Once a cradle of empires, civilizations and religions, the Mediterranean region that once dominated world trade today stands among the world regions with the lowest interconnectivity, trade and investment flows. Under these rather unpromising circumstances, the discovery of sizeable natural gas reserves under the seabed of the Eastern Mediterranean in the 2000s and early 2010s appeared as a golden opportunity for the emergence of the Mediterranean in the EU and global energy map, as well as for regional economic cooperation. Yet various missed opportunities and with gas consumption set to decline sharply post 2030 within the European Union, the Eastern Mediterranean natural gas reserves are no longer likely to emerge as gamechanger in EU energy geopolitics. There is another field where the Eastern Mediterranean can play a leading role in the transformation of European energy policy, giving a new dimension to Eastern Mediterranean energy geopolitics. A new, more dynamic and forward-looking energy and climate strategy is needed and with it, a need to evolve from the traditional definition of energy security. The European Green Deal has transformed the discussion on the monetization of natural resources with a negative climate footprint. While the European Union pledges to turn climate neutral by 2050, carbon dioxide emissions must be decisively cut, affecting the use of hydrocarbons including natural gas. This development brings forward a major opportunity for economic cooperation in the Mediterranean, focusing on the development of infrastructure for the production, storage and transport of renewable energy towards Europe. A robust political response is necessary to address climate change to keep our planet viable. The European Green Deal emerges as a new historic cooperation opportunity for a region with lots of regional conflicts as well as with a lot of unrealized potential.

You may read here in pdf the Policy paper by Ioannis N. Grigoriadis, Senior Research Fellow, Head, Turkey Programme, ELIAMEP and Constantinos Levoyannis, Researcher for the project “Winds of Change”, ELIAMEP; Head of EU Affairs at Nel Hydrogen.

Introduction

The Mediterranean has been a cradle of empires, civilizations and religions. It could well be characterized as the world’s first region whose significance has been eloquently outlined in Fernand Braudel’s classical work “The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II”. Wars and epidemics, political and religious conflict could not prevent the circulation of goods and ideas across the sea. The drastic decline of economic and cultural activity in the Mediterranean during the twentieth century has been a rather unfortunate spillover effect of a set of political and economic developments that disconnected the region. It is a big irony indeed that the Mediterranean region that once dominated world trade today stands among the world regions with the lowest interconnectivity, trade and investment flows.

The Hydrocarbon Hope, Hype and Reality

Under these rather unpromising circumstances, the discovery of sizeable natural gas reserves under the seabed of the Eastern Mediterranean in the 2000s and early 2010s appeared as a golden opportunity for the emergence of the Mediterranean in the EU and global energy map, as well as for regional economic cooperation.[1] Early modest discoveries in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of Israel were matched by more considerable findings in the EEZs of Cyprus, Israel and Egypt. The Eastern Mediterranean emerged as a potential hydrocarbon supplier for the European market, at a time when EU authorities sought ways to diversify hydrocarbon imports and improve supply security, particularly in light of souring relations with Russia and the weaponization of natural gas supply in its conflict with Ukraine. Reducing dependency on Russian natural gas imports emerged as a key priority, and Eastern Mediterranean appeared as a good fit. New discoveries in the EEZs of Cyprus, Egypt and Israel, raised hopes that even larger natural gas reserves could be soon discovered, securing the feasibility of monetization projects. The most ambitious one was the EastMed pipeline project, aiming to bring Cypriot, Egyptian and Israeli natural gas to Europe via Greece. Other projects included the construction of a much shorter pipeline to Turkey, for natural gas to be exported to the Turkish market or transported to the European market through the Turkish natural gas grid, the development of a natural gas liquefaction unit in Vassilikos, Cyprus and the transport of the natural gas to the existing liquefaction units in Egypt.

“The civil wars in Libya and Syria and the collapse of the Israel-Palestine peace process transformed the Eastern Mediterranean into one of the world’s most unstable regions.”

The question of whether the emergence of new hydrocarbon reserves in the Eastern Mediterranean (aka “Aphrodite’s gift”) would be fuel for cooperation or fuel for tension has been the subject of much debate for over a decade now. Yet subsequent developments have not met initial expectations, either for the region, the European Union or the hydrocarbons industry. The outbreak of the Arab uprisings in January 2011 did not bring about democratic change on the southern coast of the Eastern Mediterranean. The civil wars in Libya and Syria and the collapse of the Israel-Palestine peace process transformed the Eastern Mediterranean into one of the world’s most unstable regions. On its part, Cyprus failed to become a catalyst. The rise of Nikos Anastasiades and Mustafa Akıncı to the helm of the Republic of Cyprus and the internationally unrecognized “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” in 2013 and 2015, respectively, raised hopes about the possibility of conflict resolution in Cyprus, given the moderate profile of both leaders. In fact, the hydrocarbon bounty was seen as a potential game-changer in peace talks, as it could increase the peace dividend and provide a financial cushion for the high costs of a peace agreement.[2] The monetization of Eastern Mediterranean natural gas reserves through their transport to Europe could bring together the interests of Greece, Turkey and both communities in Cyprus.

“The natural gas bounty ended up further fuelling the outstanding disputes in the region, raising the stakes and triggering escalation.”

Nevertheless, optimism proved once again unfounded. Hydrocarbons turned from a peace to a conflict catalyst. The natural gas bounty ended up further fuelling the outstanding disputes in the region, raising the stakes and triggering escalation. Turkey obstructed the exploration activities licensed by the Republic of Cyprus in its EEZ, and the political risk of the monetization of regional natural gas reserves through the construction of an undersea pipeline to Greece soared. Despite developing regional cooperation ties between Cyprus, Greece, Egypt and Israel, the outstanding security problems in the Eastern Mediterranean remained unresolved. As the Arab uprisings turned into civil wars in Libya, Syria and Yemen, the region was destabilized. Moreover, the failure to reach an agreement in the Crans Montana summit in August 2017 maintained high levels of political risk for major investments in the region. Under these circumstances, the cost of extracting and transporting natural gas through the proposed EastMed pipeline remained at prohibitively high levels for the European natural gas market.[3] The pandemic led to further declines in energy prices, which led all major multinational energy companies to suspend their exploration and monetization projects in the Eastern Mediterranean and beyond. The energy monetization program of the Eastern Mediterranean faced significant challenges.[4] EEZ confrontations eventually proliferated west of Cyprus, towards Crete and the Dodecanese. The signature on 27 November 2019 by Libya’s Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA) and Turkey of a memorandum of understanding (MoU), including the delimitation of the alleged EEZ of the two parties, derailed Greek-Turkish relations. Moreover, Turkey’s decision to conduct in summer 2020 hydrocarbon exploration activities in the Eastern Mediterranean, within an area which Greece considered part of its own EEZ, brought bilateral relations to the lowest point since the late 1990s.

“While the natural gas reserves could have boosted the finances of the states in whose EEZs they were located, the opportunity to turn the Eastern Mediterranean into a significant hydrocarbon exporter to the European market has been most likely missed.”

While the natural gas reserves could have boosted the finances of the states in whose EEZs they were located, the opportunity to turn the Eastern Mediterranean into a significant hydrocarbon exporter to the European market has been most likely missed. Local hydrocarbon reserves will provide crucial help to meet the growing energy needs of coastal states, and a surplus can be liquefied through Egypt’s already existing facilities at Damietta and Idku, so it can be exported as liquefied natural gas (LNG) to the global market, offering a partial solution for the monetization problem.[5] With gas consumption set to decline sharply post 2030 within the European Union, the Eastern Mediterranean natural gas reserves are no longer likely to emerge as a game-changer in EU energy geopolitics. However, there is another field where the Eastern Mediterranean can play a leading role in transforming European energy policy, giving a new dimension to Eastern Mediterranean energy geopolitics.

The European Green Deal

“We are witnessing a paradigm shift in the EU’s energy trilemma of security, sustainability and affordability, with sustainability replacing security at the pinnacle.”

In December 2019, the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, presented the European Green Deal, stating among other that “the old growth model that is based on fossil-fuels and pollution is out of date, and out of touch with our planet.”[6] With 93 percent of the EU population seeing climate change as a serious problem and 72 percent agreeing that reducing fossil fuel imports can increase energy security and benefit the EU financially, it is clear that a business-as-usual scenario is no longer an option. A new, more dynamic and forward-looking energy and climate strategy is necessary, while there is a clear need to evolve from the traditional definition of energy security. We are witnessing a paradigm shift in the EU’s energy trilemma of security, sustainability and affordability, with sustainability replacing security at the pinnacle.[7]

Every year, temperatures continue to rise to record-breaking heights along with sea temperatures and sea levels. On 11 August 2021, in the city of Syracuse, Sicily, l highest temperature ever on the European continent was recorded: 48.8 degrees Celsius. This puts enormous stress not only on natural habitats and biodiversity but also on energy systems. 2021 has seen the spread of wildfires across the Mediterranean, more notably in Italy, Greece and Turkey, where temperatures during the July-August heatwaves surpassed those experienced back in the 1980s. While many of these wildfires were likely provoked by arson attacks or electricity grid accidents, the unprecedented high temperatures and weather conditions greatly contributed to their spreading. These wildfires are set to have lasting and devastating effects on people’s lives and local economies. The heatwaves have also served as a harsh reminder and realization that energy networks in Southeastern Europe and the Mediterranean are in dire need of upgrading, modernization and reinforcement. During the peak of the heatwaves, EU governments in the Mediterranean region warned citizens to pay extra attention to their electricity consumption. In some parts of Greece, electricity supply had to be cut off at times during the day in order to ensure that energy demand would be met. In some cases, surcharges of old overland energy networks struggling to cope with energy demand have been the cause of fires that have spread. There is an urgent need to invest in new energy infrastructure.

“This development brings forward a major opportunity for economic cooperation in the Mediterranean, focusing on the development of infrastructure for the production, storage and transport of renewable energy towards Europe.”

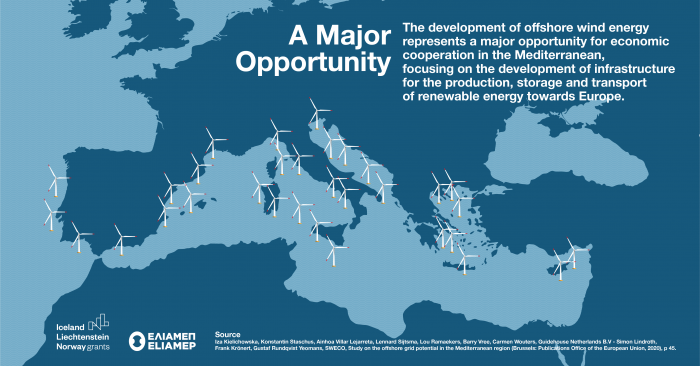

The European Green Deal has transformed the discussion on the monetization of natural resources with a negative climate footprint. While the European Union pledges to turn climate neutral by 2050, carbon dioxide emissions must be decisively cut, affecting the use of hydrocarbons, including natural gas. This means that the European Union would no longer be willing to fund hydrocarbon extraction and transport investments. EU financial support would be crucial for the feasibility of a project of the technical complexity and cost of the EastMed pipeline, but even for smaller projects aiming to develop hydrocarbon monetization in the Eastern Mediterranean. On the other hand, there is a silver lining for the region. This development brings forward a major opportunity for economic cooperation in the Mediterranean, focusing on the development of infrastructure for the production, storage and transport of renewable energy towards Europe.

“What is missing though is the necessary infrastructure, the regulatory framework, as well as the capital for the realization of ambitious renewable energy projects.”

The comparative advantage of the Mediterranean in producing solar and wind energy and its synergies with the growing hydrogen industry are obvious – since the need for more renewables means that there will be more variable and intermittent production of energy that will necessitate zero-emission solutions to provide the energy system with flexibility, among others.[8] What is missing though, is the necessary infrastructure, the regulatory framework, as well as the capital for the realization of ambitious renewable energy projects. These are the fields where the contribution of the European Union could become a game-changer. The Mediterranean natural resources could be crucial for the European Union to meet its climate targets. The European Union, the Mediterranean EU member and non-member states have a rare opportunity to redefine their relations and reform their economies through synergies and cooperation. These points are particularly valid in the Eastern Mediterranean.

“The European Green Deal emerges as a new historic cooperation opportunity for a region with numerous regional conflicts and unrealized potential.”

Interconnectivity can be a valuable target. No country can achieve a successful transition without producing, storing and exporting green energy, without being a part of a new infrastructure, know-how, technology and governance model, which is compatible with the terms of the European Green Deal. A robust political response is necessary to address climate change to keep our planet viable. The European Green Deal emerges as a new historic cooperation opportunity for a region with numerous regional conflicts and unrealized potential.

No agreement or governance arrangement can reach its full potential in promoting economic cooperation and regional interdependence without involving all countries in the Eastern Mediterranean. On the other hand, agreeing on a set of common rules and that international law should be the overarching framework of any partnership is also a sine qua non.

Moving to a European Green Deal-Compatible Energy System

Realizing a European Green Deal-compliant energy system in the Eastern Mediterranean will require a mixture of investment in green- and brown-field projects. Over the past decades, the primary focus of energy and climate policies in Southeastern Europe has been on the transition away from coal and heavy fuel consumption to natural gas as a bridging fuel. A number of significant investments were made, backed by EU funding, notably, the construction and operation of the Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP). In Greece, the government also decided to shut down all lignite plants by 2025, even though lignite has been the country’s primary electricity production fuel. This opens an excellent opportunity for zero-emission and low-carbon solutions in the near future but also considerable challenges in terms of ensuring security of supply and the presence of a robust and coherent regulatory framework to govern the energy system of the future.

With the cost of renewable electricity production dropping significantly, many analysts and scenarios show that renewables will be the most cost-competitive solution from 2030 onwards. However, the question of what to do with existing and newly built gas assets remains high on the policy agenda. To avoid stranded assets, major gas transporters – including TAP – and other industrial players in the region are already looking into low-carbon hydrogen projects as their ticket to decarbonize existing assets. In the gas transportation sector, pipelines can be retrofitted to transport blends of hydrogen and methane in the short to medium term. In the long term, these pipelines can also be fully repurposed to transport pure hydrogen once supply and demand increase.[9] By fitting carbon capture and storage (CCS) units to existing steam methane reformers (SMR) in heavy industrial sites (e.g. refineries, petrochemical plants, steel and aluminium smelters), zero-emitting hydrogen can replace natural gas in production processes. While these projects can contribute to providing greenhouse gas reductions in the short term, the feasibility of CCS in Europe is still yet to be proven at a large scale and deploying CCS with existing SMR units yields an estimated 60-65 percent reduction in greenhouse gas reductions while to this day, the challenge of tracking, tracing and mitigating methane leakage across the entire industrial value chain (production, transport, storage, end use) remains as a major stumbling block for the credibility of the traditional energy sector. Ultimately, safeguarding recent investments and promoting low carbon projects could play an essential role in contributing to decarbonization efforts in the short to medium term. However, the price competitiveness of renewables, the rate at which the cost curve continues to decline, and energy transport costs will be crucial factors in determining the flow of capital and investments in future energy projects as well as the creation of an efficient and well-functioning energy system.

Renewables and Hydrogen

Renewable electrification is already a primary focus of the energy transition in the European Union. The European Commission recently launched its “Fit for 55 Package”, which includes a proposal to review the EU renewable energy directive. As part of this revision, the Commission proposes raising the EU-wide renewable energy target from 32 percent to 40 percent by 2030. Each member state will have to show how it plans on contributing to meeting this objective via its energy and climate plans, which are subject to the scrutiny of the European Commission. In recent years, progress has been made in increasing the share of renewables in the energy mix of Mediterranean states, with Greece hitting its target of 20 percent renewables already in 2020. However, more needs to be done to incentivize further uptake and investment in renewables.

Overall, EU legislation is forcing a rethinking in the business models of all actors across the energy value chain. Many of the relevant national energy companies in Southeastern Europe and the Eastern Mediterranean are traditional energy companies whose portfolios are primarily made up of fossil fuel-related investments and businesses. These companies are already examining how they can diversify portfolios to greener investments that are Green Deal compatible. The transition from a fossil-driven energy company to a green company is possible. The best example of this is in Denmark, where DONG Energy has transitioned from the Danish National Oil and Gas Company into Orsted, which is now the biggest wind energy provider in the world. The transition of such a company can serve as both example and proof that the energy transition is possible, and it makes financial sense for businesses.

“…costs of offshore wind and floating technologies are coming down rapidly, and what was once considered almost unthinkable, is now very much possible.”

In parts of the Eastern Mediterranean, we have seen the development of onshore wind farms. In contrast, for many years, the development of offshore wind parks has been stymied mainly for reasons related to water depths and prohibitive costs of technology. However, costs of offshore wind and floating technologies are coming down rapidly, and what was once considered almost unthinkable is now very much possible. The European Union has also recently presented an Offshore Renewable Strategy and produced research on the offshore grid potential in the Mediterranean,[10] which brings further impetus to the cause. The strategy aims at reaching 300 GW of offshore wind installed capacity by 2050 and 40 GW from ocean energies. Achieving this ambitious target is not purely dependent on the number of wind farms developed. Europe needs to leverage the sweet spots across Europe and install and produce wind power where it is most energy-and-cost efficient. Indeed, the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean have a large untapped potential in this regard and can contribute significantly to achieving the EU 2050 target outlined in the EU offshore renewable strategy. Furthermore, Greece itself has approximately 6,000 islands, islets and rocks, some of which could be ideal locations for the development and production of wind power, as well as for the direct connection of renewable hydrogen projects. In the case of the second, electrolyzers could be connected directly to renewable energy production facilities such as wind farms. Producing hydrogen closer to the source of renewable electricity can contribute significantly to cost reductions. With regards to the water needed for the electrolysis, this can be provided by seawater which can be desalinated on-site.[11] Such projects are already being developed in the North Sea[12] and hydrogen from offshore wind is widely regarded as an emerging market with enormous growth potential. When electricity from offshore wind is not used for direct electrification, hydrogen produced at these sites can be transported to customers via pipeline or ship, or it can be consumed by ships that require refuelling.

“Greece itself has approximately 6,000 islands, islets and rocks, some of which could be ideal locations for the development and production of wind power, as well as for the direct connection of renewable hydrogen projects.”

Spurred by declining costs in renewables, technological progress and EU legislation (e.g., sustainable finance regulation), business leaders in the Mediterranean region, together with investors, need to seize the opportunity and develop new business models that view energy from a more systemic point of view. We can no longer solely rely on traditional energy routes and trading patterns. This is important for several reasons: first of all, the prominent supplier countries in the Gulf are already diversifying their portfolios and preparing for the evolving situation in global energy markets; secondly, the transition to renewable energy means that countries can become more self-sufficient in terms of their energy production and consumption whilst also cutting costs on imports.

To build the energy system of the future, one would need a mix of energy infrastructure solutions. Much of the infrastructure in the Mediterranean is dated, and new investments will be required: on the one hand, to upgrade and retrofit existing infrastructure and, on the other hand, new infrastructure. New electricity cables will need to be laid along with retrofitted[13] and repurposed hydrogen pipelines and even new pipelines to carry hydrogen.

Building the new energy system of the future and producing more renewable energy does not mean that the continent will reach autarky. The European Union will still need imports, and the relationships with its trading partners will need to evolve. We cannot produce enough renewable energy efficiently in Europe to cope with high demand and decarbonize all sectors of the economy. While renewables are set to decarbonize large parts of the economy such as the electricity, heating and road transport sectors, hydrogen is also set to play a crucial role in the so-called hard-to-abate sectors, e.g., steel, aluminium, petrochemicals, heavy-duty transport, including trucks, aviation and shipping. Hydrogen will also have an essential role in managing the variability and seasonal effects of renewable energy, providing flexibility to the energy system. It can also be a cost-effective solution for the transportation of renewable energy across long distances via pipeline since gas transmission grids have a higher transmission capacity than electricity grids.

The Mediterranean as Europe’s major energy and trading hub

“In the years and decades ahead, Euro-Med countries have the ability to develop similar market conditions to those created in Northern Europe over the past decades.”

The EU should continue to position itself as a leader in the energy transition and industrial transformation, and it is in the interests of the EU to remain open to business and global markets. The EU should continue to be at the centre of energy transition and transformation efforts not only in Europe but also in third countries as this will reap benefits not only in terms of energy but also in terms of EU industrial competitiveness. For years, Europe’s energy market has been characterized by the development of liquid trading hubs in Northern Europe, e.g., thirteen percent of Europe’s energy comes through the port of Rotterdam in the Netherlands. In the years and decades ahead, Euro-Med countries have the ability to develop similar market conditions to those created in Northern Europe over the past decades. The Mediterranean is home to several large ports surrounded by heavy industry, including Piraeus, Thessaloniki, Marseille, Genoa, Naples, Barcelona and Valencia. Indeed, the Mediterranean is an essential link between Europe and third countries: we have existing infrastructure and trading relationships with countries such as Morocco, Algeria, Egypt, Turkey and Israel. These countries also have a vast potential to produce renewables at a lower cost than many places in Europe. Indeed, leveraging the EU internal energy market, the countries on the peripheries of the EU Mediterranean borders are well placed to become import hubs for the entry of low-cost renewable energy into the EU market. It is possible to continue EU trade relations with external partners and do it in a manner that is Green Deal compatible.

The EU Hydrogen Strategy refers to the objective of developing 2×40 GW of renewable hydrogen by 2030: 40 GW in Europe and 40 GW in Ukraine and Northern Africa. A roadmap for 40 GW electrolyzer capacity in the EU by 2030 shows a 6 GW captive market (hydrogen production at the demand location) and a 34 GW hydrogen market (hydrogen production near the resource). A roadmap for 40 GW electrolyzer capacity in North Africa and Ukraine by 2030 includes 7.5 GW hydrogen production for the domestic market and a 32.5 GW hydrogen production capacity for export.[14] By realizing 2×40 GW electrolyzer capacity, producing renewable hydrogen, about 82-million-ton CO2 emissions per year could be avoided in the EU[15]. The total investment in electrolyzer capacity is estimated at 25-30 billion Euro, creating 140,000-170,000 jobs in manufacturing and maintenance of 2×40 GW electrolyzers.[16]

Opportunity for the shipping sector

“The subsequent investment decisions shippers make regarding propulsion technologies will lock them into a new cycle lasting another generation.”

One of those hard-to-abate industries is the shipping and maritime sector, where hydrogen and hydrogen-derived fuels such as ammonia show great promise. The International Maritime Organisation (IMO) has called for emissions from shipping to be cut by 50 percent by 2050, and action needs to be taken now. The lifetime of existing fleets is coming to an end, and the Mediterranean is home to some of the most prominent merchant fleets in the world, notably Greek shippers. Future investment decisions are crucial not only for business but for the climate, too. The subsequent investment decisions shippers make regarding propulsion technologies will lock them into a new cycle lasting another generation. The choice is essentially between biofuels, liquefied natural gas and hydrogen. Biofuels have proven politically toxic and environmentally harmful, and many critics point to the lack of resources to produce biofuels without interfering with farm crops and forestry. The use of LNG has also received the same criticism pointed at the gas industry in general, specifically that the use of LNG in new shipping fleets will lead to a lock-in effect to fossil fuels with a negative impact on the climate[17].

The potential for the production of renewable energy and renewable hydrogen in the Eastern Mediterranean, particularly in the Aegean, could lay the foundations for a compelling business case in the region and, more specifically, as it relates to the tourist industry. Hydrogen is already widely regarded as a viable option for short-distance shipping, and this could prove to be appealing in a topography such as the Aegean. If offshore wind farms were to develop together with direct connection hydrogen projects, a large segment of the tourist sector that is the ships transporting holiday-goers from island to island every summer, could be fully decarbonized based on locally produced renewable energy. For smaller boats, liquefied organic hydrogen carrier (LOHC) could also become an option in the near future. Green ammonia derived from hydrogen is also being investigated with great interest and could one day become a globally traded commodity much like oil. When planning new infrastructure investments in the region, this perspective needs to be taken into account. By providing the necessary energy infrastructure and multimodal refuelling infrastructure, it offers a Green Deal-compliant perspective for the tourist, energy, transport and maritime sectors. Besides the pure shipping and maritime angle, with the relevant infrastructure available at ports, trucks, cars and lorries could also be refuelled at ports either by renewable electricity or renewable hydrogen.

Removing Barriers and the Importance of Planning

From a pure ease-of-doing-business perspective, particular attention needs to be put on permitting procedures in the littoral states of the Mediterranean. For example, it can take eight years or more to receive a planning permit for an onshore wind investment in Greece. Systemic problems in Eastern Mediterranean and Southeastern European states related to competition, liberalization of electricity markets persist and need to be resolved to facilitate investment. More broadly, in contrast to other parts of Europe where environmental non-governmental organizations (NGOs) campaign heavily in favour of renewable energy technologies, the environmental movements in the region have been vigorously opposed to renewable installations for reasons related to the impact on the landscape, wildlife, tourism and fisheries – among other. Noise has even been cited as a reason for opposing these projects, even when the large majority of islands, e.g. in the Aegean – are dependent on lone and loud heavy fuel oil generators to meet their basic electricity needs. Early engagement to address local community and local business concerns and misconceptions, as well as NIMBYism regarding renewable energy investments, is paramount for successful projects to be realized. Local communities will need to receive clear and tangible incentives.

“Marine spatial planning should promote a more holistic, multi-use and multipurpose approach, encompassing all relevant sectors, including fisheries, defence, tourism and energy.”

The demand for new renewable energy sites is high, particularly offshore, where there is competition in terms of both space and economic activity. Marine spatial planning is an essential and well-established tool to anticipate change, prevent and mitigate conflicts between policy priorities, and create synergies between economic sectors.[18] To date, EU Member States did not integrate offshore renewable energy strategy into their Marine spatial plans, and this is now a key challenge that needs to be addressed. Member States should align their marine spatial plans as submitted to the European Commission with their respective energy and climate plans. Marine spatial planning should promote a more holistic, multi-use and multipurpose approach, encompassing all relevant sectors, including fisheries, defence, tourism and energy. In this context, projects can also draw on the latest monitoring and digital tools to ensure efficient coexistence and minimizing any detrimental impact on natural habitats.

“The East Med Gas Forum provides an opportunity of regional cooperation that should look beyond hydrocarbons and include renewable energy projects.”

Further research and experimentation should therefore be fostered to further advance multi-use pilot projects and make the multi-use approach more operational and attractive to investors.[19] These actions can be facilitated within regional cooperation fora. There is a plethora of them in the Mediterranean, e.g., the Union for the Mediterranean, which has two relevant energy platforms, one for electricity and one for gas. In addition, the more recently created regional government initiative known as the East Med Gas Forum could widen its scope to look more broadly at energy infrastructure needs in the region, how to exploit synergies and achieve the objectives of the Green Deal. Indeed, the East Med Gas Forum provides an opportunity of regional cooperation that should look beyond hydrocarbons and include renewable energy projects. Addressing the challenge of global warming and desertification in the Eastern Mediterranean requires concerted efforts by all littoral states, regional and global actors.

Concrete action along these lines would signal to business and investors the intentions of regional players regarding the development of renewable energy, thus helping both the private and public sectors to make progress. The countries of Europe’s South and the Mediterranean are set to reap the benefits of EU funding programs linked to European economic recovery. The funds are available. Cooperation and infrastructure connecting the region are needed; they must be rules- and norms-based to be viable and mutually beneficial for all parties concerned.

* Views in this paper represent solely those of the author.

[1] Ioannis N. Grigoriadis, “Energy Discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean: Conflict or Cooperation?”, Middle East Policy, Vol. 21, no. 3 (2014), Simone Tagliapietra, Towards a New Eastern Mediterranean Energy Corridor? Natural Gas Developments between Market Opportunities and Geopolitical Risks [Nota di Lavoro 12.2013] (Milan: Fondazione ENI Enrico Mattei, 2013), pp. 24-27

[2] Grigoriadis, “Energy Discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean: Conflict or Cooperation?”, p. 126

[3] Charles Ellinas, Harry Tzimitras and John Roberts, Hydrocarbon Developments in the Eastern Mediterranean: The Case for Pragmatism (Washington DC: Atlantic Council, 2016), p. 24

[4] Ioannis N. Grigoriadis, “The Eastern Mediterranean as an Emerging Crisis Zone: Greece and Cyprus in a Volatile Regional Environment” in Michaël Tanchum, ed., Eastern Mediterranean in Uncharted Waters: Perspectives on Emerging Geo-Political Realities (Ankara: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) Turkey, 2020)

[5] Simone Tagliapietra, Eastern Mediterranean Gas: What Prospects for the New Decade? (Milan: ISPI (Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale), 2020)

[6] Press Corner, Press Remarks by President Von Der Leyen on the Occasion of the Adoption of the European Green Deal Communication (Brussels: European Commission, 2019)

[7] Constantine Levoyannis, “The EU Green Deal and the Impact on the Future of Gas and Gas Infrastructure in the European Union” in Michalis Mathioulakis, ed., Aspects of the Energy Union: Application and Effects of European Union Energy Policies in Se Europe and Eastern Mediterranean (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave, 2020)

[8] Renewable energy provided by wind and sun are set to make up 60 to 75 percent of the energy mix in 2050. See Eurelectric, Decarbonisation Pathways (Brussels: Union of the Electricity Industry, 2018), European Commission, Energy Roadmap 2050 (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2012).

[9] See for example Media News Center, Corinth Pipeworks Delivers First Hydrogen-Certified Pipeline Project for Snam’s High Pressure Gas Network in Italy (Corinth Pipeworks: Athens & Milan, 2021), available from http://bit.ly/pipeworks [posted on 2/6/2021]

[10] Iza Kielichowska et al., Study on the Offshore Grid Potential in the Mediterranean Region (Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020)

[11] On this, see Hydrogen Europe, Hydrogen Production & Water Consumption: Hydrogen Europe, 2021).

[12] See, for example, the Oyster and the Poshydon projects.

[13] Retrofitting is an upgrade of existing infrastructure that allows the injection of certain amounts of hydrogen into a natural gas stream up to a technically sound threshold of H2/CH4 mixture (i. e. blending). Repurposing implies converting an existing natural gas pipeline into a dedicated hydrogen pipeline.

[14] Ad van Wijk and Jorgo Chatzimarkakis, Green Hydrogen for a European Green Deal: A 2×40 GW Initiative (Brussels: Hydrogen Europe, 2020)

[15] The production of one ton of grey hydrogen emits ten tons of CO2. Each 1 GW of electrolyser capacity produces between 40.000 and 100.000 tons of green hydrogen per year, thus avoiding 400.000 to 1.000.000 tons of CO2 emissions and contributing significantly to the EU climate objectives.

[16] van Wijk and Chatzimarkakis, Green Hydrogen for a European Green Deal: A 2×40 GW Initiative

[17] Bio-LNG has also been discussed but falls under the same criticism as biofuels.

[18] European Commission, An EU Strategy to Harness the Potential of Offshore Renewable Energy for a Climate Neutral Future (Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020), p. 8

[19] Ibid., p. 9

References

Charles Ellinas, Harry Tzimitras and John Roberts, Hydrocarbon Developments in the Eastern Mediterranean: The Case for Pragmatism (Washington DC: Atlantic Council, 2016)

Eurelectric, Decarbonisation Pathways (Brussels: Union of the Electricity Industry, 2018)

European Commission, An EU Strategy to Harness the Potential of Offshore Renewable Energy for a Climate Neutral Future (Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020)

European Commission, Energy Roadmap 2050 (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2012)

Ioannis N. Grigoriadis, “The Eastern Mediterranean as an Emerging Crisis Zone: Greece and Cyprus in a Volatile Regional Environment” in Michaël Tanchum, ed., Eastern Mediterranean in Uncharted Waters: Perspectives on Emerging Geo-Political Realities (Ankara: Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) Turkey, 2020), pp. 38-46

———, “Energy Discoveries in the Eastern Mediterranean: Conflict or Cooperation?”, Middle East Policy, Vol. 21, no. 3 (2014), pp. 124-33

Hydrogen Europe, Hydrogen Production & Water Consumption: Hydrogen Europe, 2021)

Iza Kielichowska, Konstantin Staschus, Ainhoa Villar Lejarreta, Lennard Sijtsma, Lou Ramaekers, Barry Vree, Gustaf Rundqvist Yeomans, Carmen Wouters, Simon Lindroth and Frank Krönert, Study on the Offshore Grid Potential in the Mediterranean Region (Brussels: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020)

Constantine Levoyannis, “The EU Green Deal and the Impact on the Future of Gas and Gas Infrastructure in the European Union” in Michalis Mathioulakis, ed., Aspects of the Energy Union: Application and Effects of European Union Energy Policies in Se Europe and Eastern Mediterranean (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave, 2020), pp. 201-24

Media News Center, Corinth Pipeworks Delivers First Hydrogen-Certified Pipeline Project for Snam’s High Pressure Gas Network in Italy (Corinth Pipeworks: Athens & Milan, 2021), available from http://bit.ly/pipeworks [posted on 2/6/2021]

Press Corner, Press Remarks by President Von Der Leyen on the Occasion of the Adoption of the European Green Deal Communication (Brussels: European Commission, 2019)

Simone Tagliapietra, Eastern Mediterranean Gas: What Prospects for the New Decade? (Milan: ISPI (Istituto per gli Studi di Politica Internazionale), 2020)

———, Towards a New Eastern Mediterranean Energy Corridor? Natural Gas Developments between Market Opportunities and Geopolitical Risks [Nota di Lavoro 12.2013] (Milan: Fondazione ENI Enrico Mattei, 2013)

Ad van Wijk and Jorgo Chatzimarkakis, Green Hydrogen for a European Green Deal: A 2×40 Gw Initiative (Brussels: Hydrogen Europe, 2020)