- Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a game changer for Europe and the global system and a call for the EU to emerge as a coherent security actor.

- Any EU discussion about an autonomous EU military capacity becomes irrelevant in the face of a systemic global security challenge, such as Russia, which cannot be dealt with through the existing or envisaged EU military instruments.

- Faced with a security challenge on a global scale, NATO remains the only game in town.

- The EU ambition of developing its strategic autonomy becomes practically meaningful only within the transatlantic alliance.

- EU member-states should take advantage of the existing clauses that enable significant steps to be taken towards foreign and security integration.

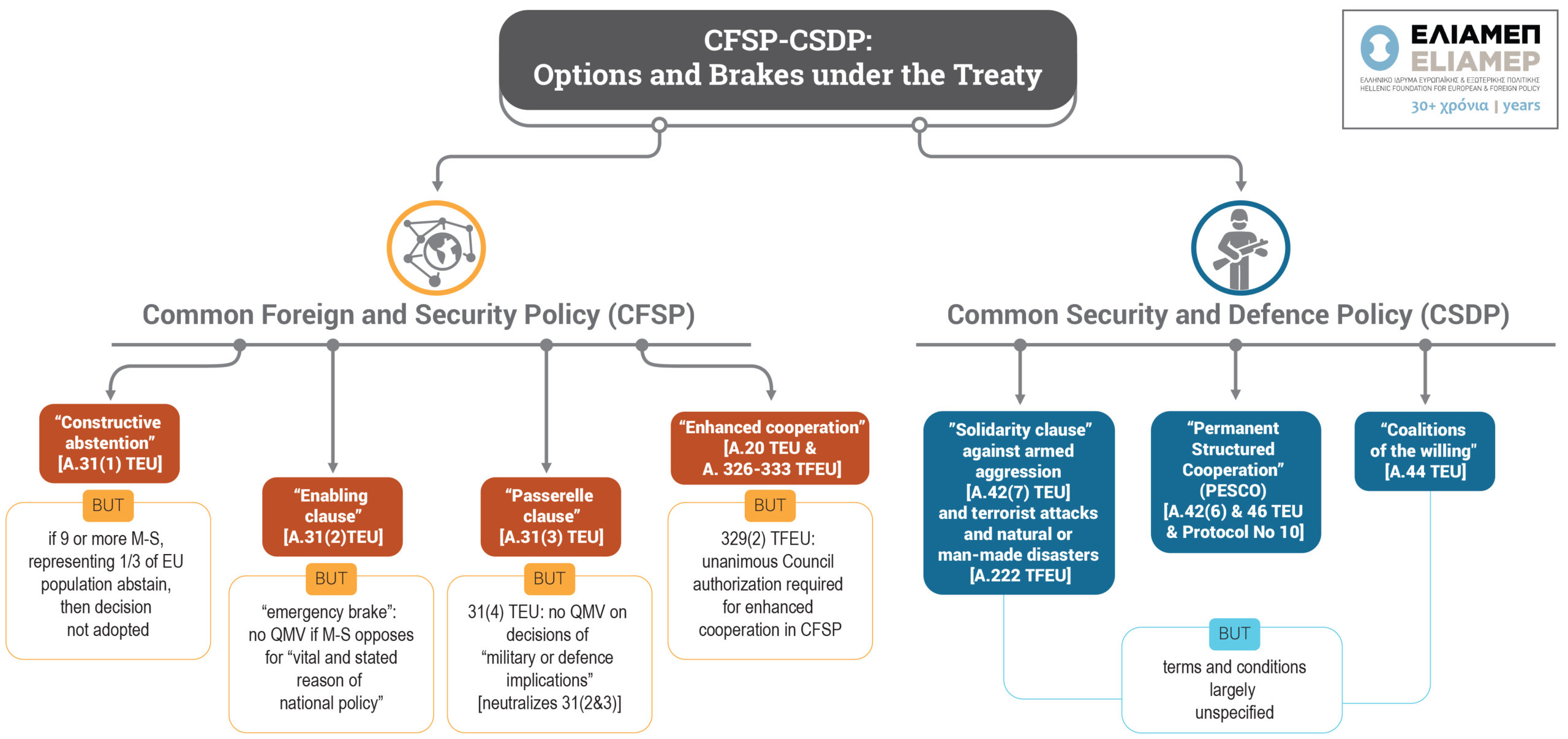

- The existing Treaty framework provides legal space for significant advances in the field of foreign and security integration, even though all relevant Treaty Articles contain strong ‘brakes’ which enable member-states to retain control of the process.

- Enhanced cooperation in EU foreign and security policy remains an important way forward, even though there are significant safety clauses.

- The ‘mutual defence’ or ‘mutual assistance’ clause (Article 42(7) of TEU) and the ‘solidarity clause’ (Article 222 of TFEU) are the closest things the EU has to security guarantees. Adding teeth to 42(7) should be an EU priority.

- Supporting EU ‘coalitions of the willing’ (Article 44 of TEU) also provides the opportunity for swifter military action under the EU aegis.

- The modality of cooperation between such coalitions and the EU rapid deployment capacity, which is also envisaged in the Strategic Compass and the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO), has still to be worked out.

- Transition to qualified majority voting (QMV) in EU foreign policy decision-making presents both advantages and disadvantages, both from the standpoint of the EU and of the dissenting member states.

- The EU cannot become a credible global power if it cannot reach collective decisions on EU foreign and security policy. Moving towards QMV would address structural weaknesses and serve the objective of European sovereignty.

- However, smaller member-states need a strong and explicit reassurance that they can always use the existing emergency brakes when they consider an issue which is to be decided on by QMV to be a matter of national security.

- Transition to QMV should be the result of the gradual forging of a common foreign policy understanding on the major security challenges facing the EU.

- Human rights issues and sanctions are a good place to start when building momentum towards QMV.

- In the meanwhile, the current reform effort should be focused on investing in the institutional framework of EU foreign and security policy and making good use of existing instruments.

Read here in pdf the Policy Paper by Spyros Blavoukos, Senior Research Fellow, Head, Ariane Condellis Programme; Associate Professor at the Athens University of Economics and Business and George Pagoulatos, Director General of ELIAMEP; Professor of European Politics and Economy at the Athens University of Economics and Business (AUEB).

(Photo: europarl.europa.eu)

Introduction

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is one of those turning points in history when the tectonic plates of the international system collide and tidal waves flush away many former systemic constants.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is one of those turning points in history when the tectonic plates of the international system collide and tidal waves flush away many former systemic constants. There is no doubt that the emphasis of the international community should first and foremost be on countering President Putin’s aggression and bringing the growing bloodshed to a swift end. At the same time, we cannot ignore the fundamental challenge of establishing a new stable European and global order to replace the one that has now been violently destroyed. In this light, might the time finally have come for the EU to emerge as a coherent security actor in Europe and beyond?

Crises generate opportunities for action. The EU partly overcame its tradition of hesitant and costly incrementalism in its response to the Covid-19 crisis, where it acted with unprecedented boldness by launching NextGenerationEU funded by common borrowing. What Covid-19 was for EU fiscal integration, Putin could become for EU security and defence integration. Rapidly bridging internal differences, the EU27 reacted in unity and in synch with Washington DC in imposing a menu of severe sanctions against the Putin regime and providing €450m worth of arms supplied to Ukraine. In a momentous shift, Germany abandoned a 70+year tradition of pacifism, announcing an additional €100bn defence budget. A lesson to be drawn is that when the political will is there, formal rigidities can be overcome. Due to its cataclysmic consequences, the Ukrainian crisis has triggered an exceptional degree of unity and coherence among European political leaders. This alone has been remarkable, given the multiple economic and energy dependencies of several EU member-states on Russia. The objective now is to take advantage of this window of opportunity and increase the EU’s assertiveness and effectiveness in defending its common interests and values, at least in its immediate neighbourhood. This is also the goal of the Strategic Compass currently under discussion, building on the (limited) progress being made in the field of defence cooperation.

Any EU discussion about an autonomous EU military capacity becomes irrelevant in the face of a systemic global security challenge.[…] Faced with a security challenge on a global scale, NATO remains the only game in town. The EU ambition of developing its strategic autonomy therefore becomes realistically meaningful only within the transatlantic alliance.

However, notwithstanding the EU’s united response, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has also allowed us to draw several important conclusions:

First, any EU discussion about an autonomous EU military capacity becomes irrelevant in the face of a systemic global security challenge. A security threat raised by a military and nuclear superpower such as Russia cannot be dealt with through the existing, or even the envisaged, EU military instruments (an EU rapid deployment capacity, various PESCO projects, EU battle groups). Such instruments are meant to be functional and effective within the framework of Petersberg tasks—countering security threats such as terrorism in Sahel, or undertaking a stabilisation mission in Africa—, but not providing defence reassurance for EU member-states.

Second, faced with a security challenge on a global scale, NATO remains the only game in town. The EU ambition of developing its strategic autonomy therefore becomes realistically meaningful only within the transatlantic alliance, especially given the uncontested priority attached to NATO by the Central and Eastern European member-states. European strategic autonomy in that sense addresses the possibility that European security priorities may at times diverge from those of its major transatlantic partner, given the direct security challenges emanating from Europe’s Southern and Eastern neighbourhood. In such cases, a division of labour within the NATO alliance, avoiding duplication and increasing transatlantic deterrence capacity, is both meaningful and constructive. This has been increasingly the case over the last decade, with the US shifting its priorities towards the Indo-Pacific.

EU member-states should take advantage of the existing clauses that enable significant steps to be taken towards foreign and security integration.

In this policy paper, we seek to identify the ways in which the EU can best improve the effectiveness of its common foreign and security policy within the existing institutional and legal framework. We pragmatically assume no Treaty change, since, though potentially desirable, no such change is considered likely in the foreseeable future. Given the urgency of establishing a new regional security order, EU member-states should take advantage of the existing clauses that enable significant steps to be taken towards foreign and security integration. Alongside them, bolder leaps should be also considered, including, for example, the extensive use of majoritarian decision-making rules in foreign policy. However, the discussion on qualified majority voting (QMV) should neither monopolize the evolving osmosis between member-states nor undermine the potential of the other relevant clauses of the Treaty. Otherwise, the dynamics of this critical juncture may soon evaporate.

An overview of the most relevant Treaty clauses

Does the existing Treaty framework provide legal space for significant advances in the field of foreign and security integration? The answer should be affirmative. In 2019, the European Parliamentary Research Service identified a few articles in the Lisbon Treaty that were dormant or had been under-exploited (Bassot, 2019). Seeking to unlock the reform potential of the EU Treaties, the study proceeded with an article-by-article analysis of possible breakthroughs in various policies and sectors, including foreign policy and defence cooperation. Subsequent studies and works have taken up the challenge of exploring further and in greater depth the potential for deepening integration in these two fields without Treaty revisions (Deen, Zandee and Stoetman, 2022; Scazzieri, 2022; Cameron, 2021; Lațici, 2021; Nováky, 2021; Koenig, 2020; Nadibaitze, 2020; Schuette, 2019). The following analysis reviews the more relevant articles and clauses, contributing to this important discussion.

Almost all the relevant Treaty Articles contain strong ‘brakes’ which enable member-states to retain control of the process.

A general observation that holds for almost all the relevant Treaty Articles is that they contain strong ‘brakes’ which enable member-states to retain control of the process. This is politically understandable and even collectively rational. Foreign policy, security and defence lie at the core of national sovereignty; therefore, any steps forward towards greater integration need to be closely scrutinised and capable of being halted at any time, if necessary, by the constituent member-states.

Article 31, TEU: Introducing decision-making flexibility into the CFSP

The main aim of Article 20 of TEU is to increase flexibility in the modus operandi of the CFSP, always under the continuous oversight of member-states.

The starting point of any discussion is Article 31 of Title V of the Treaty on European Union (TEU) that deals with the general provisions on the Union’s external action as well as the specific provisions on the common foreign and security policy of the EU. The main aim of this Article is to increase flexibility in the modus operandi of the CFSP, always under the continuous oversight of member-states.

More specifically, the second sub-paragraph of the first clause introduces and endorses the notion of ‘constructive abstention’ (A.31(1)). Accordingly, a member-state with a diverging point of view on an issue can make a formal declaration to this effect that would allow it to abstain from a unanimous vote as well as relieving it of the obligation to apply the respective decision. This allows the other member-states to continue with the decision, which commits the EU. A practical example is the European Union’s 2008 decision to set up a civilian CSDP mission in Kosovo, in relation to which Cyprus invoked its constructive abstention. If, however, nine or more states, representing one third of the EU population, abstain, then the decision is not adopted.

In the same Article, the second clause empowers the Council to decide and act by QMV in several exceptional cases (Article 31(2)). This ‘enabling clause’ applies explicitly when defining an EU position on the basis of a European Council decision related to the EU’s strategic interest and objectives; when defining an EU position based on a proposal from the HR/VP, as requested by the European Council on the initiative of the latter or of the HR/VP; when implementing decisions already taken defining a Union action or position; and when appointing special representatives. Once again, an ‘emergency brake’ exists: if a member of the Council opposes a particular decision for a ‘vital and stated reason of national policy’, no vote is taken. Failure to find a compromise solution in the Council means that the issue is referred to the European Council for a decision by unanimity.

The third clause empowers the European Council to unanimously adopt a decision stipulating that the Council shall act by a qualified majority in cases over and above the four identified in 31(2) above (Article 31(3)). In practice, this ‘passerelle clause’ of the CFSP provides ample scope for a bold extension of majoritarian decision-making in the Council on foreign policy issues. However, it does not give carte blanche to Heads of State and Government. In the fourth clause of the same Article, it is explicitly mentioned that neither the ‘enabling clause’ nor the ‘passerelle clause’ are applicable to decisions which have military or defence implications (Article 31(4)). This substantially curtails the potential of this Article to drive enhanced security integration, effectively neutralizing the dynamics of 31(2&3).

Article 20, TEU: Enhanced cooperation in EU foreign and security policy

The second Treaty article with significant unexploited potential is Article 20 of Title IV of the Treaty on European Union (TEU), which includes the provisions on ‘enhanced cooperation’. Enhanced cooperation is considered the last resort when agreement to move forward on a topic linked to the non-exclusive competences of the Union is not feasible. Such cooperation is open to all member-states that may wish to join the initiative at a later stage. The enhanced cooperation framework could therefore be used to overcome resistance from member-states that are negatively disposed towards closer and deeper foreign and security policy cooperation.

However, once again, there are significant safety clauses that curtail the potential of this provision. To begin with, a minimum of nine member-states are required. More importantly, enhanced cooperation is only applicable in the field of common foreign and security policy under very strict conditions, as stipulated in Article 329 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Article 329(1&2) TFEU). To be more specific, authorisation to proceed with enhanced cooperation in this specific field requires a unanimous Council decision. In addition to that limitation, as in Article 31 TEU discussed above, the provisions stipulating that the Council has the capacity to decide unanimously that it will act by qualified majority voting (QMV) are not applicable to decisions which have military or defence implications (Article 333(3) TFEU). Although the exact scope and ratio legis of this clause may be open to discussion and interpretation, in practice, the Treaty leaves no scope for moving towards closer defence cooperation along this path, either.

Articles 42(6) & 46, TEU (and Protocol No 10): The potential of the Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO)

Contradicting the provisions of Article 20 of TEU and Article 333(3) of TFEU, the concept of enhanced cooperation is extended to the EU’s common security and defence policy through Articles 42 and 46 of Section 2 of the TEU. According to the former, member states whose military capabilities fulfil higher criteria, and which have made more binding commitments to one another in this area, may establish permanent structured cooperation within the Union framework (Article 42(6)). This security cooperation framework was neglected after it was activated in December 2017, but has been gaining momentum recently. The PESCO framework introduces a structured process for gradually deepening defence cooperation with a view to delivering the capabilities required to undertake the most demanding missions. Given the deep ties between defence and national sovereignty, PESCO has been invaluable in promoting military cooperation, which would otherwise have remained vulnerable to the heterogeneity of national preferences (Blockmans and Crosson, 2021). Its added value lies in the list of ambitious and binding commitments jointly undertaken by participating member states and outlined in Protocol No 10. PESCO constitutes the backbone of present and future military cooperation. By investing heavily in interoperability and training, and already into its fourth wave, PESCO aims to enhance European military capacities through its approved projects and hence provide an operational fertile ground for defence integration once political conditions allow it (Crosson, 2021).

Article 42(7), TEU and Article 222, TFEU: Providing security guarantees

Article 42(7) of TEU and Article 222 of TFEU are the closest things the EU has to security guarantees.

Article 42(7) of TEU and Article 222 of TFEU are the closest things the EU has to security guarantees. Unlike NATO, the EU has not been built to provide the collective public good of security. However, the gradual emergence of the EU as a security actor over the last three decades has led to the incremental build-up of a security acquis, which is encapsulated in these two articles. They introduce the concept of security solidarity into the EU legal framework in two distinct ways: Article 42(7) of TEU, also dubbed the ‘mutual defence’ or ‘mutual assistance’ clause, introduces security solidarity in a more general way: armed aggression against one member-state generates an obligation for the other EU member-states to provide aid and assistance to the best of their means, in accordance with Article 51 of the United Nations Charter. However, although it may resemble NATO’s collective defence clause, Article 42(7) has deliberately been drafted to be more restrictive in terms of its territorial scope. This generates concerns about its applicability in the maritime domain, cyberspace or space itself, curtailing its relevance vis-à-vis modern security threats and challenges. The article remained dormant until France invoked it in 2015 in response to the Bataclan attacks. Greece also hinted at its invocation in 2020, in response to its heated summer confrontation with Turkey. In the discussions surrounding the EU Strategic Compass, several member-states have called for the clause to be operationalised and more clearly demarcated (Deen, Zandee and Stoetman, 2022). During the informal European Council at Versailles on 10–11 March 2022, Finland and Sweden referred in a joint letter to the need to clarify the procedure to be followed in the event of the clause being activated again. The gap between NATO and non-NATO EU members increases the significance of Article 42(7) still further. Adding teeth to this provision should be an EU priority.

The gap between NATO and non-NATO EU members increases the significance of Article 42(7) still further. Adding teeth to this provision should be an EU priority.

Article 222 of TFEU, more commonly identified as the ‘solidarity clause’, is more specific in nature, referring to terrorist attacks and natural or human-made disasters. Nonetheless, interest in it has fluctuated over time. Some of the objectives–indeed, even the rationale–of its provisions have been overtaken by concrete initiatives and decisions, for example in the area of terrorism prevention, with significant advances having reduced the urgency of its implementation (Myrdal and Rhinard, 2012; Keller-Noellet, 2011). However, the article regained its relevance when it was explicitly invoked in 2014 in the EU’s cyber security strategy, and later on vis-à-vis hybrid threats. It gained further impetus in the aftermath of the 2014–15 terrorist attacks in France, Belgium, and elsewhere (Blockmans, 2014).

Together, the combined provisions of 42(7) TEU and 222 TFEU could amount to the emergence of a European collective security and defence architecture. This architecture is cross-national in nature, being based on the individual military capabilities of member-states and the obligation to use them in the defence of another member-state. However, read in conjunction with the mid- to long-term horizon of the PESCO projects, 42(7) TEU and 222 TFEU are binding EU member-states together in the progressive framing of a common defence.

Article 44, TEU: Supporting EU ‘coalitions of the willing’

Appropriately implemented, Article 44 provides the opportunity for swifter military action under the EU aegis. Such action is mutually beneficial, profiting both the EU and the participating member-states.

The EU military operational capacity required to give flesh and bones to the common security and defence policy does not necessarily require the participation of every member-state. According to Article 44: “The Council may entrust the implementation of a task to a group of member states which are willing and have the necessary capability for such a task”. This provision paves the way for the emergence of ‘coalitions of the willing’ ready and eager to undertake a particular task from the expanded list of Petersberg tasks which include disarmament operations and humanitarian and rescue tasks, as well as crisis management tasks undertaken by combat forces, including peace-making and post-conflict stabilisation. It brings ad hoc groupings of member-states within the EU Treaty framework, where they may become otherwise active and operational outside the EU, institutionalising and legitimizing them. Unanimity requirements for the launching of military action have hampered CSDP missions in Libya, Mali and Iraq against Islamic State, and during the evacuation of Afghanistan more recently. Having failed to act and launch an EU mission, member-states have often moved forward in small groups, as they did in the European Maritime Awareness Mission in the Strait of Hormuz (EMASOH) in 2019.

Appropriately implemented, Article 44 provides the opportunity for swifter military action under the EU aegis. Such action is mutually beneficial, profiting both the EU and the participating member-states. From the EU point of view, it flies the EU flag abroad and enables military mobilisation to be linked with other, civilian, EU missions in the field, allowing for a holistic and integrated engagement. An Article 44 mission will most probably be ready for launch far faster than a proper CSDP mission and will benefit from more operational flexibility. For participating member-states, the EU engagement bestows legitimacy on the mission, helping counter accusations of imperialistic and/or colonialist motives. Furthermore, the EU will cover part of the costs of the mission, making it more affordable for participating member-states. Finally, it will enable member-states with constitutional constraints, such as Germany, to participate in such missions (Scazzieri, 2022).

The modality of cooperation between such coalitions and the EU rapid deployment capacity has still to be worked out.

The idea of supporting EU ‘coalitions of the willing’ was advocated by Germany’s former defence minister, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer, in the aftermath of the evacuation of Kabul in September 2021. It was backed by several member-states, and eventually found its way into the draft Strategic Compass, which calls for more flexible modalities in the implementation of Article 44. The modality of cooperation between such coalitions and the EU rapid deployment capacity, which is also envisaged in the Strategic Compass, has still to be worked out.

Unpacking QMV in EU foreign policy decision-making

Unanimity dominates decision-making in CFSP; however, the pressure is mounting to move to a more majoritarian rule, with many voices considering this a prerequisite for any meaningful and substantial upgrade of the EU’s global role. In his 2018 State of the Union address to the European Parliament, European Commission President Jean Claude Juncker called for qualified majority decisions in foreign policy to improve the EU’s efficiency and effectiveness in world affairs. This ambitious appeal was operationalised by the Commission, which introduced proposals to the European Council for the use of QMV in decisions relating to the imposing of sanctions, the launching of EU civilian missions, and when dealing with human rights issues. These proposals were based on the ‘passerelle clause’ and received the full backing of the European Parliament. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen also indicated her support for and embracing of this prospect in her political guidelines for her period in office, mandating the High Representative to work towards this decision. However, she did not include civilian missions among the areas in which QMV could be applied, departing from Juncker in this regard.[1]

For their part, in the 2018 Meseberg Declaration, key member-states including France and Germany expressed their readiness to discuss and explore the potential of using QMV in foreign policy-making “… in the framework of a broader debate on majority voting regarding EU policies”.[2] In practice, this wording reflects France’s intention to link QMV in foreign policy to tax policy issues (Koenig, 2020), but it is still quite a significant change compared to the traditionally intergovernmentalist French views vis-à-vis the rules governing CFSP. Germany has repeatedly affirmed its intention to move away from unanimity. Several other countries, including Belgium, Finland, Spain and the Netherlands, have also publicly supported a move in this direction, being especially vocal in the wake of vetoes exercised by stand-alone member-states that have frustrated the rest of the group. For example, Greece vetoed an EU statement on China’s human rights record in 2017; in 2019, Italy blocked an EU common position on Venezuela declaring Maduro’s reelection illegitimate and recognizing Guaido; Cyprus blocked sanctions against Belarus in 2020, linking them to similar sanctions against Turkey; and Hungary twice blocked statements against China and Israel, respectively, in 2021. Spain and the Netherlands took up this issue in their March 2021 non-paper, their contribution to the ongoing discussion on the Strategic Compass of the EU. Their claim is that QMV will reinforce the much-sought strategic autonomy of the EU (Nováky, 2021). Still, many member-states (Koenig, 2020, estimates them at ten), especially from the Southern and Eastern flank of the EU and mostly small- and medium-sized countries, are supposed to be either hesitant or openly against a shift away from unanimity. They have also mobilised to successfully block relevant developments, as they did, for example, in 2020 when the Foreign Affairs Council rejected Borrell’s proposal that the Council act with QMV on issues related to the implementation of the new Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy (Nováky, 2021).

We present and discuss the main arguments both for retaining and abolishing unanimity in foreign policy.

Bearing this background in mind, we present and discuss the main arguments both for retaining and abolishing unanimity in foreign policy. For each case, we cluster the arguments into two categories: first, for the EU as a whole and second, for the member-state(s) opposed to the introduction of QMV.

QMV will increase the effectiveness and responsiveness of the EU by freeing it from the constraints of the lowest common denominator.

From the point of view of the EU as a whole, QMV can be beneficial for four reasons:

- QMV will increase the effectiveness and responsiveness of the EU by freeing it from the constraints of the lowest common denominator. As a result, the EU will be able to respond more rapidly and in a more appropriate way to security crises, thus avoiding the trap of international irrelevance.

- The shift to QMV will also discourage EU member-states from forming other extra-EU groupings and formats of intervention. When frustrated EU member-states face recurring recalcitrance by holdout members, they may turn to such groupings to avoid paralysis. Such groupings are not new to the European foreign policy system: recently, there have been the E3 engagement in the Iranian crisis prior to the involvement of the High Representative (HR), for example, or the Normandy contact group in the first round of the Ukrainian crisis. The emergence of ad hoc groups undermines the unity, legitimacy and cohesion of the Union as a whole and its claims to have a common foreign policy.

- QMV will also help to counter ‘Trojan horses’, i.e. EU member-states with special links to and dependencies on third countries, like Russia, China or the United States. Due to these links, which may be economic in nature or based on cultural affinity, EU member-states are hooked up to the foreign policy priorities of the third countries, and act as their port paroles and agents within the EU. Taking advantage of the decision-making bottlenecks caused by unanimity, they can undermine the EU’s engagement with, and response to, a crisis.

- QMV will incentivise unity and put pressure on member-state(s) to endorse a common decision, despite any minor points of disagreement they may have on particular aspects. Acknowledging the possibility of being outvoted and marginalised, EU member-states with non-major reservations will think twice before voting against and blocking a policy proposal or action. This will allow the EU to gradually expand the scope of its common foreign policy positions, for example on human rights and sanctions.

The move away from unanimity would have some positives for the opposing member-state(s), too:

- Member-states–usually smaller ones–that often find themselves under pressure from powerful third countries to promote their interests in the EU (the ‘trojan horses’ mentioned above) can escape this predicament. Caught between the Scylla of often unbearable pressure from their European counterparts and the Charybdis of having to satisfy their external patron, these states will be relieved to be outvoted. Although being able to ‘have their cake and eat it’ may incentivise less responsible and free-rider attitudes, it could take pressure off such member-states to detonate their veto bomb.

- In the same vein, the governments of EU member-states that are under political pressure domestically to adopt a militant and obstructive position, but may not necessarily think this is the best way forward, will be able to instrumentalise QMV in order to remain in the EU minority for domestic political purposes, while not hindering the collective decision and EU action in a field. Again, ‘free riding’ attitudes may arise but, overall, QMV will lead to collective utility maximization.

The arguments in support of retaining the current system of unanimity in EU foreign policy are also convincing. From the point of view of the opposing member-state(s):

- First and foremost, unanimity offers then more chances to represent and safeguard their national interests. Smaller member-states in particular, or countries with specific national preferences, are afraid—reasonably–that their sensitivities will be disregarded and their concerns overlooked in the name of the common EU foreign policy. The existing consensus norm does not constitute a credible guarantee, since it relies on the implicit threat of a veto hovering over all discussions and deliberations on foreign policy issues. As we have illustrated in the first section, every step towards circumventing the unanimity principle in the Treaties comes accompanied by a safety valve to entertain the concerns of the fiercest opponents of QMV in foreign policy.

- Domestically, sticking to unanimity may be convenient politically for two main reasons:

- The use of the veto conveys and projects an image of a strong government willing and ready to defend its country’s perceived interests. Domestic and EU politics are fully intertwined, and domestic political games nest within European ones. In these two-level games, a veto can be invoked for domestic purposes only at the expense of the common EU foreign policy. Although this choice may lead to sub-optimal collective decisions for the EU, it may be extremely useful and beneficial for—short-sighted–national leaders and policy makers.

- The use of QMV in the Council may lead to domestic political crises. Besides the instrumental and political calculus-based reasoning of the previous paragraph, the negative repercussions of the use of QMV cannot be dismissed outright. If it is often outvoted, a national government may face a significant backlash against both itself and the EU, which may result in domestic political upheaval.

From the EU’s point of view, QMV in foreign policy may also be unwanted for three main reasons:

- Resorting to QMV has a potentially negative effect on the legitimacy and unity of the EU and the decisions it takes. To start with, if member-states are often outvoted, the EU’s decisions may be de-legitimized, since the EU will no longer appear to be a Union of 27 but a Union of the powerful plus some marginalised member-states. A corollary concern is the way in which member-states that are systematically outvoted over major issue(s) will react. Their alienation may lead to intra-EU destabilisation, with such states expressing their discontent in other policy areas in a kind of negative spillover effect. In extremis, such a condition may raise doubts about the country’s participation in the process. Crudely put, can the EU afford another ‘Brexit’? Additionally, the requirement of unanimity forces member-states to insist on negotiations in pursuit of common ground, even if this results in the lowest common denominator. In the words of European Council President Charles Michel in September 2020: “…while the unanimity requirement slows down and sometimes even prevents a decision, it also forces member-states to engage with each other to find a common position”.[3]

- Reaching decisions by QMV may have practical implications and lead to problematic implementation. Following on straight from the first point, we should bear in mind that a member-state that repeatedly disagrees and is marginalised may find it difficult to comply with the requirements of a decision, and either intentionally or unintentionally ignore and obstruct its implementation.

- Finally, it is worth considering whether the use of QMV will increase decision-making effectiveness, after all. There is no denying that individual rigidities will most probably be overcome, which is one of the strongest arguments put forward by the proponents of QMV. However, EU politics, in foreign policy issues as in all other policy areas, usually evolves around groupings of states which form relatively coherent and stable clusters. The existence of groups like the Visegrad 4, the Frugal Four and others suggests that the potential for a ‘blocking minority’ in foreign policy is very high, resulting in an even more complex negotiation process. In other words, QMV may be appropriate and help bypass individual hardliners and outliers, but it will not simplify most of the foreign policy dynamics of the Union by much.

The Way Forward

The EU cannot become a credible global power if it cannot reach collective decisions on foreign and security policy.

The EU cannot become a credible global power if it cannot reach collective decisions on EU foreign and security policy. If the EU is held hostage by individual veto-waving member-states in every important foreign policy decision, Europe will be incapable of defending its interests and values and unable to provide sufficient security guarantees to its members. The EU is often regarded by allies and foes alike as indecisive and weak, because of its inability to rise beyond lower common denominator decisions. Moving towards QMV would address this structural weakness and serve the objective of European sovereignty.

Moving towards QMV would address this structural weakness and serve the objective of European sovereignty.

However, there are two basic prerequisites that would need to be in place before QMV became the norm in foreign and security policy-making:

- First, smaller member-states need a strong and explicit reassurance that they can always use the existing emergency brakes when they consider an issue which is to be decided on by QMV to be a matter of national security. Although this safeguard is already Treaty-enshrined, a political statement by the European Council would signal that the EU unequivocally embraces the consensus principle in foreign policy-making when a justified national preoccupation is invoked. After all, solidarity is not only about mobilising and assisting a European partner in need; it is also about respecting a partner’s core national sensitivities.

- Second, and more importantly, transition to QMV should be the result of the gradual forging of a common foreign policy understanding on the major security challenges facing the EU. On the path to economic and monetary integration, the convergence of economic cycles was rightfully deemed to be an important precondition for the smooth functioning of EMU. Similarly, in the case of foreign, security and defence integration, the convergence of ‘security cycles’ should also be prioritized, in the sense of building up a common approach and shared prioritization of the major security threats facing the EU and the best ways of addressing them. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine has shown that a common EU position is not utopic, even in such policy area as contested as Ukraine, over which the EU has been deeply divided. Seemingly long-term projects may indeed come rapidly to fruition when history is accelerated.

In the meanwhile, immediate action should be guided by ambitious pragmatism. The primary emphasis of the current reform effort should be on the implementation of EU foreign policy and the use of the existing instruments and tools, rather than on the potentially divisive mode of majoritarian decision-making. The latter can be tested in narrow fields that feature genuine, rather than generated, intra-EU cohesion and in which the overwhelming majority of member-states are on the same side of the fence. Even if human rights and associated sanctions occasionally stir up some controversy between member-states, they still constitute a field of action in which member-states are (or should be) motivated by the same core set of liberal principles and values. Exceptions notwithstanding (the word Orbán comes to mind), human rights and associated sanctions are two straightforward themes with no permanent outliers that could be consistently and continuously outvoted in a possible systematic use of QMV. This is the reason why they were put forward by the Commission in the first place, in its 2018 proposal. In a pattern revealing of the neo-functionalist dynamics that have driven closer integration over the decades, the build-up of cooperation will create the avalanche effect that will sweep away national reservations over the course of time. More ambitiously, we need to further reflect on other issue areas that can be used as QMV testbeds, especially in the shadow of the horrific war in Ukraine.

The build-up of cooperation will create the avalanche effect that will sweep away national reservations over the course of time.

Finally, it is important to invest more in the institutional framework of EU foreign and security policy. The agenda of the French Presidency includes the allocation of more powers to the High Representative, especially in times of crisis. Spread thin in such periods, the HR and the European External Action Service (EEAS) either need more resources or to use the existing resources in a smarter way. The delegation of tasks to an individual member-state or group of member-states on the basis of experience, willingness and expertise is a good way to enable the HR to focus on the strategic dimension of their mandate. The reinforced coordination of the relevant Directorates General of the Commission is also imperative, and the same applies for the different geographical desks in the EEAS and the Service’s security-related personnel (Cameron, 2021). In EEAS, more emphasis should be placed during the recruitment process on economic diplomacy, which is tightly bound up with the EU’s international presence. This was an issue taken up by the Commission in its 2017 Reflection Paper on Harnessing Globalisation (European Commission, 2017). Currently, the EEAS is in charge of coordinating EU economic diplomacy in close cooperation with the Secretariat General of the European Commission and the active involvement of relevant Commission services. However, economic diplomacy needs to be more systematically integrated into both the EU strategic documents and high-level political dialogues with key third states and actors (Pangratis, 2019).

It is important to invest more in the institutional framework of EU foreign and security policy.

In conclusion, the Treaties do indeed open several paths towards closer integration in foreign, security and defence policy, each of which comes with an adjacent brake. This is unsurprising, given that such policies are situated at the perennial core of national state sovereignty. Introducing motion into such craftily balanced structures requires both catalytic events and transformative leadership. Putin has provided for the first. We have yet to see the second.

References

Bassot, E. (2019) ‘Unlocking the potential of the EU Treaties: An article-by-article analysis of the scope for action’, Study, European Parliament, European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS).

Blockmans, S. and Crosson, D. M. (2021) ‘PESCO: A Force for Positive Integration in EU Defence’, European Foreign Affairs Review, Special Issue, Vol. 26: 87–110.

Blockmans, S. (2014) ‘L’Union fait la force: Making the most of the Solidarity Clause (Art. 222 TFEU)’, in Govaere, I. and Poli, S. (eds), EU Management of Global Emergencies: Legal Framework for Combating Threats and Crises. Leiden: Brill, pp. 111–35.

Cameron, F. (2021) ‘Give Lisbon a chance: How to improve EU foreign policy’, Policy Brief, EPC.

European Commission (2017), “Reflection Paper on Harnessing Globalisation”, COM (2017) 240, 10 May, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM:2017:240:FIN

Crosson, D. M. (2021) ‘EU Defence Projects: Balancing Member States, money and management’, CEPS Policy Brief, No. 2021–02, December 2021.

Deen, R., Zandee, D. and Stoetman, A. (2022) ‘Uncharted and uncomfortable in European defence—The EU’s mutual assistance clause of Artcile 42(7)’, Clingendael report, January 2022.

Keller-Noëllet, J. (2011) ‘The Solidarity Clause of the Lisbon Treaty’, in E. Fabry (ed.), Think Global—Act European: The Contribution of 16 European Think Tanks to the Polish, Danish and Cypriot Trio Presidency of the European Union, June 2011, pp. 328–333.

Koenig, N. (2020) “Qualified Majority Voting in EU Foreign Policy: Mapping Preferences”, Hertie School, Jacques Delors Centre, Policy Brief, February.

Lațici, T. (2021) ‘Qualified majority voting in foreign and security policy: Pros and Cons’, Briefing, European Parliament, European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS).

Myrdal, S. and Rhinard, M. (2012) ‘The European Union’s Solidarity Clause: Empty Letter or Effective Tool? An Analysis of Article 222 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union’, UI Occasional Papers 2, 2012.

Nadibaidze, A. (2020) ‘Will the EU move to Qualified Majority Voting in Foreign Policy?’, Commentary, Vocal Europe, October 2020.

Nováky, N. (2021) ‘Qualified Majority Voting in EU Foreign Policy: Make It So’, Wilfried Martins Center for European Studies.

Pangratis, A. (2019) ‘EU economic diplomacy: Enhancing the impact and coherence of the EUs external actions in the economic sphere’, in Bilal and B. Hoekman (eds) Perspectives on the Soft Power of EU Trade Policy, London: CEPR Press, pp. 55–60.

Scazzieri, L. (2022) ‘Could EU-endorsed ‘coalitions of the willing’ strengthen EU security policy?’, Centre for European Reform (CER), Insight, 9 February.

Schuette, L (2019) ‘Should the EU make foreign policy decisions by majority voting?’, Centre for European Reform (CER), May 2019.

[1] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/legislative-train/theme-europe-as-a-stronger-global-actor/file-more-efficient-decision-making-in-cfsp

[2] https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/germany/events/article/europe-franco-german-declaration-19-06-18

[3] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/09/28/l-autonomie-strategique-europeenne-est-l-objectif-de-notre-generation-discours-du-president-charles-michel-au-groupe-de-reflexion-bruegel/