitable.

Most of the IOCs have not yet factored into their thinking the impact of energy transition on long-term global oil and gas demand. ENI, BP and Shell possibly do, but their biggest gas market in the region is Egypt’s domestic energy market that is growing and pays good prices – so they do not depend on exporting their East Med gas.

The same applies to other IOCs operating in Egypt’s EEZ. They will continue their operations there supplying oil and gas to Egypt’s vast and growing energy market. Chevron will do the same in Israel, but without making any new investments.

“…in other parts of the East Med, the IOCs will bide their time. For the reasons cited above, they will maintain a presence, but are unlikely to resume large scale exploration and production – even post-Covid-19 – until, and if, market conditions recover and justify it.”

But in other parts of the East Med, the IOCs will bide their time. For the reasons cited above, they will maintain a presence, but are unlikely to resume large scale exploration and production – even post-Covid-19 – until, and if, market conditions recover and justify it.

As long as uncertainties exist, be it market-related or geopolitical, most IOCs will not commit to making any substantial investments. This leaves regional markets, which have a promising potential, but even these require resolution of disputes and regional cooperation.

So East Med gas exports will remain a challenge. Egypt’s Idku LNG plant has been unable to export LNG since March due to the prevailing very low prices. But production from existing gas fields, such as Tamar, Leviathan and Zohr, is benefiting the domestic markets of Israel and Egypt, where the future of East Med gas may lie – in domestic and regional markets.

Turkey finds gas in the Black Sea

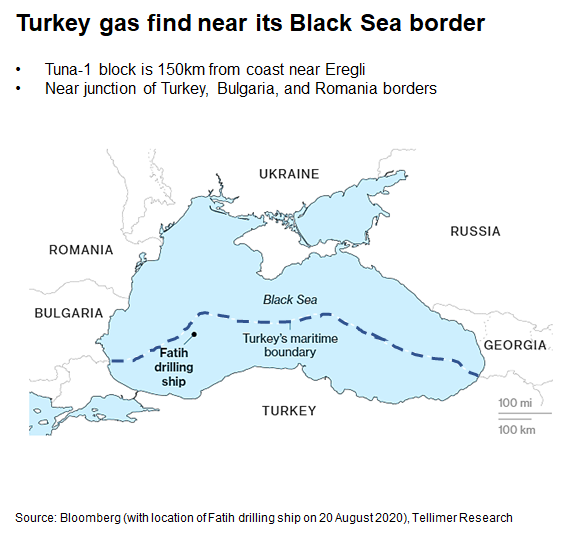

Turkey’s President, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, announced on 21 August a major, 320 billion cubic meters (bcm) lean natural gas find in the country’s EEZ, at the Tuna-1 well in the Black Sea. The gas-field is located about 150km offshore (Figure 3). This is Turkey’s biggest gas discovery ever and the biggest so far in the Black Sea. It was made by Turkey’s national oil company TPAO using the drilling-rig Fatih.

Figure 3: Turkey’s gas discovery in the Black Sea

The exact size of the find and how much of the gas is recoverable will not be known until after more appraisal drilling is carried-out. Nevertheless, it is quite sizeable and when brought on-stream, it could have the potential to produce 10-15bcm/year over the next 15-20 years. With Turkey’s consumption averaging about 50bcm/year over the last three years, Tuna-1 could be providing as much as 20 percent-30 percent of the country’s annual gas demand, easing import-dependence and improving energy security.

“The Black Sea holds more potential for Turkey to make further gas discoveries, rather than the East Med where after drilling seven wells since 2018 – at a substantial cost – no commercial discovery has been made so far.”

The Black Sea holds more potential for Turkey to make further gas discoveries, rather than the East Med where after drilling seven wells since 2018 – at a substantial cost – no commercial discovery has been made so far.

“Turkey’s drilling in the East Med is not directed towards discovering gas, but it is driven by political ends.”

This corroborates the view that Turkey’s drilling in the East Med is not directed towards discovering gas, but it is driven by political ends.

What are they fighting for? Not gas

To all appearances the increasing conflicts in the East Med are all to do with EEZ disputes and control and exploitation of hydrocarbons that, by all indications, the region is blessed with.

Given global developments, especially in the energy sector, are such conflicts justifiable, or is the region stepping back in time? The world, led by Europe, is moving away from fossil fuels and even though transition to clean energy may take time, with the increasing penetration of renewables the world has entered an era of abundance of energy resources, including natural gas.

“East Med gas is likely to continue to be too expensive to exploit commercially in global markets. Thus, the perceived riches locked-in at the bottom of these disputed, and fiercely-contested, seas may never materialize.”

The irony of this whole saga is that with plentiful cheap gas supplies in the global markets expected to continue for a long-time, with prices remaining low, East Med gas is likely to continue to be too expensive to exploit commercially in global markets. Thus the perceived riches locked-in at the bottom of these disputed, and fiercely-contested, seas may never materialize.

In addition, the probability of significant hydrocarbon presence in the area between Cyprus, Kastellorizo, Crete and Egypt’s EEZ boundary – currently the bone of contention between Greece and Turkey – is low.

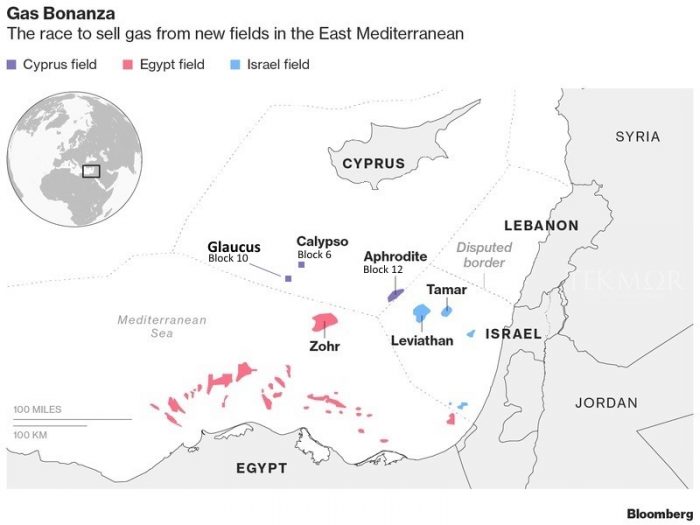

The areas considered to be of higher potential for hydrocarbon discoveries are: Egypt’s entire EEZ, the Levantine Basin that includes parts of Egypt, Israel and Cyprus EEZs – where Tamar, Leviathan and Aphrodite were discovered – the area around the Cyprus/Egypt EEZ boundary – where Zohr, Glaucus and Calypso are – and south-west of Crete (Figure 4). None of these is being contested. The areas claimed by Turkey have mostly low probability of hydrocarbon presence.

Figure 4: East Med’s major gas finds

Source: Bloomberg

“…what are the countries of the region striving for? An unrealistic perception of riches, or plain, well-entrenched, historical rivalries?”

This begs the question: what are the countries of the region striving for? An unrealistic perception of riches, or plain, well-entrenched, historical rivalries? Or is this driven by Turkey’s determination to impose its will and project a regional power image on the wider region stretching from Azerbaijan to Algeria? Whatever it is, natural gas appears to have little to do with it.

It would be very anachronistic if, as a result of the pursue of maritime control of areas of low economic potential – and not for the pursue of hydrocarbons as often claimed – these disputes get out of hand.

What has been agreed up to now

“So far EEZ agreements have been arrived-to through negotiations between the directly involved parties. Unilateral declarations, or declarations ignoring the rights of others, however tenuous these may be, cannot solve the problems and cannot prevail.”

So far EEZ agreements have been arrived-to through negotiations between the directly involved parties. Unilateral declarations, or declarations ignoring the rights of others, however tenuous these may be, cannot solve the problems and cannot prevail.

Formalized EEZ agreements reached so far are between Cyprus-Egypt, Cyprus-Israel, Greece-Italy (Figure 5) and recently Greece-Egypt. All these agreements are based on UNCLOS.

Figure 5: East Med EEZs

Source: GreekCityTimes

Cyprus also reached an agreement with Lebanon, but this has not yet been formalized due to EEZ disagreements between Lebanon and Israel.

Turkey and Libya signed a maritime memorandum in November 2019, which defines a dividing line between the two countries without taking into account at all the rights of the islands, not even Crete. The memorandum was condemned by the EU and the US as “counterproductive and provocative.” However, Turkey used this as the basis of defining its ‘continental shelf’ claim (Figure 1).

Greece is a late-comer to EEZ agreements but has followed a pragmatic approach in its recent EEZ agreements with Italy and Egypt. Both were based on UNCLOS, but with compromises that helped achieve agreement.

The Greece-Italy maritime agreement, signed in June, was based on coordinates agreed in 1977 – before the international implementation of UNCLOS – that appear to limit the influence to islands in the Ionian and deviate from the equidistance principle (Figure 5).

The Greece-Egypt agreement, on August 6, which provoked the wrath of Turkey, has only partially-defined the EEZ boundary between the two countries – about 40 percent – between the 26th and 28th meridians (Figure 1). It does not extend to the Libyan EEZ and to the east it avoids the areas affected by Cyprus and Kastellorizo. This seems to have been done at the request of Egypt, as it considers these issues to be complex, especially in relation to Turkey.

Also, the agreed boundary does not seem to correspond to the equidistant line between Egypt, Crete, Karpathos and Rhodes, but in approximately a 56 percent: 44 percent division in favour of Egypt. But it is a positive first step.

Even though the Greek-Italian and Greek-Egyptian agreements leave ambiguities, they also allow room for future negotiations on the remaining, non-agreed, EEZ boundaries – and perhaps, in the end referral to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at The Hague. However, they are of great importance as a basis for future negotiations. These are realistic agreements, unlike the extreme Turkey-Libya memorandum that completely ignores the rights of islands, even Crete.

Room for negotiations?

Following the frenzy of August and first part of September, Greece and Turkey have been brought back from the brink of naval confrontation. Turkey’s Oruç Reis continued roaming the seas south of Kastellorizo (Figure 6) but has now been withdrawn. Turkey’s aggressive maritime pursuits have not won it any friends have not won it any friends or any international support – quite the contrary. The international community in its entirety is condemning that, with calls for settlement of these disputes through negotiations growing stronger by the day, led by the EU, through Germany, with US, UK and French support – but avoiding stronger action, including sanctions.

Figure 6: Turkey’s seismic survey vessel Oruç Reis, accompanied by Turkish navy frigates

Source: AFP

As the situation has developed, Turkey has not even gained anything tangible through this aggression. Some say that it has reinforced its claims to the contested areas, allowing the country to enter negotiations from a position of strength. But that plainly is not the case. These claims can be addressed only through negotiations, and, as and when these come, everything will be on the table, subject to the levelling-influence of international law.

Greece’s restraint has faced considerable internal criticism but has won Greece strong international support. Through this the risk of naval confrontation has been averted, possibly for the longer-term.

“Discussions between the two countries are due to resume early October.”

Discussions between the two countries are due to resume early October, following de-escalation and German/US mediation. In the event of a deadlock, the likelihood is that these disputes may eventually be referred to international courts, possibly the ICJ, for resolution. This is the sensible way forward, that with EU and US help may prevail.

“Negotiations should take place under strict conditions and within the framework set by international law on the issue of EEZ delineation. Open-ended agendas rarely lead to tangible results.”

The immediate agenda is resolution of maritime disputes. Negotiations should take place under strict conditions and within the framework set by international law on the issue of EEZ delineation. Open-ended agendas rarely lead to tangible results.

Given the compromises Greece accepted in clinching EEZ agreements with Italy and Egypt, there should be scope for negotiation, compromise and agreement with Turkey. By agreeing to restart discussions, it is a hopeful sign that both Greece and Turkey are ready for compromise.

These agreements, and other EEZ agreements around the Mediterranean Sea, provide the ICJ enough precedence and leads to help work out an acceptable compromise, should the two countries eventually refer the case to the court. The problem does not appear to be intractable.

“The only sensible way forward is dialogue.”

The only sensible way forward is dialogue. Let’s hope that through Germany’s continued mediation, and with US support, this will eventually prevail – it provides the main hope for eventual settlement of East Med EEZ disputes.

An additional benefit is that any formula that comes out of such negotiations could also become the blueprint to resolve other East Med regional EEZ disputes.

Negotiating hands

Greece has a strong hand to play:

- It has the internationally-accepted UN law of the seas, UNCLOS, on its side, gaining international political support.

- So far it has handled Turkish provocations and aggression with restraint, without allowing itself to be drawn into conflict.

- The impact of Covid-19 on its economy is being contained, but recovery clearly requires tourism to pick-up.

- It will receive €32billion grants plus as much €40billion as low interest long-term loans from the EU recovery package that can help its recovery.

- It has agreed delineation of EEZs with Italy and Egypt based on UNCLOS, giving it a strong negotiating hand.

- Prime-minister Mitsotakis is enjoying high approval ratings and wants to concentrate on economic recovery.

Turkey’s position is more challenging. Covid-19 is still a threat to its people and its economy, which is suffering badly. As a result, its currency, the lira, is tanking, has declined by about 33 percent against the US dollar since the start of the year. And its agreement with Libya is based on very tenuous grounds, especially if the Prime Minister of Libya’s UN-recognised Government of National Accord (GNA) Fayez al-Sarraj resigns by the end of October, as he announced in mid-September.

In addition, President Erdogan’s popularity has been falling to low levels, amidst the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the country and the dire state of its economy. His party, AKP, is currently polling close to 30 percent in comparison to 42.5 percent during the June 2018 parliamentary elections.

Over the past year Turkey’s currency, the lira, lost about a quarter of its value against the US dollar, having been in freefall throughout his presidency, losing over 70 percent of its value since Erdogan became president in August 2014.

“Clearly both countries have much to benefit by reaching agreement – allowing them to concentrate on recovering from the debilitating effects of Covid-19 on their people and their economies – and much to lose if confrontation worsens.”

Clearly both countries have much to benefit by reaching agreement – allowing them to concentrate on recovering from the debilitating effects of Covid-19 on their people and their economies – and much to lose if confrontation worsens.

Impact on Cyprus

To a certain extent, the potential dialogue between Greece and Turkey and the EEZ boundary agreement between Greece and Egypt side line Cyprus.

The first may lead to an agreement between Greece and Turkey that could eventually impact Cyprus’ EEZ. And yet Cyprus is not party to this dialogue, other than indirectly through its close relationship and coordination with Greece.

This will be even more so if the dispute ends-up being referred to the ICJ, which is quite likely. The court will consider only the issues referred to it, jointly agreed between Greece and Turkey.

The Greece-Egypt agreement only addresses part of the EEZ boundary between the two countries not accounting for Cyprus and Kastellorizo. This was done at the request of Egypt as it considers these issues to be too complicated. This leaves open questions that can be dealt only through negotiations with Turkey – not involving Cyprus.

In the meanwhile, in order to maintain pressure and to convey the message that it is determined to continue with its plans, Turkey continued and escalated intervention in Cyprus’ EEZ. Until early October, it carried on with seismic exploration east of the island, in an area that includes Cyprus’ offshore blocks 2 and 3 licensed to Eni/Total, with Yavuz drilling in block 6. A clear message that Turkey considers Cyprus a completely different issue.

These developments leave Cyprus in a vulnerable situation, with the concern that its position in the resolution of East Med disputes is fast becoming extremely weak, if not impotent. This will be even more difficult if the Greece-Turkey dialogue resumes and progresses. Cyprus then risks becoming isolated.

“The way forward for Cyprus appears to be the resumption of negotiations for the Cyprus problem.”

The way forward for Cyprus appears to be the resumption of negotiations for the Cyprus problem (Cyprob), following ‘presidential’ elections in the north in October. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres has said that after the October elections it is his intention to convene again the five key partners meetings.

“Cyprus must give priority to resolution of its problems delinked from gas – giving priority to negotiations.”

Cyprus must give priority to resolution of its problems delinked from gas – giving priority to negotiations.

In order to facilitate resumption of Cyprob negotiations, Germany has offered to mediate with Turkey to cease drilling and surveying off Cyprus.

With resolution of the Greece-Turkey dispute and Cyprob, Turkey would be in a good position to negotiate a wider, mutually-beneficent, future relationship with the EU.

It could also be better placed to join the newly constituted East Med Gas Forum (EMGF), provided of course that it agrees with its aims. Regional cooperation through EMGF could unlock East Med’s regional energy and gas market potential, bringing economic and commercial benefits to the region that otherwise might not materialize.

Recommendations

“Greece and Turkey can give the lead in rapprochement in the troubled East Med region.”

Greece and Turkey can give the lead in rapprochement in the troubled East Med region. Post-Covid-19 both countries must lift their economies. They can do this only by eliminating conflict through negotiations.

The immediate agenda for the Greece-Turkey resumption of discussions in October should be resolution of maritime disputes. Negotiations should take place under strict conditions and within the framework set by international law on the issue of EEZ delineation. Open-ended agendas rarely lead to tangible results.

Other bilateral issues could be addressed after, and with the confidence of, successful resolution of maritime disputes.

None of the EEZ claims in the East Med is clear-cut, with the right completely on one side or the other. Recent EEZ agreements, and other EEZ agreements around the Mediterranean Sea, involved compromises and provide the ICJ enough precedence and leads to help work out an acceptable compromise, should the two countries agree to refer the case to the court. The problem does not appear to be intractable.

A settlement of the Greece-Turkey maritime dispute could also help Cyprus concentrate on solving Cyprob, decoupled from unrealistic energy aspirations. Following ‘presidential’ elections in the north, all involved parties – Greek and Turkish Cypriots and the three guarantor countries – should heed UN Secretary-General’s call to reconvene the stalled Cyprob negotiations.

Cyprus must give priority to resolution of its problems delinked from gas – giving priority to Cyprob negotiations.

In order to facilitate resumption of Cyprob negotiations, Germany has offered to mediate with Turkey to cease drilling and surveying off Cyprus. This needs to be followed up and Turkey should withdraw from Cyprus’ EEZ.

“For East Med gas the future is local and regional markets.”

For East Med gas the future is local and regional markets. Post-Covid-19, East Med countries should take a more realistic view of their gas prospects by shifting priorities from unrealisable global gas exports to unlocking a regional future.

With solution of the Greece-Turkey dispute and Cyprob, Turkey would be in a good position to negotiate a wider, mutually-beneficent, future relationship with the EU. The EU should send appropriate signals.

It could also be better placed to join the newly constituted EMGF, which could unlock East Med’s regional energy and gas market potential.

[1] https://cyprus-mail.com/2020/09/06/the-future-of-global-gas-demand/