While the EU accession negotiations with Turkey are frozen, the economic and trade relations between the two – built mainly upon the Customs Union (CU) – remain vibrant. Nevertheless, the CU has been increasingly considered inadequate by various politicians and experts on both sides due to the rapidly changing economic and trade international environment. By and large, it is accepted that an upgraded/modernised CU can benefit the EU in political and regulatory terms, while Turkey can improve its welfare and its standing to international trade negotiations and competition. Greece, in turn, can also benefit economically from an upgraded/modernised CU in various sectors directly or indirectly, including agriculture, public procurement, FDI and tourism. However, there seems to be a widespread lack of willingness on the part of Greek politicians to consider giving the green light for negotiations between the European Commission and Turkey as well on the part of Greek bureaucrats, business elites and analysts pushing for a positive economic agenda with Turkey. The main reason is that security concerns override economic calculations. This is due to the fact that any investment of political capital by Greek politicians on this endeavour translates into instant losses in their public image due to Turkey’s aggressive behaviour towards Greece at the moment, while economic benefits deriving from an upgraded/modernised CU are only potential and long-term. Hence, Greek-Turkish relations are in a Catch-22 situation in that matter at hand. Greece will not support the opening of negotiations for the modernisation, while Turkey keeps threatening it, and Turkey will not abdicate from its aggressive and maximalist positions, while it feels alienated by the EU in global trade developments. Although security and political concerns in Greece override any discussions over economic relations with Turkey the governing party along with the parties of the major and the minor opposition appear receptive to sound out the possibility of an upgraded Customs Union provided that certain political conditions will be also attached to it, namely the incorporation of certain issues of particular importance to Greece, most notably related to security, defence, and migration.

You may find the Policy Paper, by Prof. Panayotis Tsakonas, Senior Research Fellow of ELIAMEP, Head of the Security Programme, and Dr. Athanasios Manis, ELIAMEP Research Fellow, here.

This Policy Paper was funded by the Centre for Applied Turkey Studies (CATS) of the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik/SWP).

A General Assessment of the Impact of the Customs Union

History and context of the Customs Union

By and large, the economic and trade relations between the EU and Turkey have been defined for more than twenty years by the Bilateral Preferential Trade Framework (BPTF) (BKP Development Research and Consulting, Panteia, & AESA, 2016: 10). The framework consists of the Customs Union, which entered into force on 31 December 1995, and companion agreements on coal and steel (CSA, which entered into force in 1996), as well as a preferential regime for trade in agricultural goods and fishery products (AFTR, which entered into force in 1998) (Ibid.).

The BPTF emerged as part of the 1963 Association Agreement (Ankara Agreement) that aimed to continuously strengthen trade and economic relations through “the progressive establishment of a Customs Union (CU) in three states: preparatory, transitional, and final, with protocols laying down the rules of the preparatory stage” (Berulava, Manoli, & Selcuki, 2019: 3). The 1970 Additional Protocol stipulated the rules for implementing the transitional stage for establishing the Customs Union that among others included the progressive abolition of customs duties between the European Economic Community (EEC) and Turkey over a period of twenty-two years (Ibid.).

The Customs Union that was agreed in 1995 has been characterised as the European “Convergence Machine” (Berulava et al., 2019: 1). The terms of the CU were specified in the Additional Protocol (For more information see Berulava et al., 2019: 3; BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 19-20). Specifically, Turkey would adopt the EU’s common external tariff (CET) for most industrial products as well as for the industrial components of agricultural products, and both the EU and Turkey agreed to eliminate all customs duties, quantitative restrictions and charges with equivalent effect on their bilateral trade (World Bank, 2014: i). Additionally, Turkey’s commercial and competition policies would have to be harmonised with those of the EU.

The CU does not cover primary agricultural products, iron and steel commodities of the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), services, and public procurement (Berulava et al., 2019: 3; World Bank, 2014: 57). However, both parties committed to gradually include agricultural products through ongoing negotiations aiming at establishing a free trade area (FTA)[1] and have been pushing towards expanding the CU into services and public procurement (Mertzanis, 2017: 3).

What is the impact on the European Union and Turkey?

In terms of the impact that the Customs Union has had on EU-Turkey economic relations and their respective economies, the outcome has been positive for both, especially for Turkey. Specifically, in its latest report on the matter, the World Bank argues that (World Bank, 2014: 19):

“The CU has been a catalyst for Turkey’s integration both with the EU and the world. In general, the CU has helped Turkey’s manufacturing sector through introducing increased competition as it has harmonized and decreased Turkey’s import tariffs for most industrial products from third countries to exactly the same levels as those faced by EU producers and opened Turkey to duty-free imports of these goods from world-class European firms. Crucially, it has also greatly strengthened the alignment of Turkey’s technical legislation and its quality infrastructure with that of the EU, streamlined customs procedures and eliminated the need for ROOs [rules of origin] on its trade with the EU. As suggested in the previous section this has likely been instrumental in helping Turkish producers integrate into global value chains, catalyzed FDI from the EU, and thus promoted the quality upgrading of Turkey’s exports.”

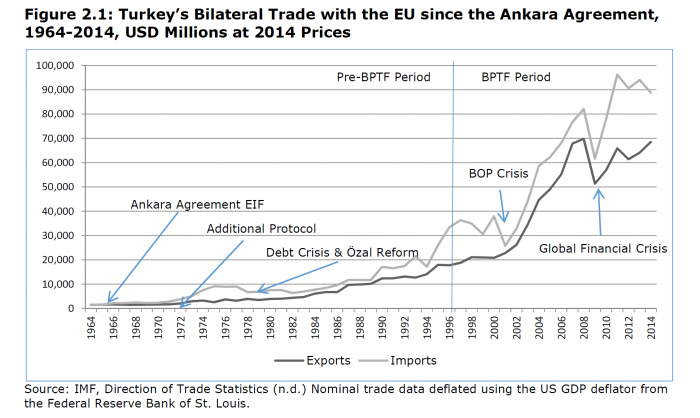

According to the European Commission’s report that was prepared as an impact assessment of the BPTF, including the Customs Union, and a study of future scenarios, Turkey’s trade with the EU increased exponentially in the BPTF period, namely after 1996, compared to the pre-BPTF period at 2014 USD prices (see Figure 1). Specifically, it was found that bilateral trade between Turkey and the EU quadrupled during the BPTF period (Ibid.: 27-28). Notably, Turkey’s economic reforms in the aftermath of the balance of payment crisis in 2001 boosted bilateral trade with the EU until the global financial crisis of 2008-2009 that momentarily stopped the upward trend.[2] The share of EU exports to Turkey rose from 3% – at the beginning of the BPTF period – to 5% in recent years, while the share of EU imports from Turkey rose from 2% to 3% (Ibid.: 10).

Figure 1

Turkey’s Bilateral Trade with the EU since the Ankara Agreement, 1964-2014, USD Millions at 2014 Prices

Source: BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 27

“….the BPTF did not translate into greater EU share of Turkey’s imports and exports […] it was observed that the total EU share remained the same during the BPTF period and even started to drop gradually after 2008, while increasing for the rest of the world.”

At the same time, the report highlighted the fact that the implementation of the BPTF did not translate into greater EU share of Turkey’s imports and exports (BKP Development Research and Consulting, Panteia, & AESA, 2016: 10, 28). On the contrary, it was observed that the total EU share remained the same during the BPTF period and even started to drop gradually after 2008, while increasing for the rest of the world. The report argued that “while the EU shared in this growth, the erosion of EU preferential access to the Turkish market by Turkey’s unilateral liberalization to the rest of the world pursuant to the Additional Protocol reforms, which was intensified by the general lowering of tariffs under the WTO agreement, is clearly visible in the steep decline of the EU’s share of Turkey’s imports during the 2000s” (Ibid.: 28). To illustrate this, while Turkey’s imports from the EU15 increased by 242% over the BPTF period, imports from the rest of the world increased by 470% (Ibid.).

“Bilateral trade in goods that were covered by the BPTF grew far more strongly than goods not covered by the BPTF”

However, the study found that “the positive effect of the BPTF is most clearly seen when comparing the performance of goods subject to the BPTF (CU, CSA, and AFTR) and those not subject to the BPTF. Bilateral trade in goods that were covered by the BPTF grew far more strongly than goods not covered by the BPTF” (Ibid.: 10). Furthermore, the EU has become the largest investor in Turkey over the years, accounting for three-quarters of total foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows (66,3% on average between 2008 and 2016) (Berulava et al., 2019: 4; World Bank, 2014: 1). As a result, European FDI has been the main source of innovation and R&D investment in Turkey for the last two decades (Berulava et al., 2019: 4).[3] The World Bank also highlights the fact that “the CU has closely integrated Turkish companies in European production networks for automobiles and clothing. It has helped raise the quality and sophistication of Turkey’s exports” (Ibid.). Overall, bilateral trade reached 147 billion dollars for the year 2012, making Turkey the EU’s sixth largest trading partner and the EU Turkey’s biggest trading partner (World Bank, 2014: 1).

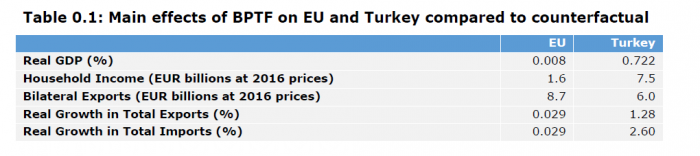

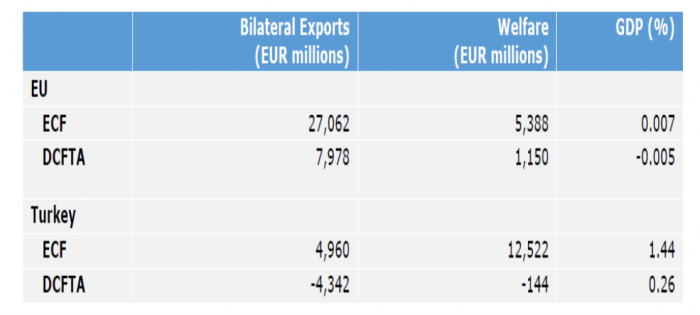

It should be noted that the impact assessment study for the European Commission highlighted an asymmetry in terms of the impact of the BPTF on the real output and economic welfare of the two parties involved (see Figure 2 and BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 12, 175-176). It was found that the gains for Turkey were substantially greater in both percentage and value terms. Specifically, Turkey’s real GDP rose by 0.722 and EU’s by 0.008% and the Household Income (EUR billions at 2016 prices) rose by 7.5 and 1.6 respectively.

Figure 2

Main effects of BPTF on EU and Turkey compared to counterfactual

Source: BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016, p. 12

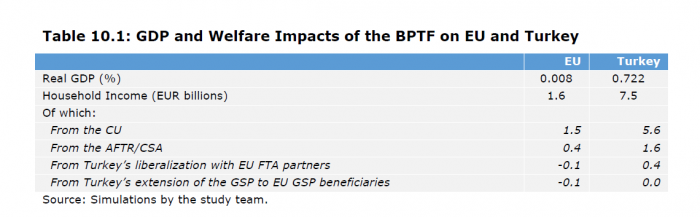

Finally, it was found that each element of the BPTF makes a positive contribution to Turkey’s real output and consumer welfare with the CU having the greatest positive effect through the reduction of trade costs (see Figure 3 and BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 76). Similarly, in the case of the EU, it was illustrated that the reduction of costs under the CU mainly accounted for BPTF’s contribution to output and welfare gains (Ibid.).

Figure 3

GDP and Welfare Impacts of the BPTF on EU and Turkey

Source: BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016, p. 176

Greek-Turkish Economic Relations during the BPTF Period

Overview

Greek-Turkish economic relations developed significantly in terms of trade, FDI, and tourism during the BPTF period. However, the data and the analysis below suggest that while the CU created the necessary regulatory framework within which Greece and Turkey could build their trade relations in a much more open way than before, it was only after the rapprochement between Greece and Turkey in the early 2000s and the commencement of Turkey’s EU accession negotiations that trust was built between politicians and business elites on the two sides of the Aegean. Specifically, it was between 2004 and 2006 that the total volume of trade rose by around 50%. It was around the same period that the largest bank in Greece, the National Bank of Greece (NBC), made the single biggest foreign investment ever made by a Greek firm. Similarly, tourist flows between the two countries surged after 2004. Therefore, one can argue that while the BPTF was a necessary condition for the enhancement of Greek-Turkish bilateral economic relations, it was not sufficient. The full potential of the BPTF started to be realised after the two countries, as well as the EU and Turkey, came significantly closer by building trust between the political and business circles on both sides.

Trade

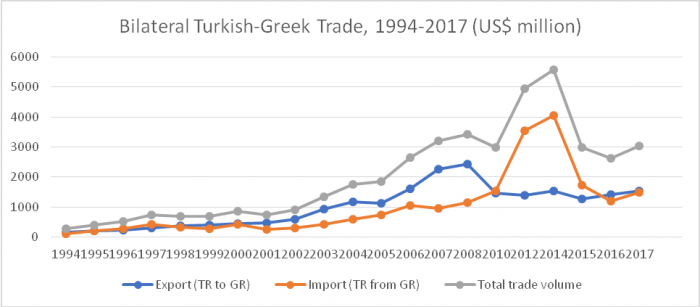

It was almost 10 years after the BPTF came into force in 1996 when Greek-Turkish bilateral trade increased exponentially (see Figure 4). Between 2004 and 2006, Greek exports to Turkey almost doubled (from $594 million dollars to $1.05 billion dollars) and Turkish exports to Greece rose by almost 30% (from $1.2 billion dollars to $1.6 billion dollars) (Tsarouhas & Yazgan, 2018: 10). In addition, the total volume of trade rose by around 50% (from 1.7 billion dollars to 2.6 billion dollars). The 2006 surge in trade appears even more dramatic when compared to 1989 and 1994 when the total volume of trade amounted to around $250 million dollars (Tsarouhas, 2009: 45). The 2006 surge was a tenfold increase.

“It was almost 10 years after the BPTF came into force in 1996 when Greek-Turkish bilateral trade increased exponentially.”

The Customs Union was a necessary regulatory trade framework for the two countries to develop their bilateral trade relations. However, as the data show, the big difference was made only after Turkey was designated an EU candidate country at the Helsinki Summit in 1999 and crucially the commencement of the EU accession negotiations in 2005 when the two countries broke the psychological barrier of hostile political relations and the resulting limited economic cooperation.

Figure 4

Source: Adapted from Tsarouhas D. & Yazgan N. (2018), Trade, non-state actors and conflict: evidence from Greece and Turkey, Cambridge Review of International Affairs, p. 10 and Tsarouhas D. (2009), The political economy of Greek–Turkish relations, Southeast European and Black Sea Studies, 9:1-2, p. 45

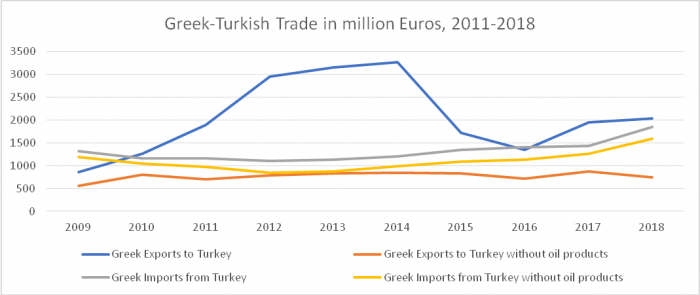

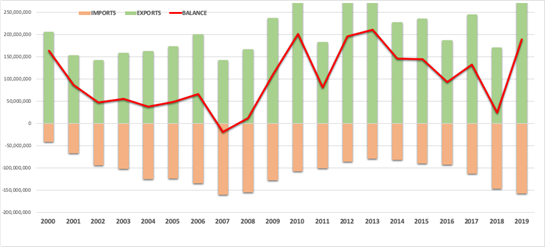

Considering the details of bilateral trade, the results are mixed for Greece. In the early years of the BPTF period, Greece run small trade deficits that increased between 2006 and 2010, as Figure 4 illustrates. This changed between 2010 and 2015 when Greece experienced significant trade surpluses. However, between 2009 and 2018, the balance of trade for Greece was negative in every single year bar oil products (see Figure 5; Makrygiannis & Laparidou, 2017: 32; Makrygiannis & Samouil, 2019: 35). The lack of trade diversity for Greece and its dependence on a single commodity, i.e. refined petroleum, means that the overall outcome of Greek exports to Turkey is sensitive to the performance of a single commodity and therefore can be highly volatile (see Figure 5). On the contrary, Turkey’s main exports to Greece include a wide variety of products making Turkish exports diverse and less prone to shocks.

Indicatively, in 2016, refined petroleum constituted 36% of Greece’s total exports to Turkey with raw cotton coming second with 8.5% (The Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2016a). In other words, two Greek products constituted 44% of Greece’s total exports to Turkey.[4] This explains why Greece experienced a steep reduction in its exports to Turkey by 21%, or 360 million Euros, with the reduction in oil exports reaching up to 28,2% or 246 million Euros and the reduction in raw cotton exports up to 34% or 53 million Euros (Makrygiannis & Samouil, 2019: 36). Consequently, the drop in oil exports and raw cotton exports accounted for more than 80% of the total drop in Greek exports for 2016.

In Turkey’s case, mineral products constituted 19% of all exports to Greece (i.e. refined petroleum 9.7%; petroleum gas, 8.1%), textiles constituted 16%, machines 13%, metals 12% and plastics and rubbers 9.4% (The Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2016b). The relative stability of Turkish exports to Greece and its upward trend can be observed in Figure 5, despite the volatility of the Turkish economy after 2011 (The World Bank, 2020).

Figure 5

Source: Adapted from Makrygiannis, C. & Samouil, Z., 2018 Yearly Report of Turkish Economy and Greek-Turkish Trade and Economic Relations, Greek Embassy to Ankara, 2019, p. 35 and from Makrygiannis, C. & Laparidou, N., 2016 Yearly Report of Turkish Economy and Greek-Turkish Trade and Economic Relations, Greek Embassy to Ankara, 2017, p. 32

“…Turkey has become a key trading partner to Greece in terms of its overall exports.”

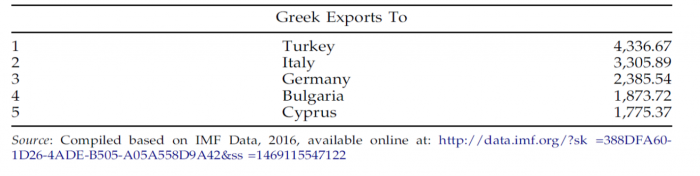

Importantly, Turkey has become a key trading partner to Greece in terms of its overall exports. For the years 2012-2014, Turkey was Greece’s primary export destination (see Figure 6; Tsarouhas & Yazgan, 2018, p. 9) and in 2019 Turkey was the 3rd most important export destination, absorbing 5.9% of Greece’s exports (Trading Economics, 2019a). At the same time, Turkey is also an important trading partner for Greece when it comes to imports. In 2019, for example, Turkey accounted for 3.6% of Greece’s imports ranking 8th in the list of import countries for Greece (Trading Economics, 2019b).

Figure 6

Greece’s exports partners, 2014 (US$ million)

Source: Tsarouhas & Yazgan, 2018, p. 11

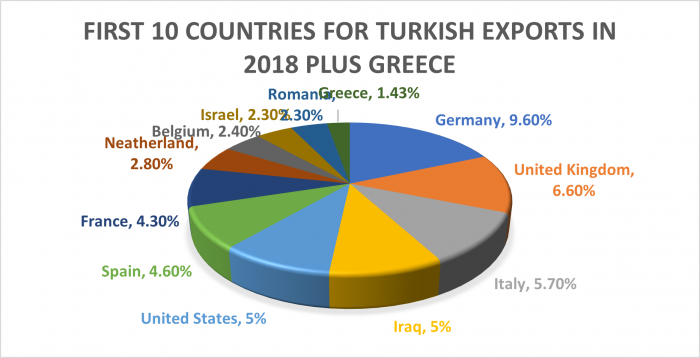

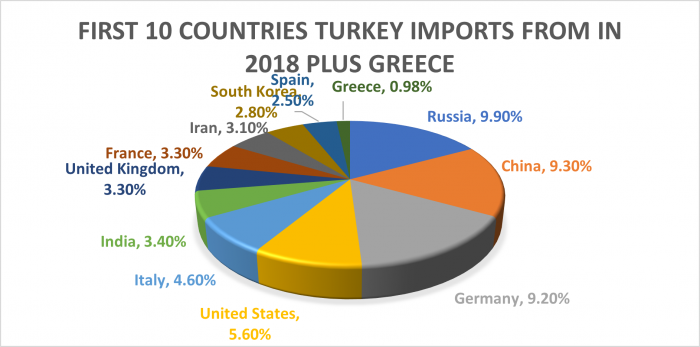

Greece, in turn, does not have the same prominence in Turkey’s exports/imports. For example, in the year 2006, Greece ranked the 15th most important export market for Turkey and 32nd in the list of countries from which Turkey imports (Papadopoulos, 2008: 13). More recently, Greece has improved its position, but not to the extent that it can be characterised as a key trading partner for Turkey. In 2018, the share of Turkish exports to Greece stood at around 1.4% bringing Greece 20th in the list of export destinations for Turkey trailing behind Israel (2.4%), Romania (2.3%) and Bulgaria (1.6%) (see Figure 7; Trading Economics, 2018a), while the share of Turkish imports from Greece stood at 1% bringing Greece 26th trailing behind the Czech Republic (1.3%), Bulgaria (1.2) and Romania (1.2%) (see Figure 8; Trading Economics, 2018b).

Figure 7

Source: Adapted from Makrygiannis, C., & Samouil, Z., 2018 Yearly Report of Turkish Economy and Trade and Economic Greek-Turkish Relations, Greek Embassy to Ankara, 2019, p. 22

Figure 8

Source: Adapted from Makrygiannis, C., & Samouil, Z., 2018 Yearly Report of Turkish Economy and Trade and Economic Greek-Turkish Relations, Greek Embassy to Ankara, 2019, p. 23

“…the implementation of the BPTF since 1996 has had a positive impact on Greek-Turkish trade relations compared to the period before, but its results would have been limited without the political rapprochement between the two countries.”

There are a couple of valuable conclusions that one can draw from the data so far. Firstly, the implementation of the BPTF since 1996 has had a positive impact on Greek-Turkish trade relations compared to the period before, but its results would have been limited without the political rapprochement between the two countries as part of Turkey’s EU candidacy, which started building political trust between them in the aftermath of 1999. Secondly, although both countries managed to increase their exports to each other, Turkey seems to have developed two advantages over Greece. The first is that Turkey has developed a diversified portfolio of exportable products, which guarantees stability in the overall volume of its exports to Greece. The second is that despite the fact that Greece exports to Turkey (2 billion Euros, 2018, see Figure 5) as much as it imports from Turkey (around 1.8 billion Euros, 2018, see Figure 5) Greece’s share of the overall Turkish exports/imports is miniscule compared to Turkey’s share of overall Greek exports/imports.

“Identifying sectors whose potential has not been unlocked under the current Customs Union – either because they were not included in the CU in the first place, such as primary agricultural products and public procurement, or due to Turkey’s poor implementation of its CU commitments – is key for Greece.”

Accordingly, Greek politicians and technocrats as well as the Greek business community would need to contemplate whether and how the modernisation of the Customs Union could provide answers to Greece’s trade weaknesses in the context of the current Customs Union. Identifying sectors whose potential has not been unlocked under the current Customs Union – either because they were not included in the CU in the first place, such as primary agricultural products and public procurement, or due to Turkey’s poor implementation of its CU commitments – is key for Greece to achieve trade diversification and a more sustainable trade surplus with Turkey in the coming years, especially now that the coronavirus pandemic is expected to hit the Greek economy hard and particularly affect sectors such as tourism (EKATHIMERINI, 14/04/2020; Institute of Touristic Research and Projections (ITEP), April 2020).

Foreign Direct Investment

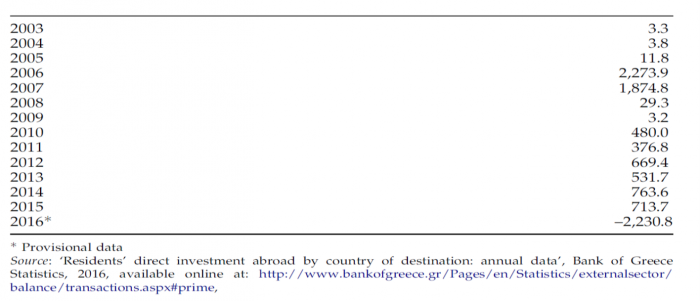

Similar to trade, it was not before 2004 and 2005 that Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and joint ventures took off, especially from Greece to Turkey. Indicatively, in 2003 and 2004, the Greek FDI stood at around 3.3 million Euros and 3.8 million Euros respectively. In 2005, Greek FDI rose to 11.8 million Euros, in 2006 to 2.3 billion Euros and in 2007 to 1.9 billion Euros (see Figure 9). Particularly in 2006, the acquisition of Finansbank by the National Bank of Greece was the main reason for the exponential increase of Greek FDI flows into Turkey. In addition, the Greek Eurobank acquired 70 percent of the Turkish Tekfen Bank. For the period of 2002-2007, Greece ranked 3rd in percentage of FDI behind the United States and Netherlands (Tsarouhas, 2009: 48).

“Similar to trade, it was not before 2004 and 2005 that Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and joint ventures took off, especially from Greece to Turkey.”

According to experts, the surge of Greek FDI to Turkey does not connect directly to the CU, but to the economic reforms that took place in 2001-2002 in Turkey and the commencement of the accession negotiations in 2005 (Interview with D. Giakoulas, 06.04.2020). Particularly, the National Bank of Greece saw an opportunity to invest in Turkey in 2006 just after the EU accession negotiations had commenced and Turkey started accumulating significant amounts of FDI (Ibid.). For the National Bank of Greece, the investment in Turkey was reminiscent of successful bank investments that took place in Central and Eastern Europe, including Balkan countries, before the ‘big bang EU enlargement of 2004 and 2007. Another point is that the highest percentage of Greek FDI by Greek businesses has been traditionally directed to countries that offered significantly lower taxation than Greece for changing tax residence, such as Cyprus and Bulgaria. This was not the case with Turkey (Ibid.). Therefore, one can argue that Greek companies invested in Turkey mostly because of the economic reforms in the country in 2001-2002, the commencement of EU accession negotiations in 2005, and the weakening of the Turkish lira during the last few years (Ibid.).

Figure 9

Greek FDI flows to Turkey (€ million)

Source: Tsarouhas & Yazgan, 2018, p. 11

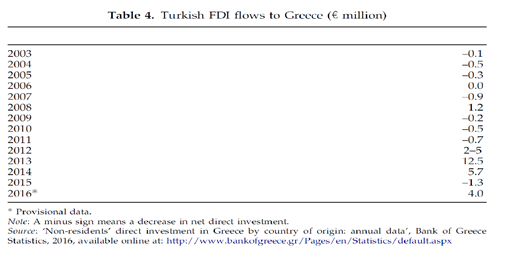

However, the Greek FDI inflows were not reciprocated by Turkish FDI in the early years (see Figure 10). The main reasons for that were that Turkish FDI preferred lower cost destinations and Greece had a bad record in attracting FDI in general due to bureaucratic obstacles in setting up a business, not least with regard to obtaining residence permits (Tsarouhas, 2009). Nevertheless, in the last few years, Turkish investments of around 400 million Euros have been made, particularly in tourism infrastructure in Athens and on the Greek Islands (Makrygiannis & Laparidou, 2017: 45; Makrygiannis & Samouil, 2019: 44-45). In addition, Ziraat Bank has opened offices in Athens, Komotini, Xanthi, and Rhodes since 2008.

Figure 10

Turkish FDI flows to Greece (€ million)

Source: Tsarouhas & Yazgan, 2018, p. 11

“…Greece can offer an opportunity for Turkish companies to collaborate on EU-funded projects and Turkey is a significant market that can open the doors to investments and public/private procurement biddings for projects in the Middle East and Central Asia.”

In terms of the number of Greek companies that were established and operated in Turkey, only nine existed in 2002. This number grew to fifty-eight in 2005 (Tsarouhas, 2009: 47). By the end of 2010, 439 Greek companies had invested capital in Turkey and in 2015 the number had increased to 686 and 752 in 2017 (Kontakos 2011, p. 4 in Tsarouhas & Yazgan, 2018, p. 12). Another facet of this cooperation are joint ventures, whereby Greece can offer an opportunity for Turkish companies to collaborate on EU-funded projects and Turkey is a significant market that can open the doors to investments and public/private procurement biddings for projects in the Middle East and Central Asia (Tsarouhas, 2009: 46). The successful bidding of a Turkish-Greek construction consortium in delivering the first phase of the Blue City project in Oman, a 20 billion project, is a case in point (Ibid.).

In the last few years, Greek FDI decreased significantly due to the Greek economic crisis that forced Greek banks to withdraw from the Turkish market (Interview with C. Papadopoulos, 17.01.2020). Up to 2015, the Greek FDI reserve in Turkey stood at 4.9 billion dollars and it dropped down to 113 million dollars in 2016 (Makrygiannis & Samouil, 2019: 44). Having said that, there are still several important Greek companies operating in Turkey, such as TITAN (cement), CHIPITA (food and beverages), ALUMIL (aluminium products), ISOMAT (insulation materials) and INTRAKOM (Information Technology). Similarly, the Turkish FDI reserves have also experienced a significant drop after 2014 (Ibid.). In 2013 and 2014, the FDI reserves stood at 52 million and 50 million dollars respectively. In 2015 and 2016, they dropped down to 25 million and 15 million dollars respectively, while in 2017 Turkish FDI reserves went up to 29 million dollars and again dropped slightly down to 26 million dollars in 2018.

“…to what extent could Greece possibly benefit from a modernised Customs Union in terms of absorbing significant FDI from Turkey in order to offset the adverse impact of Covid-19 on its economy?”

At this point, the main question that can be raised is to what extent could Greece possibly benefit from a modernised Customs Union in terms of absorbing significant FDI from Turkey in order to offset the adverse impact of Covid-19 on its economy? This question becomes even more relevant after the IMF’s dire projections for the Greek economy for 2020. The IMF reported in its Fiscal Monitor report that Greece’s GDP is projected to be -10% for 2020, its fiscal deficit will soar to 9% from a surplus of 3% and the general government’s debt is projected to jump to a staggering 200.9% for this year, only to fall to 194.8% next year (International Monetary Fund, April 2020).

Tourism

Tourism is a vital sector for the Greek economy and could be characterised as the locomotive of its economic growth. Its direct contribution to Greece’s GDP stood at 11.7% or 21,6 billion Euros in 2018, while its total contribution, including its multiplying effects on the Greek economy, was calculated between 25.7% and 30.9% of its GDP or between 47,4 billion Euros and 57,1 billion Euros (Ikkos & Koutsos, 2019: 14). Greek GDP grew by 2.5%, while touristic activity grew by 13.3%. 90% of its income came from international tourism proving its importance as an export industry. The sector directly employed 381.800 people in 2018 (The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020: 181) or according to some other estimations 650.000 people or 16.7% of the total number of people employed in Greece (Ikkos & Koutsos, 2019: 17).

Tourism is also an important sector for Turkey and has great potential to develop further. Its total direct contribution represented 3.8% of the GDP in 2018 and it directly accounted for 7.7% of total employment or 2.2 million people (The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2020: 293). The numbers of international tourists increased by 18.1% in 2018, reaching 45.6 million international tourists (Makrygiannis & Samouil, 2019: 45).

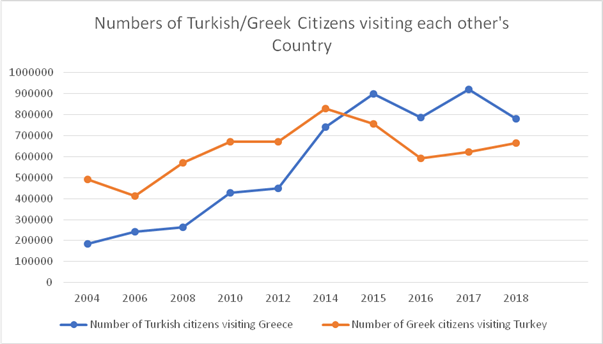

Tourism is also an important part of Greek-Turkish economic relations. The rapprochement between the two countries has been catalytic for the increasing numbers of tourists to each other’s country from the early 2000s on (see Figure 11). Indicatively, in 2000, 218.092 Greek citizens visited Turkey, while in 2004 the number went up to 500,000 (see Figure 11; Tsarouhas & Yazgan, 2018: 15). Similarly, 170.019 Turkish citizens visited Greece in 2003 and more than 400.000 in 2010 (see Figure 11; Ibid.). In 2018, 665.351 Greek citizens visited Turkey coming 9th on the list of different nationalities visiting Turkey for that year, whereas 781.753 Turkish citizens visited Greece, the second most popular destination for Turkish citizens (Makrygiannis & Samouil, 2019: 47-48).

Figure 11

Source: Makrygiannis, C., & Samouil, Z., 2018 Yearly Report of Turkish Economy and Trade and Economic Greek-Turkish Relations, Greek Embassy to Ankara, 2019, p. 23 and Tsarouhas & Yazgan, 2018: 14

As Covid-19 has spread around the world, Greece is facing an economic disaster. The IMF predicts a contraction of -10% for the Greek economy in 2020 (International Monetary Fund, April 2020), while other experts predict a fall between 7% to 18% (Economist, 11/04/2020). A big part of this gloomy picture can be explained by the stagnating number of international visitors. According to the Hellenic Chamber of Hotels survey, 95% of hotels operating throughout the year expect a reduction of 56.3% in their overall turnover and 94.2% of hotels that operate seasonally expect a 56.1% reduction in their overall turnover (Institute of Touristic Research and Projections (ITEP), April 2020). The total drop in hotels’ overall turnover is estimated at around 4.5 billion Euros, while 45.000 jobs are expected to be lost in the sector (Ibid.).

One can plausibly argue that the biggest reduction in arrivals will be of nationalities that use planes and ships to arrive in Greece, while neighbouring countries, such as Turkey, make primarily use of roads and if not, it is always an alternative. For visitors from Northern Europe, or even further away, it is difficult, if not impossible, to use this alternative. For example, from January to December 2015, 2.554.843 out of 2.810.350 German citizens and 2.370.791 out of 2.397.169 British citizens arrived by air, whereas only 102.304 out of 1.153.046 Turkish citizens used planes and 1.003.061 used vehicles of any sort (Hellenic Statistical Authority, 2016).

This is not to argue that the loss of the German and UK markets can be easily replaced with neighbouring markets, especially due to the fact that North Europeans are relatively high spenders. However, since Covid-19 has created uncertainty for the future of air travelling, it is imperative that Greece seeks ways to ameliorate its effects and improve prospects for its industry.

“Focusing on Turkey’s market can be one of the possible answers to the coming challenges, since it is vast in terms of potential numbers of visitors and Turkish citizens can easily access Greece via roads or short boat trips.”

Focusing on Turkey’s market can be one of the possible answers to the coming challenges, since it is vast in terms of potential numbers of visitors and Turkish citizens can easily access Greece via roads or short boat trips.

Having said that, there are three main challenges for Greece to consider. The first is that, as data has demonstrated, good political relations are of paramount importance. This is not dependent only on Greece and, as events have been unfolding since 2017, Greek-Turkish relations have entered a period of turmoil. Secondly, economic turbulence in Turkey and a weakening Turkish lira does not make Greece an attractive destination compared to non-Euro destinations, such as Bulgaria, Romania, and Georgia. Thirdly, although Greek citizens have been able to visit Turkey without visa requirements since 1985, the same is not true for Turkish citizens (Tsarouhas & Yazgan, 2018: 13). In 2010, Greece removed visa requirements for citizens with Green passports (state officials) and in 2012, Greece initiated a special visa to be acquired upon arrival to several Eastern Aegean islands during the summer period (Ibid.). However, these are piecemeal solutions that either apply to a very limited number of Turkish citizens that can easily obtain a visa or to most Turkish citizens but only for certain geographical areas during summertime.

The visa liberalisation dialogue between the EU and Turkey that started in 2013 was never completed due to Turkey’s refusal to revise anti-terrorism laws and sign legal cooperation agreements with member states, such as Cyprus (Kilic, 02/01/2019). Perhaps, the dialogue for the modernisation of the Customs Union could provide a new impetus to overcome the political and legal deadlock in the process.

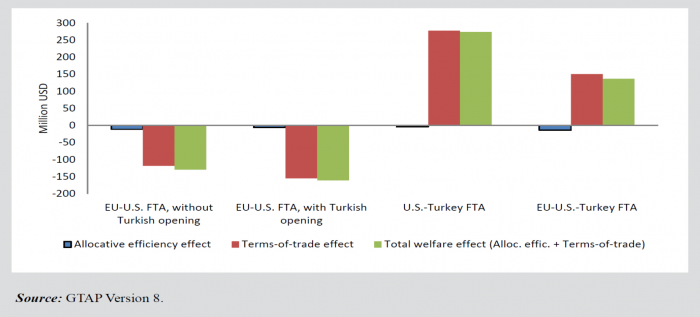

The Basis of the Discussion for an Upgraded Customs Union: The Gains for the EU and Turkey

There is a common understanding among economy experts and officials in the European Commission as well as in Turkey, such as the former Turkish Minister of Finance (2013-2015; 2016-2018), Nihat Zeybekci, that the existing EU-Turkey Bilateral Preferential Trade Framework (BPTF) has become outdated, especially when considering the Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreements (DCFTAs) that the EU has concluded or is negotiating with other economic partners. There is the EU-Korea Free Trade Agreement (FTA), the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the United States (BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 18; Mertzanis, 2017: 4). It is indicative that in one of its simulations the World Bank argued that if Turkey and the EU were able to agree an FTA with the US in the context of the TTIP, the Turkey’s welfare would increase by US$ 130 million, while an EU-US FTA that would not include Turkey, would cost the country US$ 130 million in the no-trade deflection via the EU scenario and 160 million if US trade is deflected via the EU and becomes duty free (World Bank, 2014, p. 27; see Figure 12).

There is a common understanding among economy experts and officials in the European Commission as well as in Turkey, such as the former Turkish Minister of Finance (2013-2015; 2016-2018), Nihat Zeybekci, that the existing EU-Turkey Bilateral Preferential Trade Framework (BPTF) has become outdated.”

Figure 12

Simulated welfare effects for Turkey from an EU FTA with the U with and without unilateral removal of Turkish tariffs and with and without inclusion of Turkey/the EU in the FTA

Source: World Bank, 2014, p. 27

The dialogue on the modernisation of the CU started in 2014 and in December 2016 the European Commission completed its working document recommending authorisation of the opening of negotiations with Turkey (Berulava et al., 2019: 5). The working group recommended that “the existing CU be modernised, that trade in agricultural and fishery products be further liberalised, and that the framework be additionally enhanced to cover, inter alia, services and public procurement” (BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 18).

So far, it is only the impact assessment of the modernisation of the BPTF that has been agreed upon and delivered to the EU Commission. The opening of the negotiations is still pending a decision on the part of the EU Council to provide the Commission with the necessary mandate for the commencement of the process.

The report prepared for the EU Commission in 2016 studied the impact of three different scenarios on the future of EU-Turkey trade relations, i.e. “no policy change”, “CU modernisation and FTA in additional areas” and “Deep Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement”.

“The main conclusion was that “a Modernised Customs Union plus an FTA covering services, public procurement, and further liberalisation in agriculture” is the best option from an economic and regulatory point of view.”

The main conclusion was that “a Modernised Customs Union plus an FTA covering services, public procurement, and further liberalisation in agriculture” is the best option from an economic and regulatory point of view (Berulava et al., 2019: 5-6; see Figure 13). The main reason is that this scenario is estimated to boost GDP growth for both parties, albeit larger for Turkey, and provides the opportunity to fix design deficiencies of the CU (BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 16; see Figure 12).

The “no policy change” scenario is likely to harm trade between the two partners, according to the report, “due to poor implementation standards on the Turkish side and the non-functioning dispute resolution mechanisms” (Berulava et al., 2019: 5-6).

The third option of a DCFTA removes the legal obligation for Turkey to align itself with EU policy and creates only the commitment, while at the same time Turkey would be able to negotiate trade agreements with third parties alone. It was also found that the third scenario would be economically less beneficial (Ibid.; see Figure 13).

Figure 13

Main impacts of scenarios for enhancing the BPTF

Source: BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016, p. 16

In 2016, the then Turkish Minister of Finance, Nihat Zeybekci, argued that the scenario of a full modernisation of the CU which would include agriculture, services, and public procurement, would improve Turkey’s GDP by 2% until 2030 and would increase Turkey’s exports to the EU by 24.5% and its imports from the EU by 23% (Greek Office of Economic and Commercial Affairs to Ankara, 29/12/2016). He expressed his preference for that option instead of others that were less ambitious (Ibid.). This demonstrates that both parties were on the same page in terms of the economic analysis and the benefits of a modernised Customs Union for the two partners.

“…an upgraded/modernised CU will create the opportunity to resolve issues that have emerged from Turkey’s poor implementation of its commitments deriving from the current CU.”

In addition to the removal of tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade in various sectors, such as public procurement, which would benefit European companies, a closer trade relationship could help the EU to regain its position as a point of reference for Turkey. Thus, it would enhance its political capital. More tangibly, an upgraded/modernised CU will create the opportunity to resolve issues that have emerged from Turkey’s poor implementation of its commitments deriving from the current CU (Interview with C. Kamitsi, 15.01.2020). Nevertheless, it has also been argued that the implementation problems could be resolved within the parameters of the current CU (Interview with C. Papadopoulos, 17.01.2020).

The main gains for Turkey can be summarised as economic and regulatory (see more in Berulava, Manoli, & Selcuki, 2019: 5-6). According to the report prepared for the Commission, an upgraded commercial framework could raise welfare in the EU and Turkey by 5 billion euros and 12 billion respectively; twice as much for Turkey. In addition, potential welfare gains from the opening vis-à-vis agricultural products and services in the CU is estimated at 1.44% additional benefit for Turkey’s GDP (BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 16; see Figure 13).

“modernisation of the CU and its proper enforcement can potentially serve Turkey’s interests as preparation for the mega-trade agreements, such as the TTIP and CETA.”

In addition, an upgraded CU could possibly address the decision-making asymmetry between Turkey and the EU. Currently, the EU is permitted to negotiate FTAs with third countries, but Turkey is not permitted a seat at the negotiating table because it is not an EU member. This increases the risk of no-compliance on the part of Turkey. In the no policy change scenario, it is deemed likely that trade between the two partners would be harmed due to poor implementation standards on the Turkish side and the non-functioning dispute resolution mechanisms (World Bank, 2014: ii). Most importantly, modernisation of the CU and its proper enforcement can potentially serve Turkey’s interests as preparation for the mega-trade agreements, such as the TTIP and CETA.

In terms of specific sectors, agriculture features as one of the most prominent in terms of tangible gains for the Turkish economy.[5] Presently, trade of primary agricultural products is subject to tariff quotas, price regulation, and various bureaucratic obstacles, which have produced a high degree of protectionism in both the EU and Turkey. There are three studies that support the idea that an opening of the agricultural sector would benefit Turkey’s GDP and productivity.

To begin with, the European Commission’s report argues that “increased market access under the ECF, including in the area of primary agriculture, is estimated to lead to welfare gains for Turkey of approximately EUR 12.5 billion” (BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 222). The argument is based on the idea that protection of primary agricultural products under the BPTF resulted to a less efficient economy and thus smaller gains “that otherwise would have been possible” due to reduced structural adjustment (Ibid.: 180, 236). The report also highlights that protectionism in agriculture “worked to the disadvantage of Turkey’s downstream food-processing sector” (Ibid.: 10). There is also data that shows that the FDI for primary agriculture, forestry, and fishing has attracted 0% of FDI between 2007 and 2015 (Ibid.: 47). On the other hand, the report acknowledges that “adverse impacts on rural employment are likely, thus potentially reducing the standard of living of small-scale farmers” (Ibid.: 222-223).

The World Bank report, in turn, suggests that simulations employing a Computable General Equilibrium (CGE) model to investigate the impact of differing scenarios on deepening the trade agreement with the EU in primary agriculture showed increase in real income in Turkey and the EU under all scenarios, although it was also acknowledged that there could be adverse impact on rural employment (see more in World Bank, 2014: 64, 125). The third study suggests that “agricultural exports to the EU are forecast to rise by 95%” (Felbermayr, Aichele, & Yalcin, 23/07/2016).

Finally, the modernisation of the CU can ensure that the BPTF will not continue to lag behind the EU’s most ambitious procurement agreement, namely CETA, by recognising public authorities the discretion to include specific provisions that effectively restrict the participation of foreign companies in tenders[6] and not including anti-fraud provisions (BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 22, 140-141). The reforms could help enhance healthy competition between Turkish companies and allow for competition between Turkish and European companies in order to achieve better economic and technical results.

What are the potential gains (i.e. incentives) by an upgraded/ modernized Customs Union for Greece?

As already discussed, the BPTF gave the opportunity to both countries to develop their trade relations by removing tariff and non-tariff barriers. However, there have been differences in terms of the actual configurations of their trade relations. These differences give the impression that Greece could and should further develop its potential for exports in case the chance for a modernised CU arises. Specifically, while Greece increased its exports to Turkey and even developed trade surpluses between 2010 and 2015, it has not managed to diversify it. To the contrary, its exports are highly dependent on a single commodity, i.e. refined petroleum, and therefore the total volume of Greece’s exports is sensitive to its fluctuations. Secondly, Greece has not managed to become an important trading partner to Turkey relative to its size. In addition, it trails behind the Czech Republic, Bulgaria, and Romania, while Turkey has succeeded in becoming a key trading partner for Greece. In this context, an upgraded/modernised CU could create opportunities for Greece to diversify its exports to Turkey and increase its share in the list of countries from which Turkey imports.

One of these opportunities is the possible inclusion of primary agricultural products to a modernised CU. Accordingly, Greece’s aim would be to diversify its portfolio of exporting products and enhance its presence in the total share of Turkey’s imports.

“…within the parameters of the current CU, Greece has managed to develop a trade surplus in agriculture throughout the years, from 2000 to 2019 (only exception 2007 and 2018.”

A common belief is that opening trade for primary agricultural products means that Mediterranean countries, including Greece, will face increasing competition from Turkey in edible vegetables, fruits, and other processed agricultural products with unknown consequences for Greece’s agricultural sector (Mertzanis, 2017: 4; World Bank, 2014: ii). So far, within the parameters of the current CU, Greece has managed to develop a trade surplus in agriculture throughout the years, from 2000 to 2019 (only exception 2007 and 2018; see Figure 14; Interview with S. Klonaris, 14/04/2020). In addition, it is argued that Greece would not face severe competition by similar Turkish products in the EU in the medium-term, since it has developed the know-how in implementing EU rules on food safety, veterinary, and phytosanitary issues as part of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) (Interview with S. Klonaris, 14.04.2020; World Bank, 2014: ii). At the same time, Greece can possibly export high quality processed products which are currently excluded from Turkey’s internal market due to the extremely high tariffs that are implemented possibly in contravention of the current CU. For example, Greece is the biggest producer of extra-virgin olive oil globally. 11% of its total exports to Italy, the second biggest producer in olive oil in the world, is extra-virgin olive oil. Turkey implements a 32% tariff on extra-virgin olive oil. In addition, Feta Cheese, a strong brand name worldwide, faces a 180% tariff. Finally, it has been estimated that due to trade barriers in agriculture Greece has lost 1.5 billion Euros in the years of 2004-2013 (Interview with S. Klonaris, 14.04.2020).

“…Greece is the biggest producer globally in extra-virgin olive oil. 11% of its total exports to Italy, the second biggest producer in olive oil in the world, is extra-virgin olive oil.”

Figure 14

Balance of Trade in Agricultural Products in terms of Greece’s Exports/Imports to Turkey, 2000-2019

Source: Eurostat, EU Trade Since 1988 By SITC (DS-018995)

Moreover, an upgraded/modernised CU that includes services, such as public procurement, could create opportunities for synergies between Greek, Turkish, and other European companies for the delivery of large-scale public projects in Europe and in Turkey (Papadopoulos, 17.01.2020). In particular, the liberalisation of visa for Turkish citizens in the context of the modernisation of the CU would possibly enhance FDI investments from Turkey to Greece (Interview with D. Giakoulas, 06.04.2020).

“…the strengthening of labour rights in Turkey means better conditions of competition between Greek and Turkish companies in terms of costs.”

Furthermore, if in the name of liberalising services further the transfer of goods through Turkish ports (cabotage) can be carried out by the European merchant fleet, it will benefit Greece’s merchant fleet too, one of the biggest in the world (C. Papadopoulos, 17.01.2020). It will also give incentives to Greek shipowners to consider registering their ships under the Greek flag. In addition, the strengthening of labour rights in Turkey means better conditions for competition between Greek and Turkish companies in terms of costs (Ibid.).

From an environmental point of view, an upgraded Customs Union might translate into stronger efforts to protect the Aegean Sea from industrial and urban pollution (Ibid.), although the Commission’s report acknowledges that under a modernised CU framework the impact on the environment will be mixed (BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 234).

What are the preconditions for Greece to accept an upgraded/ modernized Customs Union?

The probability of Greece giving the green light for negotiations between the EU Commission and Turkey to begin depends crucially on political and less on economic arguments. Indeed, security and political concerns override any discussions over economic relations with Turkey and those views cut across the political spectrum, the business community, the bureaucracy, and the experts.

“The probability of Greece giving the green light for negotiations between the EU Commission and Turkey to start depends crucially on political arguments and less on economic.”the

After a brief period of “Halcyon days” that followed the EU Helsinki decision in 1999, also known as the “Golden Years of Turkey’s European path” (2001-2004), Greek-Turkish relations are again deteriorating, as the freezing of Turkey’s accession process (2006) led to a growing interest within Turkey to follow a more independent (less EU) and more ambitious Middle East-oriented and “security-based”, rather than “interest-based”, foreign policy.

Particularly over the last three years, especially after the failed military coup in 2016 and the Presidential elections in 2018, Erdogan’s “New Turkey” has adopted an aggressive and revisionist policy vis-a-vis Greece through the projection of hard power against both Greece and the Republic of Cyprus. Since the attempted coup Turkey, according to the Greek government, has abandoned a “security-based” foreign policy (with certain ambitions vis-a-vis its periphery) and has moved further down the path of a “power-based” foreign policy that exhibits the same pattern of aggressive behaviour in Cyprus, the Aegean, and Libya (statement by the Greek Minister of Foreign Affairs, Nikos Dendias).

“The reading of the Greek government about Turkey’s behavior (interestingly this reading transcends the political spectrum horizontally) is that Turkey is sliding from “one-man regime” to an ”illiberal democracy”, further distancing itself from the West (US, NATO) and particularly from the EU.”

The Greek government’s reading of Turkey’s behaviour (interestingly this reading transcends the political spectrum horizontally) is that Turkey is sliding from an “one-man regime” to an ”illiberal democracy”, further distancing itself from the West (US, NATO) and particularly from the EU, the latter not constituting a “strategic priority” for Turkey and in consequence, Turkey is not willing to sacrifice much for its European vocation. Moreover, according to the Greek government’s assessment of Turkey’s behaviour on the Greek-Turkish borders on the river Evros in northern Greece in late February-early March 2020, the refugee/migration challenge has proved less of a driver of cooperation between Turkey and Greece/EU and more of a strong leverage for Turkey that promoted short-sighted policies through the “instrumentalization” of migrants and refugees.

The emergence of Greece and particularly Cyprus as key-players in the Eastern Mediterranean with regard to the exploitation and transfer of gas to Europe has led to Turkey’s harsh reaction. However, Turkey’s decision to purchase its own drilling vessels and the beginning of its own explorations in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of Cyprus is hardly seen by Greece as Turkey’s reaction to attempts made by Greece and Cyprus to isolate Turkey from energy developments in the Eastern Mediterranean through the construction of the EastMed natural gas pipeline and Cyprus’ delimitation agreements with Egypt, Lebanon, and Israel. Indeed, for the majority of Greek decision makers and security analysts this is actually a manifestation of a new phase of “neo-ottomanism”, which has taken the form of “Mavi Vatan” (“Blue Homeland”), namely the area upon which Turkey claims it has sovereign rights although this includes parts of the continental shelf of Cyprus, as well as a series of big Greek islands, such as Rhodes, Karpathos, Kasos, as well as the eastern part of Crete.

Moreover, Turkey’s direct involvement in the Libyan civil war and the November 2019 signing of a military and maritime zone delineation agreement between the government of Turkey and the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA) sparked harsh reactions in Athens, as the agreement infringed upon maritime zones adjacent to the Greek islands of Crete, Kasos, Karpathos, Rhodes, and Megisti (purposefully violating the principle of international law that islands are taken into account when delineating an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ)). This agreement not only led to the interruption of relations between Athens and Tripoli, but also supports the theory that serious tensions could arise around Cyprus that could reignite dormant Greek-Turkish tensions over the delineation of maritime zones. Greece’s diplomatic campaign immediately after the signing of the Turkey-Libya MoU aimed at making it null and void. To this end, Greece has managed to form a broad delegitimization front against the agreement with the participation of various states and international institutions (most notably the European Union), declaring that the MoU is against international law, it does not have legal consequences, and it violates the sovereign rights of the states in the region. Yet, according to the Greek Minister of Foreign Affairs, the diplomatic campaign undertaken by Greece was not about creating an “anti-Turkish front, but a front of reason.”[7]

“…it is difficult to see how Greece could positively approach the commencement of an upgraded/modernized Customs Union as a way of coming to terms with the “New Turkey”, all the more so given that an upgraded CU does not offer any political and security guarantees for Greece.”

Within such an environment of harsh confrontation it is difficult to see how Greece could positively approach the commencement of an upgraded/ modernized Customs Union as a way of coming to terms with the “New Turkey”, all the more so given that an upgraded CU does not offer any political and security guarantees for Greece in case relations deteriorate further with Turkey (BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 234). Economic benefits deriving from an upgraded/modernised CU are potential and long-term, while the adverse effects of Turkey’s behaviour vis-à-vis Greece are real and present. In other words, it is almost impossible to see how Greek politicians would invest political capital in an endeavour that is uncertain and long-term in its benefits, while incurring instantaneous losses to their public image due to Turkey’s current behaviour.

Therefore, any economic potential for Greece arising from a modernised CU – even if the country experiences a severe economic downturn due to Covid-19 – would not sugar the pill of serious security concerns deriving from Turkey’s non-constructive, reckless behaviour vis-à-vis migration issues, the Eastern Mediterranean, and Libya.

Thus, according to the Greek government (PM Mitsotakis, 20.07.2020), the ruling party of New Democracy (Bakoyanni, 16.12.2019) and, most interestingly, Greece’s major opposition party (SYRIZA) for Greece to accept an upgrade of the CU the easing of political tensions with Turkey, the cessation of Turkey’s aggressive and illegal behaviour vis-a-vis Greece in the Aegean and in the EEZ of Cyprus, and the prior opening of the Turkish ports to the Republic of Cyprus remain essential prerequisites (Interview with E. Kalpadakis, 20.01.2020). Moreover, Greek politicians from the right, centre-left, and left political parties (ND, KINAL, and SYRIZA) are keen to stress that the significant deterioration of Greece’s political relations with Turkey in the last few years due to the Aegean and Eastern Mediterranean disputes have made it hard for them to overlook the Greek public’s negative perception of Turkey.

Specifically, the deterioration of political relations between the EU and Turkey as well as Greece and Turkey loom large in the public sphere. A case in point is a recent (December 2019) poll conducted by the Public Opinion Research Unit, University of Macedonia, which revealed that the absolute majority of the Greek public considers Turkey as the gravest threat for the country (89% compared to 64,5% in the beginning of 2018). What is more interesting, however, is the fact that the electorate’s perception and feelings regarding Greece’s stance towards future relations with Turkey are positive, by being in favour (64%) of a pragmatist approach that promotes bilateral dialogue with Turkey as well as further anchoring Turkey in the EU. Yet the latter cannot take place for as long as Greek-Turkish bilateral relations keep deteriorating and Turkey keeps following a threatening, provocative, and illegal behaviour vis-a-vis two EU-members, namely Greece and the Republic of Cyprus.

“…the governing party along with the parties of the opposition seem to agree on a “transactional logic” with regard to the commencement of negotiations between the EU and Turkey for a modernization of the CU.”

With the above preconditions being first fulfilled, the governing party (New Democracy) along with the parties of the major (SYRIZA/Coalition of the Radical Left) and the minor (KINAL/Movement for Change) opposition seem to agree on a “transactional logic” with regard to the commencement of negotiations between the EU and Turkey for a modernization of the CU (Interviews with P. Ioakimidis, 16.01.2020; E. Kalpadakis. 20.01.2020). Specifically, all three parties appear receptive to sound out the possibility of an upgraded Customs Union provided that certain political conditions will also be attached to it. To this end, Greece would have accepted the commencement of negotiations between EU and Turkey had these led to a “Customs Union Modernization Plus”, namely the incorporation of certain issues of particular importance to Greece, most notably related to security, defence, and migration. Needless to say that Greece would also be in favour of the introduction of any kind of conditionality that would tie economic cooperation between the EU and Turkey to the fulfilment of certain conditions regarding human rights, democracy, and respect of the rule of law.

Interestingly enough the views of the business community, the bureaucracy, the security analysts, and foreign policy experts in Greece seem mostly to resonate with the views/rationale of the decision makers with regard to the launch of negotiations for an upgraded Customs Union between the EU and Turkey. More specifically, diplomats in the Greek Foreign Ministry express ideas that are in full conformity with the ideas that decision-makers have in mind, i.e. security and political concerns that override any discussions over economic relations with Turkey. In addition, highly-ranking diplomats do not reject the idea that modernisation of the Customs Union is a necessary step for the EU and Greece to resolve any outstanding issues with Turkey in the field of trade, yet they are hesitant to discuss any alternative other than the accession negotiations with Turkey.

The officials in the Ministry of Agriculture seem to believe that Greece would gain from the modernisation of the CU in the field of agriculture. They tend to emphasise the potential of Greek agriculture. However, they do not seem open to sharing their views publicly, not to mention promoting their ideas to higher levels of decision-making.

The Greek business community would be in favour of deepening the CU since it has helped them to connect with the business community in Turkey and develop a number of projects in Turkey and joint ventures in the Middle East. There are still hundreds of active Greek companies in Turkey. They have tried actively in the past to promote better Greek-Turkish relations through their support to Greek governments in relation to the designation of Turkey as an EU candidate country as well as other civil society initiatives. Now, this activity seems to have ceased. There is disorientation and lack a coherent view as to how they could possibly promote better Greek-Turkish relations, since Turkey is sliding towards authoritarianism, Turkey’s accession negotiations have been derailed, and Turkey projects hard power against Greece and Cyprus. It is very difficult to see how members of the Greek business community can actually affect the Greek government’s decisions in keeping a less critical tone when it comes to Turkey. It is also disheartening for them that Turkish business associations are overwhelmed by the sheer power of Erdogan’s presidential system.

Last but not least, the Greek security analysts and foreign policy experts have developed opinions about what could be the gains and losses for Greece from a modernised CU, but they cannot affect decision-making substantially due to a lack of strategic thinking on the part of Greek governments when it comes to Turkey. The old has died and the new has not been born in relation to Turkey’s accession negotiations. Greek governments try to react on a day-to-day basis without any long-term strategy in sight. Unfortunately, the EU seems to function under the same line of reasoning by concluding ad hoc agreements with Turkey, such as the EU-Turkey statement on migration, that have failed to deliver medium-term positive results.

[1] Article 33 of the Additional Protocol provided for a 22-year period for Turkey to “adjust its agricultural policy with a view to adopting, at the end of that period, those measures of the common agricultural policy which must be applied in Turkey if free movement of agricultural products between it and the Community is to be achieved.” Article 34 then provided for free movement of agricultural products if the stipulated conditions were met. (BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 20).

[2] The economic plan undertaken by the Turkish government at the time focused on two aspects: fiscal discipline and structural reforms, and included, among others, protection of public banks from government interference, institutionalization of independent oversight of the private banking sector, and actual independence of the central bank (Dervis, 29/04/2002).

[3] Rating agencies and international investors take the EU-Turkey relationship into account when deciding on the risk of financial flows to Turkey (See Cömert, 2017: 19).

[4] In 2007, the percentage was even higher with refined petroleum occupying 49% of Greek exports and raw cotton 8.5%. This amounts to almost 60% of Greece’s total exports to Turkey (The Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2017).

[5] Agriculture is an important sector of the Turkish economy in terms of its share of GDP and the number of people it employs. It covers 10% of Turkey’s GDP and one quarter of employment. It is mainly dominated by small-scale family farms (BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016).

[6] The Turkish public procurement regime, as it stands today, does not limit the participation of foreign undertakings in theory (BKP Development Research and Consulting et al., 2016: 140).

[7] “We want the countries that have a say on and involvement in regional issues to have complete awareness of the Greek positions and understand that we represent the voice of reason” (Dendias, 2020).