Greece has so far failed to shift its production structure towards more complex, high value-added activities, incorporating knowledge-intensive practices. Given the country’s low performance in innovation and knowledge diffusion relative to EU peers, we focus on two specific problem areas of Greek industry: skills and management practices. First, we provide an in-depth look at skills indicators to identify the scope for action, particularly in addressing mismatch. Second, we use firm-level data from the World Management Survey to give an overview of management practices in Greek industry and explore the quality of these practices and their association with productivity. We have two novel findings: first, we document that Greece has the highest overskilling for professional occupations in the OECD; second, we show that Greek firms do best in areas requiring unitary decision making, and worst in areas requiring teamwork and synergies. We complement our analysis with data from a new survey and examine structural characteristics of innovation and technology adoption. The collection of our empirical findings provides valuable input into concrete policy proposals to increase productivity in Greek manufacturing.

Read here in pdf the Policy paper by Sofia Anyfantaki, Research Economist, Bank of Greece, Economic Analysis and Research Department; Yannis Caloghirou, Professor Εmeritus, National Technical University of Athens, School of Chemical Engineering; Konstantinos Dellis, Adjunct Lecturer, University of Piraeus, Department of Economics; Aikaterini Karadimitropoulou, Assistant Professor, University of Piraeus, Department of Economics and Filippos Petroulakis, Research Economist, Bank of Greece, Economic Analysis and Research Department.

| Disclaimer: This project is part of the Hellenic Observatory Research Calls Programme 2020, funded by the A.C. Laskaridis Charitable Foundation and Dr Vassili G. Apostolopoulos. The original paper has been published with the title “Skills, management practices and technology adoption in Greek manufacturing firms” (Bank of Greece Economic Bulletin, Issue 55, Article 1). The views expressed in this article are of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Greece. The authors are responsible for any errors or omissions. |

Introduction

Greece remains a laggard among peer countries in various domains that are critical for sustainable long-term growth: the production structure remains largely unchanged and domestic output still lacks sufficient knowledge-intensive characteristics.

Significant progress has been achieved since the Greek economy suffered one of the deepest and longest recessions of any advanced economy to date. The large twin deficits had been reduced, and the Greek economy had gradually recovered until the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, today the Greek economy continues to face a number of challenges, which constrain its long-term prospects. Greece remains a laggard among peer countries in various domains that are critical for sustainable long-term growth: the production structure remains largely unchanged and domestic output still lacks sufficient knowledge-intensive characteristics. Substantial increase in potential growth is only possible through enhancing capabilities, raising the productivity of existing resources and engaging in innovation.

In this study, we focus on selected but important problem areas of Greek industry. In particular, we focus on skills and management practices, while also providing an in-depth examination of Greek firms’ innovation activity and technological readiness. We review well-known stylised facts and empirically establish new ones. Our goal is to gain a more granular view, so as to identify specific themes for policymakers and stakeholders to target.

Our focus is dictated by both the importance of each topic and the need for improvement. Worker skills and managerial practices are widely recognised as key inputs in modern economies and are the intensive focus of research and policy. Both are key enablers of innovation, the main source of sustainable long-term growth, which heavily relies on advanced knowledge. More generally, the importance of human capital, including the need to efficiently allocate it, is increasing in the digital economy. Yet, Greece scores relatively poorly across a wide range of indicators pertaining to these issues.

In Section 2, we review evidence on the dimensions of the skills gap in Greece to identify the scope for action, particularly in addressing mismatch. Although Greece has internationally competitive rates of educational attainment among OECD countries, the transition from university to the labour market is one of the most difficult (OECD 2020a). This phenomenon is likely related to the extensive skills mismatch, where Greece features at the EU bottom in relevant rankings (Cedefop European skills and jobs survey), a situation made worse by the brain drain caused by the financial crisis. Skills development is a complex endeavour, and persistent skills gaps and mismatches come at economic and social costs, while skills shortages can negatively affect labour productivity and hamper the ability to innovate and adopt technological advances. We establish that Greece has by far the highest professional overskill mismatch in the OECD sample. We then examine empirically the relationship between mismatch and productivity; our results corroborate previous findings that overskilling has a negative effect on labour productivity.

In Section 3, we turn to another important area for action, management practices, a factor empirically established as crucial in explaining differences in productivity between and within countries and sectors (Scur et al., 2021). Management practices have been recognised as akin to a technology (Bloom et al. 2016) and as a key input for innovation and technology absorption (Acemoglu et al. 2007). We find a high dispersion of management practices within the country, suggesting that although there are few leaders in terms of good management practices, the diffusion is quite low. We show that Greek firms perform worst in issues requiring people management, planning, oversight, as well as synergies, dialogue and collaboration. They do best in issues requiring decision-making, possibly by a single individual. We further point to an interesting result: Greek firms exhibit the lowest levels of employee autonomy. Given the high incidence of family-managed firms, this paints the picture of a corporate culture tied around a founder, with little room for talent development and firm decentralisation.

In Section 4, we corroborate our findings using a novel survey of the Greek manufacturing sector. We examine structural characteristics of firms’ innovation activity and digital adoption. We confirm the negative association between firm size in innovation, and well as in adoption of digital technologies, where family ownership is a further problem factor. Even more troubling is the role of family ownership in determining readiness for the fourth industrial revolution.

Finally, in Section 5 we conclude the paper, and use the results of the previous section to provide targeted policy recommendations.

The alignment of skills with job requirements in Greece

Skills indicators

To date, most EU Member States, including Greece, have responded to the challenges posed by different drivers of skills demand by seeking to increase skills supply, notably through raising educational attainment. Notably, Greece has experienced an increase in tertiary education attainment over the last decade: in 2020, 44.2% of adults aged 25-34 had completed tertiary education, against 32.7% in 2010 (OECD 2020a). However, while educational attainment in Greece has increased over time, there are concerns that the education and training system is not sufficiently aligned with labour market needs.

Indeed, a major problem facing the Greek labour market is the relatively large share of low-skilled individuals. Greece had one of the lowest overall scores in the European Skills Index.

Indeed, a major problem facing the Greek labour market is the relatively large share of low-skilled individuals. Greece had one of the lowest overall scores in the European Skills Index (ESI) survey of 2022, only marginally improving its performance relative to 2020 (from 20 to 23). The low skills level of the Greek economy means that employers may be unable to fill vacant positions because of skills gaps or shortages (lack of employees with suitable skills or qualifications), making this mismatch between the supply of and demand for skills a significant impediment to potential growth.

However, mismatch may also characterise existing employment relationships. On-the-job mismatch refers to situations where there are discrepancies between the skills and qualifications of employees and the skills/qualification requirements of their job. These discrepancies may also arise due to differences in the quality of skills developed through training or skills depreciation over the lifecycle and changes in skills demands. Labour market mismatch refers hence to situations where it is possible to shift workers across jobs and increase productivity, by improving the efficiency of resource allocation. An efficient allocation of workers across tasks is particularly important when the aggregate skills supply is relatively limited, as is the case for Greece.

The most commonly used measure of mismatch is overskilling (McGuinness and Wooden 2009). Data from PIACC suggest that Greece suffers from a high level of mismatch between the skills workers possess and those demanded of their jobs. Around 28% of workers are more proficient in literacy than their job requires (overskilled), the largest proportion across all participating countries/economies and much higher than the OECD average of 10.8%. At the same time, around 7% of workers are less proficient than required for their job (compared with the OECD average of 3.8%) and can be considered underskilled. Mismatch is damaging for workers, as it likely entails lower job satisfaction and a wage penalty, given that overskilled workers earn lower wages than workers with similar proficiency but who are well-matched with their jobs (Adalet McGowan and Andrews 2015). Furthermore, firms may also incur higher training and hiring costs, in addition to reduced productivity and growth potential.

Skills mismatch and labour productivity

In line with theoretical predictions, mismatch has been shown to be significantly negatively related to labour productivity. Adalet McGowan and Andrews (2015) argue that while hiring an overskilled worker may be beneficial to a firm, it may have negative consequences on the economy if skilled labour is trapped in unproductive firms. Mismatch can also impact average within-firm growth, since not only is the productivity of the marginal worker higher in more productive firms, but these firms can also grow faster if resources are reallocated towards them (Decker et al. 2017). In a well-functioning economy, resources would flow to more productive uses, resulting in a positive allocative efficiency term for the more productive economies. In fact, research has shown that differences in allocative efficiency are important in explaining differences in aggregate productivity across countries (Bartelsman et al. 2013; Hsieh and Klenow 2009).

We use data from the OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC) to more precisely examine why Greece performs so poorly. Overskilled workers are defined as those whose proficiency score is higher than that corresponding to the 95th percentile of self-reported well-matched workers – workers who neither feel they have the skills to perform a more demanding job nor feel they need further training in order to be able to perform their current jobs satisfactorily – in their country and occupation. Underskilled workers instead are those whose proficiency score is lower than that corresponding to the 5th percentile of self-reported well-matched workers in their country and occupation. We distinguish between highly skilled (“professional”) jobs and all other jobs. The professional category includes occupations in ISCO occupational groups 1 to 3, and we group all other categories together. Literacy proficiency is our proxy for skills, as per common practice.

Greece has by far the highest professional overskill mismatch (i.e. those working in highly skilled jobs are more proficient in literacy than their job requires) compared with all other countries in the sample. Most surprisingly, while in virtually all countries overskill mismatch is much lower for professional occupations than for lower-skilled jobs, the opposite holds for Greece.

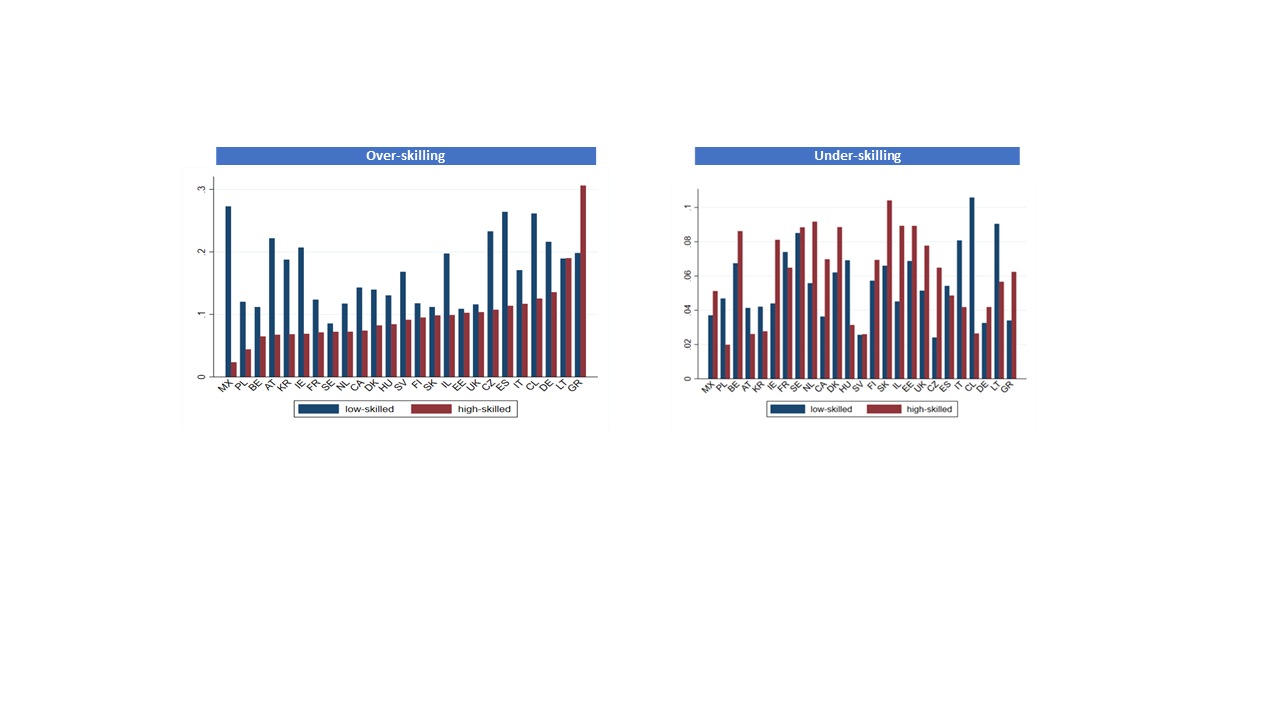

Figure 1 shows that Greece has by far the highest professional overskill mismatch (i.e. those working in highly skilled jobs are more proficient in literacy than their job requires) compared with all other countries in the sample. Most surprisingly, while in virtually all countries overskill mismatch is much lower for professional occupations than for lower-skilled jobs, the opposite holds for Greece. Even for lower-skilled jobs, overskill mismatch in Greece is high compared with other EU countries, although it is much closer to the sample average.[1]

Figure 1 – Skills mismatch for high and low skilled occupations

Note: Overskill (underskill) workers are those who proficiency score is higher (lower) than that corresponding to the 95th (5th) percentile of self-reported well-matched workers.

Source: PIAAC

Given the above evidence of high mismatch in professional occupations in Greece, we now turn to examining the importance of overskill mismatch in professional occupations relative to others. There are no conclusive results in the literature as to whether mismatch in professional jobs is more detrimental to productivity than overall mismatch. In principle, professional jobs are knowledge-intensive and combine high levels of on-the-job learning and match-specific human capital. For example, software developers or chemical engineers require a substantial amount of job-specific training, while their marginal productivity can vary widely across firms, due to the various complementarities involved in these jobs. Moreover, if the supply of professional skills is lower relative to other skills, then search costs for finding or replacing workers for these positions will be higher than for positions requiring less formal training. Skills shortages may also be more binding for highly skilled occupations. Finally, discrimination is expected to be more important for professional occupations.[2]

We follow Adalet McGowan and Andrews (2015) and split aggregate productivity[3] in each sector into a within-firm component and an allocative efficiency component. If more productive firms are larger, the allocative efficiency term is positive and indicates that resources flow to their more productive uses. We then estimate the effect of mismatch on productivity through linear regression models, separately for the three productivity measures (aggregate sectoral, allocative efficiency and average firm) on under- and overskill mismatch indicators at the sectoral level. We find that a one standard-deviation increase in overskilling, at the expense of well-matched workers, holding constant the share of underskilled workers, reduces weighted sectoral productivity by almost 10%.

Overall, the results corroborate the findings of Adalet McGowan and Andrews (2015): overskilling has a negative effect on productivity. Any differences in our estimation results could be attributed to the fact that productivity data cover the period during and after the Global Financial Crisis, unlike Adalet McGowan and Andrews (2015). In any case, regressions are only meant to be indicative, given the small cell sizes especially for the professional occupations. But the upshot is that overskill mismatch plays an important role for productivity, and overskilling in professional occupations, where Greece scores especially badly, is a major drag.

Management practices

Greece in an international context

Management is now recognised as a key driver of growth. Bloom and Van Reenen (2007) found that higher management scores are positively and significantly associated with higher productivity and various aspects of higher firm performance. Further work has shown that well-managed firms tend to imply better work‐life balance and better facilities for workers (Bloom et al. 2009), are more energy efficient (Bloom et al., 2010), have better performance (Bloom et al., 2013) and substantially higher productivity (Bloom et al., 2012).

The quality of management practices in Greece is highly uneven. The high dispersion of management practices, together with a low average score, could give credence to the argument of little diffusion of good practices from leaders to laggards.

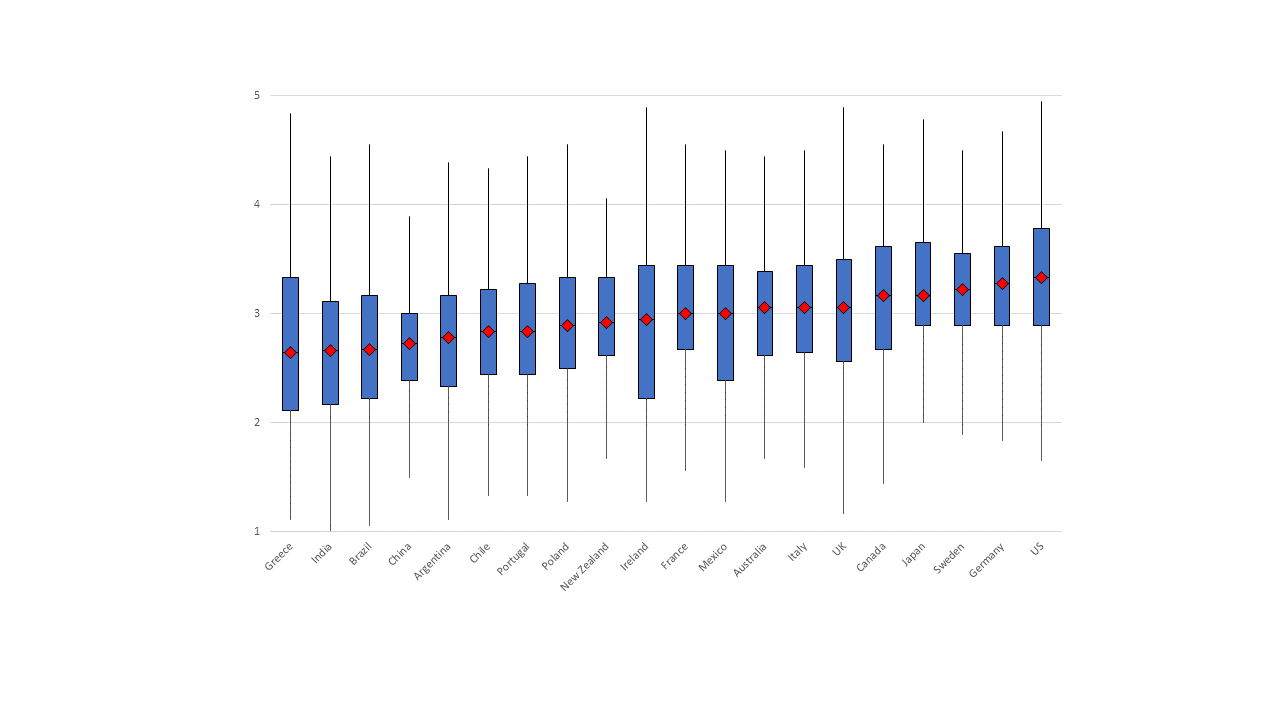

Figure 2 shows average management scores across advanced economies using data from the World Management Survey (WMS), a large, internationally comparable management practices dataset (Bloom and Van Reenen 2007). Greece scores last among other OECD countries. Moreover, the quality of management practices in Greece is highly uneven. The high dispersion of management practices, together with a low average score, could give credence to the argument of little diffusion of good practices from leaders to laggards. The dispersion of management practices bears a clear similarity to the dispersion of productivity. A rich literature has documented that the dispersion of productivity is indicative of low reallocation and technology diffusion, and a key factor behind cross-country differences in productivity (Andrews et al. 2018; Decker et al. 2020). Bloom et al. (2019) show that differences in management practices in the United Sates account for a similar (or larger) share of the variation in productivity as ICT, human capital and R&D. Indeed, Greece has been shown to have one of the largest dispersions in productivity in Europe (Gorodnichenko et al. 2018), which is suggestive evidence of the importance of management.

Figure 2: Management scores across countries

Note: Management scores, from 1 (worst practice) to 5 (best practice). Averages are calculated across all firms within each country.

Source: World Management Survey (WMS)

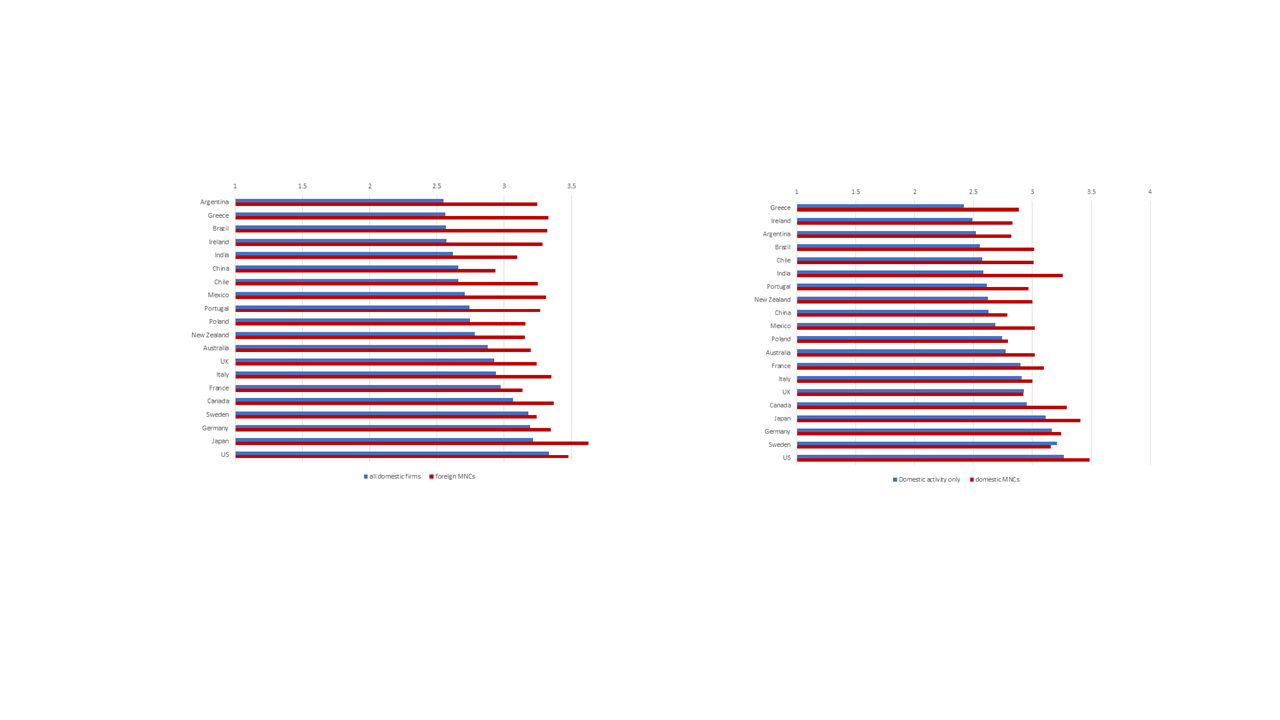

Delving into the drivers of dispersion in management practices in Greece, two features stand out. First, Greece has the largest gap in management practices between domestic firms and foreign multinationals operating in Greece (Figure 3). More strikingly, these foreign multinational firms tend to score very well compared with multinationals in other countries. For example, a branch of a multinational firm domiciled in the United States and operating in Greece is managed as well as the branch of the same multinational operating in Sweden or France. This is both surprising and encouraging since it indicates that, despite the perverse regulatory and macroeconomic circumstances in the Greek economy, firms can find ways to be well‐managed and hence productive (Genakos 2018).

Greece also has the largest gap among advanced economies between domestic firms active in Greece only and domestic firms with overseas operations. Put another way, the productivity gap between domestic companies with overseas activities and those without is the largest in advanced economies.

Second, Greece also has the largest gap among advanced economies between domestic firms active in Greece only and domestic firms with overseas operations. Put another way, the productivity gap between domestic companies with overseas activities and those without is the largest in advanced economies. The direction of causality here is unclear. On the one hand, only the most productive companies have overseas activities, and to the extent that more productive companies are better-managed, we would expect the gap to be large in a relatively low-productivity economy.[4] On the other hand, it is possible that foreign affiliates of Greek firms operating in countries with better management practices benefit from exposure to such practices, which they then import to Greece; such spillovers are common with knowledge-intensive inputs, such as management (Fons-Rosen et al. 2017). Either way, it is indicative of deep deficiencies in the management of Greek firms, but also underscores the potential for improvement. Similar conclusions are drawn even if we separate overall management score into its broad categories: lean operations; monitoring and target-setting; and talent management. Greece is consistently ranked near the bottom of the distribution across all three categories.

Figure 3: Multinationals vs domestic firms

Source: World Management Survey (WMS).

Table 1 shows the categories where Greece has the best and the worst performance, relative to the average of advanced economies. All five of the worst performing categories are broadly related to monitoring and talent management. Greek firms are lacking in performance tracking, clarity and comparability of goals, as well as process documentation, through which these goals can be achieved, and they also fail in developing talent and promoting high performers. These are intimately related: managers seem unable to set realistic goals and employ clear measures to gauge performance, which can result in an inability to reward and hence develop talent. These findings align well with common perceptions about human resource practices of Greek firms, as well as other evidence: for example, Greece ranks last among OECD countries in reporting job strain (OECD 2019).

Greek firms do worst in issues requiring people management, planning and oversight, requiring synergies, dialogue, and collaboration. They do best in issues requiring decision-making, possibly by a single individual.

On the other hand, Greek firms appear to perform at par with firms in other countries in the scope and appropriateness of lean manufacturing techniques. They also score close to the overall average in talent retention and in creating a distinct employer value proposition (employer attraction). These findings point to an interesting pattern: Greek firms do worst in issues requiring people management, planning and oversight, requiring synergies, dialogue, and collaboration. They do best in issues requiring decision-making, possibly by a single individual.

Table 1: Management scores of Greek firms compared with advanced economy average

| Worst performer | Best performer | ||

| Category | Standard deviation difference from mean | Category | Standard

deviation difference from mean

|

| Performance tracking | -0.5869 | Introducing lean (modern) techniques | -0.0029 |

| Developing talent | -0.5261 | Retaining talent | -0.0101 |

| Clarity of goals and measurement | -0.4574 | Rationale for introducing lean (modern) techniques | -0.0186 |

| Process documentation and continuous improvement | -0.4219 | Creating a distinctive employee value proposition | -0.0393 |

Source: World Management Survey (WMS).

Greek firms also prevent their employees from exercising judgement and discretion, instead requiring them to follow strict rules and procedures, and delegate to senior management.

A potential corollary of this finding is that Greek firms also prevent their employees from exercising judgement and discretion, instead requiring them to follow strict rules and procedures, and delegate to senior management. Such structures can inhibit firm growth, as larger firms require local decision-making and flexibility in responding to shocks.

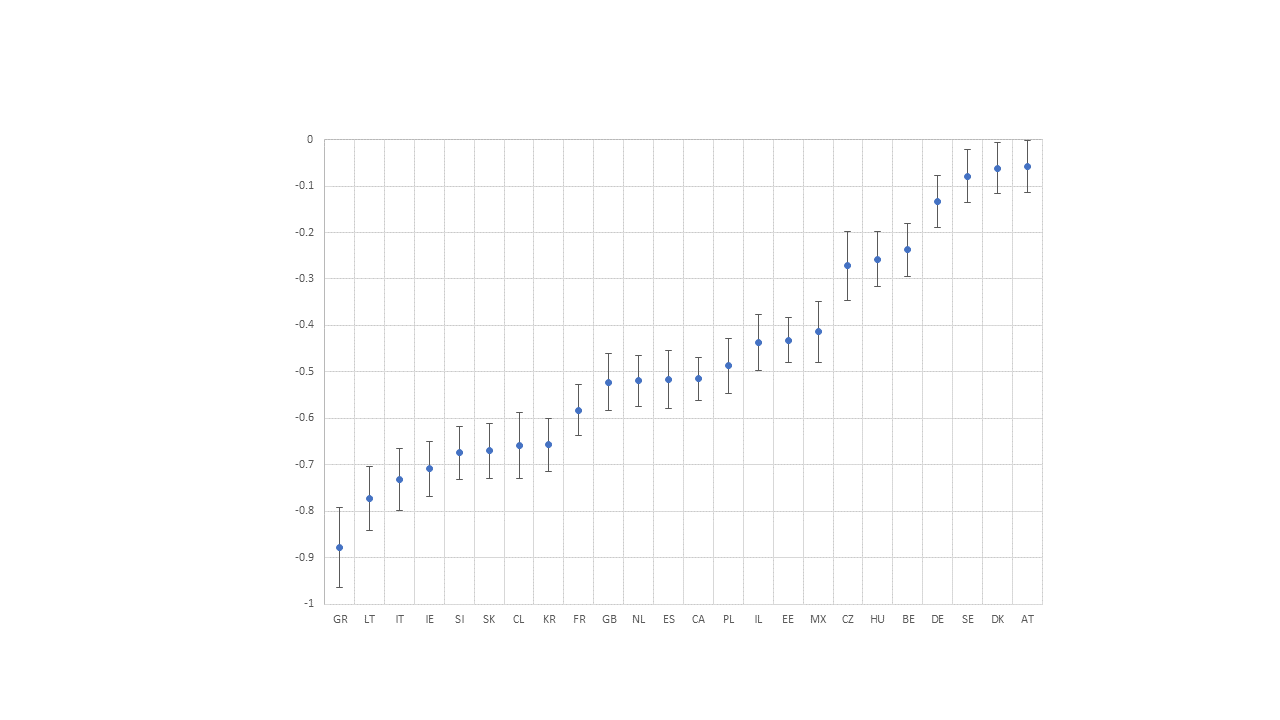

To examine this hypothesis, we augment our analysis with PIACC data on questions about employee autonomy. Employees were asked to define their degree of freedom in choosing and/or changing the sequence, mode and speed of their tasks, and their working hours. Regression analysis of the overall score of employee autonomy on country, firm-size and sector-occupation dummies shows (Figure 4) that Greece scores last, lagging almost one standard deviation below the top (Finland).

Figure 4: Employee autonomy

Note: The Figure shows coefficients (along with 95% confidence intervals) from a regression of the overall score of employee autonomy on country, firm-size and sector-occupation dummies (excluding the self-employed). The coefficients are given in differences relative to the top performer (Finland).

Source: OECD Survey of Adult Skills (PIAAC).

We have provided empirical evidence that Greek managers do best in issues related to decision-making, which may not require any delegation, and worst in issues requiring teamwork and cooperation, while allowing little employee autonomy relative to their peers. These findings are consistent with low levels of trust between firms and workers and could also correspondingly signal little attachment to the job, low accumulation of human capital, and eventually low productivity and wage growth. This can also have considerable consequences for the viability of small firms when, for example, the founder retires, and the succeeding generation shows a weak corporate governance framework and lower managerial quality.

The literature has documented important benefits of decentralised decision-making and high employee autonomy, as well as how lack of trust can impede such arrangements. Bloom et al. (2012) posit that higher social trust facilitates delegation of authority to workers, which can indirectly affect productivity, primarily through its interaction with ICT technology (e.g. higher trust allows autonomous decision-making, which allows better use of ICT). To boot, Greece ranks at the lower end of European countries when it comes to trust.[5] More importantly, decentralisation is a necessary condition to allow firms to grow beyond a certain size. Decentralisation can also help firms withstand shocks. In volatile environments, the value of local knowledge may be more important than the ability of a chief executive to issue centralised decisions (Aghion et al., 2021).

The lack of autonomy also relates to lack of flexibility in work arrangements, a particularly salient feature of the pandemic. Despite the potential risk of moral hazard problems, as employees might abuse their discretion, the literature finds that working-time autonomy improves individual and firm performance (see for example Beckmann (2016) and references therein). Although there is a trade-off between autonomy and close supervision (Aghion and Tirole 1997), some industries have relatively high decentralisation requirements, and low structural levels of autonomy may be detrimental to the development of these industries.

Management practices and labour productivity

Having established some empirical regularities of the management practices of Greek firms, we then examine how they relate to productivity. Clearly establishing the causal effect of how changes in management affect productivity is not possible. Nevertheless, examining the association between measures of management and firm performance in terms of productivity is an important first step in determining the extent to which management practices are economically meaningful. To this end, we merge WMS data for Greece with 2017 Orbis financial data. This yields a dataset of 282 unique firm observations, of which 235 are from the 2014 wave of the WMS and the rest is from the 2006 wave.

Across all measures, we find that better-managed firms are more productive.

Across all measures, we find that better-managed firms are more productive. For the aggregate management score, regression analysis suggests that firms with a one standard-deviation higher average management score have about 15 log points higher labour productivity, a sizeable difference. The relationship between productivity and management is strong across most subcategories of management indicators.

Overall, given the well-established relevance of management for productivity, the above findings are particularly troubling as regards the long-run growth prospects of the Greek economy. Poor management implies a lack of appropriate structure to take advantage of existing human capital, an inability to appreciate the benefits from the adoption of new technologies, techniques and processes, as well as a lower innovation potential. As such, it may be more of a burden in ICT-intensive sectors, given that ICT capital requires a more complex set of inputs beyond just machines and equipment (Bresnahan et al. 2002). In general, the literature has pointed out that the inability of European firms, especially in Southern Europe, to exploit the potential of ICT is an important factor behind lacklustre growth over the past two decades (Pellegrino and Zingales 2017; Schivardi and Schmitz 2020).

Innovation and technology adoption

We use a novel survey on entrepreneurship, technological developments and regulatory change completed in 2019 by the Laboratory of Industrial and Energy Economics – National Technical University of Athens (LIEE/NTUA) and supported by the Hellenic Federation of Enterprises in order to examine structural characteristics of (i) innovative versus non-innovative firms, and (ii) firms that are in the forefront of digital technologies. We focus on the role of size, family firm vs non-family, participation in GVCs and talent management since these have appeared to play an important role for firms’ innovation behaviour.

We briefly present here the main findings (for details see Anyfantaki et al. 2022). We confirm that firm size is indeed an important impediment for product innovation. Somewhat surprisingly though, we find that family firms do not exhibit subpar performance with regards to innovation (controlling for size), although they are substantially less likely to have an in-house R&D department (an indicator of persistent innovation activity). Cohen and Levin (1989) outline some arguments for large firms being more innovative: they can use internal funds to finance the risky R&D activities, they have access to additional sources to finance their innovation activities, they may better exploit economies of scale etc. On the other hand, family firms have the advantage of swifter decision-making, flexibility, and adaptability. Overall, differences between the innovation processes of family versus non-family firms have become an important area of research in the management and economics literature (De Massis, Frattini and Lichtenthaler, 2013).

Greek manufacturing firms appear to perform in general rather poorly concerning usage of Big Data and data analytics as well as the introduction of new business models suitable for online operations e.g. e-commerce and participative platforms.

As for digital technology adoption, according to the survey sample, Greek manufacturing firms appear to perform in general rather poorly concerning usage of Big Data and data analytics as well as the introduction of new business models suitable for online operations e.g. e-commerce and participative platforms. Moreover, controlling for a number of firm performance factors, we show that family firms are significantly less likely to adopt practices associated with the process of digital transformation. Finally, participation in GVCs is positively associated with innovation and adoption of digital technologies. According to the recent empirical literature, stronger participation in GVCs enhances domestic complexity productivity (Gereffi, Humphrey and Sturgeon, 2005; Baldwin, 2016; Taglioni and Winkler, 2016), while establishing linkages in global production networks contributes to knowledge transfer and technology spillovers (Amendolagine, Presbitero, Rabellotti and Sanfilippo, 2019).

Conclusions and Recommendations for policymakers and stakeholders

The collection of our empirical findings provides ample fodder for concrete policy proposals to increase productivity in Greek manufacturing.

First, education, skills and labour market policies should ensure that workers are equipped with the right skills and that businesses can flexibly deploy workers to meet changing labour market needs. The implementation of these policies will help ensure that technology adoption has a positive impact on both productivity and workers. Persistent skills gaps and mismatches come at economic and social costs, while skills constraints can negatively affect labour productivity and hamper the ability to innovate and adopt technological advances. The key message is that the various policies should be closely coordinated and integrated into an intelligent and inclusive industrial policy for both higher and vocational education and training. More precisely, some strategic initiatives should be carefully designed and implemented. We suggest the following:

Policy 1: Establishing and promoting university-industry cooperation schemes. This will help link the needs and problems of manufacturing firms with the valorisation/commercialisation of academic research. This is a clear double dividend: the industry will address skills shortage by tapping and forming/building the exact type of human capital it requires, all the while reducing brain drain. In this context, joint programmes tο pursue diploma theses and industrial doctoral dissertations in fields of common interest should be designed and implemented.

There is an urgent need to invest in human capital before and after entry into the labour market and in particular in upskilling and reskilling, due to the rapid technological and organisational changes.

Policy 2: Maintaining balance between formal education, in-firm training and lifelong learning. The Greek skills development system is characterised by academically-oriented formal education and limited in-firm training and lifelong learning. There is an urgent need to invest in human capital before and after entry into the labour market and in particular in upskilling and reskilling, due to the rapid technological and organisational changes. A balanced mix of training and lifelong learning schemes by large industrial firms, business associations and academic institutions should be launched and funded.

Policy 3: Maintaining balance between formal and tacit curriculum in Greek universities. A variety of joint activities in addition to the formal curriculum could be developed systematically, with a view to strengthening students’ business acumen. Examples are industrial visits, internships for students as a degree requirement, career days, joint workshops dealing with specific industrial problems, mentorship programmes, etc. Such initiatives can reduce the acute problems of adverse selection in job search, as students are unfamiliar with the work environment and the needs of industry before graduation, and thus improve the matching process.

Policy 4: Promoting student networks – as part of the broader university activities – can serve similar goals. In particular, this can include volunteer networks, student groups dealing with issues related to their studies, their scientific discipline, or industry and business evolution, conferences, training summer schools and workshops, and exploration of different career paths.

Upgrading secondary and upper secondary technical-vocational education and training. This is essential to ensure that students’ skills meet the needs of industry.

Policy 5: Upgrading secondary and upper secondary technical-vocational education and training. This is essential to ensure that students’ skills meet the needs of industry. Apprenticeships are required for many trades and can take different forms. The Swedish approach, for instance, involves students completing three-year-long vocational education in upper secondary school, followed by a post-secondary apprenticeship (Fjellström and Kristmansson 2019). Another approach incorporates vocational training directly into upper secondary school through an apprenticeship, along with a carefully established apprenticeship curriculum (to ensure that educational goals are not overlooked). An eclectic approach is warranted, depending on the needs of different sectors.

Second, on the management practices front, we show that Greek firms perform worst in issues requiring team-work, and best in issues requiring decision-making. Furthermore, Greece scores last in terms of employee autonomy. Given the high share of family-owned firms, this points to a corporate culture tied around the founder, leaving little room for talent development and firm decentralisation.

While this is a particularly challenging area to improve, because it would conflict with the inner workings of firms, we suggest the following:

Policy 6: Engaging in changing business culture and management practices in Greek manufacturing firms, i.e. through specific in-firm training programmes, by purchasing external services or by experimenting in new management practices and relevant organisational schemes.

Policy 7: HR departments should focus on the managerial skills of firm employees and the selection processes of managers at different levels.

Dealing in a professional way with the problem of succession in Greek family firms. This is arguably the most difficult, but also the most important task.

Policy 8: Dealing in a professional way with the problem of succession in Greek family firms. This is arguably the most difficult, but also the most important task. A particularly useful model for Greece, taking into account its societal structure, is the German Mittelstand, where family-held firms are typically run by professional managers outside the family.

Policy 9: Promoting joint ventures and other forms of cooperation between professionally organised and managed firms and traditional family-managed firms.

Third, on the innovation and technology adoption front, results show a positive link between firm size and product innovation. In turn, family-owned firms are less likely to have an in-house R&D department and ) adopt practices associated with the process of digital transformation. Both those factors are indicators of persistent innovation activity. Greek firms are also shown to lack usage of Big Data, data analytics and new business models suitable for online operations.

Linking research with innovation and further activating knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship (startups, spinoffs, spinouts and mature firms) as well as corporate entrepreneurship could be a driver for upgrading the innovative capacity of the Greek industrial system.

In this regard, linking research with innovation and further activating knowledge-intensive entrepreneurship (startups, spinoffs, spinouts and mature firms) as well as corporate entrepreneurship could be a driver for upgrading the innovative capacity of the Greek industrial system (Pissarides Commission 2020; LIEE/NTUA 2021). We suggest:

Policy 10: Establishing a bottom-up technology transfer initiative. An especially successful example is the Commission for Technology and Innovation (CTI) in Switzerland, which provides coaching, networking and financial support to academic and private research initiatives, in order to create viable commercial ventures (Arvanitis et al 2013; Beck et al. 2016). The Swiss model is especially attractive for Greece, because it does not feature a leading role for the central government, which only acts in a coordinating capacity, and instead allows for bottom-up initiatives by various actors. As such actions have already started to materialise in Greece (e.g. the Science Agora knowledge transfer hub, or the partnership of SEV with NTUA and “Demokritos”), it would be wise to foster and allow such a system to flourish, rather than imposing a top-down approach. In this regard, policy could encourage the creation of industrial research fora between academia and industry.

Policy 11: Activating university administrative capacity. This is key to the diffusion of academic research into industry, most notably including technology transfer offices (TTOs), which have been inaugurated lately. At the same time, it is essential to enhance Innovation and Entrepreneurship initiatives and units, which can expose scientists to ways in which their research can be commercialised and teach entrepreneurship to students, as well as promote the newly established Competence Centers, which aspire to organise and streamline university resources.

Policy 12: Building the capacity of public bodies to conduct procurement, aimed at developing innovation (Public Procurement for Innovation), and enhancing their digital capabilities and the provision of electronic services.

[1] Results are robust to different definitions and controls. See Anyfantaki et al. (2022) for further details and robustness checks.

[2] See Hsieh et al. (2019) for recent work on the importance of the allocation of human capital.

[3] Data for productivity come from Orbis, and include 17 countries. All measures are averaged for each sector across 2009-13 to improve reliability.

[4] More precisely, if the productivity cut-off to operate overseas is more or less similar across countries, and the distribution of productivities is shifted to the left for Greece relative to other advanced economies, then the productivity gap of those with overseas activities versus those without is expected to be larger in Greece.

[5] Gartzou-Katsouyanni (2021) conducts a number of case studies of local communities in the tourism and agri-food sectors in Greece, and identifies characteristics that can catalyse cooperation despite low levels of trust. Trust can also affect the attitudes of prospective employees, with important implications for the challenge of attracting expatriated Greek workers (Tasoulis et al., 2019)

References

Acemoglu, D., Aghion, P., Lelarge, C., Van Reenen, J. and Zilibotti, F., 2007. Technology, Information, and the Decentralization of the Firm. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(4), pp.1759-1799.

Adalet McGowan, M.A. and Andrews, D., 2015. Skill mismatch and public policy in OECD countries. OECD Economics Department Working Papers 1209.

Aghion, P. and Tirole, J., 1997. Formal and real authority in organizations. Journal of political economy, 105(1), pp.1-29.

Aghion, P., Bloom, N., Lucking, B., Sadun, R. and Van Reenen, J., 2021. Turbulence, firm decentralization, and growth in bad times. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 13(1), pp.133-69.

Andrews, D., Nicoletti, G. and Timiliotis, C., 2018. Digital technology diffusion: A matter of capabilities, incentives or both?, OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1476. OECD Publishing, Paris, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/7c542c16-en.

Arvanitis, S., Ley, M., Seliger, F., Stucki, T. and Wörter, M., 2013. Innovationsaktivitäten in der Schweizer Wirtschaft: Eine Analyse der Ergebnisse der Innovationserhebung 2011 (No. 39). KOF Studien

Baldwin, R., 2016. The Great Convergence: Information Technology and the New Globalization. Harvard University Press.

Bartelsman, E., Haltiwanger, J. and Scarpetta, S., 2013. Cross-country differences in productivity: The role of allocation and selection. American Economic Review, 103(1), pp.305-34.

Beck, M., Lopes-Bento, C., Schenker-Wicki, A., 2016. Radical or incremental: Where does R&D policy hit?. Research Policy, 45(4), pp. 869-883.

Beckmann, M., 2016. Working-time autonomy as a management practice. IZA World of Labor.

Bloom, N., Brynjolfsson, E., Foster, L., Jarmin, R., Patnaik, M., Saporta-Eksten, I. and Van Reenen, J., 2019. What drives differences in management practices?. American Economic Review, 109(5), pp.1648-83.

Bloom, N., Genakos, C., Martin, R. and Sadun, R., 2010. Modern management: good for the environment or just hot air?. The economic journal, 120(544), pp.551-572.

Bloom, N., Genakos, C., Sadun, R. and Van Reenen, J., 2012. Management practices across firms and countries. Academy of management perspectives, 26(1), pp.12-33.

Bloom, N., Eifert, B., Mahajan, A., McKenzie, D. and Roberts, J., 2013. Does management matter? Evidence from India. The Quarterly journal of economics, 128(1), pp.1-51.

Bloom, N. and Van Reenen, J., 2007. Measuring and explaining management practices across firms and countries. The quarterly journal of Economics, 122(4), pp.1351-1408.

Bloom, N. and Van Reenen, J., 2010. Why do management practices differ across firms and countries?. Journal of economic perspectives, 24(1), pp.203-24.

Bloom, N., Sadun, R. and Van Reenen, J., 2012. The organization of firms across countries. The quarterly journal of economics, 127(4), pp.1663-1705.

Bloom, N., Sadun, R. and Van Reenen, J., 2016. Management as a Technology? (No. w22327). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bloom, N., Kretschmer, T. and Van Reenen, J., 2009. Work-life balance, management practices and productivity. International differences in the business practices and productivity of firms, pp.15-54.

Bresnahan, T.F., Brynjolfsson, E. and Hitt, L.M., 2002. Information technology, workplace organization, and the demand for skilled labor: Firm-level evidence. The quarterly journal of economics, 117(1), pp.339-376.

Caloghirou, Y., Giotopoulos, I., Kontolaimou, A. and Tsakanikas, A., 2020. Inside the black box of high-growth firms in a crisis-hit economy: Corporate strategy, employee human capital and R&D capabilities. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, pp.1-27.

Cedefop, 2020. Skills forecast 2020: Greece. Cedefop skills forecast.

Cohen, W.M. and Levin, R.C., 1989. Empirical studies of innovation and market structure. Handbook of industrial organization, 2, pp.1059-1107.

Decker, R.A., Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R.S. and Miranda, J., 2017. Declining dynamism, allocative efficiency, and the productivity slowdown. American Economic Review, 107(5), pp.322-26.

Decker, R.A., Haltiwanger, J., Jarmin, R.S. and Miranda, J., 2020. Changing business dynamism and productivity: Shocks versus responsiveness. American Economic Review, 110(12), pp.3952-90.

De Massis, A., Frattini, F. and Lichtenthaler, U., 2013. Research on technological innovation in family firms: Present debates and future directions. Family Business Review, 26(1), pp.10–31.

Deming, D.J., 2017. The growing importance of social skills in the labor market. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 132(4), pp.1593-1640.

DIANEOSIS/ Laboratory of Industrial and Energy Economics (LIEE) at NTUA, 2021. Η Ελλάδα που Μαθαίνει, Ερευνά, Καινοτομεί και Επιχειρεί. Μια Ενοποιημένη Συστημική Στρατηγική με Επίκεντρο την Καινοτομία και τη Γνώση και ένα Πλαίσιο για την Υλοποίησή της Γιατί είναι αναγκαία, τι περιλαμβάνει, πώς υλοποιείται, με ποιους θα προωθηθεί;

Fons-Rosen, C., Kalemli-Ozcan, S., Sorensen, B., Villegas-Sanchez, C. and Volosovych, V., 2017. Foreign Investment and Domestic Productivity: Identifying Knowledge Spillovers and Competition Effects. NBER Working Paper 23643.

Gartzou-Katsouyanni, K., 2021. Cooperation against the odds: A Study on the Political Economy of Local Development in a Country with Small Firms and Small Farms. London School of Economics Dissertation.

Genakos, C., 2018. The tale of the two Greeces: Some management practice lessons. Managerial and Decision Economics, vol. 39(8), pp. 888-896.

Gereffi, G., Humphrey, J. and Sturgeon, T., 2005. The governance of global value chains. Review of international political economy, 12(1), pp.78-104.

Gorodnichenko, Y, Revoltella, D., Svejnar, J. and Weiss, C., 2018. “Resource Misallocation in European Firms: The Role of Constraints, Firm Characteristics and Managerial Decisions,” NBER Working Paper 24444.

Hsieh, C.T. and Klenow, P.J., 2009. Misallocation and manufacturing TFP in China and India. The Quarterly journal of economics, 124(4), pp.1403-1448.

Hsieh, C.T., Hurst, E., Jones, C.I. and Klenow, P.J., 2019. The allocation of talent and us economic growth. Econometrica, 87(5), pp.1439-1474.

Katsikas, D., 2021. Skills mismatch in the Greek labour market: Insights from a youth survey. ELIAMEP Policy Paper 71.

McGuinness, S. and Wooden, M., 2009. Overskilling, job insecurity, and career mobility. Industrial relations: a journal of economy and society, 48(2), pp. 265-286.

OECD (2013), “How Skills Are Used in the Workplace”, in OECD Skills Outlook 2013: First Results from the Survey of Adult Skills, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2019), “Greece”, in OECD SME and Entrepreneurship Outlook 2019, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2020a), Education policy Outlook: Greece.

Pellegrino, B. and Zingales, L., 2017. Diagnosing the Italian disease. NBER Working Paper No 23964.

Schivardi, F. and Schmitz, T., 2020. The IT revolution and southern Europe’s two lost decades. Journal of the European Economic Association, 18(5), pp .2441-2486.

Scur, D., Sadun, R., Van Reenen, J., Lemos, R. and Bloom, N., 2021. The World Management Survey at 18: lessons and the way forward. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 37(2), pp.231-258.

Taglioni, D. and Winkler, D., 2016. Making global value chains work for development. World Bank Publications.

Tasoulis, K., Krepapa, A. and Stewart, M.M., 2019. Leadership integrity and the role of human resource management in Greece: gatekeeper or bystander?. Thunderbird International Business Review, 61(3), pp.491-503.