The policy brief* outlines the agenda of the new Commission before the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic, and aims to analyse the ways in which the crisis has reinforced and strengthened key points of that agenda. It further outlines the Commission’s Recovery Plan proposal, and examines its links to the aspiring green and digital transition. Finally, it showcases the legal base and timeline of the Recovery Plan proposal and highlights the main points of agreement and contention across the Member States, outlining the July deal of the European Council and the ensuing resolution of the European Parliament. It overall argues for the need of a holistic recovery, that takes into account the unprecedented policy window brought by public and private funding, and ensures that the eventual indebtedness of the next generation is at least compatible with the aspirations and goals of an economy and society of the future.

You may find the Policy brief by Christina Kattami, Economic and Policy Analyst, European Commission, in pdf here.

*Disclaimer: The information and views set out in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official views of the European Commission

The past agenda setting – Introduction and context

In December 2019, the new von der Leyen Commission took charge with six political priorities, three of which are concretely forming Europe’s new growth model. The European Green Deal actions, the Europe fit for the digital age strategy and the agenda for a social economy aspire to shape the EU’s future as a green, digital and resilient society.

“The von der Leyen Commission took charge in December 2019, with the aspiration to create Europe’s new green, digital and resilient model of growth”

The European Green Deal headlined bold and ambitious actions aiming for Europe to become the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. These actions range from proposals to revise carbon pricing fairly and effectively, to guidelines of building efficient housing, to energy taxation and carbon border adjustment mechanism plans, to action packs rendering production and consumption sustainable, like the Circular Economy Action Plan or the Farm to Fork Strategy.

The Digital Europe agenda aims to ensure that digital technology transformations reach their full and fair potential for people and businesses, while helping to achieve the climate-neutrality target of 2050. It involves actions ranging from data protection to infrastructure for digital networks and services (such as the rollout of 5G), to targeting investments in digital skills and education for the next generation.

A mainstreaming point underlining both these aspirations is that the ensuing deep and structural transitions have to be just, fair and ‘leaving no one behind’. This is highlighted, for example, in the Just Transition Mechanism, part of the European Green Deal, which aims to compensate the regions, workers and businesses that will benefit the least from the transition process, such as coal-intensified businesses and displaced workers. At the same time, the fairness action plan is also highlighted by the aims of a strong Social Europe which uncovers ways to strengthen just transitions, including establishing fair minimum wages for European workers, a European Unemployment Reinsurance Scheme, a reinforced Youth Guarantee, and stronger reskilling and upskilling points for the future.

These three policy priorities spanning over the timeline horizon of the von der Leyen Commission (2019-2024) created the new mainstreaming agenda for Europe’s future actions and directions: a twin green and digital transition leaving no one behind.

“As we move from crisis response to crisis recovery, we realize that COVID-19 has actually reinforced the urgency of the past agenda”

The present gamechanger – COVID-19 and the green, digital and social agenda

The coronavirus pandemic brought a public health challenge, and a socioeconomic scare, of unprecedented dimensions. Putting a halt in the ambitious new agenda of the Commission, the institutions were faced with one of the most challenging peacetime situations in the Community’s life.

The pandemic mandates all resources to target the health and safety of the citizens, and is a gamechanger for any policymaker. The bleak version is portrayed in the Spring economic forecasts, where the EU economy as a whole is projected to contract by 7.4% in 2020, far deeper than any of the aggregate metrics of the 2009 financial crisis, with individual contractions ranging from Poland’s 4.3% to Greece’s staggering 9.7% (European Commission, Spring Economic Forecast 2020). However, as we move from crisis response to crisis recovery, we slowly realize a simmering silver lining, and that lies in what the pandemic managed to uncover. Louder than any policymaker, stakeholder or protestor, the pandemic proved the green emergency, the digital potential, and the exacerbation of social vulnerabilities; thus reinforcing the necessity of the ‘past’ agenda.

The pandemic’s green effect

“The second half of 2020 saw the largest decrease in CO2 emissions in history”

The COVID-19 crisis achieved in a couple of months what environmentalists have been trying to realize for decades. The freeze of production did not just expose the unsustainability of modern global value chains, but ensured that the second half of 2020 saw global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions fall by more than any other year on record.

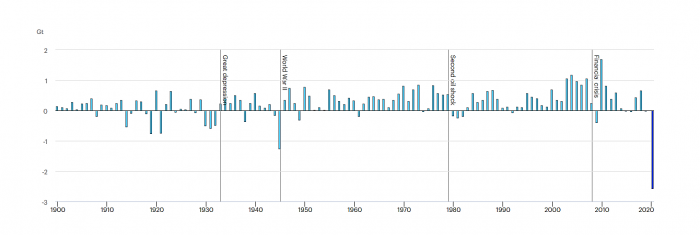

Figure 2.1 – Annual change in global energy-related CO2 emissions, 1900-2020

Absolute terms (Gt)

Source: International Energy Agency, 2020

As the graph above shows, the absolute decrease of GHG (2.6 Gt of CO2) is double the decrease in the Second World War, almost six times the decrease of the 2009 Global Financial Crisis, and by far the largest absolute decrease in the last century.

Nevertheless, on its own it is of little significance; the UN Environment Programme estimates that global GHG emissions must fall by approximately the same amount as the 2020 fall every single year from 2020 to 2030 to manage to keep temperature increases to less than 1.5°C (UNEP, 2019).

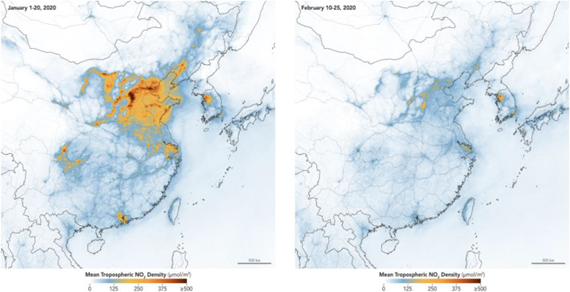

Figure 2.2 – Concentrations of nitrogen dioxide across eastern China, January (before quarantine) and February 2020 (during quarantine)

Source: NASA Earth Observatory, 2020

The green effect has been tangible in air pollution levels across the world, as well as examples of flourishing biodiversity being revived in a matter of months, and has been dubbed by many as the Earth advantage of the crisis.

…could easily be short-lived

At the same time, the historical paradigm of crises shows that a GHG reduction is only transitory and very short-term. As a quick example, Graph 2.1 indicates how in the global financial crisis, the initial 2009 decrease was followed by the largest absolute increase in GHG energy-related emissions ever.

There is a simple explanation for this phenomenon – the focus of governments after economic crises is on quick rebound of economic activity, not suitable for the deep and structural infrastructures which are essential in a sustainable transition. In the 2009 case, the rebound in GHG was attributable to governments investing heavily in fossil fuel dependent economic activities with utter aim to stimulate domestic economies, together with low energy prices. (Peters et al, 2011)

This trend is already happening. Despite new rhetoric and hype from many countries in support of a ‘green recovery’, governments have been spending vastly more in support of fossil fuels than on low-carbon energy in coronavirus rescue packages: G20 countries have spent or earmarked at least €130 billion of bailout cash to support fossil fuels (noting that the United States is the most responsible for this total amount), with only approximately one fifth of the spending being conditional on environmental requirements. Only half of the same amount is spent on clean energy in recovery packages.

“Historically, the years following the economic crisis see massive increases in emissions, as governments focus on quick economic activity rebounds. The same is happening already.”

If environmental claims do not move policy makers, there is a further resilience argument to be made on the connection between ecological sustainability and pandemic expansion. Specialists are increasingly arguing that disease spillover from animals to humans is on the rise worldwide, largely as a result of our growing ecological footprint, deforestation and other changes to land use, and the way commercial agriculture and mass production is managed. The ensuing logical argument is that protecting our ecosystem and working towards climate targets is enhancing world resilience in preventing, and reacting to, future pandemics.

The pandemic’s effects could mark a turning point in the fight against climate change, as it has proven the economic and environmental negative externalities of our production and consumption modes; or it could simply be a short-lived example, if governments decide to follow the historical trajectory that previous crises have built for them.

The pandemic’s digital effect

“Europe saw 4 out of 10 workers beginning to work from home as a result of the crisis.”

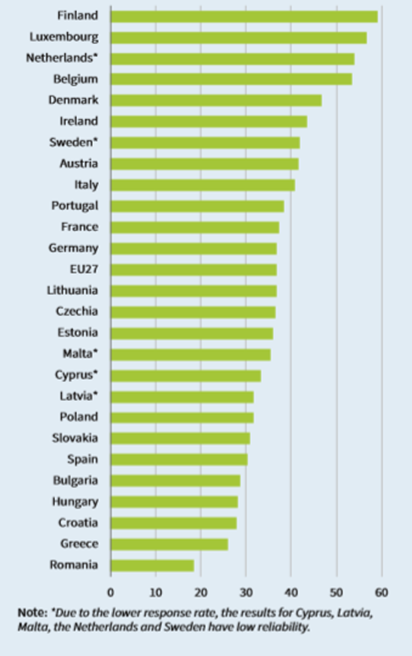

Perhaps what COVID-19 did the most was prove the potential of – and ensuing dependence on – digitalisation, as well as the urgency for its accurate and up-to-date regulation. Setting aside the bombardic increase of digital communication platforms, the rise of teleworking has been momentous, and crucial in protecting employment during lockdown and quarantine. As showed in Graph 2.3, across the EU, the proportion of workers who started teleworking as a result of the pandemic ranged from Romania’s 18% to Finland’s 58%, with the EU27 as a whole seeing almost 4 out of 10 workers beginning to work from home. The same report argues that there is a negative correlation between teleworking and decrease of work, suggesting that, alongside job retention schemes, the extent that one could telework, could actually protect their employment as a whole (Eurofound, 2020).

Figure 2.3 – Proportion of workers who started teleworking as a result of COVID-19 by country (%)

Source: Eurofound, 2020

Recent evidence shows that not all potential for teleworking is fully exploited. Overall, with the exception of the older workers, the share of workers actually teleworking is about 10 percentage points below the potential. The evidence shows that there are around at least 30% of total jobs by country that can potentially be executed remotely (OECD Employment Outlook, 2020); and as such, more jobs that can prove resilient in acute employment shocks like the one we are experiencing now.

…mandates accurate and up-to date infrastructure

This new reliance on teleworking and platform usage proves the importance of holistic digital strategies, including advances in data protection regulations, infrastructure in technology potential, and investment in digital skills. As a whole, digitalisation changes the forms and standards of work, gives birth to new contract types and raises questions of access inequality. It is very likely that COVID-19 has given policymakers an insight to the future of work and labour markets, where digitalisation plays a much bigger role than initially envisaged.

The pandemic’s social effect

“While the virus knows no boundaries, its effects do, and have been dis- proportionate across income, age, gender and contract type.”

The pandemic may know no boundaries, but its effects do. The pandemic health and socioeconomic effects, as well as the quarantine and lockdown measures, have been unequally spread across income distribution, gender, age and structure of work, with the pandemic’s burden being borne the most by society’s most vulnerable. This includes low-paid workers, atypical workers (part-time and self-employed), women and young people, all of whom have faced disproportionate effects either directly, because of greater difficulties in protecting themselves in health effects, or indirectly, via the impact of the lockdown on their jobs.

Across the OECD, only 14% of the top-quartile earners stopped working as a result of the pandemic, while the same percentage for the bottom-quartile earners was 30% (OECD Employment Outlook, 2020, p.18), often because they simply could not work from home. At the same time, in the EU, the unemployment rate in March increased by 4.5% for women, against 1.6% for men (Eurostat). One explanation for this is that many of the industries directly affected by COVID-19 (i.e. retail sector, accommodation services like hotels, and food and beverage services) are also major employers of women (ILO 2020 labour statistics on women), while, it is likely that the widespread school and childcare facility closures during the crisis also amplified women’s unpaid work burden at home. Additionally, atypical workers have often been excluded from government support schemes during the COVID-19 crisis, such as temporary wage subsidy schemes or short-time work schemes, and have not been accounted overall in the social welfare state. Finally, young people are facing the second ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ economic downturn in ten years, and recent graduates are trying to enter a labour market at its bleakest state, at a time when youth unemployment steadily persists at double or higher the general unemployment levels (Eurostat).

…proves the exacerbation of existing social vulnerabilities

The inequality effects of the pandemic may only now be starting to arise, but it is clear that its effects are, and most likely will also be, disproportionate; thus requiring just and fair policies in the future agenda setting.

The pandemic and the state

A nuanced point the pandemic proved was the return of the state. Decisive interventionism is not only supported by the public, but mandated and expected, and something to be evaluated in later stages. The view that market cannot be trusted as such has prevailed, because it nurtured unsustainable global chains and allowed crucial supply shortages to exist.

“COVID-19 proved the return of the state.”

In the beginning of the crisis, the public looked to the state to stabilise infection rates, protect the health systems from being overwhelmed, and eventually save lives. Now, the public is looking to the state both for short-term crisis aversion in a second wave, but also for long-term socio-economic recovery.

“In an area of no legal competence, the European platform was nonetheless expected to act.”

An argument can be made that the European public went beyond the state. In an area where the European Union does not hold any legal competence apart from ‘supportive’ (health), the public accused the institutions of inaction, and in-solidarity amongst Member States, demanding an immediate pan-European response. This mandate becomes even more important when it comes at a time of re-isolationism across the Atlantic, and when we know that other lurking emergencies, notably the climate threat, are simply too big for the nation state to deal with.

The future challenge – A holistic recovery plan

It is against this context that the EU’s Recovery Plan was designed, in the aspiration that the recovery package can kill many birds with one stone. Rather than repeating the mistakes of the 2009 financial crisis in reaffirming the unsustainable production patterns of the past, the recovery plan aims to ensure that the twin transition, and its accompanying social fairness, are stimulated in the European investment and reform path to recovery. This section outlines the Commission proposal and its links with the green, digital and social agenda, while the following section showcases the reality of the agreement around the Recovery Plan, highlighting its legal base, timeline and the recent deal of the European Council, as well as the ensuing resolution by the European Parliament.

The Recovery Plan Proposal

“The Recovery Plan has been dubbed as Europe’s green Marshall plan.”

Put forward on May 27, the recovery plan proposal combined:

- A revamped EU long-term budget: €1.1 trillion Multiannual Financial Framework 2021-2027

- A new Recovery Instrument: the Next Generation EU fund of €750 billion to be financed through joint debt issued by the Commission on behalf of the Member states (see Box 3.1)

Together, they bring the Recovery Plan at a €1.85 trillion package.

The (temporary) Recovery instrument, Next Generation EU, is based on three pillars; broadly, a) one for supporting Member State recovery focused on national recovery plans, b) one for kick-starting the economy focusing on stimulating investment, and c) one for learning the lessons of the pandemic crisis focusing on health initiatives.

Figure 3.1 – A total Recovery Plan amounting to 2.4 trillion: 1.85 trillion proposed on top of 540 billion already in place:

This proposal comes on top of safety nets put in place, such as the temporary Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency (SURE) aiming to support workers at risk of losing their jobs because of the crisis, as well as investment stimulus and support from the European Investment Bank and the European Stability Mechanism, all amounting to a total of €540 billion.

Links to the green, digital and social agenda

The entire Recovery Plan reaffirms its respect in investing in a green, digital and resilient Europe. Some mechanisms, as per outlined below, provide a more direct link to those goals.

1. Recovery and Resilience Facility

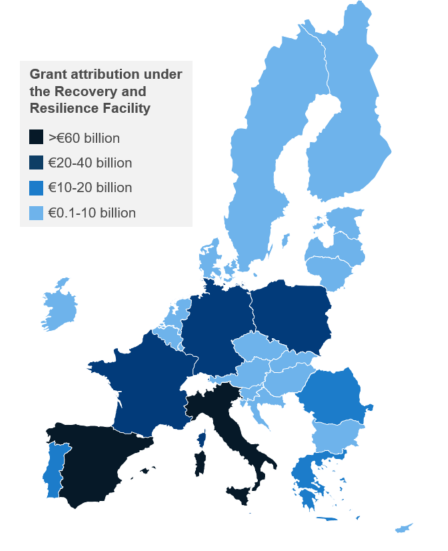

The RRF, the most discussed facility of the Next Generation EU fund, will be the main instrument in supporting EU countries address the coronavirus crisis and recovery. It aims to provide financial support to both public investment and reforms. In the Commission proposal, it takes the form of €310 billion in grants, with the possibility of the Member State to ask for up to €250 billion in loans. The Commission has already published an allocation key for the grants of each Member State based on its effect from the coronavirus crisis, through a mix of population, GDP per capita and unemployment rate (see map in section 4).

The innovation of the facility lies in its conditionality for the Member States to receive their funding. Replacing the one-dimensional fiscal goals of the past, conditionality this time is explicitly linked with the green and digital agenda, as well as taking into account already recommended reforms for country growth, equality and socio-economic resilience. Governments must first submit their national recovery plans to the Commission, and must showcase how the recovery plan will:

a) address the main challenges identified in the European Semester, the EU’s main economic coordination procedure, as well as facilitate the implementation of the European Pillar of Social Rights;

b)ensure adequate focus of these investments and reforms on the challenges related to the green and digital transition.

As such, the link of the Recovery Plan funds and the twin transition is tangible, and conditional. Because of its crucial role in the Recovery Process, the RRF has been one of the main contention points in the negotiations, and touches upon debates of fundamental nature (see the following section).

2. REACT-EU (Recovery Assistance for Cohesion and the Territories of Europe)

A new initiative in the proposal aims to extend the crisis response and repair measures that cohesion policy has started, while enlarging the scope to cover green, digital and growth-enhancing investments. It includes a 55 billion top-up of the current cohesion policy programmes in the short-term; it notably increases the European Social Fund, which focuses on upskilling and reskilling, education, youth employment and mobility. REACT-EU as a whole focuses on issues of just transition and fair recovery amongst European regions.

3. A larger Just Transition Fund

To assist Member States in accelerating the transition towards climate neutrality, the Commission had put forward the Just Transition Mechanism, compensating regions, businesses and workers who will have to adjust the most to the transition needs. The Mechanism included a fund of €7 billion, which was proposed to be increased five-fold, and strengthened up to €40 billion, to ensure that the recovery includes a just transition towards climate neutrality. The significant top-up shows the focus of recovery towards the twin transitions occurring in a fair fashion.

4. InvestEU and strategic investments

The proposal further suggests to strengthen Europe’s flagship investment programme, InvestEU, and focus it more on investing in key value chains crucial for Europe’s future resilience and strategic autonomy, such as sustainable infrastructure and digitisation, in the context of the twin transition. InvestEU is the expansion of the successful Juncker Plan model of using an EU budget guarantee to crowd-in other investors, and is expected to mobilise at least €650 billion in additional investment between 2021 and 2027.

5. Solvency Support Instrument

At the same time, this new instrument aimed to provide urgent equity support to sound companies put at risk by their crisis, while supporting their green and digital transformation. It aspired to mobilise €300 billion for the real economy.

6. New Health Programme and rescEU

The third pillar of the Next Generation EU instrument is dedicated to learning lessons from the pandemic, and reaffirms the social and resilience focus of the recovery plan. The new Health programme aimed to distribute grants in EU healthcare systems with a focus on health security and capacity to react to crisis, as well long-term disease prevention and surveillance. RescEU will reinforce the civil protection support capacity to respond to large-scale emergencies, such as health emergencies infrastructure for response.

7. New budget revenue streams

To finance the higher proposed EU budget, the Commission has proposed new and diversified sources of revenue that contribute to EU priorities, and in particular climate change, circular economy, digitalisation and fair taxation. Those include an extension of the Emissions-Trading System and a digital levy on tech giants. Proposing revenue sources (and taxation streams) that are linked to the green, digital and social agendas is a new concept for the EU budget, which has traditionally been financed by custom duties and Member State contributions, and reinforces the European commitment to its priorities.

“The proposed own resources are all based to green and digital claims, linking the budget with the priorities of the Union.”

“If we are going to indebt our future generations in an effort to get out of the crisis, we also have to think about what future society we want to be offering them’– Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz at the London Climate Week 2020.”

The Recovery Plan as a whole reaffirms what leading academics, policymakers and stakeholders have called for in the past months: that the recovery should reflect the society we want to see the day after the crisis (see Stiglitz et al, 2020, amongst others, calling for a green recovery). Dealing with the crisis will bring significant debt in the world; just in the EU-27, the aggregate debt-to-GDP ratio is projected to reach 95%, with the euro-area reaching a new peak of 103%, while the Maastricht fiscal rules mandate this number to be at 60% for every Member State (European Commission, Spring Economic Forecast 2020). Thus, the argument for a holistic transitionary recovery is further strengthened when one considers the intergenerational dimension of the crisis; which will leave the younger generation not only heavily indebted but also alone to deal with the future costs of the climate emergency.

The reality – The political minefield

Agreeing on the long-term budget of the EU has historically being the political minefield in European negotiations. It includes the superhuman task of aligning and appeasing 27 crude national interests on the direction of the budget and the EU as a whole. The European Council (EUCO) agreement of the 21st of July was realized under the record-breaking negotiation duration of five days[1]; came after a failed attempt at a political agreement in June; and was followed by a European Parliament resolution on the 23rd of July which did not accept the political agreement as it stands. Even though the latter is not legally binding, the Parliament has a veto right over the final EU long term budget, and its resolution has set the mood and the context for the upcoming trilogue negotiations between the Parliament, the Council and the Commission.

As the timeline shows, arguably the greatest leap in the political agreement towards the Recovery Plan may have indeed been made, but ensuing negotiations with the European Parliament, as well as national ratifications, ensure that the agreement is far from a done deal.

Legal Base and timeline of the Recovery Plan

As laid out in Article 312 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU, sealing the Multiannual Financial Framework regulation requires the unanimity vote of the Council of the EU following a political agreement in the European Council, and the majority voting (‘consent’) of the European Parliament.[2]

Council unanimity is already a challenging target to achieve. The MFF package additionally involves a Commission proposal for changing the EU’s ‘Own Resources’, something which defines the size and methods of financing the budget as a whole (see Box 3.1). This would require an additional quasi-constitutional legal procedure, where, on top of Council unanimity, the Commission proposal has to be ratified by every Member State, according to its constitutional requirements. (Art 311, TFEU). ‘Constitutional requirements’ in this case usually takes the form of a ratification in national parliaments, but it can also include a country-wide referendum in some cases. The European Parliament here does not have a binding role, much unlike the veto power it holds for the MFF negotiations.

On top of this, there are new timelines in place for the Member States to submit their recovery plans under the Recovery and Resilience Facility to the institutions. As such, there are three timeline challenges that need to be met:

- MFF 2021-2027 – Requires the final agreement by the two co-legislators, the Council and the Parliament, which ideally is aspired for October, in order to be able to begin the implementation of the new budget on the 1st of January;

- Own Resources Decision which includes potential new resources and the joint debt financing of the Next Generation EU – Requires the final agreement on Council level by unanimity, the (non legally binding) opinion of the European Parliament and the ratification of the deal in every national parliament, all of which has to be realized by December;

- National Recovery and Resilience Plans under the Recovery and Resilience Facility – Requires the Member States to submit their plans to the Commission by October, so that the assessment by the institutions can begin, and the Member State can eventually receive funding accordingly.

The timing becomes ever more important as the European Council July Deal rejected a ‘bridge’ transition proposal of the Commission, by which the current MFF 2014-2020 would be increased to ensure that funds are available before January 2021. As such, the Council insisted on the initiatives already in place.

The Politics

What the Member States agree on

In the overall picture, a lot; in the details little.

Necessity and Urgency

All Member States recognize the need for immediate action, as well as a European approach towards the ensuing recovery, and most Member States have been publically pushing for a deal as soon as possible.

Green and Digital links

“Some countries have already established green recovery links; but some others lag far behind.”

Most Member States have at most welcomed, at least not opposed the link of recovery with the green and digital transition. Some Heads of State announcing already that the national recovery plans will ensure investment towards the twin transition. Additionally, some Member States have even already linked their recovery policies to green goals. France’s state aid policy in the €7 billion bailout for Air France-KLM has green strings attached – for example, it mandates the airline to eliminate short-haul flights for routes covered by high-speed trains. This approach is not shared by all Member States; by contrast, the Italian government’s €3 billion support plan on Alitalia did not have similar conditions. At the same time, the resistance of a minority of Member States, such as Poland, who is the only Member State that has not signed the 2050 climate neutrality agreement, can still be tangible, albeit not being the priority of the negotiation’s fighting points. Indeed, interestingly enough, the green and digital transition base of the Recovery Plan was only but a small part in the intense negotiations of the July EUCO Summit.

With the EUCO July deal, an overall climate target of 30% applies to the total amount of expenditure of both the MFF and the Next Generation EU. It additionally mandates sectoral legislation to comply with the objective of EU climate neutrality by 2050 and contribute to achieving the Union’s new 2030 climate targets. Additionally, all EU expenditure needs to be in line with the Paris Agreement objectives and the ‘do no harm’ principle of the European Green Deal. In practice, the extent of this remains to be seen.

What the Member States disagree on

While the necessity of a European recovery response is clear to all, many points of fundamental contentions, core to national interests, threatened (and continue to do so) the agreement of the final package. The disagreements show profound political lines across Europe, cutting deep across geopolitical divisions and taboo thematics, as the run up to the Recovery Plan brought up old wounds of moral hazard, no bailout principle and non-solidarity, and leaders warning that a failure to act would mean the ‘end of Europe’.

The points below outline the content of the disagreement, and highlight what was agreed in the European Council so far, as well as what the European Parliament has expressed in its ensuing resolution.

Loans versus Grants

The debate on whether the recovery instrument, which will incur joint debt backed by all 27 Member States, should allocate funds to be repaid back (loans) or not (grants), is the point that reflects the most the philosophical question over EU solidarity. Smartly based on both the Franco-German proposal of a €500 billion recovery fund based only on grants, and the counter-proposal of the ‘Frugal’ states (Netherlands, Austria, Sweden, Denmark) of a €250 billion recovery fund based only on loans, the Commission’s Next Generation EU combined the two: €500 in grants and €250 billion in loans (ergo the €750 of the Recovery instrument).

The Proposal also managed to avoid touching the taboo Eurobond debate by issuing its own joint debt on behalf of the Member States; by collectivizing the debt in its name, it is dampening the rhetoric of the ‘debtors’ owing to the ‘creditors’. However, its spirit remained in the loans versus grants debate. Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden and Finland strongly persisted on the reduction of the grant balance, while the rest 22 Member States argued that using only loans would completely disregard the disproportionate effect the pandemic has had on health and socioeconomic issues, and would fail any hope of European solidarity.

EUCO July Agreement: proposes that the size of the Recovery Instrument (750 billion) and its financing type (joint debt issued by the Commission) remain unchanged and in line with the initial proposal. However, total grants are limited to €390 billion, and total loans to €360 billion. Grant allocation is based on an allocation key indicating the impact of the coronavirus crisis on each Member State (see map below). The maximum value of loans for its Member State cannot exceed 6.8% of its GNI.

European Parliament July Resolution: takes a strong stance against this development and ‘deplores’ the cuts to the grant components, arguing that this would undermine the recovery efforts by decreasing the firepower of the instrument and its transformative effects.

Conditionality of the grants

As aforementioned, the Commission has proposed linking the funding of the Recovery and Resilience Facility to the European Semester process and the twin transition. Under the proposal, capitals would be required to show in their recovery plans a clear link to fighting the pandemic effects and stimulating, or at very least not hindering, the twin transition. Although the link to the European Semester is clear in the proposal, the details and degree of flexibility of reforms remained open questions in the negotiation. Some Northern states advocated for stricter forms of conditionality, with notable example of the Netherlands pushing for Council unanimity in passing each national recovery plans. The strict conditionality has been a red line for the South and the East, with primary example of Greece vowing that the country will not accept strict EU conditions on the use of coronavirus emergency aid.

EUCO July Agreement: proposes that the national recovery plans have to be approved by the Commission and by the Council, but by Qualified Majority Voting in the latter rather than unanimity. However, an ‘emergency brake’ system is put in place to pause the disbursement of the transfers; it would allow at least one Member State with reservations about the recovery plan presented by another country to open a debate amongst the EU27 at the level of the Ecofin Council, or, in disagreement there, in the European Council.

European Parliament July Resolution: opposes this development, by arguing that it will complicate the procedure and weaken its legitimacy.

Allocation key for funds of the grants

Finding the correct algorithm for allocating the grants in the Member States is, of course, another issue in the political arena. The Commission proposal already put forward an allocation key for the €310 billion of grants available under the Resilience and Recovery Facility based on a formula that takes into account unemployment between 2015 and 2019. Some Western governments argue that the criteria should better reflect the impact of the pandemic; simultaneously, Eastern leaders are concerned that it will be the Southern states that would benefit from the formula’s design.

EUCO July Agreement: The allocation key will rely on the original Commission formula for the first two years of the Recovery instrument (2021-22) and on a new formula dependent on the overall impact of the crisis for the last year of the instrument (2023).

European Parliament July Resolution: raises no significant objection to the proposed allocation.

“The budget negotiations are at their very core zero-sum games, and the EUCO deal reduced the size of the EU long term budget; meaning that cuts had to be realized.”

Final Size, and Zero-Sum deals, of the long term Budget

The final size of the recovery plan combines the €750 billion of Next Generation EU with the €1.1 trillion of the MFF, bringing it to a total of €1.85 trillion. Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden and Finland advocated for an overall lower level of spending. At the same time, Southern leaders, as well as several leaders of the European Parliament have called for a far bigger MFF than either the Commission or the Council have proposed in the past. Size matters most when considering that budget negotiations at their very core are zero-sum games – if an area is increased, another one has to suffer cuts.

EUCO July Agreement: puts forward the following: a) albeit leaving the (temporary) recovery instrument at €750 billion, the total size of the MFF is decreased to €1.074 trillion; b) the Recovery and Resilience Facility is increased from €540 to €672.5 billion[3]. However, c) significant cuts were incurred to important instruments such as the Just Transition Fund (only €17.5 from the proposed €40 billion were kept), the InvestEU plan, and the Horizon Europe research framework programme while d) the Solvency Support Instrument as well as, crucially, the new EU Health programme, were completely nullified.

European Parliament July Resolution: strongly opposes these cuts, particularly concerning the new EU Health Programme, the Solvency instrument and the Just Transition Fund. It argues that a 2021-2027 MFF below the Commission proposal is neither viable nor acceptable.

New own Resources

The proposals for new own resources (see Box 3.1), and recovery fund reimbursement, remain too ambitious for some national capitals. A tax on digital giants, a carbon border tax, a tax on non-recycled plastic packaging waste and an expanded Emissions Trading System, are all very controversial and have been put forward already in the 2018 Proposal for new Own Resources without an effective agreement. The latter two are the ones with the best chance of approval, and even they are controversial; just to showcase, using revenues linked to the Emissions Trading System is opposed by six Member States of diverging nation interests, Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Romania and Estonia.

EUCO July Agreement: proposes a first step for a new own resource based on non-recycled plastic waste that will be introduced and apply as of 1 January 2021. A Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism; a digital levy; an extension of the emissions trading system (ETS) to the maritime and aviation sectors; and a Financial Transaction Tax (FTT) are all mentioned in the agreed text. These are all potential new own resources, and still have to be formulated into legislative proposals by the Commission, as well as, crucially, be eventually ratified by all national parliaments.

European Parliament July Resolution: Stresses that the progress is not satisfactory and pushes for a legally binding calendar for the introduction of new own resources, including proposals of new resources on top of the ones agreed.

Rebates

The (controversial) rebates have been used in the past to return part of the budget to the ‘net contributor’ countries, who contribute more to the budget as part of their higher GNI. The initial 2018 plan mandated the immediate phase out of the rebates, resulting in the receiver countries, including the frugal states, seeing steep increases in their budget obligations. Offering an olive branch to the net contributors, the new Commission proposal argues that with the enlarged MFF size, rebates will be phased out in a longer period than initially expected, minimizing the losses the net contributors expected to see.

”

Even though certain to be phased out in the Commission proposals, the controversial rebates were actually increased in the EUCO deal, despite the overall decrease of the MFF.”

EUCO July Agreement: proposes rebates to be increased for the Netherlands, Austria, Denmark, Sweden and Germany, despite the early plans from the Commission to phase them out by 2027. The lump-sum corrections have grown significantly for the mentioned countries – nearly tripling in the case of Austria. The deal also increases the so called ‘collection costs’ on other Own Resources (duties). These include, for example, custom duties in Member State entry points, the collections of which have to go to the EU budget. Member States are now able to keep more of the amount collected in the name of the EU, something which benefits the Netherlands, amongst others, in particular.

European Parliament July Resolution: takes an absolute stance against the increase of the rebates, and reiterates its firm position of ending all rebates and corrective mechanisms altogether.

Rule of Law

A crucial ongoing debate, particularly given the situation in Member States like Hungary and Poland, is whether receiving EU funds should be linked conditionally to the EU values, and crucially the Rule of Law. During the EUCO Summit, a mechanism on this issue was discussed, but with Hungary already threatening to veto the agreement before the Summit begun, expectations were low. A potentially indirect link with the Rule of Law can be found in the conditionality of the recovery plans with the European Semester, where its Country Specific Recommendations also include references rule of law questions.

EUCO July Agreement: The budget conditionality on the rule of law is present, albeit significantly limited and vague, without a fleshed out mechanism in place.

European Parliament July Resolution: Found that the Council weakened the efforts to uphold rule of law, fundamental rights and democracy in the framework of the Recovery Plan, and stresses the need to progress the Rule of Law Regulation as a top priority for the Parliament.

Next Steps

- Trilogue negotiations between the Council, the European Parliament and the Commission to begin, with aim to arrive to the final deal of the recovery plan by October.

- National parliaments will have to approve the own resources decision swiftly after the agreement.

- MFF 2021-2027 aspires to enter into force together with the Next Generation EU recovery Fund on the 1st of January 2021.

On the recovery plans:

- Governments to submit their recovery and resilience plans to the institutions until October.

- The Commission to review the national plans within two months of submission (according to the EUCO agreement).

- The Council to approve the assessment of the plans within four weeks of the proposal with qualified majority (according to the EUCO agreement).

Conclusion

The COVID-19 crisis has brought an unprecedented challenge, and requires unprecedented solutions. It re-instated the emergency of the climate threat, the potential of the digital economy and society, and the urgency for social fairness and solidarity. It rendered the past agenda ever more relevant and mandated immediate action.

“Next Generation EU needs to prove itself worthy of its name: learn lessons of the past, transform structures of the present, protect generations of the future.”

The Commission’s Recovery Plan proposal recognizes this, and aims to capitalize a once-in-a-lifetime policy window of unprecedented public and private funding, to guide the economy to a sustainable direction. Despite its contentious points, the deal put forward by the European Council managed to keep many firsts in the history of the bloc. Even if stamped as temporary, it is the first time in history that the Union can issue common debt on behalf of the Member States, something unthinkable just a few months back, and something which raises questions on the potential future of a fully-fledged fiscal union. It is the first time that EU climate aspirations are profoundly integrated and mainstreamed throughout the budget. The first time that conditionality is not based on fiscal targets, but on the goals we want to see in the EU model: fighting climate change, digitalising the economy, and ensuring socioeconomic resilience. It is the first time that own resources are linked to EU policies and aspirations, rather than EU logistics. All of that while the EU currently holds one the most profound recovery plan models in size and type.

In an interesting sense, the pandemic and the climate threat, in particular, are emergencies of the same nature; neither virus molecules nor CO2 droplets know any state boundaries; both involve market failures and externalities; require complex science; and raise questions of international cooperation, systemic resilience and sustainable models. They both cause intergenerational unfairness, as the indebted future generations will have to deal with the debt incurred today and the burdens of inaction in the face of the climate threat. As such, the least that today’s Recovery Plans can do, is ensure that lessons of the past are learned, that structures of the present are transformed and that the needs of the next generations are reflected

[1] The record negotiation time-breaking is potentially coming second only to the 2000 Nice European Council negotiations, with a difference of approximately 25 minutes.

[2] Legally, it is the Council of the EU, in its General Affairs formation (i.e. the meeting of typically the European Affairs ministers of each Member State) that eventually votes on the Commission proposal. In practice, however, it is the unanimity agreement of the European Council (i.e. the heads of State) that guides and eventually defines the decisions of the Council of the EU.

[3] The new upped size brought a very slight increase of grants from €310 billion to €312.5, and a significant increase in loans from €250 to €360 billion. Another €77.5 billion grants are attributed in the Next Generation EU fund, under other programmes, making the final grant-loan balance (€390 versus €360 respectively).