- Surveys show profound changes in the social attitudes of Kurds in Turkey.

- Younger Kurds are more liberal socially and more flexible politically.

- The years 2015–2016 marked a turning point for Kurdish society and brought different attitudes to light among both impoverished and middle-class Kurds.

- The AKP has been losing Kurdish support because of their alliance with the nationalist MHP and policies perceived as being anti-Kurdish.

- The CHP, while starting very low, has been gaining Kurdish support.

- The CHP’s strategy of reconciliation and talking about crimes committed against the Kurds in the past has been paying off.

- While the “Table of Six” does not offer much in the way of concrete benefits for the Kurds, some parties in the People’s Alliance (e.g. Deva, Gelecek) are more progressive vis-a-vis Kurdish demands.

Read here in pdf the Policy paper by Evangelos Areteos, Research Associate, ELIAMEP Turkey Programme and Ekrem Eddy Güzeldere, Non-Resident Senior Research Fellow, ELIAMEP Turkey Programme.

Introduction

Turkey’s Kurdish population is undergoing profound societal changes characterized primarily by the dynamics of secularization and modernization. The younger generations of Kurds, mainly those born after 1981 (Generation Y) and those born after 1996 (Generation Z), have been emerging as the main recipients, but also the principal drivers, of change in the form of the urbanization and social strengthening of the middle and upper-middle classes in the main urban centers of Turkey’s Southeast.

These dynamics are having a profound impact on the traditional networks of Turkey’s Kurds and their relation to politics. The dominant trends are a gradual disaffection with the AKP among many Kurds, the slow but significant strengthening of the CHP, and a shift in the HDP’s policies toward wider democratization and beyond exclusively Kurdish interests and expectations.

Young Kurdish voters will therefore have a growing influence in future elections. Their preferences can decide elections and whose candidate wins.

Turkey has a young population, but its Kurdish component is even younger. Young Kurdish voters will therefore have a growing influence in future elections. Their preferences can decide elections and whose candidate wins. Surveys have shown that the younger generation is less conservative, more liberal on social issues and more open to voting for parties other than the AKP and HDP, which won around 90% of the Kurdish vote until now.

In what will most likely prove to be a tense and ugly election campaign, the Kurds will have to choose the lesser evil, because neither of the alliances actually offers them much. Even as kingmakers, the Kurds must still be “beggars.”

On a political scene marked since 2018 by two alliances—on the one hand, the AKP-MHP People’s Alliance, on the other, the “Table of Six” (CHP, IYI, Deva, Gelecek, Saadet, Demokrat) or National Alliance, the HDP, representing the Kurdish political movement, has been the kingmaker. Because of the AKP’s alliance with the nationalist MHP and a series of policies regarded as anti-Kurdish, the trend so far has favored the National Alliance, which could win in the 2023 presidential elections by receiving the majority of Kurdish votes. However, with more than three months still to go until the elections, both alliances will be fighting either to win the Kurdish vote or at least to neutralize it by making the Kurds abstain in large numbers. The race has just begun. In what will most likely prove to be a tense and ugly election campaign, the Kurds will have to choose the lesser evil, because neither of the alliances actually offers them much. Even as kingmakers, the Kurds must still be “beggars.”

Kurdish society amidst profound change

While Turkey in general has been urbanizing fast, the Kurds have been keeping up impressively. According to data from KONDA, while 27% of the Kurds still lived in areas with a population of less than 2,000 in 2010, this number had decreased to 6% by 2021. In the same fashion, while 32% of the Kurds were urban-dwellers in 2010, this proportion had increased to 45% by 2021, with the proportion of Kurds resident in metropolitan areas increasing from 40% to 45%. Kurds have also been quick to migrate. Three-fifths of the Kurdish population lives in their own (native) cities, but two-fifths of them now live in metropolitan areas in the country, and particularly in Istanbul. According to KONDA, 7% of the population of Turkey as a whole live in rural areas, 40% in urban areas and 53% in metropolitan areas.

Literacy has also been increasing quickly among Turkey’s Kurdish population. According to the same data, although 20% of the Kurds were illiterate in 2010, this number had fallen to 12% by 2021. Accordingly, the number of children who finished their education after the primary level fell to 21% from 35%, while the percentage of children who graduated from middle school rose from 15% to 19%, the proportion of high school graduates rose from 17% to 27%, and university graduates leapt from 5% to 13%.

The rapid urbanization of the Kurdish populations, along with rising levels of education, mainly among the younger generations, is gradually subverting the power of the traditional structures.

The rapid urbanization of the Kurdish populations, along with rising levels of education, mainly among the younger generations, is gradually subverting the power of the traditional structures, mainly the traditional large families under the patriarchal system as well as the traditional networks and power of the tribes (aşiretler), and the Islamic brotherhoods (tarikatlar).

Kurdish society is thus in a full-fledged transitional period in which secularization and modernization are accelerating and the differences between generations and between social strata with different incomes and statuses now dominate the societal dynamics.

According to a major qualitative research project conducted by the Kurdish academic Yusuf Ekinci into Kurdish secularization and recently published as a book, “Kürt Sekülerleşmesi: Kürt Solu ve Kuşakların Dönüşümü” [Kurdish Secularization: The Kurdish Left and the Transformation of Generations], immensely significant changes are underway among the younger generations of Kurds:

- Compared to older generations, Kurdish young people have, like the rest of the country, become more open to premarital relations, which is a reality Islam does not approve of.

- They have adopted a more liberal position on the consumption of alcohol.

- They get divorced more quickly and more often.

- Fewer girls wear headscarves compared to their mothers’ generation.

- They give their babies names that are less rooted in Islam.

- They have a more liberal perspective on LGBTI+ persons.

- Similarly, with regard to gender, they seem be less accepting of behavioral patterns and perspectives justified by the older generation.

- In addition to secularization and modernization, the Kurdish Left has profoundly influenced young people’s views on religious-traditional teachings and perceptions, especially since the 1990s.

- They are removed from and even opposed to the family’s religiosity and traditional worldview.

- They look at the world from a more rational point of view than their parents.

- They think that religion cannot be the solution to the problems of the Kurdish people.

- Emphasizing gender equality and the freedom to embrace sexual orientations different from those of the traditional gender regime cannot be considered independently of the Kurdish Left/Socialist movement.

The main impact of this secularizing-modernizing dynamic has been to drive a wedge between the younger generations and the AKP, and to oblige the HDP to adopt a more realistic leftist stance and ideology.

The main impact of this secularizing-modernizing dynamic has been to drive a wedge between the younger generations and the AKP, and to oblige the HDP to adopt a more realistic leftist stance and ideology.

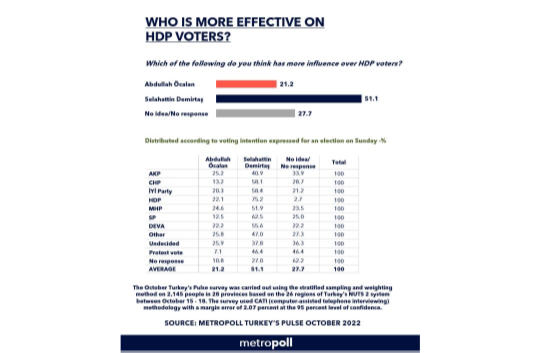

From Evangelos Areteos’ extensive research and field work in Kurdish society, it appears that the younger generations of HDP voters, and especially those from the middle and upper-middle classes, look to Selahattin Demirtaş far more than they do to Abdullah Öcalan. They have also distanced themselves from PKK radicalism.

These observations seem to be corroborated by the recent poll by Metropoll in October 2022, which showed that the perception among the general public, but also among HDP voters, is that Demirtaş has more influence with HDP voters than Öcalan.

Öcalan and the PKK remain very important, as a background and “foundation myth” […] but they have gradually come to be perceived, mainly among the younger generations, as being incapable of facing the challenges and fulfilling the expectations of Kurdish society today.

Öcalan and the PKK remain very important, as a background and “foundation myth”—indeed, as the very symbols of the Kurdish Political Movement and Kurdish identity—but they have gradually come to be perceived, mainly among the younger generations, as being incapable of facing the challenges and fulfilling the expectations of Kurdish society today.

The urban guerilla warfare back in 2015–16, when the PKK attempted to bring the war to the urban centers of the Southeast, provoking a merciless reaction from the Turkish state, has now emerged as a turning point: supported essentially by the lower and impoverished sections of Kurdish society, it caused the middle and upper-middle classes to adopt a very cautious and distant stance.

Τhe strengthening and reshaping of the Kurdish middle classes has become strikingly visible.

Together with the urbanization and secularization/modernization dynamics, the emergence of Kurdish middle and upper-middle classes—mainly in Diyarbakır and other urban centers in the Southeast—is also determining the Kurds’ perceptions of politics and stance towards political parties. Since the de facto end of hostilities between the Turkish state and the PKK in the early 2000s, the strengthening and reshaping of the Kurdish middle classes has become strikingly visible.

This is mainly due to the revival of Kurdish culture, which the state has tolerated as long as it is not directly political, and to the establishment of new urban areas in Diyarbakır where the middle and upper-middle classes could evolve in the context of a thoroughly modern and bourgeois lifestyle, exemplified by housing areas such as Dicle Kent.

Culture has become the main form—in fact, the new “weapon”—of resistance for the Kurds.

Culture has become the main form—in fact, the new “weapon”—of resistance for the Kurds, and it provides the Kurdish middle classes with great opportunities both to produce and “consume” culture, and to keep navigating through identity politics and the ongoing cultural war in Turkey.

Scholars, including Michiel Leezenberg, have coined the term “white Kurds” to describe the emergence of this new upper-middle class in the Southeast, and mainly in Diyarbakır, after 1999. The term is an analogy to “white Turks”, which has been in widespread use since the late 1990s to describe the secular, modern, wealthy Turks of the “establishment” at that time.

According to Leezenberg, a scholar on Islam and philosophy at the University of Amsterdam, “white Kurds” account for approximately 10% of the population of Diyarbakır, and this number is growing. Born, in the main, into the families of rich and conservative landowners and high-ranking state officials in the region, these “white Kurds” have been described by Ömer Tekdemir as “opportunist-pragmatic” Kurds.

The expectations of these Kurdish voters are not “maximalist”, which is to say they do not seek autonomy and do not expect politics to solve all their problems at once.

However, this “pragmatism” would now seem to be expanding among the middle classes, and a new Kurdish voter profile is emerging as a result. The expectations of these Kurdish voters are not “maximalist”, which is to say they do not seek autonomy and do not expect politics to solve all their problems at once. Mostly, they pursue and want realistic politics, and do not act in response to economic motivations alone, or to secure democratic values alone, but also to support and promote their collective identity and its political prerequisites.

The Kurdish vote in the upcoming presidential and parliamentary elections

Until now, Kurdish party politics in Turkey has been a two-party affair, with the HDP (and its predecessors) and the AKP sharing around 90% of the Kurdish electorate over the past decade. However, the pendulum has been swinging in favor of the HDP, as Bekir Ağırdır, a leading pollster from KONDA, describes: “In the 2011 elections, out of 100 Kurdish voters, 52 voted for the AKP and 35 for the independent candidates with whom the HDP participated. In the 2015 elections, this ratio changed: of 100 voters, 65% voted for the HDP and 27% for the AKP.” This also means that, together, the two parties increased their share from 87% to 92%, with all other parties accounting for just 8% of the Kurdish votes cast.

For Turkey-wide party politics and election arithmetic, 2018 was a watershed. [..] Εlectoral alliances of at least two parties became a necessity.

For Turkey-wide party politics and election arithmetic, 2018 was a watershed. With the introduction of the presidential system in 2018, single parties could no longer win the necessary absolute majority on their own; electoral alliances of at least two parties became a necessity.

Τhe two AKP splinter parties DEVA and Gelecek joined the alliance, which has been known as the “Table of Six” ever since.

Two main party blocks have since emerged: On the one hand, in February 2018, the AKP joined forces with the MHP. Later, the small right-wing BBP also joined this so-called People’s Alliance (Cumhur Ittifaki). On the other hand, in May 2018, four opposition parties–the CHP (Kemalist), Good (IYI, urban-secularist-nationalist), Felicity (Saadet, Islamic-conservative) and Demokrat (conservative) parties–agreed to run in the parliamentary elections together as the Nation(al) (Millet) Alliance. In February 2022, the two AKP splinter parties DEVA and Gelecek joined the alliance, which has been known as the “Table of Six” ever since.

The HDP is not part of the opposition alliance. On 20 August 2022, Sinan Ciddi, an associate professor at Marine Corps University, wrote that the “reason for excluding the HDP is relatively simple: alliance members do not want to be tarred with the brush of being perceived as sympathizers of the Kurdish cause in Turkey—a charge which Erdoğan would almost certainly levy against the alliance if they include the HDP as the seventh member.” Instead, the HDP formed an alliance of its own on 25 August 2022 with various small left-wing parties (TİP, EMEP, Emekçi Hareket Partisi, TÖP) for the upcoming elections in 2023; this grouping is called the Labor and Freedom Alliance.

Τhings changed in 2019, when the National Alliance decided to run with joint candidates in the municipal elections. The results were a political earthquake.

In 2018, the government alliance won both the parliamentary and presidential elections with an absolute majority. However, things changed in 2019, when the National Alliance decided to run with joint candidates in the municipal elections. The results were a political earthquake: for the first time since 1994, Turkey’s two main cities—Istanbul and Ankara—were won by CHP mayors. In addition, the CHP-stronghold of Izmir was taken easily, while the CHP also wrested mayorships in big cities like Adana (from the MHP) and Antalya (from the AKP).

The “ugly duckling” that no one wanted to play with had become the kingmaker.

These election victories would not have been possible without the support of the HDP, which in most cities in central and western Turkey chose not to nominate its own candidates and (tacitly) called upon its voters to support the National Alliance candidates. The “ugly duckling” that no one wanted to play with had become the kingmaker. In cities such as Balıkesir where the HDP did not approve the joint candidate and a nationalist IYI-party candidate ran, the AKP won.

This general picture has not changed since and most likely will not change much in the coming months. After 20 years in power, as Berk Esen, Assistant Professor of Political Science at Istanbul’s Sabancı University, wrote in a recent SWP comment: “This will be the first election campaign in which Erdoğan is not the clear favourite.” Together, the two alliances account for more than 80% of the vote. Within the remaining less than 20%, the Kurdish vote is the biggest segment, followed by the conservatives who are disappointed with the AKP. As Mesut Yeğen, an academic expert on the Kurdish issue and until recently CATS fellow, stated in an interview with DW in April 2022: “It’s the math that makes the HDP decisive.”

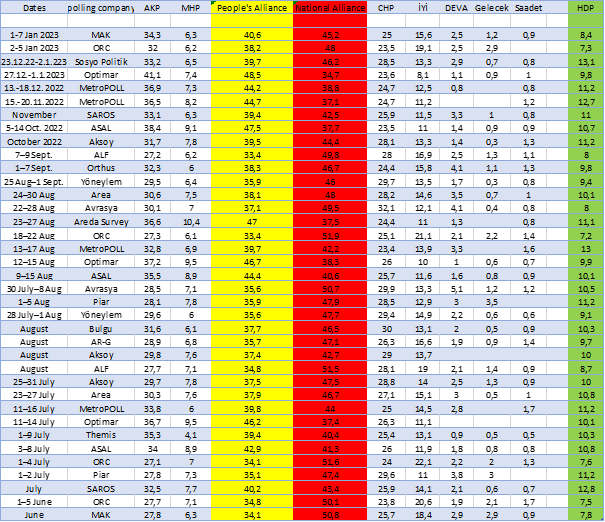

Table 1: Recent election polls[1]

In almost every poll since June 2022, the HDP vote would be the missing link for the People’s Alliance winning an absolute parliamentary majority.

In almost every poll since June 2022, the HDP vote would be the missing link for the People’s Alliance winning an absolute parliamentary majority. As a Euronews study from early January 2023 showed, Kurdish voters would also be decisive in the presidential election. In the first round, 74% would vote for the HDP candidate, if the party nominates its own candidate. Of the rest, 10% would vote for Erdoğan , almost 4% for Kılıçdaroğlu, and 1.4% for İmamoğlu. However, in a second round, 63% said they would vote for the candidate favored by the HDP, while 14% said they would vote for the National Alliance candidate and 11% for the People’s Alliance candidate. Asked more concretely whom they would vote for if Erdoğan stood against Kılıçdaroğlu in the second round, 58.6% said they would vote for Kılıçdaroğlu and 9.3% for Erdoğan, while 24% would not vote for any of them. Should Erdoğan face İmamoğlu, which now seems very unlikely, given the legal investigations against the major of Istanbul, 58.7% would vote for İmamoğlu and 11% for Erdoğan. Both alliances understood the importance of the Kurdish vote, but have implemented different strategies, as Yeğen explains: “The National Alliance is trying to draw Kurdish votes to its side, while the People’s Alliance is trying to neutralize Kurdish votes and neutralize the impact of these votes on the elections.”

Within the National Alliance, the CHP is not only the biggest party, it is also the most active when it comes to the ‘drawing the Kurds to our side’ approach. The institutional leg of this approach was the forming of the so-called “Eastern Desk” (Doğu Masası) roughly a year and a half ago, led by deputy chairman Oğuz Kaan Salıcı and coordinated by Devrim Barış Çelik. The CHP takes pains to stress that the Doğu Masası is not a Kurdish Desk, since it includes all 24 provinces in Turkey’s East and Southeast. For Joseph Sattler, political advisor on Turkey in the German Bundestag, the Doğu Masası “aims to strengthen the party’s presence and organization, especially in the often-neglected provinces of the Southeast, in order to achieve better election results. For example, I was in Van in June 2022. There, the new CHP chairman has a strong local network and had increased the membership significantly.”[2] According to CHP figures, the party could increase membership in the 24 Eastern provinces by between 150 and 300%, though of course this would often be from a very low starting point.

The most important (emotional) ingredient of this strategy since 2020 has been Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu’s approach of reconciliation (helalleşme).

The most important (emotional) ingredient of this strategy since 2020 has been Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu’s approach of reconciliation (helalleşme); although does not relate to the Kurds alone, one of its key strands does concern past injustices against the Kurds. A major step in this direction was his visit to the village of Roboski, where in December 2011, 34 villagers, mostly minors, were killed by Turkish fighter jets while smuggling goods from the Zakho area in Iraqi Kurdistan. In early August 2022, Kılıçdaroğlu told the villagers: “I came here to promise to shed light on this case… There must be justice, the case must be clarified. The dead will not come back… but somehow the pain of their mothers needs to be relieved.”

Another element of Kılıçdaroğlu’s strategy for resolving the Kurdish question relates to the HDP in parliament, at a time when the legal political Kurdish movement is criminalized. Several CHP MPs have met with imprisoned former HDP chairperson Demirtaş, and Kılıçdaroğlu himself met with the current HDP chairs Mithat Sancar and Pervin Buldan in December 2021 at CHP headquarters.

As a more recent step in this direction, on 15 September, Kılıçdaroğlu met Dicle Anter, son of Kurdish author Musa Anter, who was assassinated in 1992.

Kılıçdaroğlu who, having managed to convince well-known personalities formerly active in center-right parties to join the CHP, has strengthened the party’s potential in the region.

Other ingredients of this strategy are regular visits to Kurdish provinces by high-ranking CHP politicians, including Kılıçdaroğlu who, having managed to convince well-known personalities formerly active in center-right parties to join the CHP, has strengthened the party’s potential in the region. Examples of personalities who have joined the CHP include: in July 2021, the former AKP MP from Hakkari, Rüştem Zeydan and in January 2022, Iskender Ertuş, a tribal leader (Ertosi tribe) from Van province. In the past, the tribe declared their allegiance to the DYP, then the BDP, which was banned, and more recently to the AKP. In September 2022, former AKP MP Abdullah Atık was elected chairman of the CHP’s Diyarbakır branch. Atık joined the CHP six months ago. In June 2022, Cengiz Izol of the Izol tribe in Urfa province joined the CHP. Izol was a founding member of the AKP in Urfa, and the chairman of the party organization in its city’s central district.

These measures have resonated positively with Kurdish voters. While, for a long time, the CHP was barely there in the majority Kurdish provinces, today, according to Roj Girasun, general manager of Rawest polling institute, it is “the fastest growing party in the Kurdish provinces.” Girasun explicitly credits Kılıçdaroğlu’s policy of reconciliation as one of the reasons for this. Rawest conducted a poll in June 2022 with over 1,500 respondents in the provinces of Diyarbakır, Mardin, Urfa and Van. Whereas the CHP had scored only 2.7% in 2018, it has reached 9.8% today, almost quadrupling its approval ratings. Girasun assumes that “as a result of these efforts, the CHP may once again succeed, after many years, in securing MPs from Diyarbakır, Urfa or Mardin and in increasing its number of deputies in other provinces such as Kars.”[3]

Turkey has one of the youngest populations in Europe with almost 23% below the age of 15. That is why first-time and young voters are an important factor in election calculations.

Turkey has one of the youngest populations in Europe with almost 23% below the age of 15. That is why first-time and young voters are an important factor in election calculations. TEAM director Ulas Tol argues that “over 10% of voters will be voting for the first time in the 2023 elections. Support for the government among new voters is significantly lower. Among Kurdish voters, the rate of new voters is above the Turkey average and support for the government is even lower. Consequently, among Kurdish voters, young people in general and new voters in particular are important factors in the government’s loss of votes.” According to data from KONDA, the share of first-time voters in Kurdish provinces is significantly higher than the national average: these represent 19% in Şırnak; 18% in Siirt and Hakkari; 17% in Ağrı, Muş and Urfa; 16% in Batman, Bitlis and Van; 15% in Diyarbakır and Mardin; and 14% in Iğdır and Kars.

The secularizing dynamic among young people is clearly emerging as a crucial element in determining the voting preferences of the younger generations of Kurds.

The secularizing dynamic among young people is clearly emerging as a crucial element in determining the voting preferences of the younger generations of Kurds.

According to the findings of a survey conducted by Rawest, “Four out of five of the young Kurds who vote for the AKP stress their identity as a Muslim, while the ratio falls to around 33% for HDP voters. Two thirds of HDP voters emphasize their Kurdish identity, compared with around 33% of AKP voters.”

According to a large-scale survey conducted by TEAM in 2021 on conservative voters, when asked how they perceive the current status of the CHP compared to the 90s, 48% of the respondents answered “worse” and 25% “better”, whereas 35% of Kurdish conservatives answered “better” and 31% “worse”.

This positive trend is also reflected among young Kurdish voters. As the Sosyo Politik Saha Araştırmaları Merkezi showed in a poll from March 2022 in 16 provinces of the Southeast, the CHP would win 9.6%, the AKP 17.5% and the HDP 45.6%. However, among the youngest age group of 18–24 year-olds, the CHP rose to 15.6%, passing the AKP at 14.6%, with the HDP winning 37.7%.

The approval rating of all the parties in the “Table of Six” remains at around 15–18 percent in the Kurdish provinces.

However, having four times more support than before, and greater support among young voters, still does not mean much. The approval rating of all the parties in the “Table of Six” remains at around 15–18 percent in the Kurdish provinces. As Bekir Ağırdır commented: “Kurds are not yet inclined to vote for the CHP […] There is no sign as yet that the opposition or any of the six-party alliance has won the hearts of the Kurds, that they will receive a significant number of votes. They are watching, they are listening, but there is no conviction that they have turned to a new voice, a new face, that they have changed their political preferences.”

While the IYI party is most hostile to accommodating Kurdish language and cultural demands and continues to be categorically against any contact with the HDP, both DEVA and Gelecek have added such issues (e.g. language rights) to their party programs.

The other five parties in the National Alliance are undecided on the Kurdish issue and present a wide range of proposals on how to deal with the issue. While the IYI party is most hostile to accommodating Kurdish language and cultural demands and continues to be categorically against any contact with the HDP, both DEVA and Gelecek have added such issues (e.g. language rights) to their party programs. In a section on the Kurdish issue, the DEVA party program explicitly mentions the “protection, use and development of the mother tongue. It is both the right and the duty of every state to teach its citizens the official language and to enable them to use it. However, democratic states are also obliged to respond to their citizens’ demands for their mother tongue. We believe that the fulfillment of this obligation will both preserve social pluralism and reinforce citizens’ sense of belonging to their country.”

Which is to say that, as a future government, the “Table of Six” would offer the Kurds at least some parties that could be expected to improve the situation vis-a-vis language and cultural rights, with key politicians they could negotiate their demands with.

Ιt will mostly depend on the presidential candidate put forward by the National Alliance. The Kurds would vote for the National Alliance candidate if they were a moderate, but not for an outright Turkish nationalist.

Mathematics make the Kurds the decisive factor, especially in the presidential elections. Since the party positions are relatively clear, it will mostly depend on the presidential candidate put forward by the National Alliance. The Kurds would vote for the National Alliance candidate if they were a moderate, but not for an outright Turkish nationalist. As HDP co-chairperson Mithat Sancar said in June 2022: “If someone intends to bring us today the mentality of the current government, or the mentality that was put into practice in previous periods simply repackaged, we have this to say to them from now: this is not something we can accept.”

However, since early 2023, given both the six-party alliance’s delay in agreeing on a common candidate and the negativity shown, by the IYI party in the main, to any prospect of synchronizing their efforts with the Kurds, the HDP has repeatedly said it will be fielding its own candidate in the upcoming presidential elections.

According to a poll conducted by Spectrum House Düşünce ve Araştırma Merkezi, 70.7% of the voters who say they will support the HDP state that they would prefer to vote for the HDP; 9.4% would prefer the People’s Alliance; and 9.2% the National Alliance. A further 5.2% said they were undecided and 4.2% that they would boycott the elections. According to the same poll, 75.6% of HDP voters think the HDP should nominate its own candidate in the first round of the elections. The preferred candidate is imprisoned former chairman Selahattin Demirtaş, who was proposed by 8.3% of the respondents. This would mean the presidential elections would go to a second round, which many HDP members would now prefer, because it would give the HDP the chance to negotiate with both alliances.

In the current scenario, even though President Erdoğan and the AKP have gained support in recent weeks, thanks both to their international diplomatic efforts and to electoral gifts, such as the sharp increase in the minimum wage to over 8500 TL from about 5500 TL and changes to pension legislation that will allow two million additional people to retire immediately, the National Alliance still seems to be holding all the aces, and only needs to choose its candidate wisely. However, the People’s Alliance will not just sit there over the coming months awaiting its inevitable defeat in the elections. What could the AKP do, in particular, to turn the tide or at least persuade a majority of Kurds not to vote at all?

Mesut Yeğen suggests that the AKP has been revising its policy of completely criminalizing the Kurdish identity, which it largely implemented through until 2019. “Now, Erdoğan is pursuing a far more complex policy on the Kurdish question. His main aim is to prevent HDP votes from influencing the election results.” Yeğen argues that the most important strand in this revised plan is the banning of the HDP, and most likely a parallel ban on roughly 500 HDP politicians and functionaries.

Erdoğan could be banking on the closure of the HDP exposing the Opposition’s disunity on the Kurdish issue, since there clearly will be no common position.

Erdoğan could be banking on the closure of the HDP exposing the Opposition’s disunity on the Kurdish issue, since there clearly will be no common position. The IYI party in particular would rather take a position close to the government’s. But will this be enough to keep HDP voters away from the polls? It looks like a risky gamble, as Roj Girasun explains: “According to one of our polls, 90.2% of HDP voters would do what the party suggests after a ban on the HDP, and only three percent would vote for the AKP.” Taking into account HDP voters’ strong commitment to their party, its closure could turn out to be an own goal for the AKP. With 90% of HDP voters voting for the National Alliance presidential candidate and one party of the National Alliance in the parliamentary elections, this would secure victory for the National Alliance in both elections. Girasun concluded: “That is why I think the AKP has not yet made up its mind, though the MHP really wants closure.”

According to Spectrum House, President Erdoğan has lost almost half of his support among Kurdish voters: only 58.1% of the voters who voted for him in the 2018 presidential elections answered ‘Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’ to the question “Who would you vote for if there was a presidential election this Sunday?”. Among the respondents who previously preferred Erdoğan, 10.8% stated they would prefer the candidate nominated by HDP.

The AKP’s strategy is thus to play on Kurdish voters’ memories of almost a decade ago thus: We did it once, we could do it again.

Of course, the AKP is well aware of this dilemma, and there will be measures in place to convince some of the Kurds that the best place to address Kurdish demands will still be the AKP and president Erdoğan. For several months, the AKP has upped its activity on the ground in the Kurdish provinces. As Yeğen notes: “The AKP wants to convey the message that it is trying to do something different from its current approach to the Kurdish issue. The CHP and the Iyi Parti will not solve this issue; if it will be solved, it will be Erdoğan once again who will do it.” Roj Girasun told Karar TV in June 2022, that even if “there is no sign of Erdoğan trying to find a solution to the Kurdish issue… the AKP still has the advantage as the only party to date which has genuinely tried to pursue a peace process. […] Ultimately, this process has a positive resonance for Kurdish AKP voters as well as HDP voters. This gives the AKP a moral high ground” The AKP’s strategy is thus to play on Kurdish voters’ memories of almost a decade ago thus: We did it once, we could do it again. It was the other side, the PKK, which was responsible for the breakdown of the process, forcing us to ally with the MHP.

Τhe government is also trying to win the hearts and minds once again of at least a portion of the Kurdish electorate.

Additionally, at least on a limited basis, the government is also trying to win the hearts and minds once again of at least a portion of the Kurdish electorate. Thus, even if overall volume still remain very low, the number of pupils taking Kurdish as an elective course has been growing. Two years ago, 8190 pupils chose either Kurmanji or Zazaki as an elective course of two hours per week, but this number grew to 10,063 in the 2021/2022 school year. It is expected that these numbers will have increased again for the current school year.

The government is also trying to confuse Kurdish voters with some good-will steps, such as allowing Selahattin Demirtaş, who has been imprisoned in Edirne since November 2016, to visit his father in Diyarbakır on 12 November 2022, after he had a heart attack and was hospitalized. This could result in some Kurds concluding that, in the end, only the current government will be bold enough to reach out and initiate a reconciliation. Such marks of good will no doubt continue until the elections, raising question marks about the government’s intentions vis-a-vis the Kurds.

It is difficult for the Turkish army to reach the Qandil mountains and face the PKK directly. However, the connection between Qandil and other parts of Northern Iraq can be cut.

Another ingredient are cross-border operations and the fight against the PKK and terrorism. It is difficult for the Turkish army to reach the Qandil mountains and face the PKK directly. However, the connection between Qandil and other parts of Northern Iraq can be cut by reinforcing existing military outposts and building new ones. This can be sold to the public as a success story and as “ending the Kurdish issue,” even if this refers only to the violent, armed aspect of the issue. Nonetheless, it can be presented as stability, tranquility and a precondition for economic growth and prosperity.

In this game of identity politics, there is no longer a place reserved for the Kurds, just as there is no longer a place for liberals or, for example, pro-EU conservatives.

However, the pollsters doubt that initiatives of this sort will work (again). For Bekir Ağırdır, a general problem for the AKP in addressing Kurdish demands is that, following the transformation of the AKP since 2013, “the AKP is no longer a mass party. It has returned to its starting point and became a party of a cultural identity and political tradition. […] Erdoğan’s constituency today is essentially a group that feeds on opposition to the Republic and Western civilization and has issues with secularism and the demand for gender equality.” In this game of identity politics, there is no longer a place reserved for the Kurds, just as there is no longer a place for liberals or, for example, pro-EU conservatives.” Ağırdır is therefore skeptical about the AKP being able to re-emerge as the vehicle for Kurdish aspirations: “Although it is still the second party among the Kurds, the AKP has lost the trust of the majority of Kurds. Therefore, even a hypothetical new solution (peace) process would not be credible.”

This is confirmed by Mehmet Ali Kulat from MAK Research: “Kurdish voters think that the AKP has neglected them in the current government system. It has built roads, hospitals and provided a lot of infrastructure services in the region, but—for example—there are no ministers or effective MPs representing Kurds in the region right now. So Kurds are experiencing a problem of representation.” The infrastructure services are no longer sufficient to compensate for the criminalization of the Kurdish identity.

Roj Girasun also doubts the effectiveness of these measures: “AKP deputies and officials continue to come to the region, President Erdoğan also visited Diyarbakır in 2021, and attempts are being made to repeat the narrative of the solution process, but credibility is now lacking. Also negative for the AKP’s image is the fact that its deputies have little influence. The best-known AKP personalities almost all come directly from the presidential palace. Ibrahim Kalın and Fahrettin Altun are the top names in the AKP, but they are not MPs—they were appointed by the presidential palace.”[4]

Erdoğan is undoubtedly the best campaigner, and he has the most financial and media resources. He will certainly not lie back and plan his retirement. We should be ready for surprises.

After 20 years, six general elections, four municipal elections and three referenda, it seems the AKP’s period as the governing party could run out. One major reason for this is that the AKP lost its Kurdish voters and the Opposition has learned from 12 defeats and is now seen by the Kurds as the lesser evil. If regular elections are held (which is the most likely scenario now), June 2023 is still six months away. Erdoğan is undoubtedly the best campaigner, and he has the most financial and media resources. He will certainly not lie back and plan his retirement. We should be ready for surprises. But if the current polls prove accurate, the Opposition could win. The Kurds will then have to wait and see if they get anything for their support this time round. Because in 2019, they helped the Opposition win the elections without benefiting much from it. Will this also happen after an Opposition victory? Will the Kurds be presented with the same anti-Kurdish policies, simply repackaged? If this were to happen, there would be no alternatives left, a rather frustrating prospect.

Conclusion

Kurdish society, together with Turkish society with which it is deeply interlinked, is experiencing a period of profound change reflected in the political field by the Kurds’ gradual but ever-growing disaffection with the AKP.

The powerful undercurrents of modernization and secularization in both the Kurdish and Turkish elements of society, combined with the AKP’s political choice to ally itself with the MHP, have created a deepening gap between the Kurds and the AKP.

Ulas Tol, a pollster from TEAM, maintains that Kurdish conservatives are defecting from the AKP in significant numbers. The main reasons for this, over and above the AKP’s alliance with the MHP, are the state’s extremely repressive policies vis-a-vis the Kurds and their identity.

The Kurdish identity is the most decisive factor in determining the Kurds’ perceptions and expectations of the parties competing in the Southeast. This identity is continuously being shaped by the ongoing social changes and the Kurds’ gradual alienation from their traditional structures and references.

As the pollster Bekir Ağırdır argues: “Naturally, societal change is accompanied by political change. However, since an old issue like the Kurdish issue is still ongoing, since the demand for identity is salient and dominant, political behavior is carried out through a slightly different process”.

Ağırdır goes on to argue that this identity is “eroding” every class and group, and is thus emerging as the broadest common denominator among the Kurds. Identity politics is emerging once again as a crucial factor in the upcoming elections, and in this context the Kurdish vote will determine the results and hence also Turkey’s future, in relation to the elections, but also after them.

[1] Data taken from the websites or presentations of the polling institutes.

[2] Conversation held on 19 September 2022.

[3] Interview on 18 September 2022.

[4] Interview conducted on 18 September 2022.

References:

Webinar-link:

ELIAMEP-MEDYASCOPE Media Series (ELIMED), “Value-based opposition against authoritarianism?” (Episode 4), 28 June 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lTQ9MNTUshA

Adar, Sinem and Günter Seufert, Turkey’s Presidential System after Two and a Half Years

SWP Research Paper 2021/RP 02, 01.04.2021 https://www.swp-berlin.org/en/publication/turkeys-presidential-system-after-two-and-a-half-years

Ciddi ,Sinan, Turkey’s Erdoğan Is Down But Not Out, 20 August 2022, What does the Opposition coalition stand for beyond defeating Erdoğan? The answer to this is unclear, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/turkey%E2%80%99s-Erdoğan-down-not-out-204307

CNNTürk, Muhalefetteki 4 parti ittifak yapacak, 02.05.2018, https://www.cnnturk.com/turkiye/son-dakika-muhalefetteki-4-parti-ittifak-yapacak

T24, 6’lı masadan 10 maddelik “ilkeler ve hedefler bildirgesi” çıktı, 29 May 2022, https://t24.com.tr/haber/6-li-masa-bugun-toplaniyor-masada-4-gundem-maddesi-var,1037157

Umur, Talu, Davutoğlu anadilde eğitim istedi, Gazete Duvar, 22 August 2020,

https://www.gazeteduvar.com.tr/politika/2020/08/22/Davutoğlu-anadilde-egitim-istedi

Yackley, Ayla Jean, Turkish opposition joins forces for parliament vote, May 2, 2018, https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2018/05/four-turkish-opposition-parties-unite-alliance.html