On the occasion of the World Refugee Day, 20th of June, ELIAMEP publishes a Policy Brief on the forthcoming New Pact on Migration and Asylum, by Dr. Angeliki Dimitriadi, Senior Research Fellow and Head of ELIAMEP’s Migration Programme.

COVID-19 has affected access to asylum. Border closures have prevented in many cases asylum seekers from reaching safety, or made them face prolonged delays in their asylum application. The New Pact on Migration and Asylum is expected to be announced by the end of June. It is one of the biggest challenges facing the current European Commission, which is called upon to submit proposals that will be accepted by the Member States with different perspectives but also asylum and immigration needs. The biggest challenge, however, is to ensure that the right and access to asylum is fully preserved and will be a priority for the Union for years to come. In the midst of ongoing conflicts, extreme poverty and increasingly restrictive practices at the external border, it is perhaps the last chance to ground a common migration and asylum policy on the the principles of humanity and solidarity, between Member States and towards asylum seekers.

- The New Pact for Asylum and Migration will seek to bridge the differences between Member States on the solidarity, burden-sharing and common asylum processes.

- Southern member states have tabled a detailed proposal on the way forward grounded on mandatory solidarity.

- Forced movement will continue and likely be exacerbated due to the impact of COVID-19 in critical regions like Africa and Southeast Asia.

You may find the full text in pdf here.

Introduction

According to UNHCR Global Trends report for 2019, 79,5 million people were forcibly displaced. Of those 26 million are refugees, i.e. people forced to flee their country because of conflict, war or persecution. 4,2 million are asylum-seekers, with approximately 2 million new claims submitted world-wide. The scale of global displacement is unprecedented, triggered by multiple factors. Conflict (Syrian Arab Republic, Yemen, South Sudan), extreme violence (Rohingya), and severe socioeconomic and political instability (Venezuela) have resulted in large scale population movements. Climate change is also causing internal displacement as in the case of Mozambique and the Philippines in 2018 and 2019.

“…most refugees continue to be hosted in transit and neighbouring countries.”

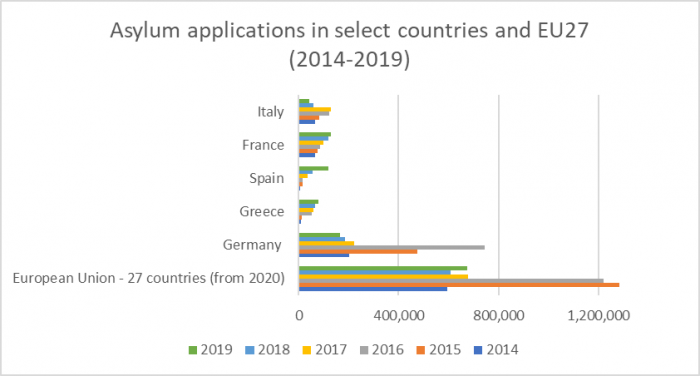

Amidst a “world on the move”, it is time to acknowledge that Europe has largely been left unscathed. At the peak of the European refugee ‘crisis’, 1,216,860 first time asylum applications were submitted across the Member States. That number dropped to 612,685 in 2019. Germany received 142,400 applicants accounting for 23.3 % of all first-time applicants in the EU-27, followed by France, Spain and Greece. In 2020 Syrians and Afghans continue to submit the most applications for asylum, followed by Iraqis, while Eritreans and Syrians maintain high percentages of recognition for international protection. Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Myanmar and the DRC are some of the countries where protracted conflict and displacement remain prevalent. For a Union of 446 million inhabitants, the number of asylum applications remains small. In fact, most refugees continue to be hosted in transit and neighbouring countries.

Yet, deep political divisions emerged in Europe between Member States regarding asylum. It is the reform of the asylum system that will be one of the main challenges of the current European Commission, a reform that has stalled since 2016 due to failure to reach an agreement on the Dublin Regulation.

COVID-19: a gamechanger for asylum & migration in Europe

A Νew Pact on Migration and Asylum is expected for release at the end of June 2020. The Pact was delayed due to COVID-19, which proved a gamechanger for migration in Europe. For migrants it has been both a blessing and a curse.

“The Pact was delayed due to COVID-19, which proved a gamechanger for migration in Europe. For migrants it has been both a blessing and a curse.”

On the one hand forced returns have largely stopped across Europe due to the pandemic. In Spain, a decision was made to release migrants from detention acknowledging that the health risks during COVID-19 made detention untenable. Partial and large-scale releases have also been seen in the Netherlands, and France. Temporary regularisation of migrants with a pending residence application has taken place in Portugal until 1 July 2020, while Italy agreed to regularise thousands of migrant workers to address labour shortages for the agricultural sector.

On the other hand, global resettlement has paused, and countries at the front line undertook increasingly harsher measures to prevent arrival at their borders. Border closures have prevented in many cases asylum seekers from reaching safety, or made them face prolonged delays in their asylum application. Malta & Italy failed to respond to distress calls for Search and Rescue and eventually refused the disembarkation of those rescued by NGO vessels. Both countries cited COVID- 19 as the reason for not assisting. Greece, following the events in Evros, suspended asylum for a month, an unprecedented move for an EU Member State and signatory to the 1951 Convention on Refugees. As anti-immigrant discourse increasingly dominates the debate, NGOs have also come under attack. The country has been accused of land and sea push backs, in many cases documented. Greece recently undertook two legal reforms that tighten further the already impossible deadlines; asylum procedure is more complicated and difficult, and detention is now the norm rather than the exception.

The need to reform the Common European Asylum System (CEAS) and create a robust asylum process in Europe has been clear since 2015. Amidst repeated failures to reach a consensus, the New Pact on Migration and Asylum is meant to function as a ‘restart’ for asylum. The Pact, due likely by the end of June, is now also being called to address the changing landscape brought on by the pandemic.

The upcoming New Pact on Migration and Asylum

What do Member States agree on?

Three crucial areas appear to generate agreement between Member States: strengthening of border control, returns and cooperation with third countries.

Progress has already been made as regards border controls. The European Border and Coast Guard Agency (FRONTEX) revision creates a standing corps of operational staff, who will be part of FRONTEX and deployed by it. The FRONTEX budget increases to €9.4 billion in total in the coming multiannual EU financial framework (2021–2027). The Agency’s role is not as extensive, as originally envisaged, however it is reinforced. FRONTEX will be able to extend its operations to neighbouring EU countries but also beyond. It will also be subject to more oversight particularly as regards the application of the Charter on Fundamental Rights. The boosting of external border controls, following the events at the Greek-Turkish land border of Evros in March 2, 2020, will likely be highlighted even further in the New Pact. The Vice President of the European Commission, Margaritis Schinas, in a recent interview noted that the lessons of Evros are erga omnes, suggesting that they will influence the direction of the New Pact. In parallel, the statement by President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, during her visit to Evros in March 2020, indicated how the front line States are perceived: “ I thank Greece for being our European ασπίδα [English: shield] in these times.”.

“…events in Evros did not take place in vacuum. They were largely the result of the failure of the EU to create a common asylum policy that would be applied by all its Member States. This left the EU open to external pressure, to the cost of front-line States but especially to asylum seekers.”

However, events in Evros did not take place in vacuum. They were largely the result of the failure of the EU to create a common asylum policy that would be applied by all its Member States. This left the EU open to external pressure, to the cost of front-line States but especially to asylum seekers.

Border controls are linked with returns, and this is an element where the Union consistently falls short. In 2017 a renewed Action Plan on Returns was released, highlighting the necessity for creating effective return and readmission programs. This is an area where all Member States agree should be prioritised and will likely be the focus of the New Pact. However, as the cases of the EU-Turkey Statement and the Joint Way Forward for Afghanistan have shown – two deals struct in 2016- the focus on returns is problematic, as it falls short of guaranteeing the rights of returnees. Perhaps more critically, there is little knowledge of the sustainability of those returns, particularly when discussing forced returns. This is acknowledged in part in the proposal submitted by Greece, Cyprus, Italy, Spain, and Malta, with the five requesting incentives and assistance offered for reintegration of returnees.

Greece is currently piloting a return program based on incentives. A voluntary return scheme in collaboration with IOM has been set up on the islands, for those that entered Greece until January 1, 2020. A twenty (20) days period is available for registration. The program has capacity for 5000 returnees. As an incentive, a monetary compensation is offered of 2000Euros, funded by DG Home Affairs. Temporarily halted by COVID-19 and the suspension of flights, once it resumes its results should be monitored to see whether it can be replicated elsewhere. The scheme also indicates that Member States are finally understanding proper incentives need to be offered to individuals and third countries for the establishment of return programs with respect to individual and country needs.

Cooperation with third countries is the third element Member States agree on and likely a major focus of the New Pact. This is highlighted in all the proposals submitted thus far regarding the New Pact. The non-paper by Greece, Cyprus, Italy, Spain, and Malta links success of a renewed CEAS with cooperation with third countries. They identify the Silk route and the Sahel as priority areas and acknowledge that the EU needs to guarantee adequate financial support for the host communities that will receive returnees. Cooperation with third countries extends to creating legal channels of entry to Europe, for those in need of protection. The proposal identifies Libya, Niger and Rwanda as priority countries. The geographical focus reflects the priorities of Italy, Spain and Malta, which raises questions on whether Greece and Cyprus would consider a relevant scheme for countries of immediate interest.

What do Member States disagree on?

Though no official information has been released on the Pact, various documents have been made available offering input on the perspectives proposed for incorporation. Returns and strengthening external borders remain shared priority for most Member States and are high in the Commission’s agenda. Two areas are crucial in achieving consent and they are interlinked: the reform of Dublin and solidarity mechanism.

Reforming Dublin

The Dublin Regulation is a long-contested instrument of the CEAS. Though repeatedly blamed for falling short during the refugee ‘crisis’, it is worth remembering that Dublin was never designed to function as a burden-sharing mechanism. Rather, it has been explicitly designed to allocate the responsibility only to the front-line states that receive irregular arrivals by virtue of their geography. As a mechanism for determining who is responsible for asylum processing, it facilitates the transformation of the front-line States into Europe’s ‘shield’.

Although bold, the previous Commission’s proposal on the Dublin Regulation is no longer up for deliberation. Considering the strenuous objections of the Visegrád Four (V4) and refusal to participate in the relocation mechanism, it is unlikely that a permanent redistribution system will be proposed and if it is, it will likely be watered down to avoid further divisions.

“…accelerated border procedure does not guarantee a fair and effective examination of international protection claims. Secondly, this proposal continues to place extraordinary burden on front line states.”

A non-paper released from Germany’s Interior Ministry suggested that the countries at the external borders should undertake compulsory screening of asylum seekers. The accelerated border procedure would be applied (which is currently in place at the hotspots). Those whose application would be deemed manifestly unfounded or inadmissible would be denied entry and returned to the third country. The shift to accelerated border procedure appears in all proposals submitted, which indicates it will likely be included in the new Pact.

The proposal presents challenges for asylum seekers and frontline states. Firstly, accelerated border procedure does not guarantee a fair and effective examination of international protection claims. Secondly, this proposal continues to place extraordinary burden on front line states. Most concerning is that it assumes returns will take place, when in fact recent experience has shown returns are neither simple nor necessarily achievable. In theory, for a system like this to work, hundreds of trained officers should undertake initial assessment of arrivals, separate those eligible for return and provide reception facilities that are in line with the requirements set in the Return Directive. This in turn, requires financial assistance, operational capacity, but also time.

At opposite ends, CY/EL/ES/IT/MT have tabled a comprehensive proposal that seeks to bridge the divide between the proposals initially endorsed by the European Parliament and those submitted by Member States. The alliance of five proposes a permanent distribution mechanism that acknowledges the links between the asylum seeker and the Member State (for example family reunification, previous visa/residence, academic qualifications). Distribution is to be based on an automated central system that would identify the cases where the criteria do not apply. Exception is provided for those deemed a “danger to security and public order”, who remain the responsibility of the first country of arrival. The proposal transfers the responsibility for screening under the accelerated procedure to the Member State allocating the application. This would effectively render all Member States responsible for their share of asylum processing.

There is a significant gap between the two proposals, with front line States seeking a mandatory mechanism that applies for all, while the German proposal retains key elements of Dublin, particularly as regards border processing responsibility.

“…the Visegrád Four (V4), joined by Estonia, Latvia and Slovenia. In a letter to the European Commission the group expresses strong objection to compulsory relocation in any form.”

Adding to the complexity is the objection raised by the Visegrád Four (V4), joined by Estonia, Latvia and Slovenia. In a letter to the European Commission the group expresses strong objection to compulsory relocation in any form. On the other hand, the V4 agree with the strengthening of the external borders of the EU and appear preliminarily in line with the recent Greek proposal for an emergency clause that allows for ‘elastic reaction’ in the event of a crisis. Though what that reaction would entail remains unknown, the introduction of a lawful manner of derogation from the CEAS is highly problematic.

Flexible solidarity

Solidarity, as a value frame but also a necessity, dominated the refugee ‘crisis’ and remains the crux of the division between Member States.

Germany, France, Spain and Italy’s proposal notes that “resorting to other measures of solidarity than relocation must remain an exception, only for motivated reasons”. The German position, which has received support from the European Commission, is one of flexible solidarity. Already in 2018 German Minister of Interior, Horst Seehofer, noted that flexible solidarity could entail “sending more staff to the borders or giving money for joint border security. We should be more flexible and rely on flexible solidarity.” The call was recently repeated, with flexible solidarity proposed but now made mandatory. In other words, Member States must participate one way or another.

Though it would be a step forward, it still poses a risk for front line states, which will likely be on the receiving end of financial support and assistance in terms of seconded experts but with no-EU wide redistribution on offer. This is particularly crucial in cases of large influx, which has the potential to see diminished places offered by Member States for relocation.

“…the alliance of five proposal restores solidarity to its original form by seeking a mandatory redistribution mechanism […] the principle of solidarity necessarily implies accepting burden-sharing, grounded on the fact that this is a Union of members who share the same values but also responsibilities.”

Recognising this, the alliance of five (CY/EL/ES/IT/MT) proposal restores solidarity to its original form by seeking a mandatory redistribution mechanism. Both Greece and Italy have tested flexible solidarity in the past, with the relocation of unaccompanied minors in the case of the former, and the relocation of those disembarked in the case of Italy. Select Member States participated, and the process has proven difficult and lengthy. In the end, it’s worth remembering that solidarity is a legal obligation in the EU, established in Articles 67(2) and 80 TFUE and this has been noted also by the judgement of the Court of Justice of the EU in the 2017 on the relocation mechanism. It was reinforced in the recent Opinion Of Advocate General Sharpston (31 October 2019) highlighting that the principle of solidarity necessarily implies accepting burden-sharing, grounded on the fact that this is a Union of members who share the same values but also responsibilities.

The way forward

It is expected that a mandatory redistribution mechanism will be incorporated in the Pact. It will likely seek to bridge the different proposals -Germany and Southern Members- with a watered-down redistribution mechanism for those receiving protection incorporating a form of flexible solidarity. It will likely also be linked with further support from FRONTEX and the European Asylum Support Office (EASO). Priority will likely be given to the accelerated border procures, which will increase the level of risk for asylum applicants. It is unlikely the Pact will make significant strides towards boosting access to protection for asylum seekers.

The geographical priorities of the European Commission and Member States will influence the structure of the new Pact.

“Movement of forced migrants, asylum seekers and those seeking economic betterment will continue in the years to come.”

Africa will likely be the geographical focus as it impacts migration to the Mediterranean, but it is also home to 1 billion people. The Joint Communication to The European Parliament and The Council Towards a comprehensive Strategy with Africa already includes cooperation on migration in the field of return and readmission, with the aim to strengthen voluntary returns and conclude EU readmission agreements. However, Southeast Asia must also be considered, as it constitutes a key region of mixed migratory arrivals. In Bangladesh, many factories have been shut down indefinitely due to limited orders because of COVID-19. This will result in an increase in unemployment, and extreme poverty is a key driver for forced migration. Similar challenges emerge across Southeast Asia whether in the garment industry, agricultural sector, or manufacturing. In parallel, conflicts continue, with the latest deteriorating situation in the Sahel region, causing hundreds of people to flee. Remittances to Africa and Asia will reduce, as a result of the economic downturn, impacting millions of families who depend on this direct source of income and functioning as a driver for migration. Movement of forced migrants, asylum seekers and those seeking economic betterment will continue in the years to come. The challenge for the EU is to find a balance that guarantees protection and safety to those in need, while ensuring that those unable to remain are treated in a dignified and humane manner and assisted in their return and reintegration process. It must also reach an agreement that incorporates both solidarity and responsibility sharing among Member States. The pandemic is an added challenge in an already difficult balancing act.

“Compromises are essential but should not jeopardise the right to asylum nor result in a system whereby Member States adopt different forms of solidarity depending on number of arrivals.”

The New Pact on Asylum and Migration is perhaps the last opportunity the European Union to create a holistic and common approach to migration and asylum. Compromises are essential but should not jeopardise the right to asylum nor result in a system whereby Member States adopt different forms of solidarity depending on number of arrivals.

Issues to consider

- The right to asylum must be protected without exception. The New Pact should make it a priority that Member States facilitate rather than restrict access to the asylum procedure and that detention of asylum seekers does not become the norm. Push backs, detention beyond what is prescribed in EU law and emergency measures that go beyond the scope of what CEAS prescribes should be avoided. This is particularly crucial considering the exceptional measures undertaken during COVID-19 in countries like Greece and Hungary. Human Rights are at the heart of the value framework of the EU.

- Flexible solidarity, if incorporated, must incorporate a dimension of redistribution of asylum seekers for all countries. In other words, all Member States must take a percentage of asylum applicants and complement their remaining ‘contribution’ through financial or other means. Failure to achieve this will result in further political divisions as already witnessed in the past five years. It will also increase discontent with the common European project in front line countries that are asked to function as ‘shields’ to irregular migration.

- Member States that refuse to comply with solidarity mechanisms should face penalties. Solidarity is mandatory not optional, and the European Commission must identify ways of enforcing this, by imposing financial or other penalties in areas that are critical to the respective Member States.

- In the scenario where the right to deviate from the rules is introduced, it would need to be limited, proportionate and monitored in an effective manner from the European Commission to ensure human rights and fundamental rights of persons applying for asylum are protected, particularly access to the asylum procedure and fair processing. It should not be up to the Member States to decide but should require a recommendation from the European Commission and a vote from the Council to avoid individual Member State’s assessment. Civil society should also be allowed to weigh in, to provide an independent assessment of the situation on the ground.

- Support to front line countries should not focus only in offering financial assistance and personnel. The external dimension of cooperation must be encouraged and strengthened by assisting Member States in reaching Readmission agreements that offer concrete incentives for cooperation. The aim should be to target countries of origin rather than transit and establish legal pathways to counterbalance return operations.

- Incentives offered to third countries need to move beyond financial assistance in the field of border security and returns. Private sector investment is needed to boost local economies, as are training schemes to allow for the younger population to remain in the countries of origin.

- Legal pathways of entry to the European Union must be incorporated. It is time to discuss an extensive humanitarian visa program as well as legal pathways for economic migrants. Legal migration is safe, orderly and allows for Member States time to prepare. This is particularly relevant in a post COVID-19 world, where migrant workers, irregular migrants and asylum seekers are vulnerable and have limited (or no) access to institutional support.