- The X and X decision of the European Court of Justice highlighted the gap in current EU law regarding human rights protections in entry procedures.

- Currently over 90% of those granted refugee status in the EU arrive through irregular means.

- There is an increasing need for a new form of visa, specifically to accommodate humanitarian matters, which are not currently covered by the pre-existing Schengen rules.

- For limited numbers, consulates of EU states would be empowered to issue Visas for asylum seekers in order to legally cross EU borders to launch an asylum application.

- Research shows that the economic costs for the implementation of this humanitarian visa system would be minimal and that the political and humanitarian benefits would be significant.

You may find here in pdf the Policy Paper by Eleni Kritikopoulou and Jason Dougenis, Junior Research Assistants at ELIAMEP’s Migration Programme.

Introduction

The legacy of the refugee crisis of 2015 is largely considered to be the rise of anti-immigrant and right-wing politics (European Parliament, 2018). However, its largest impact, was in exposing the incoherence of EU’s migration and asylum policy. The lack of a coordinated response, the unilateral suspension of the Dublin rules by Germany for Syrians, and the onward movement of refugees through the Western Balkan route from Greece led to an erosion of trust between member states.

Having a common asylum policy is one of the fundamental features of the European Union as per Article 78(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union. However, asylum policy continues to fall short of providing legal pathways of entry for asylum seekers. Following the “migration crisis” of 2015, the situation has deteriorated. Member states have been reluctant to admit more asylum-seekers, as they were discursively constructed as a security threat (Maldini & Takahashi, 2017). The focus has been on deterrence rather than establishing multiple pathways of legal entry for those most vulnerable.

“For asylum seekers, there is almost no other option but irregular journeys, as there are currently no consistent Protected Entry Procedures into the European Union.”

In 2015, over 90% of those who were subsequently granted international protection in the European Union arrived through irregular means (European Parliament, 2016). Despite the reduction in arrivals, asylum applicants continue to have limited options but to enter unauthorized, resulting in the loss of human lives; since 2000, over thirty thousand lives have been lost at sea attempting to cross into the European Union (ibid). For asylum seekers, there is almost no other option but irregular journeys, as there are currently no consistent Protected Entry Procedures into the European Union.

The most common form of PEP is refugee resettlement programmes that relocate a number of UNHRC-recognised refugees from a third country to the European member-state (Morelo-Lax, 2018). Another form of PEP is private sponsorship programmes of refugees by either NGOs or individuals, which are often linked with family reunification (ibid). Both of these options require that the person in question has already received refugee protection and is being resettled in order to alleviate pressure from the hosting country. The current PEPs, are characterised by inconsistency, rely on State discretion, and remain largely underused, damaging the Union’s coherence regarding asylum policy.

“There should be common European rules that empower states to issue Visas to their territory for the explicit purpose of lodging an asylum application.”

The paper explores the possibility of establishing a Humanitarian Visa system as a viable addition to the asylum system currently in place in the European Union. Though difficult in the current political environment, it is still worth exploring whether the creation of a new Protected Entry Procedure (PEP) through the introduction of a common standard for a ‘humanitarian’ or ‘asylum-seekers’ Visa, could function as a viable legal pathway of entry to the EU. There should be common European rules that empower states to issue Visas to their territory for the explicit purpose of lodging an asylum application. These visas would be limited territorially (a type of limited territoriality visa already exists in the Schengen Code) so as to maintain control and effective monitoring of the system, while the legal principle of non-refoulement would be integrated in the visa. Thus, a legal pathway to asylum in the European Union would be established targeting those most vulnerable but also most likely eligible for protection on the basis of an initial pre-screening. This would mean that the system in question would only be able to accommodate a small number of applicants per year and would not function as a replacement but rather complement refugee resettlement programmes for those that cannot wait for months and/or years.

The discussion below serves as a starting point, with some suggestions for how such a system could be structured, is a first step in an effort to resuscitate an issue that has been side-lined in the past few years between Member States. Ιt is in the benefit of the member states to consider expanding and implementing existing but also new PEPs.

Why should States participate?

According to the European Parliament’ s Civil Liberties Justice and Home Affairs “the absence of ‘protection-sensitive’ mechanisms for accessing EU territory, against a background of EU extraterritorial border/migration management and control, undermines Member States’ refugee and human rights obligations” (Jensen, 2014). By reinforcing PEPs, the EU would be closer to meeting its obligations towards refugees while also balancing the needs of member states for orderly migration.

“Operating under the same list of regulations and the same policy framework would lead to a more coherent Union and thus better cooperation in the future.”

Operating under the same set of regulations and the same policy framework would lead to a more coherent Union and thus better cooperation in the future. After all, some member states already make use of PEPs. It is also vital to consider the increased cooperation between member states and countries of transit that would emerge from a functioning common humanitarian entry system, a positive investment in the external dimension of migration.

Through a pan-European system with a common framework and common rules, more efficient numbers management could occur, and far less focus on European borders and border procedures. Additionally, as arrivals would be more efficiently monitored, Member States would have a better estimate of numbers entering their borders at any given moment, allowing for national reception and integration systems to also be better prepared.

The economic cost of current border management is such that alternatives or the creation of a bigger variety of options may prove to be more viable and financially sustainable for member states.

“Having common rules on Protected Entry Procedures would strengthen public trust towards the Union.”

Having common rules on Protected Entry Procedures would strengthen public trust towards the Union in matters of migration and at the same time it would prevent asylum being politicised either by anti-immigrant populists or by countries instrumentalising asylum for their bilateral relations with third countries.

Τhe economic cost of the current system

Economic viability and cost-effectiveness are critical parameters. The status quo of the current system, can be understood as “the present limited availability of legal channels for asylum seekers in third countries to pursue asylum applications in the EU” and is associated with “significant costs” (EPRS, 2018). Hence, it is important, when examining such a proposal, to understand the economic limitations of the current status quo and how those may overshadow its benefits, in order to be able to justify the need for a new type of method.

Integrated border management, produces high costs which affect both the EU and Member States,. According to the European Commission, more than 1.8 million irregular border crossings were detected in 2015 alone and in the next long-term budget period (2021-2027) the EU is planning to spend 34.9 billion Euro on border security, almost triple than the previous period (16 billion Euro) (EC, 2018). This results in a booming business for Europe’s border security industry, due to the increasing militarization of borders and funding of private security firms, such as the Italian security firm ‘Leonardo’, which was awarded a €67.1m contract in 2017 by the European Maritime Safety Agency to supply drones to the EU coastguard agencies.

Moreover, it is important to remember that the cost for safeguarding borders, falls disproportionally on the frontline states, Italy and Greece. The latter’s national expenditure on border control remains quite high despite the extensive contribution from the Internal Security Fund.

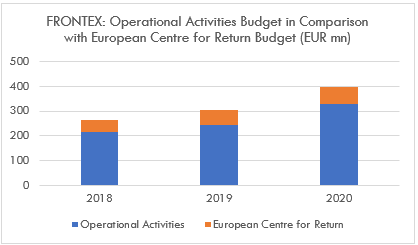

Figure 1: Author’s own composition of European Commission numbers (European Commission – DG Home, 2017)

Apart from large funds being invested in combatting smuggling on EU borders, there are other operations that the EU spends significant sums on that stem from the absence of legal pathways to Europe and from the broader management policies of irregular migration. These are rescue operations for people at sea, detention centres, assisted return to irregular migrants and/or rejected asylum seekers to their countries of origin and transit.

Figure 2: Author’s own composition of FRONTEX numbers

One such example is the funding of the European Border and Coast Guard Agency (FRONTEX) that has increased substantially in the last few years. In 2020 about 20% of funding for operational activities (459 million Euro in total) was budgeted for the European Centre for Return (Figure 2). Returns are a priority for the EU, partly due to the limited success of returns to third countries Additionally, it has been estimated that there is a cost of about 216,000 Euro per rescue operation.

A humanitarian visa system – could be a far more sustainable solution to addressing the security concerns of member states, and to counter smuggling since it would establish much needed legal pathways. It would reduce incentives for irregular journeys for those in need, it would reduce dangerous and often fatal journeys, and it would gradually allow for the growth of a European asylum system that would be based on a true balance between reduction of irregular migration and protection for asylum applicants. This has been previously highlighted by the European Parliament in an extensive study on legal pathways and humanitarian visas. The study notes that a reduction of irregular migration to the EU could be achieved, with potential to reduce the costs associated with surveillance and border management and search and rescue operations, which would stem from asylum seekers being able to substitute more dangerous options with safer ones, i.e., humanitarian visas (EPRS, 2018).

Humanitarian VISAs and Human Rights obligations

There are two cornerstone legal documents that set the human rights obligations of the European Union, the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) and the subsequent Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (CFR or Charter). According to the Articles 2 & 6 of the TEU, the fundamental rights that they establish should be considered primary law, therefore all Union Law is governed by them including the Common European Asylum Policy (CEAS) and the Community Code on Visas (CCV or Visa Code). Αrticles 3 ECHR and 4 CFR enshrine the principle of non-refoulement, that people seeking protection cannot be denied if it would put them on risk of persecution. At present, there are no explicit humanitarian provisions on the Visa Code.

They are only mentioned as exceptions in Articles 19 and 25 CCV, which the European Court of Justice rule to be too at the discretion of member-states in X and X[1]. The Visa Handbook requires applications to be assessed in terms of how likely the applicant is to return to their country at the expiration of the Visa, even though an asylum seeker by definition, would be the least likely person to return to their country (Morelo-Lax, 2018). In an ideal scenario, a reform of the Visa Code would take place. However, we acknowledge that it is unrealistic to expect in the current political environment an expansion of the CCV and therefore our proposal would also work through the Article 19 exceptions.

National Practices on Humanitarian Visas

“…at least 16 member states have used some form of humanitarian visas in the past. Greece is not one of these countries.”

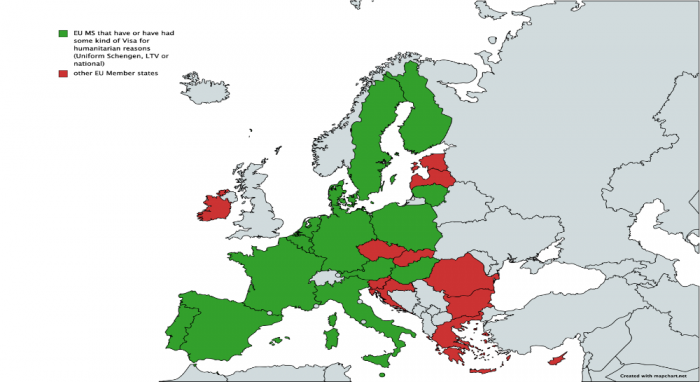

European Union member-states have historically used schemes that are similar to the Humanitarian Visa system proposed in this paper, and some Member States still issue such visas. According to a study by the European Parliament (Jensen, 2014) at least 16 member states have used some form of humanitarian visas in the past. Greece is not one of these countries. That number has significantly reduced since 2015 (EPRS, 2018). The map below shows the geographical spread of these practices.

Source: Jensen, 2014

According to the official statistics by the European Commission, in 2019 there were 15,022,255 uniform Schengen Visas issued compared to just 129,176 LTV visas. Thus, only approximately 0.85% of visas issued that year were Limited Territorial Validity (LTV) Visas[2], with the numbers from previous years following very similar patterns. Although there are no official numbers on how many of the LTV Visas were issued for humanitarian reasons, studies have shown (EPRS, 2018) that humanitarian visas would be included in these numbers, alongside the reasons of national interest also outlined in the Visa Code.

“…although the use of Limited Territorial Validity (LTV) visas for humanitarian reasons is considerably widespread geographically, it is actually used in very limited circumstances.”

This data shows that although the use of LTV visas for humanitarian reasons is considerably widespread geographically, it is actually used in very limited circumstances. These visas are most often issued at the discretion of either the specific consulates where the application was lodged or due to instructions given via directives from the government to the consulates for very narrow circumstances. Due to the legally “exceptional” status of these VISAS, they are issued only on a discretionary case-by-case basis without the necessity of a uniform set of standard or the possibility of an appeal (Noll et al., 2002) National governments have chosen to enable such a pathway to asylum on an ad-hoc basis according to their own will and interests and these programmes tend to be very narrowly tailored geographically and in terms of duration.

In most cases, such as the case of France and Italy, humanitarian visas are used in a targeted manner to essentially create a humanitarian corridor between the country of origin and the country offering the programme. Italy, for example, following a bilateral agreement with Libya, allowed 150 Eritreans to travel from Libya by issuing LTV visas (Noll et al., 2002). France uses LTV visas more extensively for humanitarian purposes. Consulates may issue a special visa for arriving in France to claim asylum in the form of 6-month LTV Visas (Office français de protection des réfugiés et apatrides). However, this is used in very narrow circumstances at the discretion of the government which empowers the consulates to issue them. Thus, in 2013, France issued 791 such Visas to Syrians and in 2014 there were 1,295 issued to Iraqi Christians (Huegen, 2014). Crucially, in both these countries’ cases, humanitarian visas were not inscribed in national law. The programmes’ activation, duration and scope were fully discretionary through government directions.

Overall, different types of humanitarian visas have been used and are currently being used across the European Union. However, they are issued in very limited numbers and for the most exceptional circumstances. They are very rarely formalised in national law, instead their use is determined by political decisions and is often targeted towards specific nationalities according to the foreign policy interests of the issuing country. Decisions on applications are very difficult -if not impossible- to be appealed and a high degree of discretion is used in assessing individual cases.

The lack of a uniform European policy on humanitarian visas creates a chicken-and-egg situation that necessarily limits the use of such visas, beyond the legal restrictions of the Visa Code. Should a single member state have a functional and formalised system of humanitarian visas, they would become overwhelmed with applications and thus reluctant to pursue such policies. However, without a wide use of humanitarian visas on a national level it becomes harder to pursue such a policy at the European level as it remains largely untested beyond limited and discretionary use.

What could a humanitarian visa scheme look like?

As has been discussed above, the current legal framework of the European Union does not allow for a coordinated regime of humanitarian visas. The court case of X and X especially highlighted the need for new European Legislation for their establishment because it ruled that there is no requirement under current EU Law to issue them. A humanitarian visa would address both concerns. It should be noted that ideally, from an EU-constitutional perspective, this would take place through an amendment of the Community Visa Code (CCV). However, due to the post-2015 political context regarding refugees and the fat that EU states do not share positive recognition of refugee status, such an approach would lead to the breakdown of the Schengen system itself. The proposal focuses more on how the system would function to demonstrate how it could be an alternative humanitarian solution for limited numbers and the most exceptional circumstances.

“…the current legal framework of the European Union does not allow for a coordinated regime of humanitarian visas.”

Humanitarian visas would resemble Limited-Territorial Validity Visas. A parallel system could emerge that would take advantage of the ‘exceptional circumstances’ clause in Article 19(4) of the CCV. The requirements for issuing such a visa would be common across the European Union. In addition, guidelines for their interpretation would be published for all member-states to follow. The application would take place in consulates of EU member states in the countries of origin and transit, at least initially. We acknowledge that this would automatically limit access for those in conflict zones or remote areas and it would be worth reflecting whether special roaming offices could be set in partnership with UNHCR. For those already in the country of origin and transit with access to consulates the process would consist of these steps:

- Prospective asylum seekers would be able to apply for these visas at any foreign representation of an EU member state. Since EU member states do not share positive recognition of asylum claims, it would be impossible to have one member state process an application on behalf of another. Yet, EU consulates can function as initial points of contact between applicant and member state. The application would be forwarded to the respective member state’s asylum service or designated actor.

- The consulate would then conduct their own pre-screening which should take place within a fixed period of time that balances security considerations (such as cross-referencing the EU’s recently proposed counter-terrorism database) while taking into account the urgency of each particular situation. Once this is completed, it would initiate a process in which the candidate is invited to an interview, either in-person or online.

- Following the interview, a successful candidate would be given their visa for that member state and would generally be responsible for their own traveling arrangements. The consulates could establish a travel-sponsorship fund in cooperation with NGOs, and private sponsors (e.g. family members) for the successful applicants that they are demonstrably not able to do so.

- The applicant would be under the humanitarian visa status until the asylum process concludes, upon which he/she would receive international protection. This means that those who would qualify would need to meet certain criteria evident during pre-screening. In practice, the process would function as a quicker way of getting people to safety. In addition, it would allow the beneficiary to be able to work at the destination country so that it is a more attractive option for those who qualify to avoid undertaking an irregular journey. As with the LTV Visas, it would only allow for staying within the issuing nation’s borders for the duration of the application process.

- A full right to appeal is also necessary for the process to be fully compatible with human rights requirements.

“In principle, rejection should be rare since meeting the criteria for issuing the humanitarian visa implies pre-recognition of one’s need for protection.”

Additionally, a successful application for a humanitarian visa would be considered as an element in favour of the applicant in their eventual asylum application. In principle, rejection should be rare since meeting the criteria for issuing the humanitarian visa implies pre-recognition of one’s need for protection. This detail is important as it would act as an incentive for the prospective refugee to go through the humanitarian visa process rather than attempting to irregularly enter the territory of an EU member state to lodge their application. Having said that, a previous denial of a humanitarian visa cannot preclude one from lodging an application for asylum should they find themselves inside EU territory. If that were the case, it would effectively be an extraterritorial assessment of a candidate’s international protection potential, which experts believe raises serious human rights concerns (McAdam, 2015). This is also the same reason why it is necessary to have humanitarian visas in the first place, rather than granting full refugee status at the consulates.

The primary incentive for participation could be EU-Commission funds that would support the implementation cost of the additional infrastructure required at consulates. In addition, participation in this scheme could act as a counterbalance to reduced participation in intra-EU refugee relocation schemes, though this would require a minimum number of visas are issued to guarantee the system is not abused by member states.

The aforementioned system, is not a one-size-fits-all, and the speedy examination of applications presupposes the establishment of a hierarchy of criteria as to who can apply for a visa for EU entry, while ensuring that Member States comply with their humanitarian obligations and respect of fundamental rights. Priority can be given to vulnerable groups (unaccompanied children, women, elderly, people with health condition) but also to categories (eg based on nationality due to developments in a country) formed in cooperation with the UN High Commissioner for Refugees. Individuals who have previously participated in a return program and/or rejected asylum seekers, could be de-prioritized and would not be able to apply for the humanitarian visa scheme.

Conclusion

As mentioned above, in the ideal scenario Humanitarian visas of the form articulated in this proposal and similar proposals submitted before by the European Parliament would result in a complete transformation in the ways that asylum seekers enter the European Union.

In order to be able to plan for and implement any significant reform towards a common humanitarian visa regime for asylum applicants, there needs to be rigorous discussion between Member States, and an agreement is far from certain. It’s worth remembering that the European Parliament has for years tabled suggestions for alternative legal pathways to the EU as have lawyers and academics working in the field of asylum. The current paper utilizes many of the arguments and suggestions put forth in the past with the aim of reintroducing the issue and restarting the conversation.

“The European Union is one of the most prosperous regions globally and yet as things currently stand, prioritization of deterrence and strict Schengen rules have made it an impenetrable “Fortress Europe”.”

The European Union is one of the most prosperous regions globally and yet as things currently stand, prioritization of deterrence and strict Schengen rules have made it an impenetrable “Fortress Europe”, with practically no formal pathways for asylum seekers to enter. Establishing legal avenues for those who seek to apply for asylum, even if it only applies to specific categories, would allow for a widening of the ‘gates of the fortress’, while offering substantial benefits to member states.

[1] The Court ruled that the issuing of LTV Visas falls solely on national law because there is no explicit provision regarding how they should be issued in the visa code. However, that decision does not negate the human-rights and international obligations concerns regarding PEPs, but rather shows precisely the need for new legislation to address them.

[2] Limited Territorial Visas (LTVs) allow the owner to stay within only the issuing nation state whereas a full Schengen Visa allows for free movement throughout the Schengen Zone.

Bibliography

Connor, P. (2016) ‘Illegal migration to EU rises for routes both well-worn and less travelled’. Pew Research Centre.

European Parliament. (2016). The Situation in the Mediterranean and the Need for a holistic EU approach to Immigration. Brussels: Resolution 2015/2095.

European Parliamentary Research Service. (2018). Humanitarian Visas: European added Value Assessment accompanying the European Parliament’s legislative own-initiative report. Brussels : European Parliament.

Huegen,P (Apr. 17, 2014), Réfugiés syriens: leur nombre en constante augmentation en Occident [Syrian Refugees: Their Numbers in Constant Increase in the West], RFI

Jensen, U. I. (2014). Humanitarian Visas: Option or Obligation? Brussels: European Parliament.

Maldini P & Takahashi, M. (2017) Refugee Crisis and the European Union: Do the failed migration and asylum policies indicate a political and structural crisis of European Integration, Communication Management Review 2:2 (54-72)

McAdam, J .(2015). Extraterritorial processing in Europe Is ‘regional protection’ the answer, and if not, what is? Perth: Kaldor Centre for International Law

Moreno-Lax, V. (2018). The added Value of EU Legislation on Humanitarian Visas- Legal Aspects. Brussels: European Parliament.

Noll, G., Fagerlund, J., & Liebaut, F. (2002). Study on the feasibility of processing asylum claims outside the EU against the background of the common European asylum system and the goal of a common asylum procedure. Copenhagen: The Danish Centre for Human Rights.