How can we get small firms to work together in order to achieve mutually beneficial outcomes, despite adverse circumstances? This policy paper provides an answer to this question that could be useful both to policymakers and to local stakeholders seeking to undertake innovative, cooperative economic activities in their area. Based on evidence from eight case studies within the Greek agri-food and tourism sectors, I argue that a small group of local actors, whom I call ‘institutional entrepreneurs’, usually play a key role in catalysing the emergence of cooperation at the local level. Their strategies and experiences carry valuable insights. I also outline the characteristics that macro-level institutional frameworks need to have if they are to facilitate local cooperation. These characteristics can inform the design of institutions at both the domestic and the EU level. The paper’s findings could be relevant to people interested in local development, but also to those concerned with boosting the productivity and export orientation of the Greek economy as a whole. After all, cooperation can improve the performance of small firms, and it is thus an important ingredient for inclusive growth in countries with a lot of small firms, such as Greece.

Read here in pdf the Policy paper by Kira Gartzou-Katsouyanni, ESRC Postdoctoral Fellow, European Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science.

Cooperation and local development in fragmented economies

Greece is a country with many small firms and many small farms: fragmented ownership structures are a defining characteristic of its economy.[1] Even if the number of large firms in Greece increases in the future, chances are the country will continue to have a comparatively high percentage of small firms for decades to come. As in other similarly structured economies around the world, the abundance of small enterprises creates opportunities, but also gives rise to challenges. Large firms often enjoy lower unit costs than small firms for activities ranging from design to production, distribution and marketing, as they benefit from economies of scale. Large firms also have more power. This puts them in a better position to shape their input and output markets to their benefit, for example by persuading a local education provider to teach skills relevant to their production process, or by influencing the regulatory standards applicable to their sector. Such factors tend to generate a productivity gap among small and large firms. Supporting small firms so they can become more productive is therefore an important goal for economic policy in countries with fragmented ownership structures.

Inter-firm cooperation is therefore an important ingredient for inclusive growth in countries with many small firms.

Cooperation is one way for small firms to mitigate the disadvantage of their size and boost their productivity. By working together, small firms can collectively acquire infrastructure that they could not afford individually, meet bigger orders, and build a reputation based on place rather than their individual brand name. Acting collectively, small firms can also acquire more power to lobby policymakers and increase the availability of local employees. Inter-firm cooperation is therefore an important ingredient for inclusive growth in countries with many small firms.[2] Cooperation has never been more important for Greece in particular: since the country’s traditional inward-oriented growth model based on big public spending collapsed during the Eurozone crisis, enhancing Greek firms’ competitiveness and export orientation has been crucial for future prosperity.[3]

However, cooperation is often difficult to achieve. Even if every local firm would eventually benefit from the provision of a collective good, they may not initially trust other firms’ commitments to contribute to it, they may disagree over strategy and the sharing of costs, and they may not even fully grasp the potential benefits of the collective good before it is realized. Such obstacles are particularly difficult to overcome in Greece. Greek institutions have well-documented deficiencies that make cooperation harder: laws are not implemented uniformly, the judicial system is slow and ineffective, and hyper-centralisation coupled with clientelistic practices decrease the opportunities local firms have for productive, non-partisan deliberation and for taking local initiatives. Greece also scores low on surveys that measure interpersonal trust: in a recent survey, the share of respondents who agreed that most people can be trusted was 24% in Greece, compared to an EU average of 47%, 58% in Germany, and 85% in Finland.[4]

How can small firms operating in institutionally weak, low-trust environments overcome these obstacles to cooperation? In this policy paper, I present some key findings from my Ph.D. dissertation that address this question.[5] These findings could be of interest both to local stakeholders seeking to trigger cooperation in their area, and to policymakers interested in boosting the productivity and export orientation of Greece or other, similar economies. In the first part of the paper, I argue that a few local actors, whom I call institutional entrepreneurs, play a key role in triggering the gradual emergence of cooperation at the local level. I outline the strategies that such institutional entrepreneurs have used in real-world settings to establish trust and create a conception of shared interest around a novel entrepreneurial vision. In the second part of the paper, I zoom out to the macro level and provide an account of the characteristics that overarching institutional frameworks need to have, if they are to facilitate local cooperative efforts. I focus on specific examples of sectoral policies, provided by both the EU and Greece, and examine how they have impacted on the opportunities for local inter-firm cooperation.

The Ph.D. project on which this policy paper draws examined the emergence of cooperation in unfavourable circumstances using case studies. It relied on qualitative empirical evidence collected through fieldwork in four areas of Greece where specific types of cooperation were observed between 1980 and 2019; this evidence was then compared to data from otherwise similar (matching) areas where such patterns of cooperation failed to occur. The project focused on agri-food and tourism, two sectors that are crucial for economic development in many rural areas around the world. The case studies included the wine sectors of Santorini and Lemnos, the mastiha sector of Chios, the saffron sector of Kozani, alternative tourism in the villages of Nymphaio and Ambelakia, and mass tourism in Santorini and Chalkidiki. The findings were based on 86 semi-structured interviews with local stakeholders, documentary evidence, the local press, and secondary literature about the case study areas in question. Some of the dissertation’s findings were also examined quantitatively, while their applicability beyond Greece was explored using empirical evidence from two case studies in Southern Italy.

Triggering change at the local level: the role and strategies of institutional entrepreneurs

In the mid-1980s, a “climate of deep mistrust” characterised relations between producers and the management board at the cooperative on Chios which specialises in the sale of mastiha, the resin of the local mastic trees.[6] The cooperative was heavily in debt, and its repeated failure to pay producers in full had led to a large decrease in the quantity of the mastiha produced and a growth in the black market. As a producer put it in a General Assembly meeting of that period: “The deficits are exasperating. We don’t even feel like collecting the mastiha from the trees when the management board is in such a state of disarray. How are we supposed to believe you and trust you to sell our mastiha?”[7] Fast-forward thirty years, and the mastiha cooperative has become “an example of the tremendous potential of Greek co-operatives”.[8] The innovative retail stores of the cooperative’s subsidiary company, MastihaShops, “have contributed to many people with an enquiring mind across Greece revisiting what we call a Greek traditional product from the ground up: how to remake it, how to package it, how to groom it.”[9] In the meantime, mastiha has been transformed from a purely local affair into one of Greece’s most recognisable agri-food products. How did this remarkable change come about?

A small group of leading actors can play a key role in catalysing the emergence of innovative, cooperative economic activities in settings where non-cooperation was formerly the norm.

A small group of leading actors can play a key role in catalysing the emergence of innovative, cooperative economic activities in settings where non-cooperation was formerly the norm, such as Chios. Following Crouch, I call such actors, who succeed in overcoming the constraints of path dependence to bring about institutional innovation, “institutional entrepreneurs”.[10] As prominent individuals whose actions are particularly visible to other local actors, institutional entrepreneurs introduce cooperative norms, new conceptions of shared interest, and local institutional arrangements that promote cooperation. Their actions, which are initially perceived as unusual, gradually bring about a shift in local actors’ expectations, until cooperation becomes a more commonly observed behaviour.[11] Institutional entrepreneurs also discover and disseminate new entrepreneurial opportunities that rely on local cooperation. Discerning a novel entrepreneurial opportunity requires specific combinations of idiosyncratic prior knowledge, which only a few individuals, if any, are likely to possess.[12] Thus, a small number of boundary-spanning actors can make a major difference by introducing innovative ideas for collective entrepreneurial strategies which may never have occurred to other local actors. Finally, institutional entrepreneurs with a bigger stake in the economic future of their area are more likely to cover a significant share of the upfront costs of cooperation, which are often substantial. They can do this by investing their own effort and funds, by taking the risk of adopting cooperative strategies before others do, and by finding ways to access external funding, whether it is provided by the public or the private sector. In the absence of institutional entrepreneurs, a multiplicity of actors, each of whom has a relatively small amount to gain once cooperation yields its positive results, may find it harder to assemble the resources required to kickstart a cooperative effort. [13]

The strategies that institutional entrepreneurs have used in real-world contexts to build trust, disseminate innovative ideas, and cover the upfront costs of cooperation carry valuable lessons for other places.

The relative importance of these types of contributions, and the concrete strategies that institutional entrepreneurs employ to make them, depend on the sector. The strategies that institutional entrepreneurs have used in real-world contexts to build trust, disseminate innovative ideas, and cover the upfront costs of cooperation carry valuable lessons for other places. While “there is no one simple recipe for success (…) there are detailed tools and techniques for action that institutional entrepreneurs can study, select, and combine, depending on the case.”[14]

Upgrading quality in the agri-food sector often requires building trust among the agri-food entrepreneurs who process the raw inputs and the producers who cultivate them. According to Fritz Bläuel, a pioneer in the production of organic olive oil in Greece, “Trust is the main asset for changing the ‘software’ of the farmers”: it was primarily through incrementally building trust that he convinced a group of olive producers in a remote village in Mani to overcome their hesitation and switch to organic olive cultivation in the early 1990s, despite the short-term costs. Bläuel defines trust as “doing what you promise to do. When it comes to the farmers, trust means paying them on time, and paying them well”. He recounts: “I established trust-based relations gradually over the years, before I started with organic cultivation. (…) I started by buying conventional oil, and I acquired a reputation for paying the farmers on time. I spent ten years establishing friendships and trust.”[15] By earning the producers’ trust one step at a time, and progressively moving to more demanding forms of cooperation, Bläuel was able to create a network of organic olive producers years before a market for organic olives developed in Greece.

In the late 1980s, when he decided to produce wine in Santorini, northern Greek winemaker Yannis Boutaris wanted to introduce major changes in the way the local grapes were grown, so his wine would better suit the tastes of modern consumers. This endeavour required cooperation with the island’s grape producers, but Boutaris was initially greeted with suspicion on Santorini: as one of the producers’ representatives wrote in a letter to the wine cooperative’s General Assembly in 1989: “Let all the producers understand that Mr. Boutaris came to Santorini so that he can make money while they work. If [the suggested grape price] is not in his interest, he should close down his factory and leave.”[16] Like Bläuel, Boutaris established his credibility gradually, by sticking to his promises about better prices, by going out of his way to provide information about his plans, and by making a major investment in a new winery on Santorini that demonstrated the long-term nature of his commitment. Given that there were considerably more grape producers on Santorini than there were olive producers in Bläuel’s network, Boutaris also introduced rules to reward desirable improvements in cultivation methods and punish sub-standard production: “We were the first winery in Greece to implement a method of paying producers which was not based entirely on alcoholic degrees, but also on yield”[17] (lower yields are associated with higher quality). Boutaris’s work to upgrade Santorini’s wines had ripple effects across the local wine sector. The management board of the wine cooperative had its own modernising impulses, but Boutaris’s investment gave it the momentum it needed to construct an ultra-modern new winery. A number of oenologists from Boutaris’s firm, most notably Hatzidakis and Paraskevopoulos, would in time establish new pioneering wineries of their own on Santorini, leaving their mark on the sector.

Improving the quality of the raw mastiha was also important on Chios, but the mastiha cooperative faced an even greater challenge: it had to create new and reliable markets for mastiha, whose traditional clients in the Middle East had switched to cheaper substitutes. Starting in 2001, the cooperative revamped its strategy to that end: the central idea was to create a series of innovative, differentiated products using mastiha as an ingredient. These would be promoted at home and abroad through a network of MastihaShops, which would be run by a newly-founded subsidiary of the cooperative. The effort was spearheaded by Yannis Mandalas, who was hired to reorganise the cooperative and later became the CEO of its subsidiary, and Kostas Ganiaris, the then President of the cooperative. The cooperative’s work was reinforced by the efforts of certain private firms, such as Concepts SA, which pioneered the production of the now highly popular mastiha liqueur.

Implementing the cooperative’s new strategy required, firstly, that the producers who were its members were convinced that the benefits of founding a subsidiary company and investing in a novel entrepreneurial strategy were greater than the risks. To achieve that, Mandalas explains that he demonstrated the benefits of his plan incrementally:

“Very quickly I realised that if I didn’t have any victories at the start, let’s say in the first six months or in the first year, everything I suggested would remain a good, well-written idea in an office drawer. When I realised this, I proposed setting up the MastihaShops. (…) One year later, the subsidiary company was founded, and the first shop opened. And truly, the shop was such a success, it precipitated everything else. It precipitated the reorganisation, and the belief that, you know, things can change, a wind of optimism. This victory also limited negative reactions to the crux of the matter, which was the reorganisation of the cooperative.”[18]

Ensuring that a novel collective entrepreneurial project yields small, low-cost successes early on can be crucial for getting the relevant actors to back more costly forms of cooperation later.

Thus, ensuring that a novel collective entrepreneurial project yields small, low-cost successes early on can be crucial for getting the relevant actors to back more costly forms of cooperation later.

However, the cooperative didn’t stop at securing the producers’ backing for its new strategy: from early on, the cooperative’s leadership took the view that some private firms could also contribute to the creation of new markets for mastiha. To create a conception of shared interest horizontally in the mastiha sector, the cooperative used its MastihaShops not only as a means of selling its own final mastiha goods, but also as “a marketing tool to communicate the different uses of mastiha”, no matter who was processing it. As Mandalas explains, “What’s our aim? To sell mastiha at the best possible prices, in order to increase the producers’ income. (…) What do we do in practice? We spread ideas. (…) What I want to say is that we also protect the competition. We don’t try to monopolize the situation.”[19] By guaranteeing the quality and authenticity of raw mastiha, the cooperative also demonstrated in practice that it was a useful ally to other firms interested in producing high-quality mastiha products. My conversation with the CEO of the private firm that pioneered the large-scale production of mastiha liquor was telling in this regard. When I asked him what he thought of the fact the cooperative has a monopsony over raw mastiha, he replied: “[this] only affects us positively. It guarantees that someone gives us a specific quality, and at the same time it guarantees that others won’t find a poorer-quality ingredient and ruin the market.”[20] The CEO went as far as to characterise the method of governance of the cooperative, including the obligatory character of the mastiha producers’ membership in it, as “exceptional”. Coming from a private firm, this assessment is a testament to the cooperative’s success in forging a conception of shared interest among a broad range of actors in the sector.

Actors with substantial outside experience have an advantage: they have been exposed to a wider range of norms, institutions, markets, and ways of doing things than actors who have spent most of their life in one place.

One of the interesting recurring patterns regarding the type of actors who become institutional entrepreneurs is that they tend to be either outsiders who do not originate from the place in question and have spent most of their lives elsewhere, or hybrid actors who are local in origin but lived elsewhere for a sizeable part of their lives. Boutaris, who is from northern Greece and started his winemaking business in the north, is a typical example of an outsider as far as his activities in Santorini are concerned. As an Austrian who moved to the Mani, a remote and conservative area, Bläuel was not just an outsider, but so different from other local stakeholders that his success in forging the first network of organic olive producers in the country appears particularly surprising at first sight. Mandalas is a hybrid actor, a Chiot who studied and worked for several years in Athens before returning to the island. One might be inclined to think that local actors have a higher chance of initiating cooperation, as they are well-acquainted with local social norms, they are known and potentially trusted in their local societies, and they are more likely to have a deep knowledge of local resources. However, as we have seen, it is possible for hybrid actors and outsiders to construct cooperative norms and familiarise themselves with local resources within a few years, provided that they adopt appropriate strategies and expend the necessary time and effort. In fact, actors with substantial outside experience have an advantage over insiders that is highly valuable for the role of institutional entrepreneurs: they have been exposed to a wider range of norms, institutions, markets, and ways of doing things than actors who have spent most of their life in one place. They can draw on this broader repertoire to introduce innovation in terms of what is produced in a place, how it is produced, and which local norms and institutions surrounding the production process are adhered to. Viewed from that angle, actors who are “located at interstices”,[21] at the boundary between the local and the translocal, are better placed to catalyse the emergence of inter-firm cooperation in places where it was previously lacking.

Macro-level institutions as facilitators of local cooperation

Santorini is an “island of contrasts”.[22] It is a small island of 73 square kilometres and 15,000 inhabitants which welcomes 1.5 million tourists per year,[23] and yet, alongside thousands of tourism businesses, it also has a substantial agricultural sector with three Protected Designation of Origin products. The island features some of the highest-quality wines, restaurants and small luxury hotels in the country, and yet, as soon as visitors venture out into the island’s public space, they face urban-style problems such as traffic, pollution, overcrowding, and dirt. Santorini’s winemakers and grape producers consistently produce some of Greece’s highest quality and most expensive wines, and yet, in a substantial part of the island, the anarchic way in which the tourism industry has developed, without an overarching plan or rules, creates an image of an undifferentiated, low-quality, degraded mass tourism destination: “Whoever is honest gets tormented, whoever breaks the rules is king.”[24] How can these contrasts be explained?

The macro-level institutional frameworks that regulate economic activity in specific sectors profoundly affect the likelihood of cooperation at the local level.

The macro-level institutional frameworks that regulate economic activity in specific sectors profoundly affect the likelihood of cooperation at the local level. Overarching institutions cannot impose cooperation from above: as we have seen, the emergence of local cooperation requires the activation of institutional entrepreneurs and the broader local society. Nevertheless, by shaping the incentives and constraints that firms face, macro-level institutions can increase or decrease the obstacles to local cooperation, with major implications for the final extent of cooperation observed. In Santorini, the macro-institutional framework that applies in the agri-food sector facilitates cooperation, while overarching institutions in the tourism sector undermine it. This helps explain some of the contrasts that we observe on the island, though other factors, and especially the larger number of firms operating in tourism, undoubtedly also play a role.

How exactly can macro-level institutions facilitate the emergence of local cooperation? Firstly, they can provide incentives for economic actors to adopt rules that define and encourage cooperative behaviour in the local sector in question. The substantive content of those rules of cooperation should be determined by local actors, not by the state. Distant state officials are unlikely to have enough information about local conditions to decide on appropriate local rules. Moreover, if such decisions are taken top-down, local stakeholders may be tempted to devote their efforts to winning special favours from the central government, rather than working with other members of their community to increase the overall size of the local pie.[25] In contrast, institutions that require local actors to come together and take decisions jointly about the governance and future of their sector can help those actors come to see their common interests in a new light. This can result in benefits from cooperation that extend even beyond the adoption of the local rules.[26]

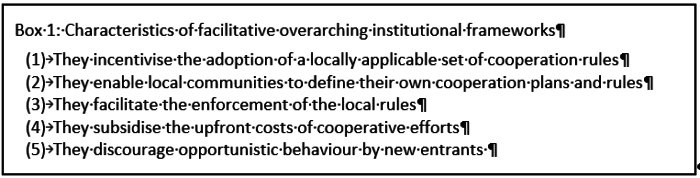

Moreover, overarching institutions can facilitate the enforcement of the local rules that have been agreed upon. This is important, as unenforced rules rapidly lose their credibility. Macro-level policies can also subsidise the upfront costs of local cooperative efforts. This can make a difference, as the costs that arise early on in a cooperative project are particularly difficult to cover locally: the stakeholders concerned will be most reluctant to contribute their resources to a collective effort before they see the benefits of cooperation starting to materialise. Finally, overarching institutions can make it harder for new firms to opportunistically enter a local sector and undermine local cooperative efforts. Local actors will be more likely to invest the effort and resources necessary to kickstart a cooperative activity if they know that new entrants will be required to abide by previously agreed rules and to contribute to ongoing collective projects. Box 1 summarises these institutional possibilities. Taken together, they define the characteristics of overarching institutional frameworks that facilitate local cooperation.

The EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) performs the functions of an overarching institutional framework that facilitates local cooperation, especially in highly regulated sectors such as wine.

Although we don’t usually think about it in these terms, the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) performs the functions of an overarching institutional framework that facilitates local cooperation, especially in highly regulated sectors such as wine. For one, the CAP’s system of geographical indications is a sophisticated tool for incentivising local economic actors to adopt their own cooperation rules. Geographical indications, such as the EU’s Protected Designations of Origin (PDO), are labels granted to products with particular characteristics that are linked to their geographical origin.[27] To be granted a PDO label, a local wine must comply with rules about its “principal analytical and organoleptic characteristics” and the “specific oenological practices” used to produce it. A PDO wine’s rulebook also has to include, among other elements, “the demarcation of the geographical area concerned”, “the maximum yields per hectare”, and the grape varietals used in the wine.[28] Those rules are not imposed from above, but are agreed upon during the process of preparing a PDO application, which can only be submitted by a “group” of economic actors, not by an individual winemaker.[29] In the words of the President of Santorini’s wine cooperative, the PDO label is important because “it requires that you are organised, that you have all those elements we lacked until then: the creation of institutions, services, rules.”[30]

Importantly, the EU’s geographical indications system also requires member-states to set up a dedicated domestic administrative structure that can guarantee the enforcement of local production rules. For a winemaker to acquire PDO labels for the wine bottles produced during a specific period, the following procedure is followed:

“When delivering the grapes, the producer must say from which vineyards they originated, so that traceability is retained. This is fundamental for quality, but also to ensure that non-vinifiable varietals are not vinified, and to prevent adulteration. (…) When the wine is ready (…) we take samples, and we send them to the Centre for the Protection of Plants and Quality Control in Patras for the chemical analysis to be done. We check particular aspects of the wine, e.g. the acidity, which must be at specific levels for the wine to be PDO. (…) Secondly, another control is performed by a committee of the Interprofessional Organisation of Vine and Wine, which is an organoleptic control.”[31]

Thus, compliance with the local wine’s rulebook is ensured through multiple layers of controls. An enforcement capacity of this sort is crucial for preventing cheating in low-trust contexts.

By favouring collective endeavours, several of the CAP’s subsidy programmes also encourage local actors to engage in cooperative activities. Such incentives played an important role in triggering cooperation among Santorini’s winemakers during the Eurozone crisis. Faced with a collapse in domestic demand for luxury wine, the Santo Wines cooperative and the island’s private wineries engaged in a concerted effort to boost their exports to the North American market. According to a representative of the cooperative, it was “when the [CAP] funding for promotion activities to third countries arrived” that a promoter of the Greek wine sector in the United States said, “It’s a pity, Santorini is very important, make sure you get organised, create a team with a contract.” More generally, “the EU has always, and increasingly as time goes by, prioritised and chosen team projects. The more collaborative they are, the better.”[32]

Finally, the CAP’s planting rights system requires new entrants in a local grape sector to abide by the rules agreed about the varietals that can be planted in the area. According to an oenologist in Santorini, the fact that “you cannot bring other, [higher-yield] varietals of grapes to plant in Santorini” is one of the most impactful aspects of agricultural legislation today, as it decreases the cases of adulteration, “where the [local] Assyrtiko varietal is mixed with another varietal that is cheaper.”[33]

Despite the dominant role small firms play in the country’s tourism industry, Greece’s domestic institutional framework is largely unsuited to facilitating cooperation among economic actors.

In contrast to the agri-food sector, tourism is mostly regulated at the domestic rather than the EU level. When a local tourism industry relies heavily on small and medium-sized enterprises, inter-firm cooperation can promote an upgrade in quality, create attractions that will diversify the tourism product and lengthen the tourism season, limit overtourism, and better manage the public goods that make a place attractive to visitors.[34] Nevertheless, despite the dominant role small firms play in the country’s tourism industry, Greece’s domestic institutional framework is largely unsuited to facilitating cooperation among economic actors.

The state does not provide a framework that encourages local actors in the tourism industry to adopt their own rules about quality or explore other areas of potential cooperation. Private actors have on some occasions attempted to create quality labelling systems of their own, but it is difficult to establish such systems at a large scale without the administrative and financial backing of the state: “Communicating a local quality label requires a good deal of money to imprint it on the consumers’ consciousness.”[35] According to one of the pioneering entrepreneurs in Santorini’s luxury and conference tourism sector, delegating real decision-making power to local inter-firm associations is the key for increasing participation in such associations: “For example, if we have an evaluation system [for local businesses], the evaluator should be the collective institution. (…) But we don’t do this, because we want to maintain our clientelistic relationship with central government, with MPs.”[36] During my fieldwork in Santorini in 2018-2019, local stakeholders communicated feeling powerless to even request the adoption of a plan regulating land uses in Santorini. Many areas in Greece are not covered by a spatial plan, and initiating the process of adopting such a plan for a specific location requires a decision by the central government; in the case of Santorini, this decision had been pending for decades.

The Greek state’s notoriously deficient enforcement capacity aggravates the situation. […] Part of the problem stems from the state’s weak administrative structures, some of which were furthered weakened during the Eurozone crisis.

The Greek state’s notoriously deficient enforcement capacity aggravates the situation. The imperfect implementation of existing rules creates the perception of an uneven playing field and a sense of inescapable anarchy: “You can’t bring order to this place, everyone does whatever they like. Solar boilers for example are not allowed in Santorini. But if someone goes and installs a solar boiler, who will take it down?”[37] Part of the problem stems from the state’s weak administrative structures, some of which were furthered weakened during the Eurozone crisis. According to a stakeholder in the rental rooms sector in Chalkidiki, who was talking about the situation in 2017, the ability of both the National Tourism Organisation and the tourism police to control the implementation of applicable rules in the tourism industry had declined markedly in recent years.[38] The hyper-centralisation of the Greek state aggravates the problem further: the failure to involve local stakeholders in rule enforcement constitutes a missed opportunity to improve the application of the law. In Santorini, the municipal company Geothira had developed an innovative approach to monitoring whether businesses offering sunbed and beach bar services had respected the space restrictions foreseen in their contract with the municipality, or if they had expanded illegally into public space at the beach where they operated. The approach was based on the use of satellite images, which “constitute fair and indisputable evidence as to the situation on the beach on a particular date.”[39] However, in 2017, without any consultation at the local level, the national government legislated that municipal companies were no longer allowed to manage beaches in Greece, and this monitoring work was abruptly ended.

Finally, the constant arrival of new entrants who cannot even be identified, let alone compelled to contribute to local cooperative efforts, makes it even harder to reach local agreements about upgrading quality and providing public goods in the tourism sector. Short-term rentals are exceptionally underregulated in Greece, compared to other European countries. In fact, in 2017 when I did my fieldwork in Chalkidiki, the Greek state did not even have a functioning system in place for real estate owners to declare any income obtained from short-term rentals to the tax authorities. This meant that a significant part of the short-term rental sector remained largely untaxed, giving it an artificial competitive advantage over established firms offering accommodation.[40] The lack of a spatial plan in many tourist areas also fuels unregulated entry into the tourism sector, as incoming firms have to comply with relatively few rules about where they can build and how they can operate in a touristic destination.

Policy implications

Inter-firm cooperation is an important economic policy goal in countries with fragmented ownership structures, as it can help small firms mitigate the productivity disadvantages associated with their size. Local cooperation can emerge despite unfavourable circumstances, if local institutional entrepreneurs implement specific strategies within a broader framework of macro-level institutions facilitating cooperation.

The concept of facilitative overarching institutional frameworks can help in the design of policies with positive developmental effects in economies with many small firms.

Policymakers can directly influence the extent to which macro-level institutions facilitate or obstruct cooperation among economic actors within specific sectors. The concept of facilitative overarching institutional frameworks, developed in the third section of this policy paper, can help in the design of policies with positive developmental effects in economies with many small firms.

Since I conducted my fieldwork, the Greek state has made progress in some of the areas I identified then as inhibiting cooperation in the tourism sector. Nevertheless, there is still considerable scope for domestic macro-level institutions to become more facilitative with regard to local cooperation. Policymakers must create venues where local economic actors can take decisions collectively about matters that affect them. The challenge is to achieve a broad-based participation in such venues, and to shield them from being taken over by party politics and clientelistic networks. An examination of the institutional models followed in coordinated market economies such as Germany and Austria could be useful in this regard. Facilitating cooperation also requires improving the state’s capacity in rule implementation, not only through reform of the justice system, but also through the setting up of appropriate administrative structures.

The concept of facilitative overarching institutional frameworks is also relevant for EU policymakers, as boosting productivity and promoting local development are central goals of EU policy. We have seen that the Common Agricultural Policy’s system of geographical indications, as well as several of its subsidy programmes, have been remarkably effective at encouraging cooperation in the agricultural sector. Thinking creatively, is it possible to replicate some of those results in other sectors? Can the EU’s cohesion policy foster local alliances more successfully if it adopts the characteristics of a facilitative overarching institutional framework? To what extent did the policies in the Memorandums of Understanding between Greece and its lenders during the Eurozone crisis facilitate inter-firm cooperation as a means of improving productivity?

While facilitative overarching institutional frameworks can be created through policy design, policymakers cannot simply supply places with successful institutional entrepreneurs. The combination of experience and motivation that enable specific actors to not only succeed in their individual roles, but also to carry an entire local sector with them in that success, occur rarely and spontaneously: they cannot be imposed from above. Nor should the state attempt to identify potential institutional entrepreneurs and support them as such, because it is very difficult to tell in advance which actors are suitably equipped for this role. Instead, policymakers can only hope to increase the probability, indirectly and in the long term, that institutional entrepreneurs will emerge in particular places–for instance, by encouraging local actors to participate in translocal networks and gain some experience outside their place of origin. While some actors who benefit from these networks and opportunities will seek better life chances elsewhere, a few may make it their goal to demonstrate that a different path to prosperity is possible in their area—one that requires synergies. Ultimately, this is how cooperation can begin to emerge against the odds.

[1] The share of persons employed in Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) in Greece is 87.9%, compared to an EU average of 66.6%. SMEs produce 63.5% of the total value added in the Greek economy, compared to an EU average of 56.4%. See European Commission, “2019 SBA Factsheet: Greece”.

[2] The importance of cooperation for economic development has been emphasised in a long line of academic literature. Indicatively, see: North, D. (1990) Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; Ferguson, W. (2013) Collective Action and Exchange: A Game-Theoretic Approach to Contemporary Political Economy. Stanford: Stanford University Press; McDermott, G. (2007) ‘The Politics of Institutional Renovation and Economic Upgrading: Recombining the Vines that Bind in Argentina’, Politics & Society 35(1): 103-43.

[3] See also: Caloghirou, Y., A. Tsakanikas, A. Chatziparadeisis and N. Kanellos (2012) ‘Cluster Policies and Observed Cluster Developments in Greece’, Deliverable D2.4.1, AEGIS project.

[4] Special Barometer 471, published by the European Commission in April 2018. On the institutional and cultural characteristics that make Greece an unfavourable environment for cooperation, see also: Doxiadis, A. (2014) Το αόρατο ρήγμα: Θεσμοί και συμπεριφορές στην ελληνική οικονομία [The invisible rift: Institutions and behaviours in the Greek economy]. Athens: Ikaros.

[5] Gartzou-Katsouyanni, K. (2020) ‘Cooperation against the Odds: A Study on the Political Economy of Local Development in a Country with Small Firms and Small Farms’, Ph.D. dissertation. London: LSE. Available at: http://etheses.lse.ac.uk/4307/

[6] Tsouhlis, D. (2011) ‘Ένωση Μαστιχοπαραγωγών Χίου και Μαστιχοπαραγωγοί: Πολιτικές Διαχείρισης του Περιβάλλοντος και του Τοπίου μέσα από την διοικητική πολιτική της ΕΜΧ (1939-1989)’ [Union of Mastiha Producers of Chios and Mastiha Producers: Policies for the Management of the Environment and the Landscape through the Administrative Policy of the Union of Mastiha Products of Chios (1939-1989)], Ph.D. dissertation. Mytilene: University of the Aegean, p. 185.

[7] Quoted in Tsouhlis (2011), pp. 184-185.

[8] Vakoufaris, C., I. Spilanis and T. Kizos (2007) ‘Collective action in the Greek agrifood sector: evidence from the North Aegean region’, British Food Journal 109(10): 777-791, p. 789.

[9] Yannis Mandalas, CEO of Mediterra SA (the Mastiha cooperative’s subsidiary company), interview, Athens, 12.7.2018.

[10] Crouch, C. (2005) Capitalist Diversity and Change: Recombinant Governance and Institutional Entrepreneurs. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

[11] See also: Acemoglu, C. and M.O. Jackson (2015) ‘History, Expectations, and Leadership in the Evolution of Social Norms’, Review of Economic Studies 82(2): 423–56; Farrell, H. (2009) The Political Economy of Trust: Institutions, Interests, and Inter-Firm Cooperation in Italy and Germany. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 140-145.

[12] See also: Shane, S. (2000) ‘Prior Knowledge and the Discovery of Entrepreneurial Opportunities’, Organization Science 11(4): 448-469; Morrison, A. (2004) ‘“Gatekeepers of Knowledge” within Industrial Districts: Who they Are, How they Interact’, CESPRI Working Paper Series No. 163. Milan: Centro di Ricerca sui Processi di Innovazione e Internazionalizzazione, Bocconi University.

[13] See: Olson, M. (1965) The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

[14] Aristos Doxiadis, ‘Cooperation against the odds’ («Η συνεργασία σε αντίξοες συνθήκες»), Kathimerini, 1.1.2022, available at: https://www.kathimerini.gr/opinion/561651055/i-synergasia-se-antixoes-synthikes/

[15] Fritz Bläuel, founder of the firm “Mani Bläuel”, interview, Lefktro Messinias, 12.7.2017.

[16] Minutes of the Santo Wines General Assembly meetings, Act 117, Jul. and Aug. 1989.

[17] Yannis Boutaris, winemaker, interview, Chalkidiki, 8.8.2017.

[18] Yannis Mandalas, interview, 12.7.2018.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Dimitris Steinhauer, CEO of Concepts S.A., interview, Athens, 17.9.2018.

[21] Crouch, Capitalist Diversity and Change, p. 90.

[22] Markos Kafouros, President of the Santo Wines Cooperative and Vice-Mayor of Santorini, interview, Santorini, 15.4.2018.

[23] Spilanis, Y. (2017) ‘Αποτύπωση της κατάστασης της τουριστικής δραστηριότητας και των επιπτώσεών της στον προορισμό, ανάλυση SWOT και εναλλακτικά σενάρια πολιτικής’ [Depiction of the Situation of Touristic Activity and its Impacts on the Destination, SWOT Analysis and Alternative Scenarios for Policy], report. Mytilene: Tourism Observatory of Santorini, University of the Aegean, p. 21.

[24] Intervention by K. Zekkos in: Vatopoulos, N., N. Zorzos, Y. Spilanis, N. Schmitt and K. Zekkos (2018) ‘Πολιτιστική Διαδρομή Σαντορίνης’ [Cultural Trail of Santorini]. Panel discussion at the 5th Meeting of the members of the Diazoma association, Elefsina, Greece (21-22.4.2018). Accessed 5.9.2020 <https://www.blod.gr/lectures/politistiki-diadromi-santorinis/>.

[25] See also: Ostrom, E. (1990) Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[26] See also: Sabel, C. (1993) ‘Studied Trust: Building New Forms of Cooperation in a Volatile Economy’, Human Relations 46(9): 1133-70; McDermott, ‘The Politics of Institutional Renovation and Economic Upgrading’.

[27] See: Vandecandelaere, E., C. Teyssier, D. Barjolle, S. Fournier, O. Beucherie, and P. Jeanneaux (2020) ‘Strengthening Sustainable Food Systems through Geographical Indications: Evidence from 9 Worldwide Case Studies’, Journal of Sustainability Research, 2(4): e200031.

[28] European Parliament and Council of the European Union (2013) ‘Regulation (EU) No 1308/2013 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 December 2013 Establishing a Common Organisation of the Markets in Agricultural Products’. Accessed 5 September 2020 <https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32013R1308&from=EN>.

[29] Council of the European Union (1992) ‘Council Regulation (EEC) No 2081/92 of 14 July 1992 on the Protection of Geographical Indications and Designations of Origin for Agricultural Products and Foodstuffs’. Accessed 5.9.2020 < https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31992R2081&from=EN>.

[30] Markos Kafouros, interview, 15.4.2018.

[31] Agronomist employed by the Lemnos local authorities, interview, Lemnos, 2.9.2019.

[32] Representative of the Santo Wines Cooperative, interview, Santorini, 16.4.2018.

[33] Oenologist at a private Santorini winery, interview, Santorini, 17.4.2018.

[34] See also: Healy, R. (1994) ‘The “common pool” problem in tourism landscapes’, Annals of Tourism Research 21(3): 596-611; Brunori, G. and A. Rossi (2000) ‘Synergy and Coherence through Collective Action: Some Insights from Wine Routes in Tuscany’, Sociologia Ruralis 40(4): 409-423.

[35] Kostas Konstantinidis, hotel owner and conference tourism pioneer on Santorini, interview, London, 30.10.2019.

[36] Ibid.

[37] Giorgos Chatzigiannakis, founder of the Selene Restaurant on Santorini, interview, Santorini, 17.4.2018.

[38] Entrepreneur and President of a Rental Rooms Association, interview, Chalkidiki, 9.8.2017.

[39] Representatives of the “Geothira” municipal company, interview, Santorini, 18.4.2019.

[40] Grigoris Tasios, President of the Hotel Association and Tourism Organisation of Chalkidiki, interview, Chalkidiki, 11.8.2017.