Rarely has an election outcome in Germany been as uncertain as it is today. Berlin’s future policy towards Ankara, and not at least the related refugee issues, especially following the recent developments in Afghanistan, will be one of the topics future coalition partners will need to agree on. The election manifestos of the political parties provide an important source for analyzing the political views of the political actors. All parties criticize the dire situation of human rights and the rule of law in today’s Turkey. While CDU/CSU and the far-right AfD reject a Turkish membership in clear terms, the other parties are less outspoken in this point. Potentially the most consequential divergence as reflected in the electoral programs relates to Germany’s arms export policy and the EU Refugee Agreement of 2016. Unlike the other parties, both the Greens and “Die Linke” want to terminate the migration deal as well as the export of German arms to Turkey.

You may read here in pdf the Policy Paper by Dr Ronald Meinardus, Istanbul-based political analyst and commentator; ELIAMEP Senior Research Fellow as of 1 October 2021.

WITH ANGELA MERKEL stepping down after sixteen years in power, a political era is coming to an end in Germany. The federal elections of September 26 will determine what happens next in Berlin. Rarely has an election outcome been as uncertain as it is today. According to the pollsters, the country may face arduous coalition negotiations. While foreign policy issues will not be the dominant concern in these, they will still play an important role. The recent events in and around Afghanistan have shown how volatile the situation is and how new and unforeseen issues can emerge overnight to dominate political debates. In this context, Berlin’s future policy toward Ankara, and not least the related refugee issues, especially in the light of the recent developments in Afghanistan, will be one of the topics future coalition partners will need to agree on.

The election manifestos of the political parties are an important source for analyzing the political views of the political actors. All the parties represented in the Bundestag make more or less extensive references to Turkey and the question of how Germany should deal with the nation.

Criticism of the prevailing state of affairs in Turkish domestic politics under President Erdoğan and the dire human rights and rule of law situation are common denominators in every party’s manifesto. Without exception, the political parties share their views on the issue of Ankara’s EU relations and, ultimately, Turkey’s prospects of joining the European Union. On this crucial point, Germany’s parties adhere to different policies: while the CDU/CSU and the far-right AfD reject Turkish membership in no uncertain terms, the other parties are less outspoken on the issue. Potentially the most consequential divergence, as reflected in the electoral programs, relates to Germany’s arms export policy and to the EU Refugee Agreement of 2016. Both the Greens and Die Linke emphasize their intention to terminate the migration deal, as well as to end the export of German arms to Turkey.

Introduction

The wording is straightforward: “A sovereign Europe, the transatlantic partnership, work to support peace and security, the promotion of democracy and human rights, and commitment to multilateralism are the guiding principles of German foreign policy”[1].

This is how Germany’s Federal Foreign Ministry welcomes visitors to their homepage. In general, all major political forces agree on these principles. As a result, foreign policy debates in Germany typically focus less on these stated fundamentals. They deal instead with how best to put the principles into practice in an international environment that is permanently changing.

This time around, however, Germany itself is contributing to the uncertainties. With Angela Merkel stepping down after 16 years at the helm of the EU’s leading power, the effect this may have on Berlin’s foreign policies is a topic governments and analysts are discussing in every part of the world.

This paper deals with Germany’s foreign policy vis-à-vis Turkey and aims to show what can be expected in this regard as the “Ära Merkel”[2] comes to an end. Given that Berlin is a key player in the European Union, the future direction of Germany’s policies regarding Turkey is of special importance for Ankara’s anything but easy relationship with the EU.

Every electoral campaign is different. In this year’s contest, Germany’s political parties have focused their campaigns on how best to cope with the lingering pandemic and on how to deal with the catastrophic effects of climate change. We are living in extraordinary times and foreign policy issues have, for obvious reasons, been relegated to a back seat – without, of course, being completely left out of the political debates, as the recent discussions relating to Afghanistan show.

Heading the list of perpetual foreign policy issues once again has been the relationship with Putin’s Russia and an increasingly assertive China, a major business partner for Germany. A recurring theme in related debates has been the future of Europe and how the European Union can be more effective at dealing with its numerous challenges in the future.

While not at the very top, Turkey has also figured prominently in German foreign policy debates – and controversies. The importance of Turkey in Germany’s international relations is reflected not least in the frequent references made to the country in political discussions, media reports, and the election programs of major political parties. As we will see, all parties refer more or less extensively to Turkey, and to how Germany should position herself vis-à-vis Ankara, in their campaign manifestos.

“Programs or platforms play an important role in Germany’s party politics.”

Programs or platforms play an important role in Germany’s party politics. The “law on political parties” (Parteiengesetz[3]) mandates that political parties lay down their objectives in political programs. In this context, election programs (or manifestos) are important. Typically published well ahead of polling day, these Wahlprogramme should not be confused with the more basic policy programs (Grundsatzprogramm) which define the ideological orientation of the party and are, as the name implies, more “fundamental” and thus long-lasting.

Both formats are the result of intensive political debates at various levels of the party which culminate in their formal adoption by a party convention. While the more ideological Grundsatzprogramm is directed primarily at the party’s rank-and-file, and aims to orientate their members and followers, the election program targets voters, which is to say the general public. In them, using simple language, the parties explain what they intend to do in the various policy areas should they come to power, or – and this a more probable scenario today – should they be part of a coalition government.

Political chromatics and the need for coalitions

Throughout her sixteen years at the helm, Angela Merkel has never ruled alone, having always shared power with a coalition partner: First, from 2005 to 2009, with the Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, SPD) in a “grand coalition.” Following that, from 2009 to 2013, with the liberal Free Democratic Party (Freie Demokratische Partei, FDP), referred to in Germany’s political chromatics as the “Black Yellow” coalition. After the Liberals’ failure to pass the five percent threshold and win representation in parliament in 2013, Merkel returned her party to its “grand coalition” with the Social Democrats.

“…the pollsters believe the electorate may deliver a result that will necessitate three parties joining hands to secure a majority in parliament.”

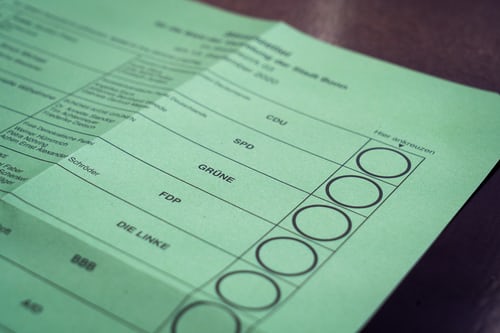

It is widely expected that there will be a shift in power following the upcoming Bundestag elections. According to numerous polls, various coalitions are possible, with no party expected to win the majority needed to form a government alone. Political observers opine that none of the former coalitions – referring to the present “grand coalition” of CDU/CSU and SPD, a Black-Yellow coalition of CDU/CSU and FDP, a social-liberal coalition of SPD and FDP, and lastly a Red-Green coalition – is likely to result this time round. All these coalitions have one thing in common – they consisted of two parties – , while the pollsters believe the electorate may deliver a result that will necessitate three parties joining hands to secure a majority in parliament.

As of the time of writing (late August 2021), the following coalitions are the most discussed:

Kenya Coalition – Black, Red, Green: CDU/CSU; SPD, Greens (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen)

Jamaica Coalition – Black, Yellow, Green: CDU/CSU; FDP, Greens

Germany Coalition – Black, Red, Yellow: CDU/CSU, SPD, FDP

Traffic Light Coalition – Red, Yellow, Green: SPD, FDP, Greens

The phraseology is based on the symbolic colors of the political parties: black for the Christian Democrats, red for the Social Democrats, yellow for the Liberals and, yes, Green for the ecological party. These same colors are found on the national flags of Kenya, Jamaica and Germany, which explains how creative minds came to develop the popular terminology.

The ups and downs of German-Turkish relations

During the long years of Angela Merkel’s rule, relations between Germany and Turkey have seen numerous ups and downs – with more downs than ups.[4]

Today, the relationship between Germany and Turkey is at a “historically low point,” write Burc, R. & Copur, B (2017, p. 7) in their assessment of Germany’s policy toward Turkey. They conclude that “To the greatest extent, the relationship of trust is shattered,” going on to compare Euro-Turkish relations to a “pile of shards”.

This has not always been the case, the authors say, referring to the period between the recognition of Turkey as an accession candidate and the beginning of accession negotiations (1999–2005). This period is also referred to as “the golden years of “Euro-Turkish relations.” Importantly, this phase coincides with a high in bilateral German-Turkish relations.

In those years, a Red-Green coalition government was in charge in Berlin. According to Rosa Burc and Burak Copur, the Social Democrat Gerhard Schröder and his Green Party foreign minister Joschka Fischer were the “driving force” behind the positive developments in Euro-Turkish affairs.

The change of government in 2005 and the coming to power of Angela Merkel of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) led to a paradigm shift in Germany’s policies toward Turkey, with wide-ranging negative implications for Turkey’s relationship with the European Union:

“The departure from the pro-active policy towards Turkey by Germany after 2005 went hand in hand with a systematic deterioration of the relationship between Ankara and Brussels,” write Rosa Burc and Burak Copur (ibid.). With this observation, the authors highlight the close link that exists between domestic political developments in Germany and the status of the relationship between Turkey and the European Union.

While the SPD and the Greens proactively supported the idea of Turkey’s membership in the EU, Angela Merkel pleaded for a “privileged partnership.” This did not bring the political process to an end, but it did slow it down considerably.

“During Merkel’s tenure as Chancellor, German-Turkish relations have experienced numerous crises.”

During Merkel’s tenure as Chancellor, German-Turkish relations have experienced numerous crises.

“The bilateral relationship has been influenced by the unresolved integration problems of some of the Turkish and Kurdish immigrants living in Germany and the overall state of human rights and democracy in Turkey,” writes Szabo (2018), referring to the assessment of Germany’s prime expert on Turkey at the time, Heinz Kramer of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, SWP). With the accession of the Republic of Cyprus to the European Union in 2004, a further disruptive factor was added to Turkey’s relations with the EU, though it would not initially have major negative side effects for German-Turkish affairs.

Recently, in the context of the crisis in the Eastern Mediterranean, we saw how a Greek-Turkish dispute – and the Cyprus question could also be perceived as a Greek-Turkish issue – could have disruptive effects on the German-Turkish relationship.

A few years back, another crisis of global proportions which would destabilize domestic politics in Germany led Ms. Merkel to readjust her foreign policy vis-à-vis Turkey – and in a positive manner from a Turkish vantage point. The government in Berlin came to the conclusion that the Syrian refugee crisis, which had already become the dominant theme in Germany, could not be managed without the close cooperation of President Erdoğan. Germany’s forceful political activities culminated in the EU-Turkey agreement on refugees of March 18, 2016.

A “strategic partner”: Turkey in the CDU’s election manifestos

Against the backdrop of the refugee deal, the Christian Democrats emphasize the important role of Turkey as a strategic partner:

“We appreciate the strategic and economic importance of Turkey for Europe […]. We want as strong as possible cooperation between the European Union and Turkey, as well as a close strategic cooperation in issues relating to foreign and security policies.” (CDU/CSU, 2017, p.58)

The rhetoric is reminiscent of statements from the Cold War era, when mainly conservative forces celebrated Turkey for its role as a bastion of the free world against the “communist onslaught.” However, the perceived threat has changed now, and communism is no longer the peril; the new challenge is how to keep millions of desperate individuals fleeing warfare and misery, and seeking protection in Europe, away from the borders. To handle this challenge, Mr. Erdoğan proved a not-always-easy, but ultimately cooperative and effective partner.

In their 2017 election manifesto, the CDU deals with Turkey in two paragraphs. The first highlights, as just seen, the strategic significance of the relationship, while the second is shorter and more straight forward: “We reject a full membership of Turkey, because the country does not meet the necessary conditions.” (ibid.) The party is worried by recent developments concerning the human rights and rule of law situation, the manifesto states.

“There will be no EU membership for Turkey with us.”

This year’s electoral platform conveys more or less the same message, while – as regards the topic of EU membership – the wording has been adjusted slightly, and in a negative manner: “There will be no EU membership for Turkey with us.” As an alternative, the party suggests a “close partnership,” whose wording is weaker, involving less commitment, than the earlier talk of a “privileged partnership.” (CDU/CSU, 2021, p. 20).

That there could be no business as usual in Berlin’s relationship with Ankara is another message conveyed in the program: “Our relationship with Turkey is in need of a new perspective.” Unlike the 2017 manifesto, the 2021 program includes a reference to NATO as an “alliance of values,” meaning that all members are obliged to respect human rights and the rule of law.

Brief and evasive: The SPD’s positions

Not least because it is the party of the foreign minister, the SPD’s programmatic positioning on Turkey deserves special attention. Titled “Out of Respect for Your Future,” the 66-page document is the shortest manifesto of all the major political parties, and the laconic nature of its remarks on Turkey, which is dealt with in just three sentences, is in tune with this brevity:

“We observe developments in the Turkish government’s domestic and foreign policy with concern. Turkey must respect the principles of the rule of law, democracy and international law. It is a matter of extreme urgency that the dialog between the EU and Turkey be intensified in order to address these issues in a critical manner.” (SPD, 2021, p. 60)

In their election manifesto of 2017, the Social Democrats allotted far more space to Turkey, which is termed “an important, but now very difficult partner.” The SPD then went on to criticize the “massive arrests” of journalists and oppositionists. As for its take on Turkey-EU relations, the SPD – unlike the CDU, with which it is in coalition – is evasive: “Neither Turkey nor the European Union are ready for accession in the foreseeable future. On the other hand, the accession negotiations are the only continuing dialog format of the European Union with Turkey. Isolating Turkey is not in the interest of Europe.” (SPD, 2017, p. 100)

This support for the continuation of the accession talks in the 2017 manifesto has been dropped in this year’s document. It should be mentioned that the SPD included one clear caveat in 2017: “Should Turkey reintroduce the death penalty, the accession negotiations must be terminated.” (ibid.)

The elections for the 19th Bundestag took place on September 24, 2017 and resulted in a crushing defeat for the incumbents. The voters punished both the CDU/CSU and the SPD severely. Never since the early days of the Republic had the traditional “people’s parties” fared so badly at the polls. The CDU/CSU won 33 percent of the votes, a decline of no fewer than eight percentage points from the previous elections. The SPD fell to 20.5 percent of the vote – five percentage points down compared to 2013[5]. As the smaller parties failed to iron out a program for an alternative coalition, Angela Merkel had little choice in the end, after much toing and froing, but to continue governing side by side with the Social Democrats.

The coalition formation process follows a standardized routine: Initially, the potential partners spend long hours, which often last deep into the night, sounding out common ground. The exploratory talks are then followed by negotiations between the party leaders, and in the end, the party rank-and-file get to vote on the results achieved by the negotiating teams. The process is also rather transparent for this same reason; in the end, the coalition partners publish their agreement – the so called coalition contract (Koalitionsvertrag) – for everyone to see.

The Koalitionsvertrag carries far more political weight than the Wahlprogramm of a specific political party, since it is the contract in which the coalition partners formulate in a binding manner the policies they intend to implement in the coming legislature. The section on future policies toward Turkey is comparatively extensive in the coalition agreement of early 2018:

“…we neither wish to open nor to close any chapters in the accession negotiations. Visa liberalization and an extension of the Customs Union are only possible when Turkey meets the required conditions.”

“Turkey is an important partner for Germany and a neighbor of the European Union with whom we entertain multifold relations. For this reason, we have a special interest in a good relationship with Turkey. The democracy, rule of law and human rights situation has been deteriorating for quite some time in Turkey. For this reason, we neither wish to open nor to close any chapters in the accession negotiations. Visa liberalization and an extension of the Customs Union are only possible when Turkey meets the required conditions.”[6]

“There is little disagreement among the political class in Germany that Turkey is a strategically important partner and that the state of human rights and the rule of law in that country are not where they should be.”

Coalition agreements are always a product of compromise. It is in the nature of such documents: both sides try to push through as many of their policies as possible, and in the end the stronger partner wins. There is little disagreement among the political class in Germany that Turkey is a strategically important partner and that the state of human rights and the rule of law in that country are not where they should be. It is interesting to note which conclusions the coalition partners drew for their prospective policies in early 2018. In the coalition contract of March 2018, they agreed to freeze the accession talks with Ankara. They also agreed that visa liberalization and the modernization of the Customs Union, both of which are important elements of the 2016 Refugee Deal, are conditional.

Taking the election manifestos into consideration, we may conclude from the wording of the contract that the CDU has prevailed. The coalition contract also determines which party gets which ministries, with the foreign ministry going once again to the Social Democrats. It is also part of the deal, however, that the Social Democrat would have to implement policies contained in the contract which may not necessarily be fully compatible with what the party had advocated prior to forming the coalition.

New contenders for power, and their policies toward Turkey

At the time of writing, it is a distinct possibility that a future government will bring three political parties together in a coalition. It is therefore worth taking a closer look at their perspectives on Turkey and future German policies.

After failing to pass the five-percent threshold in 2013, Germany’s liberal FDP party won 10.7 percent in the 2017 elections. In this year’s election manifesto, the party, as it did in 2017, talks about ending the accession talks with Ankara: “We want to terminate the EU-accession negotiations with Turkey in their prior format and put the relationship on a new basis of close cooperation in the economic and security field.” And further: “A Turkey ruled in an authoritarian fashion by President Erdoğan cannot, in the eyes of the Free Democrats, be a candidate for membership.” (FDP, 2021, p. 49)

“With reference to the Copenhagen Criteria, Germany’s Liberals set out the conditions for such talks and look into the future, stating that ‘There will be a Turkey after President Erdoğan’.”

There is no categorical rejection of Turkish membership in the program. With reference to the Copenhagen Criteria,[7] Germany’s Liberals set out the conditions for such talks and look into the future, stating that “There will be a Turkey after President Erdoğan,” and that Berlin should prepare for that and other eventualities by intensifying its cooperation with Turkish civil society.

The chances of the leftist “Die Linke” party joining a government coalition in Berlin are considered to be rather slim. Nevertheless, the party’s positions are relevant, not least since “Die Linke” has time and again initiated policy debates regarding Turkey in parliament and beyond, and could be described as the most ardent critic of Ms. Merkel’s approach.

While avoiding a clear position on the accession issue, “Die Linke” implicitly creates a linkage with the human rights and democracy situation in Turkey: “We want all present and future candidates for membership to make unconditional commitments to human rights and democracy. This is particularly the case with Turkey.” (Die Linke, 2021, p. 230)

In their manifesto, the party pleads for the cancellation of the refugee deal of 2016 and the termination of all arms export from Germany to Turkey. “We demand an immediate stop to all exports of military hardware,” the party says in its manifesto before putting this into a broader political context: “All support for NATO states which, like Erdoğan’s Turkey, disregard international law, must be stopped immediately.” (ibid., p. 231)

While the Green Party’s election campaign ran into a series of problems, most of which were of their own making and which led to a fall in its poll ratings, the group is considered a serious contender for a role in a future coalition government. In relation to discussions on Turkey, the Greens have traditionally played a crucial role in German politics. This pioneering part may also be attributed to the fact that politicians with a migration background play a more prominent role in the Greens than in other parties. This is also reflected in their electoral manifesto for the September 2021 elections.

In the introduction to a comparatively extensive section on Turkey, the party stresses the common points: “Turkey and Europe are bound together by very much more than divides the two in terms of society, culture and the economy. The relationship between Germany and Turkey is particularly close and multifaceted because of their joint migration history.” (Bündnis 90/Die Grünen, 2021, p. 230)

However, the tone changes abruptly after this conciliatory introduction. Like the other parties, the Greens also denounce the violation of human rights and the rule of law, while demanding once again a “return to political dialogue and the peace process in the Kurdish question.”

Regarding Turkey’s EU prospects, the party’s position is conditional: “The resumption of EU accession talks is our aim,” the party states, though the manifesto then goes on to say that this will only be possible “when Turkey makes a turnaround back to democracy and the rule of law.”

Another important point with potentially far-reaching implications refers to the refugee deal struck between the EU and Turkey in 2016, which the Green Party wants to scrap: “The EU-Turkey-Deal undermines the international law on asylum and must be terminated,” (ibid., p. 231) the manifesto says.

“…an issue the Greens have raised on various occasions, is the demand to stop the export of German submarines to Turkey.”

Not explicitly mentioned in the electoral program of the party, but an issue the Greens have raised on various occasions, is the demand to stop the export of German submarines to Turkey. The Greens brought this question into the public debate in 2020 against the background of rising tensions between Greece and Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean. While the government in Berlin has restricted the export of military hardware to Ankara over the years, the six type-214 submarines produced by ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems were not affected by this policy. In separate petitions in the Bundestag, both the Greens and “Die Linke” sought a revocation of the export license, but failed to obtain a majority.[8]

The Alternative für Deutschland-AfD [Alternative for Germany] party is positioned on the right wing of Germany’s political spectrum. According to pollsters and political observers, this party has no chance of joining a government after the elections. Still, for reasons of completeness, the views of this party will be presented here. In the last elections, which were also held against the background of the “migration crisis,” the AfD won 12.6 percent of the popular vote. The AfD-position on Turkey is strongly impacted by a rejection of Islam and the role of that religion in society. “Turkey does not belong to Europe culturally,” the manifesto says. In line with this, the party is against Turkey’s membership of the European Union. “The AfD demands the immediate end of all accession negotiations” (Alternative für Deutschland, 2021, p. 64).

Because of the right-wing and in parts extremist rhetoric of members of the AfD leadership, the established democratic political parties avoid and exclude any cooperation with the group in the context of forming a government. Nevertheless, some of the party’s views also find popular support beyond the core followers of the group. This is particularly apparent with regard to Turkey.

“The German public has an overwhelmingly negative view of contemporary Turkey,” writes Szabo (2018, p. 4) with reference to opinion polls according to which three fourths of Germans polled are in favor of ending the accession talks. According to a survey commissioned by public broadcaster ARD in September 2017, of those polled 84 percent rejected Turkish membership, with only 12 percent approving of it.

The drama of these numbers is revealed when they are viewed from an historical perspective. In the early years of Erdoğan’s rule, back in 2004, a whopping 54 percent of Germans favored Turkey joining the European Union, with just 35 percent opposing the option. As noted above, these were the “golden years” of Turkish-European and Turkish-German relations, and they are unlikely to return any time soon after the German elections of September 26.

Conclusion

Germany’s parliamentary elections of September 26 mark the end of a political era. After 16 years at the helm, Angela Merkel is stepping down and a new epoch is in the making.

The political programs of political parties and the policy statements of politicians play a more important role in German politics than in other democracies. A critical public and the media, as well as the Opposition, hold the political actors accountable for what they say or write. In this sense, the election manifestos at the center of this research are not random texts without political weight; they are authoritative political documents which play a substantial role, not least when the political party comes to power.

At the same time, the election programs are also one of various factors in the political decision-making process. This is even more so in the present political situation, in which – according to most predictions – forming a government will be difficult and may include not two, as has always been the case thus far, but three political parties.

As we noted at the start, Germany’s political parties all agree on the key tenets of German foreign policy. However, clear differentiations do exist on important questions–and policies toward Turkey are a point in case–, and these are also reflected in the party programs.

The German political parties concur in their criticism of the prevailing domestic and foreign policies of the Turkish government. The parties reject what they term the growing authoritarian tendencies of President Erdoğan, the violations of human rights and the undermining of the rule of law.

Differences exist as to how Berlin should react to these developments. While there is a broad agreement that the current illiberal situation should affect Turkey’s relationship with the EU, we have seen different positions expressed on what long-term perspectives the Turks should be offered. While for the CDU/CSU and the AfD, things are clear, with no place for Turkey in the Union, the other parties are less outspoken or downright evasive on this point.

“…the most striking differentiation in the electoral programs, and the one with potentially the most political consequence, relates to the parties’ policies on the issue of arms exports and the EU-Turkey refugee deal of 2016.”

Arguably, the most striking differentiation in the electoral programs, and the one with potentially the most political consequence, relates to the parties’ policies on the issue of arms exports and the EU-Turkey refugee deal of 2016. In their programs, both the Greens and “Die Linke” announce that they will scrap the refugee deal and ban the export of submarines to Turkey.

In the coming weeks and months, there will be a good deal of talk about continuity and change in German politics as the “Ära Merkel” comes to an end. The extent of the change will largely depend on the outcome of the elections and the subsequent composition of the parliament and government.

The most substantial changes regarding policies toward Turkey should be expected when the Greens – not to mention “Die Linke” – are given a mandate to play a determining role in Germany’s foreign affairs.

[1] https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/en/aussenpolitik/themen/policy-principles/229790.

[2] In a good portrayal of the “special relationship” of Angela Merkel with Recep Tayyip Erdoğan entitled “You cannot choose your partners””, German correspondent Rainer Hermann speaks of “mutual trust and respect”; Merkel perceives Erdogan in a “matter of facts and unemotional manner”, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, January 24, 2020. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/politik/ausland/merkel-trifft-erdogan-man-kann-sich-seine-partner-nicht-aussuchen-16597369.html

[3] https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/partg/BJNR007730967.html

[4] For a good summary and further references, see Szabo, S.F. (2018).

[5] https://www.bundeswahlleiter.de/info/presse/mitteilungen/bundestagswahl-2017/34_17_endgueltiges_ergebnis.html

[6] Koalitionsvertrag zwischen CDU, CSU und SPD. 19. Legislaturperiode, p. 150. https://www.bundesregierung.de/resource/blob/656734/847984/5b8bc23590d4cb2892b31c987ad672b7/2018-03-14-koalitionsvertrag-data.pdf

[7] The accession criteria, or Copenhagen criteria (after the European Council which defined them in Copenhagen in 1993), are the essential conditions all candidate countries must satisfy to become a member state. These include political criteria: stability of institutions guaranteeing democracy, the rule of law, human rights and respect for and protection of minorities; economic criteria: a functioning market economy and the capacity to cope with competition and market forces; the administrative and institutional capacity to effectively implement the acquis*; and the ability to take on the obligations of membership. https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/policy/glossary/terms/accession-criteria_en

[8] The parliamentary debate in which all the parties stated their positions on the issue of arms exports to Turkey is documented (in German) at Deutscher Bundestag. 19. Wahlperiode, 207. Sitzung, January 29, 2021, https://dserver.bundestag.de/btp/19/19207.pdf, p. 26180 – 26205.

Sources:

Alternative für Deutschland (2021). Deutschland. Aber normal. Programm der Alternative für Deutschland für den 20. Bundestag.

Alternative für Deutschland (2017). Wahlprogramm der Alternative für Deutschland für den Deutschen Bundestag.

Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (2021). Bundeswahlprogramm 2021. Bereit, weil Ihr es seid.

Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (2017). Bundestagswahlprogramm 2017. Zukunft wird aus Mut gemacht.

CDU/CSU (2021). Das Programm für Stabilität und Erneuerung. Gemeinsam für ein starkes Deutschland.

CDU/CSU (2017). Regierungsprogramm 2017–2021. Für ein Deutschland, in dem gut und gerne leben.

Die Linke (2021). Zeit zu handeln! Für soziale Sicherheit, Frieden und Klimagerechtigkeit. Wahlprogramm zur Bundestagswahl 2021.

Die Linke (2017). Sozial. Gerecht. Frieden. Für alle. Die Zukunft, für die wir kämpfen. Wahlprogramm zur Bundestagswahl 2017.

Freie Demokraten. FDP (2021). Nie gab es mehr zu tun. Wahlprogramm der Freien Demokraten.

Freie Demokraten. FDP (2017). Denken wir neu. Das Programm der Freien Demokraten zur Bundestagswahl 2017.

SPD (2021). Aus Respekt vor Deiner Zukunft. Das Zukunftsprogramm der SPD.

SPD (2017). Zeit für mehr Gerechtigkeit. Unser Regierungsprogramm für Deutschland.

References:

Burc, R. & Copur, B. (2017). Deutsche Türkeipolitik unter Merkel: eine kritische Bilanz, Notes du Cerfa, Nr. 140, Ifri.

Güzeldere, E.E. (2020): German-Turkey Relations: It could be worse, Eliamep Policy Paper Nr 49.

Kundani, H. (2021). Germany and Turkey after Merkel, InBrief Series, Berlin Bosporus Initiative.

Szabo, S.F. (2018). Germany and Turkey: The unavoidable Partnership, Brookings Turkey Project Policy Paper Nr. 14.

Turhan, E. (2013). The 2013 German Federal Elections: Key determinants and implications for German-Turkish relations, IPC-Mercator Policy Brief. (Submitted August 18, 2021)