This Policy Paper by Efthymios Papastavridis, Research Associate of ELIAMEP; Researcher and Part-time Lecturer, University of Oxford Fellow; Academy of Athens & Athens PIL Center, examines the maritime disputes between Greece and Turkey, in particular those concerning maritime delimitation and the breadth of the territorial sea of Greece, against the background of international law. It starts with setting out the historical and legal background of the continental shelf dispute in the Aegean Sea, in particular Greece’s applications before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the UN Security Council in 1976. Then, the paper considers the different legal positions of Greece and Turkey concerning the issues of the breadth of the territorial sea and the maritime delimitation and assesses these positions under international law. This assessment is followed by the discussion of the various means available under international law for the settlement of the maritime delimitation dispute under international law, in particular, its submission to the ICJ, which has often been at the front line of public and scholarly discourse. The paper concludes that international law provides a sufficient, clear and predictable legal framework for the resolution of the Greek-Turkish maritime dispute, which will be of the outmost benefit for both States and for the Eastern Mediterranean region as a whole.

You may access the paper here.

Introduction

Greece is admittedly a traditional maritime nation -the Greek-owned fleet represents nearly 21% of the global merchant fleet capacity-,[1] but also a coastal State that has a remarkably extensive coastline, thanks mainly to its hundreds of islands in the Aegean and Ionian Seas.[2] Also, Greece is situated at a strategic geographical position, linking the maritime commerce between the East and the West. Yet, notwithstanding these attributes, Greece appears quite reserved in exercising its rights under international law of the sea; strikingly, Greece has declared no maritime zones,[3] and has only one continental shelf delimitation agreement in force (with Italy in 1977),[4] while on 9 June 2020, Greece signed a second multi-purpose boundary agreement with Italy.[5]

“Greece appears quite reserved in exercising its rights under international law of the sea; strikingly, Greece has declared no maritime zones, and has only one continental shelf delimitation agreement in force (with Italy in 1977)”

In relation to the Aegean Sea, the reason behind this is, arguably, the pending Greek-Turkish maritime dispute(s). Greece has never concluded a maritime delimitation agreement with Turkey resolving the dispute over the continental shelf of the Aegean Sea pending since the 1970s, which, according to Greece, is the only unresolved dispute between the two countries.[6] On the other hand, Turkey has been regularly adding to the list of ‘unresolved disputes’ numerous others issues, including questions of sovereignty over certain islands, the demilitarized status of other islands, the right of Greece to extend its territorial sea up to 12 nautical miles (n.m.) and the delimitation of the territorial sea, the10 n.m. national airspace of Greece, the control of air traffic in the Aegean.[7]

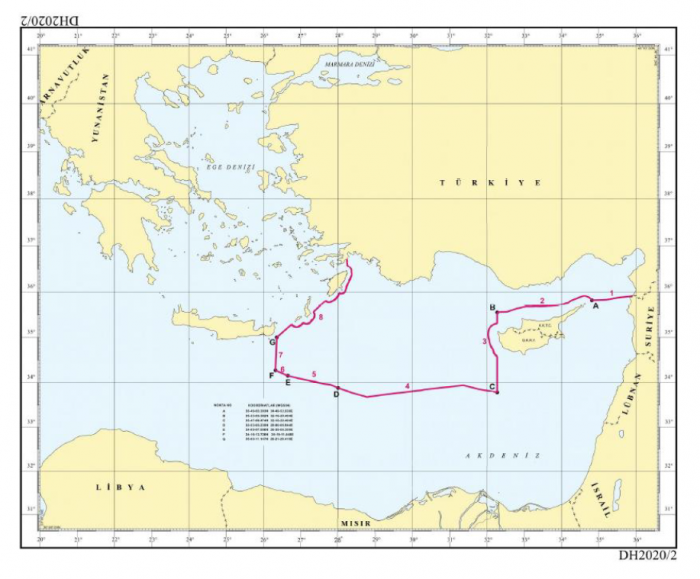

Relatedly, on numerous occasions Turkey has submitted to the United Nations Note Verbales with her continental shelf claims in the maritime areas of the Eastern Mediterranean, most recently on 18 March 2020.[8] This Note Verbale, which included an updated chart illustrating the Turkish claims (see Annex I), followed the conclusion of the controversial Memorandum of Understanding Between the Government of the Republic of Turkey and the Government of National Accord-State of Libya on Delimitation of Maritime Jurisdiction Areas in the Mediterranean, which was signed on 27 November 2019, and entered into force on 8 December 2019 (Turkey-Libya MoU).[9] Greece has vehemently protested against this MoU: amongst others, ‘the Greek Government express[ed] its strong opposition to the unlawful delimitation aimed at by the above agreement, which illegally overlaps on zones of legitimate and exclusive Greek sovereign rights, and rejects it in its entirety as null and void and without any effect on its sovereign rights’.[10]

“As the COVID-19 pandemic is (for the time being) facing out, one can reasonably predict that the maritime disputes between Greece and Turkey, further exacerbated by the ongoing migration/refugee crisis, will forcefully come to the fore.”

Undoubtedly, the maritime disputes between Greece and Turkey in the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean raise significant concerns and may seriously threaten the peace and security in the region, particularly in the event of unilateral hydrocarbon exploration drillings in disputed maritime areas, like those already occurring by Turkey off Cyprus. As the COVID-19 pandemic is (for the time being) facing out, one can reasonably predict that the maritime disputes between Greece and Turkey, further exacerbated by the ongoing migration/refugee crisis, will forcefully come to the fore. Indeed, as reported recently (1 June 2020), Turkey purports to grant exploration licenses to the Turkish State Petroleum Company (TPAO) in areas very close to Greek islands on the basis, amongst others, of the Turkey-Libya MoU.[11]

Against this backdrop, this paper aims to unpack the maritime disputes between Greece and Turkey, with particular emphasis placed upon those concerning maritime delimitation and the breadth of the territorial sea, and to explore the potential of resolving the maritime delimitation dispute under international law.

“…the paper argues that the international law provides a sufficient, clear and predictable legal framework for the resolution of the Greek-Turkish maritime dispute, which will be of the outmost benefit for both States and for the Eastern Mediterranean region as a whole.”

Accordingly, the remainder of this paper is structured as follows: In Section II, the paper sets out the historical and legal background of the continental shelf dispute in the Aegean Sea, in particular Greece’s applications before the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the UN Security Council in 1976. In Section III, the paper considers the different legal positions of Greece and Turkey concerning the issues of the breadth of the territorial sea and the maritime delimitation and examines those positions against the background of the international law of the sea. In Section IV, the paper discusses the various means for the settlement of the present dispute under international law, in particular, its submission to the ICJ, which has often been at the front line of public and scholarly discourse. By way of conclusion, in Section V, the paper argues that the international law provides a sufficient, clear and predictable legal framework for the resolution of the Greek-Turkish maritime dispute, which will be of the outmost benefit for both States and for the Eastern Mediterranean region as a whole.

The Historical and Legal Background of the Continental Shelf Dispute: The Recourse to the UN Security Council and the ICJ

On 10 August, 1976, Greece addressed a communication to the President of the Security Council requesting an urgent meeting of the Council on the ground that ‘following recent repeated flagrant violations by Turkey of the sovereign rights of Greece in the continental shelf in the Aegean, a dangerous situation has been created threatening international peace and security’.[12] On the same day, Greece filed with the Registrar of the International Court of Justice an Application instituting proceedings against Turkey in respect of a dispute concerning the delimitation of the continental shelf appertaining to Greece and Turkey in the Aegean Sea and the rights of the parties thereover.[13] Also, on the same day Greece filed a request for interim measures of protection asking the Court to direct that both Greece and Turkey (1) unless with consent of each other and pending the final judgment of the Court in this case, refrain from all exploration activity or any scientific research, with respect to the continental shelf areas within which Turkey has granted such licenses or permits or adjacent to the Islands, or otherwise in dispute in the present case, (2) refrain from taking further military measures or actions which may endanger their peaceful relations.’[14]

“This strategy of Greece, namely the simultaneous appeal to the most political of the political organs of the United Nations, the Security Council, and its principal judicial organ, the Court, did not prove particularly fruitful.”

This strategy of Greece, namely the simultaneous appeal to the most political of the political organs of the United Nations, the Security Council, and its principal judicial organ, the Court, did not prove particularly fruitful. Greece was only partly successful in obtaining some relief from the Security Council in paragraphs 1 and 2 of Resolution 395(1976),[15] although it failed to receive from the Court satisfaction for its request for interim measures.[16] Turkey was successful before the Court in so far as the denial of the Greek request was concerned though it failed to persuade the Court that the Greek Application was ‘premature’. Turkey was also partly successful in the Security Council inasmuch as paragraph 3 of Resolution 395(1976) called for resumption of direct negotiations and paragraph 4 invited both governments ‘to take into account the contribution that appropriate judicial means, in particular the International Court of Justice, are qualified to make to the settlement of any remaining legal differences which they may identify in connection with their present dispute.’[17] Finally, Turkey was successful in the rejection of Greek application, as on 19 December 1978 the Court delivered its judgment finding that it is without jurisdiction to entertain the Application.[18] This was the position of Turkey from the initiation of the proceedings before the Court and was underscored by her absence in the proceedings.[19]

“The origin of the dispute lays in the decision of the Turkish Government, towards the end of 1973, to grant to the Turkish State Petroleum Company (TPAO) the right to carry out exploration for petroleum in 27 regions of the Aegean continental shelf.”

The origin of the dispute lays in the decision of the Turkish Government, towards the end of 1973, to grant to the Turkish State Petroleum Company (TPAO) the right to carry out exploration for petroleum in 27 regions of the Aegean continental shelf east of a line starting at the mouth of the Evros River in the north and extending southwards and to the West of the Greek islands of Chios and Psara, which Greece considered to encroach upon the continental shelf of its islands.[20] In replying to Greece, Turkey submitted, amongst others, that while since the 1960’s Greece had granted numerous exploration licenses and drilled for oil in the Aegean ‘outside Greek territorial waters’, Turkey had ‘started its research activities on the natural prolongation of Anatolian peninsula in 1974, 11 years later than Greece’.[21]

The dispute that started at the end of 1973 had numerous other episodes,[22] including various bilateral meetings between representatives of the two States, ranging from meetings at the highest level between the two Prime Ministers (e.g. in Brussels on 31 May 1975)[23] to a technical meeting of the delegations and experts of the two Governments in Berne on 19 and 20 June 1976 (Berne Meeting),[24] and other incidents at sea, such as the sending of Turkish seismographic vessels in the Aegean. It was exactly the activities of the Turkish research vessel MTA Sismik–I on 6 August 1976, which was observed engaging in seismic exploration of an area of the continental shelf of the Aegean,[25] that prompted the reaction of Greece before the UN Security Council and the ICJ.

As to the process before the Security Council, Greece, invoking Article 35 (1) of the UN Charter,[26] appealed to the Council ‘in order to avert the danger of disturbing the peace, which is being seriously threatened’ by the above-mentioned ‘seismological explorations’ conducted by Turkey with the vessel Sismik-I. In the Council, Greece maintained its stand and asked the Council to let Turkey know ‘that it must suspend its provocative acts. The United Nations was not in time to stop the tragedy of Cyprus. It can now prevent a new tragedy in the Aegean’.[27] Turkey responded by restating its position with respect to the substantive dispute, namely that in the absence of an agreed delimitation of the continental shelf ‘the Greek claim of violation of the Greek sovereign rights is completely unfounded’.[28] In addition, Turkey related the incident with the alleged ‘militarization’ by Greece of its islands in violation of its international obligations.[29]

“… the Security Council did not attempt to assess blame on one side or the other for the situation in the Aegean nor did it attempt to deal directly with the substance of the dispute.”

As expected, the Security Council did not attempt to assess blame on one side or the other for the situation in the Aegean nor did it attempt to deal directly with the substance of the dispute, although it made a recommendation with respect to the procedure which it considered appropriate, i.e. the recourse to the ICJ.[30] Indeed, Resolution 395(1976), as is so often the case with Security Council Resolutions, did not indicate on which article of the Charter it was based. Members of the Council expressed different views in this respect.[31] Evidently, as indicated earlier, Resolution 395(1976) has two parts: in the first part, paragraphs 1 and 2, the Council calls, as the United Kingdom representative put it, ‘for restraint on both sides and must then go on to urge them to do everything in their power to reduce the present tensions’.[32] In paragraphs 3 and 4, the Resolution addresses itself to the legal aspects of the dispute, calling for its resolution by legal means. This appears to raise a question of principle, namely the propriety of the Council making a recommendation with regard to the method of settling a dispute when the same dispute was sub judice in the ICJ. In fact, this was accepted with comfort by Turkey, since it could be construed as an indication that the application then pending before the ICJ was ‘premature’. In any event, the Council succeeded in having the tension diffused. However, as Leo Gross observes, ‘Greece, in appealing to the Court, has taken a step in the direction of depoliticizing the dispute; the Security Council has taken a step in repoliticizing it’.[33]

As to the recourse to the ICJ, the following remarks are in order: first, with respect to the request for the indication of provisional measures, this had two objectives: to enjoin both Greece and Turkey (a) from conducting further exploration or research in the contested areas and (b) from taking measures likely to endanger their peaceful relations. The request was based on Article 33 of the General Act of 1928 for the Pacific Settlement of International Disputes (‘1928 Act’).[34] The Court found it unnecessary ‘to reach a final conclusion at this stage of the proceedings’ on the question of jurisdiction and proceeded to examine the request of Greece. In particular, the Court examined whether the concessions granted and the seismic explorations undertaken by Turkey were in the nature of causing or threatening an irreparable prejudice to the rights claimed by Greece as its own. The Court stated that a prejudice is not irreparable if it is ‘capable of reparation by appropriate means’, and found that in the present case there was no threat of irreparable injury, and therefore no need or justification for granting provisional measures.[35]

“…key fact militating against the order of interim measures was that the seismic exploration undertaken by Sismik-I involved no risk of physical damage to the seabed or subsoil or to their natural resources.”

In terms of substance of this Order, it appears that the key fact militating against the order of interim measures was that the seismic exploration undertaken by Sismik-I involved no risk of physical damage to the seabed or subsoil or to their natural resources, and that ‘no suggestion had been made that Turkey has embarked upon any operations involving the actual appropriation or other use of the natural resources of the areas of the continental shelf which are in dispute’.[36] It is telling that almost 40 years later, in 2015, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) held in the Ghana/Côte d’Ivoire case that exploratory drillings, which might cause permanent damage on the seabed and subsoil of the continental shelf, could bring about irreparable harm or prejudice. Accordingly, the Tribunal upheld the request for provisional measures and ordered Ghana not to commence any new drillings.[37]

“… the decision not to prescribe interim measures in a case, over which the jurisdiction of the Court was rather controversial, and in which the Security Council had not considered to constitute a matter of urgency, was, arguably, a prudent choice.”

In terms of judicial policy, the decision not to prescribe interim measures in a case, over which the jurisdiction of the Court was rather controversial, and in which the Security Council had not considered to constitute a matter of urgency, was, arguably, a prudent choice. Indeed, as one commentator observes, ‘taken together with certain statements made by Members of the Court in their individual opinions, invites the suspicion, confirmed by the Judgment of 1978, that the Court already had doubts whether it would eventually find that it had jurisdiction on the merits and did not wish to get itself once again into a situation in which it would have indicated interim measures of protection without being able eventually to affirm its jurisdiction to deal with the merits’.[38]

“…the Court had the task to establish whether both parties had given their consent to its jurisdiction, which is a prerequisite for a case to be heard by the ICJ.”

Second, with respect to the Court’s Judgment on its jurisdiction (1978), noteworthy is, first, that the Court refused Greece’s request for a postponement just before the case heard on 4 October 1978 and was equally firm in rejecting the Turkish contention that the Court should decline to exercise jurisdiction because negotiations were in progress. The Court said that ‘the fact that negotiations are being actively pursued during the present proceedings is not, legally, any obstacle to the exercise by the Court of its judicial function’.[39] On the main issue of its jurisdiction, the Court had, in essence, the task to establish whether both parties had given their consent to its jurisdiction, which is a prerequisite for a case to be heard by the ICJ (Article 36 of the ICJ Statute).[40] In the case at hand, Greece contended that its jurisdiction was found on Article 17 of the 1928 Act and alternatively, on the Joint Brussels Communiqué of 31 May 1975 between the two Prime Ministers, while Turkey, which, as indicated above, did not take part in the proceedings, contended that the Act was no longer in force and if it was, the dispute was excluded by the Greek reservation.

The Court avoided to take a firm position on whether the Act of 1928 was still in force, stating that ‘any pronouncement of the Court as to the status of the 1928 Act, whether it were found to be a convention in force or to be no longer in force, may have implications in the relations between States other than Greece and Turkey’.[41] Accordingly, the Court next turned its attention to the Greek reservation appended to Greece’s instrument of accession to the Act, dated 14 September 1931, which read as follows: ‘[t]he following disputes are excluded from the procedures described in the General Act…(b) disputes concerning questions which by international law are solely within the domestic jurisdiction of States, and in particular disputes relating to the territorial status of Greece, including disputes relating to its rights of sovereignty over its ports and lines of communication’ (emphasis added).

Under international law, either of the parties to the case may, in line with the principle of reciprocity, ‘enforce’, i.e. invoke the reservation of the other party, such as here, Greece, to any treaty that grants jurisdiction over a dispute to the Court pursuant to Article 36 (1) of the ICJ Statute. In the view of the Court, Turkey did so in its observations to the Court on 25 August 1976.[42] As to the reservation itself, Greece maintained that reservation (b) could not be considered as covering the dispute regarding the continental shelf of the Aegean Sea and therefore did not exclude the normal operation of Article 17 of the Act.[43]

“…the Court observed that it would be difficult to accept the proposition that delimitation is entirely extraneous to the notion of territorial status, and pointed out that a dispute regarding delimitation of a continental shelf tends by its very nature to be one relating to territorial status.”

Nevertheless, the Court was of the view that the expression ‘disputes relating to the territorial status of Greece’ must be interpreted in accordance with the rules of international law as they exist today and not as they existed in 1931.[44] In examining whether the reservation in question should or should not be understood as comprising disputes relating to the geographical extent of Greece s rights over the continental shelf in the Aegean Sea, the Court observed that it would be difficult to accept the proposition that delimitation is entirely extraneous to the notion of territorial status, and pointed out that a dispute regarding delimitation of a continental shelf tends by its very nature to be one relating to territorial status, inasmuch as a coastal State’s rights over the continental shelf derive from its sovereignty over the adjoining land. Hence, Turkey’s invocation of the reservation had the effect of excluding the dispute from the application of Article 17 of the 1928 Act, which therefore could not have been a valid basis for the Court’s jurisdiction.[45]

As to the alternative basis that Greece put forth, i.e. the Brussels Joint Communiqué of 31 May 1975, it was a Communiqué issued directly to the press by the Prime Ministers of Greece and Turkey following a meeting between them on that date, which according to Greece directly conferred jurisdiction on the Court. The relevant paragraphs of the Brussels Communiqué read as follows:’… the two Prime Ministers decided [ont décidé] that those problems should be resolved [doivent être résolus] peacefully by means of negotiations and as regards the continental shelf of the Aegean Sea by the International Court at The Hague. They defined the general lines on the basis of which the forthcoming meetings of the representatives of the two Governments would take place’.[46] The Court did not preclude the possibility that this instrument might constitute an agreement under international law, yet it found nothing to justify the conclusion that it did constitute ‘an immediate commitment by the Greek and Turkish Prime Ministers, on behalf of their respective Governments, to accept unconditionally the unilateral submission of the present dispute to the Court’.[47]

“…this case demonstrates how hazardous it is to institute proceedings in the ICJ by way of unilateral Application. This should be remembered in view of the still pending-after 45 years- Aegean Sea continental shelf dispute.”

In conclusion, even if the Court’s position that a dispute about the boundary of continental shelf related to the territorial status of Greece was not particularly convincing,[48] it is true that this case demonstrates how hazardous it is to institute proceedings in the ICJ by way of unilateral Application. This should be remembered in view of the still pending-after 45 years- Aegean Sea continental shelf dispute.

To date, there has been no other significant milestone concerning the settlement of the continental shelf dispute, albeit various negotiating efforts, such as the exploratory talks between delegations of the two States (2002-2016).[49]

The Maritime Disputes between Greece-Turkey under International Law of the Sea

Greece and Turkey have markedly different positions both as to the existing disputes between them and as to the legal framework governing their substance. As indicated in the Introduction, Greece’s consistent view is that there is only one outstanding legal dispute between the two States, namely that concerning the delimitation of the continental shelf (and potentially the -future- Exclusive Economic Zone [EEZ] between the two States).[50] On the other hand, Turkey has been systematically widening the spectrum of the perceived ‘disputes’ between the two States (e.g. demilitarization, grey zones, airspace).[51] This paper focuses only on the maritime disputes between the two countries, i.e. those concerning maritime boundaries and the breadth of the Greek territorial sea.

“…Greece’s consistent view is that there is only one outstanding legal dispute between the two States, namely that concerning the delimitation of the continental shelf (and potentially the -future- Exclusive Economic Zone [EEZ] between the two States). On the other hand, Turkey has been systematically widening the spectrum of the perceived ‘disputes’ between the two States (e.g. demilitarization, grey zones, airspace).”

The concept of the term ‘dispute’, which this paper adopts for its purposes, is based on the legal definition of ‘dispute’ under international law. According to widely accepted jurisprudence, a dispute is ‘a disagreement on a point of law or fact, a conflict of legal views or of interests between parties’.[52] In order for a dispute to exist, ‘[i]t must be shown that the claim of one party is positively opposed by the other and that the two sides must ‘hold clearly opposite views’ concerning the question of the performance or non-performance of certain international obligations’.[53] Further, international courts and tribunals note that the ‘determination of the existence of a dispute is a matter of substance, and not a question of form or procedure’, and that whether a dispute exists is a matter for ‘objective determination’.[54]

In light of the foregoing, it readily appears that in view of the opposing legal views of the two States concerning matters of delimitation and the breadth of the territorial sea of Greece, these ‘disagreements on points of law’ constitute ‘disputes under international law’, and in particular, the law of the sea. Accordingly, in the remainder of the present section we will put forth these ‘legal views’ of Greece and Turkey concerning the issues of the breadth of the territorial sea and the maritime delimitation and examine them against the background of the international law of the sea.

- The Breadth of the Territorial Sea

a) The Greek Position

Greece enjoys sovereignty in its territorial sea, which is considered part of its territory, within the limits that it has set out by national legislation. Indeed, the breadth of Greece’s territorial sea was set at 6 nautical miles from its coastline (‘normal baselines’)[55] in 1936 (Law No 230/1936 as amended by Presidential Decree 187/1973). The limits of the superjacent airspace of the territorial sea of Greece remains at 10 nautical miles, pursuant to the Decree of 6 September 1931 in conjunction with the Law 5017/1931.[56]

“Greece’s assertion is that under customary law, which is the applicable law between the two States, Greece has an unfettered right to extend the breadth of its territorial sea up to 12 n.m, a right which Turkey cannot dispute. Such right is neither restricted, nor subject to any exception by international law.”

As the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) states: ‘according to customary international law, which is also codified in the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Greece has the right to extend its territorial waters to 12 nautical miles’.[57] The reference to customary international law at the start is intentional, since the applicable law between Greece and Turkey is customary international law and not UNCLOS,[58] to which Turkey is not a party.[59]

Further, Greece notes that ‘[t]his right to extend territorial waters up to is a sovereign right which can be unilaterally exercised and is therefore not subject to any kind of restriction or exception and cannot be disputed by third counties. Article 3 of UNCLOS which codifies a rule of customary law, does not provide for any restrictions and exceptions with regard to that right. The overwhelming majority of coastal States, except for a few exceptions, have determined the breadth of their territorial sea at 12 nautical miles. Turkey itself has extended its territorial waters to 12 nautical miles in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean already since 1964’.[60]

In short, Greece’s assertion is that under customary law, which is the applicable law between the two States, Greece has an unfettered right to extend the breadth of its territorial sea up to 12 n.m, a right which Turkey cannot dispute. Such right is neither restricted, nor subject to any exception by international law, as Turkey may contend. Further, Greece underscores that even Turkey itself has proclaimed a 12 nm territorial sea in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean. Thus, Greece is entitled to extend, whenever it considers this appropriate, its territorial sea up to 12 n.m. (circa 20 km) from its coast.

Indeed, upon ratifying the UNCLOS Greece made the following statement under Article 310 UNCLOS: ‘[I]n ratifying the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, Greece secures all the rights and assumes all the obligations deriving from the Convention. Greece shall determine when and how it shall exercise these rights, according to its national strategy. This shall not imply that Greece renounces these rights in any way.’[61] Such statement was not, in strict legal terms, necessary for the actual exercise of the right to extend the territorial sea, since the right under Article 3 of UNCLOS is not subject to any deadline or extinction. However, it bears significance in preempting any allegations that Greece has lost this right due to its inaction (along the lines of desuetude,[62] or extinctive prescription,[63] or renunciation of rights[64] in international law) or that it has acquiesced to, i.e. it has tacitly accepted,[65] the Turkish positions in the Aegean Sea. In any case, according to well-established case-law, ‘waivers or renunciations of claims or rights must either be express or unequivocally implied from the conduct of the State alleged to have waived or renounced its right’.[66] Greece’s conduct in no way warrants such implication. Thus, any claim for the renunciation of this right in the case of the Aegean Sea shall not be taken lightly.

b) The Turkish Position

On the other hand, Turkey has firmly negated the right of Greece to extend its territorial sea in the Aegean. As the Turkish MFA notes:

‘under the present 6 mile limit, Greek territorial sea comprises approximately 43.5 percent of the Aegean Sea. For Turkey, the same percentage is 7.5 percent. The remaining 49 percent is high seas. It is evident that the extension by Greece of her territorial waters beyond the present 6 miles in the Aegean would have most inequitable implications and would, therefore, constitute an abuse of right. If the breadth of Greek territorial waters is extended to 12 miles due to the existence of the islands, Greece would acquire approximately 71.5 percent of the Aegean Sea, while Turkey’s share would increase to only 8.8 percent….The impact of such a Greek extension of its territorial waters would be to deprive Turkey, one of the two coastal States of the Aegean, from her basic access to high seas from her territorial waters, the economic benefits from the Aegean, scientific research etc’.[67]

“”It holds true that Turkey has long objected to any extension of the territorial sea in the Aegean Sea more than 6 n.m.”

It holds true that Turkey has long objected to any extension of the territorial sea in the Aegean Sea more than 6 n.m.[68] For example, throughout the Third Conference on the Law of the Sea (1973-1982) (UNCLOS III), Turkey tried to insert a clause into the draft Article 3 (the breadth of the territorial sea) that ‘would require states bordering enclosed and semi-enclosed seas to determine the breadth of their territorial waters by mutual agreement’.[69] Also, as the Turkish representative noted in a speech at the Plenary of the Conference, ‘…in regions of semi-enclosed seas where the present breadth of territorial sea was less than 12 nautical miles, States should not exercise unilaterally the right given to them under Article 3 without taking into account the legitimate interests of neigbouring countries’.[70]

At the Final Session of UNCLOS III, the Head of the Turkish Delegation made a comprehensive statement on Turkey’s position, which with respect to the territorial sea enunciated that:

‘in the narrow seas, such as enclosed and semi-enclosed seas, on which Turkey is bordered, the extension of the territorial sea in disregard of special circumstances of these seas and in a manner which would deprive another littoral State of its existing rights and interests creates inequitable results which certainly call for the application of the doctrine of abuse of right. Turkey is of the opinion that the 12-nautical miles limit for territorial waters has not acquired the character of the rule of customary law in cases where the application of such a rule constitutes an abuse of right. Turkey in course of the preparatory stages of the Conference as well as during the Conference, has been a persistent objector to the 12 nautical miles limit…this limit cannot be claimed vis-à-vis Turkey.’[71]

“…Turkey in course of the preparatory stages of the Conference as well as during the Conference, has been a persistent objector to the 12 nautical miles limit…this limit cannot be claimed vis-à-vis Turkey.’”

Noteworthy is also that Turkey promulgated a new Territorial Sea Act (No. 2674) of 20 May 1982, which repealed the 1964 legislation (Law No 476), in which it enunciated that ‘the breadth of the territorial sea shall be of six nautical miles’.[72] However, it reserved that ‘the Council of Ministers has the right to establish the breadth of the territorial sea, in certain seas, up to a limit exceeding six nautical miles, under reservation to take into account all special circumstances and relevant situations therein, and in conformity with the equity principle’.[73] Indeed, by Decree No. 8/5742 of 1982, Turkey maintained the 12-nautical miles territorial sea limit which previously existed in the Black Sea and in the Mediterranean Sea.[74] In justifying the extension of the territorial sea in the Black Sea, Turkey claims that this had occurred on the basis of the principle of reciprocity in relation to its neighbors there, which had already proclaimed a 12 miles territorial sea.[75]

A final point on this is that Turkey has vehemently objected to date to any thoughts of Greece or indications that it is about to extend the breadth of the territorial sea in the Aegean Sea, with the highlight being the Resolution of the National Assembly of Turkey on 8 July 1995 (just prior to the ratification of UNCLOS by Greece) authorizing the Turkish government to use military means against Greece, should the latter decide to extend its territorial waters over 6 nautical miles (the famous casus-belli of Turkey).[76]fto

To summarize the relevant Turkish positions:

i) Turkey contends that it is not bound by the provision of Article 3 of UNCLOS either as treaty or as customary law, since, first, Article 3 does not reflect custom, and second, in any case, Turkey has persistently objected to this rule. Thus, the 12 nm rule cannot be claimed vis-à-vis Turkey.

ii) Any extension of the territorial sea of littoral to semi-enclosed seas States, such as Greece and Turkey in the Aegean Sea shall be based on a mutual agreement.

iii) Due to the special circumstances of the Aegean Sea, any unilateral extension of the territorial sea of Greece beyond the 6 n.m. would constitute an abuse of right under international law.

iv) Any such extension would restrict the access of Turkey to the high seas regime, including fisheries, marine scientific research etc.

c) The Relevant International Law

i) Law of the Sea

Article 2 (1) UNCLOS ascribes to the coastal State sovereignty over the territorial sea. The sovereignty of the coastal State extends also to the airspace above the territorial sea, in addition to its seabed and subsoil. The rights of the coastal State over the territorial sea do not differ in nature from rights exercised over land territory, but they are subjected to limitations, as noted in Article 2 (3) UNCLOS, that is, the regimes of innocent and transit passage and other rules of international law.

“…in order to be able to oppose their territorial seas to third States, it is of paramount significance that coastal States, adhere to the requirements of UNCLOS and customary law concerning the breadth of the territorial sea.”

As the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has stated in the 1951 Fisheries case, ‘although it is true that the act of delimitation is necessarily a unilateral act, because only the coastal State is competent to undertake it, the validity of the delimitation with regard to other States depends upon international law’.[77] Therefore, in order to be able to oppose their territorial seas to third States, it is of paramount significance that coastal States, such as here Greece, adhere to the requirements of UNCLOS and customary law concerning the breadth of the territorial sea.

Article 3 UNCLOS provides that ‘every State has the right to establish the breadth of its territorial sea up to a limit not exceeding 12 nautical miles, measured from baselines determined in accordance with this Convention’.[78] In contrast to the continental shelf, which exists ipso facto and ab initio, i.e. without any declaration on the side of the coastal State,[79] the coastal State must act to establish the breadth of the territorial sea. The State establishes the territorial sea in a unilateral act, which must be undertaken within the limits circumscribed by international law, that is the 12 n.m. limit in accordance with the UNCLOS.

“The right of the coastal States to extend their territorial sea up to 12 n.m. is considered also part of customary law, and as such applicable vis-à-vis Turkey.”

The right of the coastal States to extend their territorial sea up to 12 n.m. is considered also part of customary law,[80] and as such applicable vis-à-vis Turkey. As two leading authorities observe, ‘no State seems to be in a position to object to a 12 NM limit’.[81]

“States may decide to gradually extend their territorial seas or may use different limits in different parts of their coast.”

Accordingly, the State is free to choose any breadth of the territorial sea as long as it does not exceed 12 n.m., but, there is no obligation to use the full distance…’.[82] States may decide to gradually extend their territorial seas or may use different limits in different parts of their coast. As the authoritative Virginia Commentary to the UNCLOS observes, ‘[i]t is clear from the text that article 3 confers upon every coastal State the right to establish the breadth of its territorial sea up to the maximum limit of 12 nautical miles, measured from the baselines. The article does not preclude a State from establishing different breadths, within that maximum limit, for different parts of its coast’.[83] Thus, any gradual extension by Greece of its territorial sea to 12 n.m., for example starting from the the Ionian Sea and moving to Crete etc., is lawful and in no way may implies any renunciation of Greece’s right to do so subsequently in other parts of its territory.

“Thus, any gradual extension by Greece of its territorial sea to 12 n.m., is lawful and in no way may implies any renunciation of Greece’s right to do so subsequently in other parts of its territory.”

Noteworthy is also that neither in Article 3 nor in other parts of the Convention, such as, aptly, Part IX concerning enclosed or semi-enclosed seas,[84] does UNCLOS pose any other limitation or qualification for such extension, as Turkey advocated during the Third Conference on the Law of the Sea, e.g. a requirement for mutual agreement.[85] In particular, Article 123 UNCLOS calling for the cooperation of States bordering semi-enclosed seas is ‘interpreted as a provision that ‘stimulates the cooperation of States and international organisations in respect of the use and protection of enclosed or semi-enclosed seas as well as to the adoption of regional and sub-regional rules concerning particular seas’,[86] but in no way dictates such cooperation, as evinced by the use of the term ‘should’ by the relevant provision.[87] In any case, it is indisputable that the jurisdiction, rights, including the rights under Article 3, and duties of coastal States and other maritime States are not affected by Article 123 UNCLOS.[88] That said, the obligation of coastal States bordering semi-enclosed seas to cooperate for the conservation of marine living resources, i.e. fisheries, and the protection of the marine environment remain intact under other provisions of the UNCLOS and customary law.

Nor is there any time frame or deadline for the exercise of the right in question. E contrario, in the cases that the Convention intended to pose a time frame for the exercise of rights thereunder, it did so explicitly, e.g. in relation to the faculty of coastal States to submit information to the Commission on the Limits of Continental Shelf in order to claim a continental shelf beyond 200 n.m.[89] It is inferred from the lack of any similar requirement under Article 3 UNCLOS that coastal States are free to extend the breadth of their territorial sea whenever they decide to do so. In fact, the imposition of strict temporal requirements to claim a ‘full’ territorial sea would run contrary to State sovereignty, as construed in the famous Lotus case (Permanent Court of International Justice, 1927).[90]

“Such right to extend the territorial sea is subject to no exception or qualification, be it temporal or geographical Hence, in principle, Greece is entitled to extend its territorial sea up to 12 n.m., and this entitlement is opposable to Turkey under customary international law.”

In concluding, under the law of the sea, as reflected in Article 3 UNCLOS, coastal States may extend their territorial seas up to 12 n.m., provided that there are no overlapping areas of territorial sea between neighbouring States, whether opposite or adjacent to each other, which calls for delimitation pursuant to Article 15 UNCLOS. Such right to extend the territorial sea is subject to no exception or qualification, be it temporal (time frame for the extension) or geographical (territorial seas in semi-enclosed sea). Hence, in principle, Greece is entitled to extend its territorial sea up to 12 n.m. (where applicable), and this entitlement is opposable to Turkey under customary international law, that is, Turkey must respect this right of Greece.

ii) Persistent Objector

Turkey contends that even if Article 3 UNCLOS reflects customary law, its provision is not opposable to Turkey, since the latter has been a persistent objector to the rule in question. Indeed, it is widely held that a State that has persistently objected to an emerging rule of customary international law, and maintains its objection after the rule has crystallized, is not bound by it.[91] Decisions of international and domestic courts and tribunals have referred to the ‘persistent objector’ rule,[92] and, the International Law Commission (ILC) -the secondary UN organ responsible for the codification and progressive development of international law- has included the rule in its –non-binding- 2018 Draft Conclusions on the Identification of Customary International Law.[93] Interestingly, both the Commentary to the Draft Conclusion 15 on ‘persistent objector’ and the Third Report of the Special Rapporteur of the ILC on this topic, allude to Turkey’s stance vis-à-vis the 12 n.m. rule during the Third Conference on the Law of the Sea as an example of State practice in support of the ‘persistent objector’ doctrine.[94]

Without dwelling upon the legal status and merits of the ‘persistent objector’ rule in international law,[95] suffice it to note that Turkey, notwithstanding the above references, cannot claim to be a ‘persistent objector’ to the 12 n.m. rule for the very simple reason that it has accepted itself the rule in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean.[96] By extending its territorial sea to 12 n.m. in these regions in 1964 (and later confirmed in 1982), Turkey negated the strict requirement which the rule in question is subjected to, i.e. that, as stated by the ILC, ‘the objection must be clearly expressed, meaning that non-acceptance of the emerging rule or the intention not to be bound by it must be unambiguous’.[97] By benefiting from the rule itself, to which, allegedly it objects, a State loses its right to be considered as a ‘persistent objector’ in this regard.[98]

As a matter of fact, Turkey never intended to be a persistent objector to the rule that a coastal State may claim up to 12 n.m. territorial sea; rather its intention was to add further qualifications to the 12 n.m. rule with respect to semi-enclosed seas, like the need for reciprocity or mutual agreement. As the ICJ famously acknowledged in the Case Concerning Military and Paramilitary Activities in and against Nicaragua (1986), the significance of invoking an exception to a rule is ‘to confirm rather than to weaken the rule’.[99] In the present case, the endeavour to include an exception to the 12 n.m. rule confirms rather than weakens the emerging normative status of the rule concerned. The fact that Turkey never flatly rejected the 12 n.m. rule is also evident from its relevant statements at the Third Conference.[100] Such exception or qualification in respect of semi-enclosed seas was never accepted by the Conference, nor has it entered the corpus of the treaty and customary international law. Moreover as recently upheld in the South China Sea Arbitration, the unilateral modification of the UNCLOS and the relevant customary law requires, most importantly, the acquiescence of all parties involved,[101] which Greece, obviously, has never displayed.

iii) Abuse of right

Turkey maintains that any extension of the territorial waters of Greece beyond 6 n.m. would amount to an abuse of right.[102] The doctrine of ‘abuse of rights’, enshrined in Article 300 UNCLOS, is considered a general principle of law, which controls the exercise of rights by States.[103] It prohibits a State exercising a right either in a way which impedes the enjoyment by other States of their own rights or for an end different from that for which the right was created, to the injury of another State. However, its customary nature is not unequivocally accepted. Indeed, as Kiss asserts, ‘it may be considered that international law prohibits the abuse of rights. However, such prohibition does not seem to be unanimously accepted in general international law’.[104] Indeed, on several occasions before the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) abuse of rights was pleaded and rejected at the merits phase for want of sufficient proof.[105] Similarly, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) has abstained from taking a firm position on its status, and in no case has explicitly accepted the argument.[106]

Whatever its customary status, the plea of ‘abuse of rights’ has a very high threshold under international law, which, arguably, is unlikely to be reached in the case of a unilateral extension of the territorial sea of Greece. Even if Greece extends its territorial sea to the fullest possible extent, i.e. 12 n.m., in the Aegean Sea, Turkey may still enjoy its rights under international law, including its own right to extend its territorial sea (for the overlapping areas there should be delimitation process), or the rights that it enjoys as a flag State, such as the freedoms of fishing, marine scientific research and of course navigation in the remaining areas of the high seas (and the rights of innocent and transit passage in Greece’s territorial seas). Actually, in no way the extension of the territorial sea of Greece would seem to be ‘an arbitrary exercise of a right by one State resulting in an injury to a second State’.[107] In such an assessment of arbitrariness, the overall conduct of Greece, which never ceased to be willing to resolve the bilateral issues in good faith, would be a key factor.

iv) Navigation and other Turkish interests

Finally, the Turkish position, inexorably linked with the above argument of abuse of rights, is that a future Greek extension of its territorial waters would deprive Turkey, ‘from her basic access to high seas from her territorial waters, the economic benefits from the Aegean, scientific research etc’.[108] As claimed above, international law safeguards such rights, including in the territorial sea of a third State. In particular, Turkey will never cease to enjoy the freedoms of the high seas, enshrined in Article 87 UNCLOS, which reflects customary law, in the remaining parts of the high seas. Such freedoms are predominantly the freedoms of navigation, overflight, fishing, marine scientific research etc.[109] More pertinently, the access of Turkey to the high seas of the Eastern and mainly the Central Mediterranean through the Greek territorial waters will be safeguarded by the rights of innocent and transit passage that UNCLOS and customary law provide for. And whereas the customary legal framework of the right of transit passage, i.e. the freedoms of navigation and overflight through straits used for international navigation,[110] is not crystal-clear yet,[111] the right of Turkish ships[112] to innocent passage, i.e. to navigate through the territorial sea of Greece without requesting permission to do so, under certain requirements posed by Article 18 (meaning of term ‘passage’)[113] and Article 19 (meaning of term ‘innocent’) UNCLOS,[114] is undisputed under customary international law. It follows that the claim that the extension of the territorial sea will deprive Turkey from its fundamental rights, such as access to the high seas, is untenable.

“…the claim that the extension of the territorial sea will deprive Turkey from its fundamental rights, such as access to the high seas, is untenable.”

v) Concluding Remarks

The right of Greece to unilaterally extend its territorial sea up to 12 n.m. is well-founded in international law of the sea, while a closer look at Turkish claims to the contrary reveals their tenuous legal ground. Greece may extend its territorial sea whenever and wherever it considers politically appropriate. It goes without saying that the extension of the territorial sea in the Aegean Sea is part of a wider political matrix that calls for careful consideration. Legally speaking, though, it would be totally lawful.

- Maritime Delimitation

Maritime delimitation is indisputably the main dispute between Greece and Turkey. As was argued above, the definition of ‘dispute’ under international law is very broad, and its existence is a matter for ‘objective determination’.[115] Accordingly, it is arguable that Greece and Turkey have not only a dispute over the delimitation of the continental shelf (and a future EEZ), but also over the delimitation of the territorial sea -especially in the Northeast Aegean Sea, where there is no delimitation treaty.

In the remainder of this Section, the legal positions of the two States concerning the issue of maritime delimitation will be succinctly set out. This will be followed by a brief, yet concise introduction to the relevant legal framework.

a) Position of Greece

Greece has a very consistent position on the matter of the delimitation of maritime zones with Turkey. Fist, with respect to the territorial sea, it is the submission of Greece that:

‘maritime boundaries between Greece and Turkey are clearly delimited. More specifically, the maritime region of the Evros estuary is delimited on the basis of the Athens Protocol of 26 November 1926; in the adjoining maritime region extending south from Evros to Samos and Icaria, in the absence of relevant agreements with Turkey, the principle of median line/equidistance applies, in accordance with customary international law…; south of Samos, between the Dodecanese and Turkey, the maritime boundaries are delimited based on the Agreement of 4 January 1932 and the Protocol of 28 December 1932, between Italy and Turkey. Greece was the successor State in the relevant provisions of these agreements, on the basis of Article 14 (1) of the Peace Treaty of 10 February 1947…; any contentions on the part of Turkey regarding the abovementioned existing status are unfounded and contravene international law. The delimitation agreements are in full force and are binding for Turkey, whereas in regions where there is no agreement on the maritime boundary, the principle of equidistance/median line is implemented based on customary law, which is valid erga omnes’.[116]

On the issue of the delimitation of the continental shelf, the long-standing position of Greece, as reflected in Greek national legislation,[117] and submitted to the United Nations and to Turkey bilaterally,[118] can be summarized as follows:[119]

-The UNCLOS and customary international law provide for exclusive rights ipso facto and ab initio of a coastal State on its continental shelf which has a minimum breadth of 200 n.m. provided the distance between opposing coasts allows this.[120]

-Islands, regardless of their size, have full entitlement to maritime zones (continental shelf/exclusive economic zone), as other land territory, a rule clearly stipulated in Article 121 (2) of UNCLOS, which reflects customary international law as confirmed by international jurisprudence. This is also confirmed by international practice, including existing delimitation agreements in the Eastern Mediterranean.

-Regarding the method of delimitation, Greece argues that the delimitation of the continental shelf or EEZ between States with opposite coasts (both continental and insular) should take place in accordance with the pertinent rules of international law on the basis of the equidistance/median line principle. More specifically, Greece refers to article 83 (1) of UNCLOS, according to which, the delimitation of the continental shelf between States with opposite or adjacent coasts shall be effected by agreement on the basis of international law, as referred to in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, in order to achieve an equitable solution. In view of Greece, ‘the jurisprudence of the international courts and tribunals on maritime delimitation affirms the central importance of the equidistance line in maritime delimitation, in the application of articles 74 and 83 of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and the corresponding rules of customary international law. This jurisprudence has developed a consistent methodology based on equidistance which has been practiced overwhelmingly by international courts and tribunals’.[121]

-In response, particularly, to the Turkey-Libya MoU, Greece claimed, amongst others, that ‘Turkey and Libya have no opposite or adjacent coasts and therefore have no common maritime boundaries. Consequently, there is no geographical and thus no legal basis to conclude a maritime delimitation agreement… In particular, …given that the insular territories of the Dodecanese islands and of Crete, lying between Turkey and Libya, belong neither to Turkey nor to Libya, but to Greece. Moreover… the inclusion of “base points” in the said memorandum, in an attempt to give a semblance of legitimacy to the purported “delimitation”, is unlawful and cannot produce any legal effect, since the projection of the coasts of Turkey on which the base points are placed overlaps with the projection of the coasts of the Greek islands…’.[122]

“More importantly, Greece contends that all islands, wherever it is situated, and not only on the ‘right side’, as Turkey claims, may have their own continental shelf/EEZ and thus they may constitute the relevant coasts upon which the median line will be drawn.”

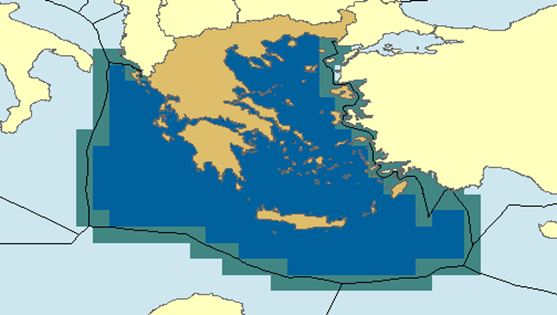

In sum, Greece’s main argumentation for the delimitation of the continental shelf)/EEZ is predicated upon the principle of median line, i.e. that the boundary should be established at the line every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points of the baselines (along the coasts) of each State (see the Greek claims based on median line: Annex II). In view of Greece, this principle is affirmed by international jurisprudence and plays a pivotal role in every delimitation case. More importantly, Greece contends that all islands, wherever it is situated, and not only on the ‘right side’, as Turkey claims, may have their own continental shelf/EEZ and thus they may constitute the relevant coasts upon which the median line will be drawn.

b) Position of Turkey

As to the alleged dispute on the delimitation of the territorial waters between the two countries, Turkey submits, first, that ‘it is a fundamental rule of international law that delimitation of maritime boundaries between adjacent and opposite states in locations where maritime areas overlap or converge should be effected by agreement on the basis of international law. In the case of the Aegean Sea, however, there exists no maritime delimitation agreement between Turkey and Greece with respect to the territorial sea in the area of adjacent coasts as well as opposite coasts’.[123]

“Turkey has never claimed that islands cannot generate maritime zones. Rather, its long-held position is that islands constitute ‘special circumstances’ and they may have reduced or no effect especially when they are ‘on the wrong side of the delimitation line’.”

With respect to the method of delimitation of the territorial sea, during UNCLOS III, Turkey presented a ‘draft article on territorial sea delimitation where it restated its preference on the application of equitable principles over the median line, stating also that the mere existence of islands constitutes a special circumstance’.[124] However, subsequently, it seems that Turkey has accepted the median line as a method of delimitation, retaining its positions on islands.[125]

On the issue of islands and whether they may have maritime entitlements, i.e. territorial sea, contiguous zone, continental shelf and EEZ, similar to the other land territory of the coastal State, it is apt to underscore that Turkey has never claimed that islands cannot generate maritime zones. Rather, its long-held position is that islands constitute ‘special circumstances’ and they may have reduced or no effect especially when they are ‘on the wrong side of the delimitation line’. For example, during the discussions on the regime of islands at UNCLOS III, Turkey -invoking the natural prolongation criterion- argued that in some regions (implying the Aegean) islands rest on the continental shelf of another state and that islands should be deemed ‘special circumstances’ in respect of maritime delimitation.[126] As Ioannides observes, ‘for the sake of clarity, it must be noted that Turkey recognised, in principle, that islands form part of the territory of a state and, hence, have a continental shelf of their own, but sought clarifications on the applicable method in terms of the designation of the sea areas where the state would exercise its sovereign rights generated from islands. Even so, Turkey attempted to deny a continental shelf to islands with a certain location, namely the Greek islands in the Aegean Sea, so as to create some kind of regional deviation.’[127]

“…islands cannot have a cut-off effect on the coastal projection of Turkey, the country with the longest continental coastline in Eastern Mediterranean”

Subsequent to the UNCLOS III, Turkey has further clarified its position in relation to the islands and their role in maritime delimitation. According to recent Letter from the Permanent Representative of Turkey to the UN Secretary-General (18 March 2020), ‘following the precedent of various judgments by international bodies of adjudication, (a) islands cannot have a cut-off effect on the coastal projection of Turkey, the country with the longest continental coastline in Eastern Mediterranean; (b) the islands which lie on the wrong side of the median line between two mainlands cannot create maritime jurisdiction areas beyond their territorial waters’.[128] On the other hand, according to Ambassador Erciyes, whose views are reproduced by the Turkish MFA, delimitation and entitlement produced by islands are not the same and ‘islands may get zero or reduced EEZ/CS if their presence distorts equitable delimitation’.[129] Also, Ambassador Erciyes asserts that ‘islands (i) cutting off Turkey’s coastal projection and CS [continental shelf] (ii) lying on the wrong side of the median line between mainlands (iii) with minimal coastal lengths comparing to Turkey’s mainland should not generate CS and EEZ’.[130]

“…refutes the median line and contends that the delimitation of the continental shelf (and the EEZ) should be effected on the basis of equity or equitable principles”

As to the method of delimitation, Turkey consistently refutes the median line and contends that the delimitation of the continental shelf (and the EEZ) should be effected on the basis of equity or equitable principles taking into account relevant circumstances with a view to achieving an equitable solution.[131] These relevant circumstances should include: the regional geography, including particular features of the region (semi enclosed sea); configuration of the coasts; the presence of islands, including their size and position in the context of general geographic configuration; non-geographic circumstances, such as historic rights and the presence of third states, as well as other factors affecting delimitation, like proportionality and non-encroachment (or non-cut-off effect).[132]

It readily appears that the two States hold diametrically opposed views on the legal rules governing maritime delimitation. In the remainder of this Section, these views will be assessed against the background of the relevant rules of international law with the view to shedding some light on the legal framework of maritime delimitation between Greece and Turkey.

c) The Relevant Rules of International Law

i) Delimitation of the territorial sea

Even though Greece does not recognize that there exists a legal dispute with Turkey on the issue of the delimitation of the territorial sea between the two States, there is merit in setting out the relevant legal rules in case such issue arises either in the context of negotiations or in judicial proceedings. Notably, it is often the case that the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and other international tribunals are called to delimit all the maritime zones of the parties, including the territorial sea, the continental shelf, and the EEZ. In those cases, the ICJ and tribunals do draw a ‘single maritime boundary’ between the parties, which, as we will discuss, may raise certain methodological concerns.

“…the ICJ has accepted that this ‘equidistance/ special circumstances’ rule represents customary international law. Also Turkey seems to accept this rule as the applicable legal framework.”

In terms of the rules on the delimitation of overlapping territorial seas, Article 15 UNCLOS provides that: ‘Where the coasts of two States are opposite or adjacent to each other, neither of the two States is entitled, failing agreement between them to the contrary, to extend its territorial sea beyond the median line every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points on the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial seas of each of the two States is measured. The above provision does not apply, however, where it is necessary by reason of historic title or other special circumstances to delimit the territorial seas of the two States in a way which is at variance therewith’. Significantly, the ICJ has accepted that this ‘equidistance/special circumstances’ rule represents customary international law.[133] Also Turkey seems to accept this rule as the applicable legal framework.[134]

As acknowledged by the ICJ in the Costa-Rica/Nicaragua case, there is an established jurisprudence, according to which the Court proceeds in two stages: first, the Court will draw a provisional median line; second, it will consider whether any special circumstances exist which justify adjusting such a line.[135] In practice, international courts and tribunals have very exceptionally departed from the median line in drawing the boundary between overlapping territorial seas. It has happened only in cases that: i) there were geographical or geological difficulties, including difficulties in identifying reliable basepoints on the coast;[136] ii) there were historical arrangements and navigational interests;[137] and iii) there was a tiny island (‘rock’ in legal terms) situated at the provisional equidistance line.[138]

It is very rare that an international court or tribunal would have only to delimit the territorial sea. On the contrary, the delimitation of the territorial sea is often only one part of the delimitation process and the question is whether the process for the delimitation of the territorial sea should be subsumed by that of an EEZ/continental shelf. This is of importance in case the ICJ or other Tribunal is called to draw a ‘single maritime boundary’, i.e. a boundary for all maritime zones, between Greece and Turkey.

In this regard, it was particularly welcome that in the most recent judgment in the delimitation case between Costa Rica and Nicaragua in the Caribbean Sea, the ICJ did, even implicitly, clarify the relevant legal framework that was gratuitously obscured by the Arbitral Award in Croatia and Slovenia case. In between, ITLOS had already taken some distance from the Croatia-Slovenia pronouncement on the delimitation of territorial sea in the Ghana v Cote d’Ivoire case.[139]

In the Croatia-Slovenia case, the Tribunal in essence assimilated the rules on the delimitation of territorial seas with those applicable to the delimitation of continental shelf/Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). The Tribunal had, amongst others, to delimit the territorial sea boundary between Croatia and Slovenia. The tribunal noted that the applicable law was Article 15 of the UNCLOS yet highlighted the similarity of the methods of delimitation for all maritime zones, which was to begin with the construction of an equidistance line and then consider whether that line required adjustment in the light of any special circumstances. In its words, ‘in relation to the delimitation both of the territorial sea and of the maritime zones beyond the territorial sea, international law thus calls for the application of an equidistance line, unless another line is required by special circumstances’.[140] In so doing, the Tribunal readily favoured the position of Slovenia in this regard and espoused the rationale of the ‘no cut-off effect’ that is more pertinent to the delimitation of the EEZ/continental shelf rather than that of territorial seas.[141]

It is submitted that this is a marked departure from the relevant provisions of UNCLOS. It is readily apparent from the face of these provisions that the territorial sea is to be delimited on the basis of the equidistance principle, unless historic titles or special circumstances call for other delimitation, while the continental shelf/EEZ is to delimited on the basis of international law with the view to achieving an equitable result. What in essence the Arbitral Tribunal did was to unwarrantedly import to the generally simple and foreseeable exercise of territorial sea delimitation all the exigencies of continental shelf/EEZ delimitation, including the disparity of the length of the coasts (proportionality), the concavity of the coastline and the concomitant principle of the no cut-off effect, the idea of natural prolongation coined in the North Sea Continental Shelf cases, and so forth. Hence, in applying the methodology used in continental shelf delimitation, the Arbitral Tribunal deviated from the strict equidistance line and gave significantly more territorial seas area to Slovenia to the detriment of Croatia. It stands to reason to assume that the result would have been different if the delimitation had proceeded as provided for under Article 15 UNCLOS.

This assumption finds significant support in the recent ICJ Judgment in the Costa Rica/Nicaragua case. In that case and in a similar vein with Croatia, Nicaragua pleaded that the law applicable to the delimitation of the territorial sea and continental shelf/EEZ is identical.[142] This of course would have been beneficial for Nicaragua, due to its more extended length of its coast and the concavity of the pertinent coastline, which leads to certain cut-off effect of its natural prolongation, especially in the Pacific Ocean.[143] However, this argument was not sustained by the Court, as it held that it is Article 15 UNCLOS that is applicable and not the regime governing the delimitation of the continental shelf/EEZ.[144]

“This is particularly welcome in respect of the Greek-Turkish dispute, since in the case that a Court or Tribunal is called to draw a single maritime boundary between all maritime zones of the two States, it would be very handy for Turkey to[…]and plead for a territorial sea delimitation along the lines of continental shelf/EEZ delimitation.”

Consequently, the recent ICJ judgment marks a return to orthodoxy and legality in respect of territorial sea delimitation and this is very commendable development. This is particularly welcome in respect of the Greek-Turkish dispute, since in the case that a Court or Tribunal is called to draw a single maritime boundary between all maritime zones of the two States, it would be very handy for Turkey to assume the position of Slovenia in the Croatia/Slovenia case or that of Nicaragua in Nicaragua/Costa Rica case and plead for a territorial sea delimitation along the lines of continental shelf/EEZ delimitation.

“…safe prognosis would seem to be that, absent any exceptional geographical instability or historic rights in the relevant maritime area, it would be difficult for a Court to depart from the median line in any future hypothetical delimitation of the overlapping territorial seas between Greece and Turkey.”

In concluding, the delimitation of the territorial sea is subject to a very clear and foreseeable legal framework under customary law, which Turkey seems to accept, in principle. Thus, a safe prognosis would seem to be that, absent any exceptional geographical instability or historic rights in the relevant maritime area, it would be difficult for a Court to depart from the median line in any future hypothetical delimitation of the overlapping territorial seas between Greece and Turkey.[145]

iii) Delimitation of Continental Shelf and the EEZ

-The Applicable Rules: In stark contrast to the rather straightforward rule on territorial sea delimitation, the UNCLOS rules on the delimitation of the continental shelf and EEZ are markedly vague. Articles 74(1) and 83(1) of the LOSC both provide that such delimitations are to be ‘effected by agreement on the basis of international law, as referred to in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, in order to achieve an equitable solution’. As Evans observes, ‘it is of next to no practical utility at all for those seeking to better understand how to delimit a boundary. As a result, it is to the work of the ICJ, ITLOS and other arbitral bodies that one must look for the articulation and development of the principles applicable under both the LOSC and customary international law’.[146]

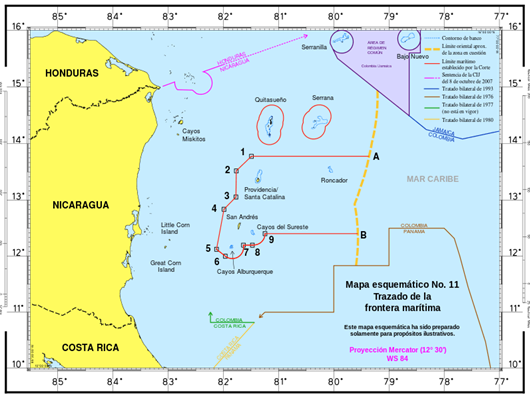

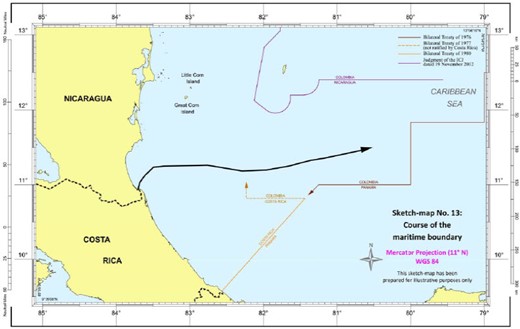

Such principles have been found after numerous twists and turns of the relevant case-law, starting from the seminal 1969 North Sea Continental Shelf cases,[147] moving to the 1985 Libya/Malta[148] and the 1993 Jan Mayen case,[149] and culminating in the 2009 Black Sea case and the ‘three stage approach’, which, arguably, offers some degree of specificity and predictability. Accordingly, courts and tribunals first provisionally draw an equidistance line using the most appropriate base points on the relevant coasts of the Parties. Second, they consider whether there exist relevant circumstances, which are capable of justifying an adjustment of the equidistance line provisionally drawn. Third, they assess the overall equitableness of the boundary resulting from the first two stages by checking whether there exists a marked disproportionality between the length of the Parties’ relevant coasts and the maritime areas found to appertain to them.[150] This acquis judiciaire is supplemented by two preliminary, yet very significant considerations, i.e. the establishment of the ‘relevant coasts’, namely those that “generate projections which overlap with projections from the coast of the other Party”,[151] and the designation of the ‘relevant maritime area’. As the Court indicated in Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v. Colombia), “[t]he relevant area comprises that part of the maritime space in which the potential entitlements of the parties overlap”.[152]

“…it is reasonable to presume that the ‘three-stage approach’, as developed by the relevant jurisprudence, would be the applicable legal framework of the delimitation of the continental shelf/EEZ between Greece&Turkey before any international court& tribunal.”

In concluding, it is reasonable to presume that the ‘three-stage approach’, as developed by the relevant jurisprudence, would be the applicable legal framework of the delimitation of the continental shelf/EEZ between Greece and Turkey before any international court and tribunal. Turkey would be difficult to contest this, and in any case, it appears that it accepts the relevant provisions of UNCLOS underlining the fact that the ultimate goal is an ‘equitable solution’.[153]

-Relevant Circumstances: It goes without saying that a key factor is which would be the relevant circumstances, if any, that a Court would take into consideration at the second stage of the delimitation process in a future case between Greece and Turkey. Relevant circumstances are an open-ended category comprising an undefined set of factors considered on a case-by-case basis.[154] Thus, there is no legal limit as to what factors can be considered as a relevant circumstance.[155] However, while there is no fixed list of relevant circumstances,[156] theory usually distinguishes between geographical and non-geographical ones, with state practice and the relevant case law according precedence to the former particularly concerning the delimitation of continental shelf and the EEZ. ‘Such a geography-centric approach is faithful to the adage that the land dominates the sea and the fact that State entitlements to maritime space derive from the coast, and are thus dictated by coastal geography’.[157]

Indeed, there is an overwhelming propensity of courts and tribunals to rely on geography-related factors in order to adjust the provisional equidistance line, with the cases in which other, non-geographical, factors have played a role being rather exceptional. Notable exceptions have been the Jan Mayen case (fisheries),[158] Nicaragua/Colombia case (‘orderly management of maritime resources, policing and the public order of the oceans in general’),[159] and older cases, like Tunisia/Libya[160] with respect to the existence of natural resources, including petroleum fields or wells within the relevant area.

Among these circumstances, it is worth having a closer look at few, which presumably would play a role in the delimitation between Greece and Turkey, in view also of the relevant position of Turkey.[161]

-Islands: It is a truism that maritime features, including islands, or according to the Award in the South China Sea case, ‘fully entitled islands’,[162] and rocks, play a significant role in maritime delimitation cases.[163] According to Article 121 UNCLOS, which reflects customary law,[164] ‘1. An island is a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide. 2. Except as provided for in paragraph 3, the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf of an island are determined in accordance with the provisions of this Convention applicable to other land territory.3. Rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf’.

As observed by the ICJ in the Nicaragua/Colombia case, all rocks, however small and insignificant, can generate a territorial sea of 12M from their baselines.[165] By contrast, any island feature that is capable of sustaining human habitation or economic life of its own will (subject to the overlapping claims of any neighbouring State) generate full EEZ and continental shelf rights.

It was only relatively recently, namely in the 2016 South China Sea Award, that the cryptic provision of Article 121 (3) was for the first time construed by an international court or tribunal. This case, even though criticized by many authorities,[166] offers us some practical guidance on how to apply the Article 121 distinction to specific features.[167] Interestingly, in the most recent ICJ judgment on maritime delimitation (Costa Rica v Nicaragua), the ICJ did not refer to the South China Sea in applying Article 121 to certain maritime features.

“When it comes to delimitation, particularly of the continental shelf/EEZ, maritime features, are taken into account twofold: first, as base points for the drawing of the provisional baseline at the first stage of the delimitation process, and second, as relevant circumstance calling for an adjustment of the provisional equidistance line.”