European Defence: The New ‘Holy Grail’ of European Integration?

In the classic Western The Magnificent Seven, seven wandering gun-slingers join forces to protect the inhabitants of a remote village from a cruel bandit and his gang. The film glorifies the sense of duty that exists among even outcasts and outlaws, but also the agonizing quest for a purpose worth living and dying for. The film highlights the different motives that can bring highly diverse personalities together for a just and common cause. Each of the seven has their own reason to join the group, whether it be money, action, recognition or simply redemption for past crimes and guilt.

What has this film to do with European defence integration? If security and defence integration is the Holy Grail of the next European narrative, taking the place of economic integration, which has reached its limits, then it is important to identify both the capacity and willingness of the EU member-states to move forward and strengthen their acquis in this field. Engagement in the existing military cooperation schemes and the concomitant commitments undertaken, reveal national positions and intentions and are useful as proxy indicators for the operationalization of the member-states’ attitudes toward enhanced defence integration. This policy brief compiles the main insights of a broader study prepared by the authors for ELIAMEP.

We examine seven EU countries (‘the Magnificent Seven’) with quite different features, taking stock of their contributions and accounting for their underlying motives. First and foremost, we look at the Franco-German axis, without which the discussion on defence integration is meaningless both politically and substantially. The Southern rim countries are also included, namely Italy, Spain, Portugal, and Greece. This is not only because they face similar security challenges stemming from their geographical proximity to areas of significant regional instability – Portugal to a lesser extent that the other three, and Greece with the additional external constraint of Turkish expansionism and revisionism. They also traditionally share an integrationist view on the future of the EU and have repeatedly joined the demandeurs’ camp on issues of political and foreign policy integration. Poland is the seventh country in our study. It is the largest of the bloc of states that joined after 2004 and often considers and presents itself as the political leader of the countries in the region. The size of the Polish military, its significant security preoccupations with Russia, as well as its aspirations to play a leading political role in the European integration process render the country a potentially influential actor in the process of deepening defence cooperation further.

Our comparative analysis is structured along two basic axes. Both are resource-oriented, with the first focused on economic and financial resources (i.e. the budgetary dimension) and the second on human (and institutional) resources (i.e. the participatory dimension in the existing collaborative EU military configurations). Starting with the former, we begin by examining the military expenditure of the seven countries, breaking it down into four categories to enable a more structured and insightful analysis. These categories comprise personnel cost, equipment, infrastructure, and other expenditure. Moving on to the latter dimension, we present the countries’ level of participation in three existing forms of EU defence cooperation, namely the EU Battlegroups, contributions to the EU military missions and operations, and current engagement in PESCO projects.

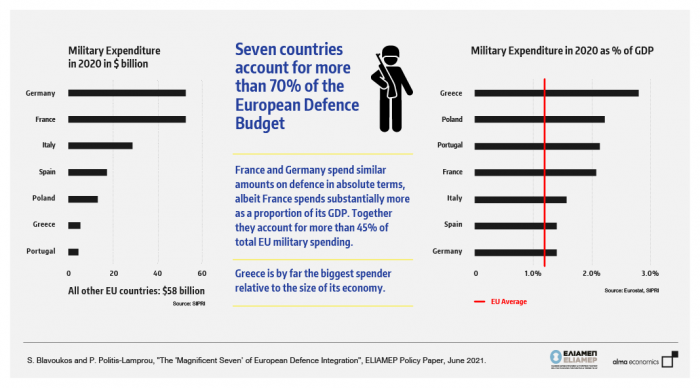

Military expenditure

One of the main criticisms leveled by the United States at its European and NATO allies is that they have been systematically freeriding underneath the American security umbrella while investing domestically on ‘butter’ rather than ‘guns’. Such complaints and pressures, expressed and exerted by several US presidents over the years led the NATO allies to agree at the 2014 Wales summit on the threshold of 2 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) which each member of the alliance should allocate to military expenditure. Still, very few EU states have reached this target.

The ‘Magnificent Seven’ convey a mixed picture: Greece consistently spends more in relative terms than any other of the six countries (2.63% in average), followed by France, Portugal, and Poland, which are close but not above the 2% NATO threshold. At the other end of the spectrum, Spain and Italy spend considerably less, with Germany occupying the last place in the list. For 2020, the economic crisis brought on by the pandemic and the subsequent reduction in national GDPs globally led to a large nominal increase in military expenditure as a GDP ratio in all the countries under examination. This is worth stressing to avoid jumping to conclusions on the basis of the 2020 figures. Moving away from this macroscopic overview and zooming in to the sub-items of the defence budgets, a more nuanced picture emerges.

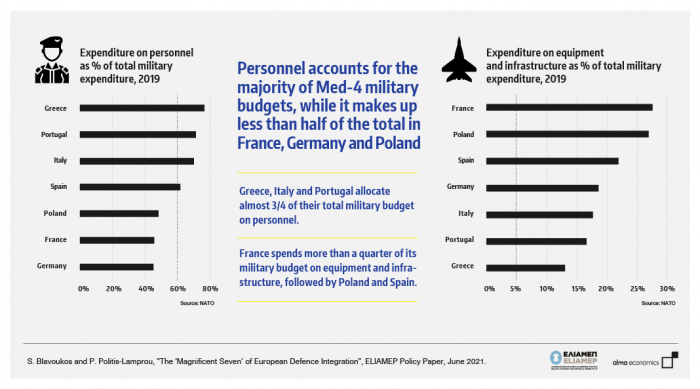

France is the undisputed leader of the group. France is following the broader trend towards leaner, smarter and more professional armies that can swiftly and effectively intervene in various types of crises around the world. For this reason, since 2008, France has engaged in a significant downsizing of its armed forces but also a considerable reprioritization of the needs, as evidenced by the announcement of the French President, Emmanuel Macron, of 6.000 new hirings mainly in intelligence analysis and cyber security. France has kept investing on its operational capabilities. The military planning law for the period 2019–2025 envisages the upgrading of the existing conventional and nuclear equipment and weapons, while allowing for greater investment in research and development. Finally, France has redirected a considerable amount of financial resources to cover the cost of military missions after the terrorist attacks on French and European ground, in 2014 and 2015. The extensive mobilization and deployment of the French Armed Forces both abroad in operations against jihadists, as well as domestically to protect the country’s critical infrastructure has come at a considerable financial cost. The French intention to reduce its military presence in Sahel is expected to reduce the share of this budget line.

Compared to France and the other member-states under review, Germany is clearly lagging behind in terms of military expenditure. The reluctance to invest more resources reflects historical and societal concerns but also bureaucratic obstacles that prevent the modernization of the Bundeswehr. The fact that Germany invests much more than the other six states on infrastructure is partially accounted for by the operational costs of NATO’s military bases in German soil. Cybersecurity has emerged as one of the key German priorities, as evidenced by the establishment of the Cybersecurity Innovation Agency, in 2020, with an initial budget of 350 million Euros, to ensure the country’s ‘digital sovereignty’. Overall, according to state officials, including the current Federal Minister of Defence, Germany will meet the NATO 2% of GDP guideline in 2031, at the latest, which explains the incremental increase in the German defence budget in the last four years.

The four Mediterranean countries (Med-4), namely Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain, share two common elements as regards their defence budgets. First, they were significantly hit by the financial turmoil and their painful effort to achieve fiscal consolidation. This is more evident in the ‘equipment and infra-structure’ sub-items, in which all four countries made significant cuts in their military procurement plans during the peak years of the crisis. These items show considerable fluctuation in the last decade, absorbing a large part of the fiscal consolidation pressures. Second, a big part of the defence budget, around 75% for Italy, Greece, and Portugal and about 60% for Spain, is allocated to personnel costs, although these figures were also affected by the economic crisis. Compared to France, Germany, and Poland, in which personnel costs account for about 50% of their defence budgets, this feature entails a very different emphasis on resource allocation.

In Italy, almost 3% of the country’s labor force is classified as military personnel.[1] The 2015 White Paper acknowledged this problematic situation and proposed a significant reduction in both military personnel, especially in the upper echelons of the military hierarchy, and the auxiliary civilian bureaucracy. Furthermore, after 2012, Italy has focused on the modernization of its military by investing in new equipment, research, and technology. Italy is willing to make the most of the opportunities offered at European level to finance armaments, research, and maintenance program, which explains the strong Italian support to the European Defence Fund. Given the costly deployment of Italian forces in areas of interest, especially the Mediterranean, and the deriving burden on the Italian defence budget, Italy is keen on EU orchestrated military missions and operations in the region for financial reasons.

Spain’s defence budget is directed to a significant but not overwhelming extent toward personnel expenditure. Financial resources are also invested by the Spanish government in defence equipment and infrastructure to a larger scale than its Mediterranean partners. The country was severely hit by the financial crisis, especially the domestic defence industry, which suffered major setbacks. In recent years though, a reversal of the downward trend is noticeable, as illustrated by the recent participation in the development of a joint fighter jet project, along with France and Germany, which will cost more than 100 billion euros.

Greece’s defence budget also suffered a major cutback during the crisis, especially in terms of military procurement. The drop in Greece’s military expenditure during this period is estimated to about 40%, which may not be evident at first glimpse in the figures given the plummeting Greek GDP in the same period. The recruiting constraints to the broader public sector affected the armed forces as well and led to a substantial decrease in the size of the military personnel as a percentage of the total labor force (from 1,20% in 2008 to 1% in 2018). The announcement of a large-scale military procurement plan of an estimated worth of 10 billion euros will boost substantially Greece’s operational capacity and the overall defence budget. This plan owes much to the great escalation of tension with Turkey in 2020.

In Portugal, the economic crisis accelerated structural reforms in the military, including a decrease in the Portuguese Armed Forces’ personnel by approximately 15.000 during 2009-2019, and a reduction in the personnel expenditure as percentage of the overall defence budget. In addition to this, Portugal focused on maintenance in order to extend the operational life of the existing military equipment acquired before the crisis.

Poland engaged in the early 2000s in a large-scale program of restructuring and technical modernization of its Armed Forces, with a legally binding obligation of the Polish government to spend 1,95% of the country’s GDP in defence and at least 20% of this expenditure to be invested in military procurement and modernization. In 2015, a new program reinstated this commitment, which brings Poland very close to NATO’s threshold. Besides the operational needs to modernize the obsolete equipment of the Soviet era and the country’s security concerns vis-à-vis Russia, the political semantics of these two programs are hard to miss. Poland is (self-)portrayed as the best pupil in the class of Central and Eastern European states that have joined NATO. Poland abolished the compulsory military service, in 2008, which decreased the operational costs but also the percentage of the labor force in the armed forces. However, following the establishment of a new corps, the Territorial Defence Forces, in 2016, with an estimated figure of 35.000 troops, the personnel expenditure rose sharply to approximately 50%.

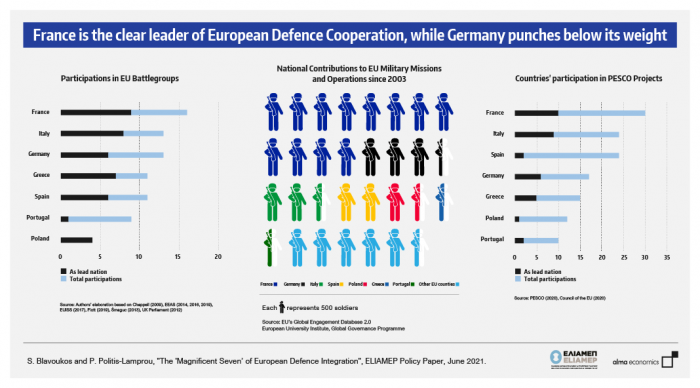

EU Forms of Military Cooperation

Over the years the EU has launched some forms of military cooperation, most notably the EU Battlegroups (EUBGs), the Military Operations, and the PESCO projects. These forms have quite different institutional and political rationale but the participation of member-states in them can be used as a proxy for their willingness to engage more closely in enhanced forms of EU-induced defence cooperation.

France is clearly the leader in these forms of military cooperation schemes. Although the EUBGs evolved in ‘an army in paper’ that has never been deployed or mobilized, still, the French role is indisputable, participating in sixteen and leading nine of them. In terms of the EU military missions, France contributes more than 40% of the overall EU forces deployed in the field and about 85% of the European forces in missions in Africa and the Middle East. As far as PESCO is concerned, France is the country with the most extensive participation in PESCO projects, joining thirty of the forty-six and leading ten of them, with particular emphasis on the development of joint capabilities. France has been calling for a more effective funding mechanism to support these forms of cooperation. France has been one of the top contributors to the Athena mechanism covering fifteen percent of its total budget. This explains why it has put pressure consistently on other EU countries to apply the burden sharing principle, arguing that countries with significant contribution in personnel should shoulder a smaller financial burden.

However, France is not totally satisfied with the current functioning and evolution of PESCO. According to the French views, cooperation should not be inclusive but should rather be limited to member-states with a high technological and military potential. This more elitist approach would lead to the nucleus of a European Army. The great heterogeneity of participating member-states and the currently dysfunctional modus operandi of PESCO almost nullifies the added value of the venture, according to the French side. This is an area of conflict with Germany, which is concerned with the negative spillover of exclusive differentiated integration that would marginalize countries willing but not capable of participating. In that respect, France focuses more on the operational dimension of PESCO, whereas Germany emphasizes its political connotations. Given this divergence of views, France put forward, in 2018, the European Intervention Initiative (EII), which evolves outside the EU framework and comprises thirteen EU member-states and Norway. Although the French side – and the EU High Representative- have stated that this initiative is not competing with PESCO but rather complementing it, the political signaling is clear: France is looking for a leaner, more effective, and more ambitious framework of defence cooperation and PESCO does not currently meet the country’s expectations.

Germany’s overall engagement in the existing defence cooperation schemes is modest. It participates in thirteen Battlegroups and as a lead nation in six of them. However, it is interesting to note that Germany has not formed a unilateral Battlegroup, in contrast to France, Italy, and the United Kingdom (in the pre-Brexit era), but has always joined multinational efforts. In terms of the EU Military Operations, Germany contributes only twelve percent of the total number of deployed armed forces but one fifth of the overall Athena budget. The 2020 German Presidency orchestrated the upgrade to the European Peace Facility (EPF), which takes over the role of the Athena Mechanism, coming closer to the French views on the financing of the EU military missions. As regards PESCO projects, Germany participates in seventeen in total and leads six of them. Germany prefers those projects with a less clearly-defined military identity—the European Medical Command, for example, the Geo‐meteorological and Oceanographic (GeoMETOC) Support Coordination Element (GMSCE), the Cyber and Information Domain Coordination Centre (CIDCC), or the Network of logistic Hubs in Europe and support to Operations.

Italy participates in thirteen Battlegroups and leads eight, two more than Germany. Italy calls for more easily deployable and capable EUBGs but goes even further adhering to a “joint permanent European Multinational Force (EMF)” and permanent EU military Headquarters. The country has been the driving force behind operations in the Mediterranean (SOPHIA and IRINI) but has also joined others in the Balkans and Somalia. Italy -together with Spain- is the second more active country in PESCO projects. It has joined twenty-four projects with emphasis on military research and development-intensive projects that can lead to economies of scale in the production of competitive weaponry exported to the global market. Italy prefers cooperation in small groups of countries to ensure high homogeneity and interoperability of developing systems. The EDF should aim to finance ambitious projects whose implementation in a national or in a bilateral context is hard to achieve, like, for example, the European Patrol Corvette (EPC). In general, Rome sees the PESCO projects and the EDF as an enormous opportunity to further develop its capabilities and keep alive its domestic defence industry.

Spain has joined eleven EUBGs and takes the lead in six of them. It participates in almost all EU military actions and intends to upgrade such participation, at least judging from the effort made to take over the Operational Headquarter for Operation ATALANTA, after Brexit. In terms of PESCO, Spain was one of the keen supporters of the awakening of PESCO and co-authored (along with France, Germany and Italy) the letter addressed to the then HR/VP, Federica Mogherini, that kicked off the discussion on PESCO. The significant Spanish participation in the PESCO projects mainly concentrates on the development of joint capabilities, which alludes to the Spanish intention to support through the European Defence Fund its domestic defence industry that was severely hit by the economic crisis.

Greece has joined eleven Battlegroups and acts as lead nation in seven of them, not least with a view to strengthen cooperation with the country’s Balkan and Mediterranean partners. For example, Greece is the lead nation in the HELBROC Battlegroup, which brings together six countries (Greece, Cyprus, Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, and Serbia) and joins every five years approximately the Spanish-Italian Amphibious Battlegroup. At the same time, the Greek participates in the EU military operations in the Balkans and Somalia, strengthening the country’s stabilizing role in the neighborhood and catering for the smooth operation of the main sea trade routes in accordance with the economic interests of the Greek shipping industry. In terms of PESCO, Greece has a relatively small participation in total number, but it leads one third of the projects it has joined, with emphasis in naval cooperation schemes. The country is ambivalent with regards to the participation of NATO countries in PESCO projects. It would naturally welcome the American presence but not the Turkish one. Hence, Greece was quite satisfied with the 2020 Council Decision that third countries can join only after an invitation by all the countries participating in a project and on an ad hoc basis of evaluation and assessment that will be unanimously decided.

Portugal participates in nine Battlegroups but leads only one. It prefers to participate in EUBGs with at least three more partners to avoid a possible Spanish predominance that could lead to the potential deployment of the Portuguese Armed Forces in areas with no interest for the country. It has a rather timid participation in the EU military missions, with only almost half of Greece’s deployed forces, with substantial presence in two operations mainly, the ongoing one in Bosnia-Herzegovina and the concluded one in Congo (2006). Still, its share in the EU personnel in both operations is very small, only 3.5% and 2.5% respectively. Finally, in terms of PESCO, Portugal participates in a relatively small number of projects, only ten, aiming towards the buildup of a stronger domestic industrial base that can take advantage of the EDF financial opportunities.

Last but not least, Poland has joined only four Battlegroups but always as a lead nation. Thus, the Polish participation is not particularly impressive overall, but it is very targeted, as illustrated by the Visegrád Battlegroup (V4 EU Battlegroup), in which Poland participates with personnel contributions up to 50% and taking over most of its operational costs. Poland contributes rather timidly in economic terms at the Athena mechanism, with approximately 3%, but has been supportive of a broader economic burden sharing, including the transportation cost of the deployed units. Its personnel contribution to the EU military operations is more substantial. Poland took part in the EU military operations, even before becoming officially member, with Polish troops being present in the EU Military Mission CONCORDIA and one year later in the EUFOR ALTHEA/BiH. Poland has been particularly interested in the Balkans, mainly because it is concerned with the destabilizing potential of the region. Such a potential can have a domino effect on the security preoccupations of all countries at the EU eastern flank, including Russia, with dire impact on EU-Russian relations. At the same time, such an active involvement in the Balkans testifies to the broader political aspirations of Poland, especially in view of a further enlargement of the EU with the countries of the Western Balkans. Poland is very active also in Africa, with three fourths of the Polish troops being deployed in the EU military operations there. This is a conscious decision by Poland, which supports the strategic choice of the country to expand its general presence in the African continent, including stronger economic and trade cooperation with many African states. Poland has a rather limited presence in PESCO with twelve participations and only one as the lead nation. It is particularly interested in the capabilities’ activation projects, including the ‘Military Mobility’ (or ‘Military Schengen’) one. A similar NATO-based program has met several legal obstacles and has not progressed far. Poland embraces the EU initiative and puts it forward to illustrate the complementary and non-antagonistic nature of the EU-NATO relationship in the security domain. The Polish participation in PESCO was sealed only after a formal letter by the Polish Ministers of Foreign Affairs and Defence was addressed to the High Representative stating NATO’s supremacy and urging the EU to take greater interest in Eastern Europe.

‘The Magnificent Seven’: Key Insights

Bringing together the insights of the previous sections, we can create the profile of the ‘Magnificent Seven’ vis-à-vis European defence integration and classify them in -overlapping- clusters along four axes: political aspirations, economic situation, geography, and relations with NATO.

Starting with political aspirations, defence integration goes hand in hand with political integration. Participating actively in the existing forms of cooperation indicates the political willingness of countries to move beyond the existing status quo. However, it can also signify a country’s intention to be considered part of the political vanguard of the European integration process. France’s pushing for additional defence collaboration is consistent with the country’s political role in the European integration process. For its part, Germany has joined the launched schemes, but rather hesitantly, since defence integration is not part of the country’s traditional agenda. This obviously owes much to historical memories, an anti-militarist legacy, constitutional constraints, and the strong societal reluctance to resort to the use of force to resolve international crises. For member-states like Italy and Spain joining these schemes is proof of their status and an indication of their intention and desire to belong to the political inner circle of the European integration process. Poland does not hide its political aspirations to lead the Visegrád group and establish itself as an influential political actor in the European integration process. Greece in the wake of a long period of turbulent relations with the EU during the financial crisis seeks to demonstrate and promote its European credentials by rhetorical adherence to, and active participation in, these schemes. As a mid-range country, it is more interested in not being left behind or concerned about not being able to capitalize on the security enhancing benefits of closer cooperation, should it go ahead more dynamically. Portugal’s participation is also largely motivated by its broader political support for, and embracing of, the European integration process and its intention to become part of the European core.

As far as the economic situation is concerned, budgetary constraints in recession-torn countries, such as the Southern countries hit by the economic crisis, make it difficult to support large-scale military engagements. This undermines closer security cooperation, since willing member states that could form the necessary ‘critical mass’ and provide the impetus for further defence integration are unable to deliver on their political promises or commitments.

In terms of the third axis, simply put, ‘It’s the geography, stupid!’ France, as a global power with interests far from the European continent, has grasped the opportunity to project its power while avoiding criticism for neo-colonialism. This is evidenced by the extensive presence of French troops in EU military operations in and around the francophone zone, while the country’s interests in the Mediterranean basin have, of course, not been neglected. Similarly, those EU member-states that are surrounded by or situated close to sources or regions of instability are keener and more willing to participate in any scheme that addresses their security concerns, even partially or illusively. The Med-4 are very active for precisely this reason. Given that Greece has the additional concern of Turkey, the country cherishes any security-enhancing initiative. Spain seeks to consolidate its presence and influence in its close neighborhood and protect its economic interests with a special focus on Africa. The same holds for Portugal which seeks to capitalize on the existing CSDP cooperation to consolidate its political position in the Lusophone world. Although it is facing security challenges of a different sort, Poland is also in favor of such cooperative formats, as long as they do not jeopardize the country’s relationship with NATO and the US.

Finally, the elephant in the room is NATO and how these EU initiatives relate to it. France has been an ardent supporter of greater EU strategic autonomy. Both Poland and Greece must perform delicate balancing acts, because the US is a fundamental parameter in their security functions. Greece is forced to follow a prudent security portfolio diversification, adhering to the far reaching perspective of European defence without alienating the American factor. Poland is very much worried by the ‘Asian pivot’ of the US, which has increased the historical insecurity syndrome of the country. Portugal is also seeking to balance its long-held Atlanticist orientation with political adherence to the European integration process, as mentioned above. It therefore comes as no surprise that the country is keen on highlighting the complementary and potentially symbiotic nature of NATO and EU in the security realm. Germany has adopted a very cautious approach. Striving to leave the status quo intact, it also seeks to avoid alienating the US while simultaneously accommodating the French vision of EU strategic autonomy. Germany has succeeded in integrating all willing EU member states into the schemes and allowing the ad hoc accession of third -NATO members- countries in them under specific conditions. The latter was a conscious attempt to show the country’s NATO allegiance and convey the image of PESCO as a non-antagonistic scheme of defence cooperation. For their part, Spain and Italy have signaled their readiness to allow the EU a greater footing in the light of the benefits of such cooperation. Italy firmly believes that the evolution of PESCO does not harm the transatlantic defence cooperation and strongly supports third-state participation in PESCO.

Conclusions: the ‘Fiddlers on the Roof’ of European Defence Integration

In the classic musical The Fiddler on the Roof, the main character, Tevye, preaches about the life-long act of balancing conflicting needs and wills. Every one of the ‘Magnificent Seven’ is to some extent a ‘fiddler on the roof’ in the European defence integration process. Some are trying to find the right level of engagement to upgrade their political status within the European integration process without overcommitting. Others are striving to strike a balance between European security concerns and their national security concerns that are currently better addressed by NATO. In practice, this means that they need to embrace European security and defence integration without alienating the United States. Finally, a few member-states are trying to navigate between the Scylla of financial consolidation and fiscal prudence and the Charybdis of a turbulent region that forces them to invest more in ‘guns’ than ‘butter’. Even France, an ardent and unequivocal supporter of European defence integration, faces significant dilemmas given that the existing schemes of defence cooperation have failed to date to evolve fully in line with its terms and views.

France is the indisputable leader of the process, although it is not entirely happy with its pace and format. That it would welcome more flexible and functional schemes is clear from the French-inspired European Intervention Initiative set out in 2018. The key question for the future development of the process is whether France really is seeking credible alternatives, or whether such initiatives have been put in place primarily to put pressure on its European partners to embrace the French view and terms of defence integration.

Germany lags behind the other member-states, given its economic and political status and might. This is unsurprising, given the multiple and contradictory preoccupations of German foreign policy and its historical legacy. Germany is one of the indisputable leaders of the European integration process in both economic and political terms, so it would be reasonable to expect the country to push for defence integration along with France. However, Germany’s security is simultaneously bound up to a considerable extent with the US and with NATO. Thus, while on the one hand Germany is rhetorically committed to closer European military cooperation so as not to upset the Franco-German axis, on the other it has also to entertain American concerns about the potential autonomisation of the European defence initiatives. With great might comes great responsibility, and Germany cannot keep on juggling these two balls into perpetuity. The main question for Germany is whether the time has come to choose sides, or whether the country can still afford to remain passive in what may evolve into the new overarching narrative of the European integration process.

The Mediterranean-4 share a geographical proximity to highly unstable regions. They also share a common view of the need to enhance the political dimension of the integration process to include foreign and security policy. For Italy and Spain, active participation entails a clear signaling of their aspirations to belong to the elite leading the process, while for Greece and Portugal, it is an indication of their political intent to join the inner group of EU member-states. Greece is also one of the few EU countries that faces a clear security challenge from a neighboring state. This further reinforces Greek support for military cooperation, not because it alleviates the country’s security concerns, but rather in light of its future potential, if there is any. All these countries are also NATO members, however, and they are not willing to relinquish the American security umbrella. In other words, the Med-4 face the same dilemma, more or less, as Germany. Their main preoccupation at the moment is how much ‘EU defence integration’ NATO will tolerate, so they will not be forced to choose sides. Making the former option viable and substantial entails a great leap forward in sovereignty-sharing in the field of security and defence. Hence, a related question is how much further the Med-4 are currently willing to go in this respect. At the same time, all four Mediterranean countries have undergone a painful process of fiscal consolidation. Even if the worse phase of this crisis seems to be over, its marks remain visible. Therefore, in addition to political and security considerations, the need for fiscal prudence also conditions the extent of the Med-4’s commitment to European defence integration.

Finally, while Poland is clearly prioritizing NATO over the EU at present in the security realm, it has no intention of being left out of the EU military cooperation build up. Its participation in it is very focused on networking with its neighbors in Central and Eastern Europe, thereby reinstating its aspirations to regional political leadership. The ‘Asian pivot’ of the US may push Poland to seek new security partnerships, in which case the EU may emerge as an enticing alternative, which explains why Poland leaves the door of European defence integration half-open.

[1] The large size of the Italian military personnel is partly due to the two law enforcement agencies with military features: the Carabinieri, which is the fourth branch of the Italian Armed Forces patrolling the interior in coοperation with the police, and the Guardia di Finanza, whose duties are related to financial crimes, but is also entrusted with naval military tasks.