Eurostat publishes the indicator «young people neither in employment nor in education and training», abbreviated as NEET, which corresponds to the percentage of the young population who is not employed and not involved in further education or training. The percentage of NEETs continuously decreased until 2019. However, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic the share of young adults neither in employment nor in education or training rose. In 2021, the proportion of Europeans aged 15 to 29 who were neither working, studying nor participating in a training program increased to 13.1% of the population (compared to 12.6% in 2019).

The purpose of the NEET index is to monitor the difficulties of the transition process of young people from education and training to the labor market. It is often young people who bear the heaviest cost of economic crises- this was the case with the 2020-2021 coronavirus crisis, the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, and the 2010-2014 euro crisis-. In a crisis, jobs occupied by young people are among the first to be lost, while few new jobs are created.

By definition, even if they have formal qualifications, young people have not yet acquired the informal qualifications that come with work experience. Therefore, without an effective system of connecting businesses with vocational schools that offer meaningful apprenticeships, many young people find it difficult to join the labor market. When they finally do, the jobs they find are often precarious, poorly paid, or both: young people are overrepresented in temporary jobs, while it takes a longer time to become established on the labour market compared to previous generations.

Today the new generation will start their professional careers in a labor market that has been adversely affected by the recent pandemic and geopolitical tensions, as well as by the longer-term transformations resulting from the digitalization of the economy and the need to address climate change (“green transition”). In this context, obtaining the appropriate qualifications and facilitating the process of integration of young people into the labor market emerge as key issues for their future well-being. To underline their importance, Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission, declared 2022 the “European Year of Youth“.

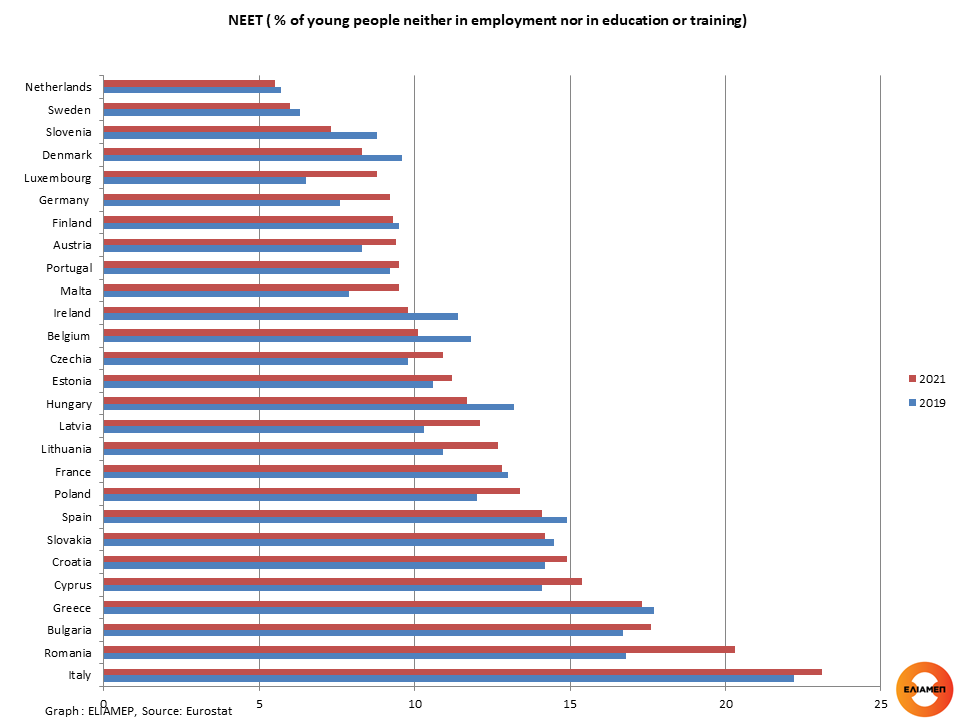

The difficulties faced by young people in the transition from education to the labor market are not the same in all Member States. In 2021, the NEET rate ranged from 5.5% (in the Netherlands) to 23.1% (in Italy). Sweden (6%) and Slovenia (7.3%) also performed well, while Romania (20.3%) and Bulgaria (17.6%) performed negatively. Greece (17.3%) had the fourth worst performance in 2021, although it saw a slight improvement on 2019 (17.7%), which was the case in only 11 of the remaining 26 Member States.

Indeed, in most countries the NEET index has increased in recent years. In some countries, the increase was notable: Romania (+3.5 percentage points), Luxembourg (+2.3), Lithuania and Latvia (both +1.8 points), even in Germany (+1.6 percentage points units).

NEET index also varies according to the level of education. Among young people with a low educational level, the relative percentage was higher (15.5% in 2021 in the EU as a whole) and increased more after the pandemic (from 14.3% in 2019). After all, the coronavirus crisis affected low-skilled workers the most because they were unable to work remotely. In contrast, among university graduates the NEET rate was lower pre-coronavirus (9.4% in 2019 in the EU as a whole), and decreased in2021 (to 9.2%).

Greece is the only country where the proportion of young people not in education, training or employment is much higher for university graduates (26.8% in 2021, almost three times higher than the EU average) than for young people with a low level of education (7.9%, almost half the EU average). Furthermore, while for young people with low education the relative percentage has decreased in recent years (it was 9.5% in 2019), for young people with a higher level of education the NEET index has increased (from 25.9% in 2019). In all other Member States, the opposite happened.

What is the reason for this impressive Greece-EU divergence? Simplifying, on the one hand the education system produces too many graduates that lack basic skills : according to the latest OECD PIAAC report (2015), 18.7% of tertiary graduates aged 20-34 lacked basic skills on literacy, numeracy and problem solving. On the other hand, the Greek economy continues to create mainly low-productivity jobs, while Greek companies continue to refrain from training their employees.

To address the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on young people, in July 2020 the Commission proposed extending the existing ‘Youth Guarantee’ schemes to young people up to 30 (previous schemes covered ages under 24). Youth Guarantee schemes have since 2014 offered training, education or work to 24 million young people in the EU. All Member States have committed to the implementation of the Reinforced Youth Guarantee offering ‘good quality jobs, training or traineeships’ to young people who sign up to the schemes.

But difficulties remain. The voluntary nature of the EU programs (currently a Council Recommendation) has been criticized by MEPs. In the wake of the pandemic, the target of reducing the NEET rate to 9% by 2030 has been pushed back.

In 2016, Jean-Claude Juncker, then President of the European Commission, said: “I cannot and will not accept that Europe is and remains the continent of youth unemployment.” As the problems of young people’s integration into society and the labor market persist, the European Parliament’s call on the Commission to propose a youth guarantee instrument that will be binding on all Member States becomes timely.