“I am writing to you on an urgent matter. The competitiveness of European industry is facing a number of challenges.” This is the opening line of the letter sent on January 13th by the Executive Vice-President of the European Commission Margrethe Vestager to the finance ministers of the member states. The letter warned that there was a risk that the Biden presidency’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) could lead some European businesses into moving investments to the US.

The reason is simple: the famous Inflation Reduction Act includes a record $369 billion in spending on climate and energy policies. For example, tax credits are provided to consumers who buy electric cars made in North America. This could automatically make European electric cars less attractive to buyers.

Keeping competition effective is the key pillar of the Single Market since its inception. Thus, state aid control ensures fair competition and is a prerequisite to the well-functioning of the Single Market. In 2019 total state aid spending in the EU was only €135 billion, but in 2020 it increased significantly to €320 billion (2.4% of EU GDP). According to Eurostat data, in Greece the increase in state aid in the first year of the pandemic was also rapid: from 1.1 billion euros in 2019 (0.6% of GDP) to 7 billion euros (4.3% of GDP) in 2020.

The reason for this increase is that state aid rules in the EU had already been loosened long before the announcement of the US green subsidies. On 19 March 2020 the Commission adopted the first provisional framework for state aid measures due to the pandemic (since its adoption, the Temporary Framework has been amended seven times.)

On 23 March 2022, the European Commission also adopted a Temporary Crisis Framework to enable Member States to support the economy in the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. As mentioned in Vestager’s letter, 672 billion euros of state aid have been given so far. In addition, European officials are considering further loosening the rules and redesigning the temporary state aid programs – with simpler rules, broadening the duration and scope, speeding up procedures.

The return of the “European industrial policy” will be difficult for several reasons. First, the EU is competing with the US not only in the scope and the limits of state aid, but also with respect to the length of regulatory processes i.e the time needed for firms to access these subsidies. Currently, the EU is lagging behind on this point due to the complexity of its institutional framework. Second, the relaxation of subsidy restraints will inevitably increase disparities between member states, since governments with more fiscal space will be able to allocate more money to support their industries.

The unequal distribution of state subsidies within the EU puts the foundations of the single market at risk. According to the Commissioner’s letter this is already evident: €356 billion of State aid approved has been notified by Germany (53% of all state subsidies given in the EU in 2022), and another €162 billion to France (24% of the total). Italy was in the third place (51 billion or 8% of all state subsidies in the EU).

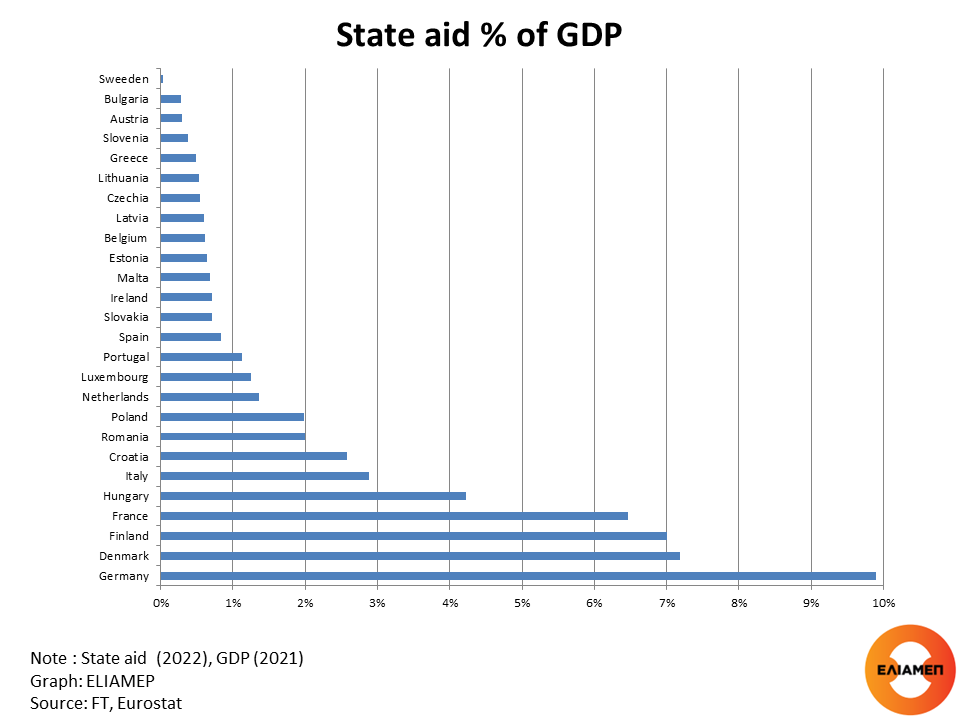

It is of great interest to compare the specific weight of state aid in the national economy of the member states, as shown in the graph. Dividing the amount of state aid in 2022, by countries’ GDP in 2021 (the latest year of available published data), the results show that in Germany state aid was almost 10% of GDP. In Denmark and Finland, the share of state aid in GDP was around 7%. In France it was 6.5%. Beyond that, in Italy it was below 3%, in six other countries between 1% and 2.5%, while in 14 member States state aid corresponded to less than 1% of GDP.

These data point out clearly that there is the risk of fragmentation of the single market with German or French companies (with the support of their governments) becoming dominant. For this reason, there is heated debate on which is the appropriate policy path that the EU should follow. On the one hand, France and Germany call for a relaxation of state aid rules. On the other hand, countries with less fiscal space are concerned with who will provide the funding for state aid, in order to avoid favouring deep-pocket states and lead to distortions that would eventually undermine the Single Market (and make sure that their own industries are not left behind).

In order for state aid policy not to be a “Franco-German deal”, one solution would be to set up a collective European fund to support countries fairly. The president of the Commission has stated that she supports the creation of a European Sovereignty Fund to support the European Industry. Of course, such a “European solution” would be time-consuming and more controversial than the relaxation of state aid rules. If, however, the relaxation of the rules continues without European funding, the EU will take a decisive step towards the fragmentation of the single market.