This policy paper presents some first findings from a youth survey relating to the skills mismatch in Greece. The survey was conducted in the context of the EEA Grants sponsored research project “Youth employment and gender equality: Mobilizing human capital for sustainable growth in Greece”, which is implemented by ELIAMEP and the Norwegian institute Fafo. The project seeks to document and analyze conditions in the Greek labour market, with an emphasis on the main barriers constraining young people’s access to it and on their progress once they get a job. Pending a more in-depth analysis of the findings, the preliminary evidence presented here adds some insights to the study of the skills mismatch phenomenon in Greece and helps us outline a few policy proposals.

- Skills mismatch is a significant problem for modern economies, as it leads to the inefficient utilization of the labour force, reducing productivity and growth potential.

- Research shows that Greece faces a serious skills mismatch problem.

- The findings of a youth survey presented here:

- Confirm the problem for the Greek labour market in both its vertical (over/ underqualification) and horizontal (field of study) dimensions.

- Show that skills mismatch affects graduates within every level and orientation (e.g., vocational training) of the educational system.

- Document young people’s belief that the educational system does not prepare them well for the labour market

- Show that skills mismatch is a serious obstacle to labour market entry for young people

- Confirm the lack of learning opportunities for those in employment, as well as the importance which young people attach to such opportunities for their professional progress.

- Reveal that young people often reject jobs due to low pay and unsatisfactory employment conditions, implying that reported skills shortages are also due to the terms of employment on offer.

- Policy responses should be multi-faceted, targeting both the educational system and the economy.

- Providing students with information about market developments and trends, and taking such information into account in the design of educational curricula (particularly in vocational training) is essential if the skills mismatch problem is to be addressed.

You may read here in pdf the Policy Paper by Dimitris Katsikas, “Stavros Costopoulos” Senior Research Fellow; Head, Greek & European Economy Observatory, ELIAMEP.

Introduction

“…the impact of mega-trends like globalization and demographic decline, digitalization and the green transition, have put pressure on all EU member states to adjust their economies. These developments have created the need for new skillsets and for educational re-orientation in novel directions.”

In a broad sense, the term ‘skills mismatch’ refers to the incongruity between workers’ qualifications and the requirements of the jobs and vacancies available in the labour market. The concept has attracted a lot of attention in recent years, particularly in Europe. This increased interest is to some degree related to the effects of the economic crisis of the previous decade, as a result of which an increased share of the labour force faced difficulties finding a job that corresponded to their educational credentials and/ or their skills. Over and above the effects of the crisis, the impact of mega-trends like globalization and demographic decline, digitalization and the green transition, have put pressure on all EU member states to adjust their economies. These developments have created the need for new skillsets and for educational re-orientation in novel directions.

“The effects of the crisis notwithstanding, the skills mismatch problem in Greece seems to be rooted in deeper, structural weaknesses in both the Greek economy and educational system.”

The skills mismatch in Greece is considered extensive, with the country typically occupying the last places among EU member states in various relevant rankings (e.g., Cedefop 2019, 2020a; OECD 2019). The economic crisis made things worse, as highly educated and/or skilled people found themselves unable to find suitable jobs; this, in conjunction with a substantial increase in overqualification (SEV 2019), led to ‘brain drain’ and ‘brain waste’ phenomena, as large numbers of workers either left the country or became long-term unemployed or under-employed. The effects of the crisis notwithstanding, the skills mismatch problem in Greece seems to be rooted in deeper, structural weaknesses in both the Greek economy and educational system; given the aforementioned challenges, which are particularly pressing for Greece, this is a cause for significant concern.

This policy paper presents some first findings from a youth survey relating to the skills mismatch in Greece. The survey was conducted in the context of the EEA Grants sponsored research project “Youth employment and gender equality: Mobilizing human capital for sustainable growth in Greece”, which is implemented by ELIAMEP and the Norwegian institute Fafo. The project seeks to document and analyze conditions in the Greek labour market, with an emphasis on the main barriers constraining young people’s access to it and on their progress once they get a job. Pending a more in-depth analysis of the findings, the preliminary evidence presented here adds some insights to the study of the skills mismatch phenomenon in Greece and helps us outline a few policy proposals.

The concept of skills mismatch

The concept of skills mismatch is often used in public discourse in a generic way, implicitly referring, most of the time, to the phenomenon of overqualification; conversely, it is sometimes invoked in the discussion on skill shortages in the economy. However, these two phenomena are different and pose different economic and policy challenges. In fact, skills mismatch is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, and in order to formulate appropriate policy proposals, we need to delineate its various dimensions.[i]

First, there is the so-called vertical dimension, which measures over- and under-qualification. Here, the level of a worker’s qualifications is measured against that required for their job to determine whether they have more qualifications than needed (overqualification, or human capital surplus), or fewer (underqualification, or human capital deficit). Skills mismatch also has a horizontal dimension, which refers not to the level of educational attainment and/or skills of the workers, but rather to their substance (e.g., field of study), and its lack of relevance to the object of their work. Finally, skills obsolescence can also be thought of as a form of skills mismatch, whereby workers’ skills become less relevant to the performance of their job over time for reasons such as technological change, or changes in market conditions. These types of skills mismatches relate more to the supply side of the labour market, i.e., they mainly refer to the characteristics of the labour offered by workers and the degree to which these correspond to existing labour positions and vacancies.

There are also aspects of the skills mismatch phenomenon which can be analysed from the demand side of the labour market: i.e., the companies that employ or seek to employ workers. Here we encounter skills gaps and shortages. The former refers to situations where workers do not have the necessary skills to perform their duties competently, while the latter to the inability of employers to find suitably qualified workers for vacancies they need to fill.

“Skills mismatch is generally considered as a problem for both workers and companies, being related to negative wage differentials and lower job satisfaction for the former, and increased costs and reduced productivity for the latter.”

Skills mismatch is generally considered as a problem for both workers and companies, being related to negative wage differentials and lower job satisfaction for the former, and increased costs and reduced productivity for the latter. At the macroeconomic level, the inefficient use of human capital leads to a loss in competitiveness and reduced growth potential. These adverse dynamics do not always hold; during a period of strong economic growth, for example, skills shortages can be expected and can even be taken as a sign of the economy’s dynamism (Vandeplas and Thum-Thysen 2019); in other cases, at an individual level, vertical or horizontal mismatch may relate to personal preferences or timing considerations in individual career paths. Overall, however, and when skills mismatch phenomena are long-term structural features of an economy, there is little doubt that they adversely affect productivity and economic growth.

There are many theoretical and methodological issues with the definition and measurement of the various aspects of skills mismatch, which cannot be discussed in this short policy paper. One such issue is the distinction between over/under-education and over/under-skilling. The former concept is more theoretically challenged, in the sense that for many people there can be no such thing as over-education. Moreover, many experts have argued that the possession/lack of skills is more relevant than the educational level for assessing job performance, while empirical studies have shown that the effects of over/under-skilling tend to be more consistent and severe than those of under/over education.

Part of the methodological debate has to do with the tools employed to measure skills mismatch. One of the tools most used for gauging skills mismatch is a survey of workers or employers. Such surveys are an extremely useful methodological tool which allow us to take a deeper look at the occurrence and dynamics of skills mismatch; however, surveys also have their weaknesses, most of which relate to the personal bias inherent in the respondents’ answers. The survey presented here follows this tradition of the so-called ‘subjective method’; it offers significant insights into the experience and perceptions of young workers and jobseekers, which however, have to be evaluated in the light of the results of other, empirical analyses which draw on more ‘objective’ datasets, such as occupational and educational attainment registries.

Skills mismatch in Greece

“According to the European Skills Index (ESI) developed by Cedefop, Greece’s skills system performs very poorly.”

According to the European Skills Index (ESI) developed by Cedefop, Greece’s skills system performs very poorly. According to Cedefop (2020a, p.4), “The skills system’s role is to ensure, as far as is feasible, that skills demand is met by skills supply in a way that optimizes the use of the skills available in the labour force.” To determine a skills system’s capacity to achieve this objective, the ESI index is composed of three sub-indices: skills development (which measures the development of skills through the educational, vocational training, and life-long learning systems), skills activation (which measures the participation of different skills in the labour market), and skills matching (which measures the effective matching of available skills with those required in the labour market).

Greece ranks very low on every index. In the overall index, Greece comes second from bottom, above only Italy, with a score of 30, while the leader (the Czech Republic) has a score of 77 (the perfect score being 100). Despite this, Greece’s performance has improved somewhat in relation to previous measurements: it scored just 23 in 2016, when it was in joint last place with Spain, which had the same score. In terms of the sub-indices, Greece scored 43 in skills development, ranking 5th from bottom, 45 in skills activation, ranking 4th from bottom, and 17 in skills matching, ranking last, as it did in previous measurements, although it has improved its score from the extremely low score of 9 which it achieved in 2016.

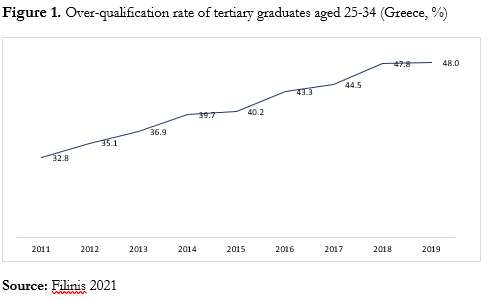

“Looking more closely at the skills matching dimension in Greece, it becomes clear that the country faces a serious over-qualification problem, particularly among young tertiary education graduates, which has become worse over time.”

Looking more closely at the skills matching dimension in Greece, it becomes clear that the country faces a serious over-qualification problem, particularly among young tertiary education graduates, which has become worse over time (Figure 1).[ii] The deterioration in the index relates to the crisis and the nature of the recovery in recent years; given the structural features of the Greek economy, most of the recovery, in terms of employment, has been in low skills, low value-added sectors such as retail, tourism services, and the food and drink industry. It is telling that the top sector in terms of youth employment in 2019 was the “Retail trade”, which increased its share still further to 16.2% compared to 14.1% in 2008, while “Food and beverage service activities” rose to second place, doubling its share compared to 2008 (14.7% vs. 7.3%) (Filinis 2021). The incidence of overqualification in these sectors is very high and has increased substantially since the crisis, making them the largest contributors of overqualified employment positions in the economy (SEV 2019).[iii] The combination of high youth unemployment and extensive overqualification can also lead over time to the obsolescence of the qualifications and skills acquired by young people, trapping some of them in low-skill, low-pay jobs; that would mean that the investment made in their education was wasted, and would reduce the growth potential of the economy.

Matching jobs with fields of study is also sub-optimal in the Greek labour market. The horizontal mismatch is estimated at over 30%, with “Agriculture and Veterinary” studies facing a particularly acute problem (73% of the graduates in this field work in unrelated professions), while the fields of “Humanities, Languages and Arts”, “Science, Mathematics and Computing” and “Engineering, Manufacturing and Construction” also face severe problems (over 40%, and in the case of humanities over 50%, work in unrelated professions) (KANEP-GSEE 2019). Despite their poor professional prospects, some of these fields of study remain very popular with Greek students.

“On the labour demand side, skill shortages are also consistently high in Greece.”

On the labour demand side, skill shortages are also consistently high in Greece. According to the latest talent shortage survey conducted by Manpower, 80% of employers are facing difficulties finding the appropriate personnel (Manpower 2021). This is an all-time high for Greece, and the results have undoubtedly been affected by the pandemic, as evidenced by the fact that the percentage of difficulties reported has spiked globally. Nonetheless, Greek employers ranked very high in terms of reported hiring difficulties even before the pandemic, a situation which was also confirmed by a recent domestic survey conducted by the SEV (2019).

“…skills shortages may relate to the wage and employment conditions offered by companies.”

The skills shortages problem should not, however, be attributed entirely to the labour supply. As McGuiness et al. (2018) note, skills shortages may relate to the wage and employment conditions offered by companies. It is no secret that the wages Greek companies have offered since the crisis have not been particularly attractive on average, while other aspects of the employment on offer, such as training opportunities, are also in short supply in Greece; only 21.7% of Greek enterprises offer continuing vocational education and training (CVET), compared to 72.6% in the EU (Cedefop 2020b).

The survey findings

The survey was carried out on a sample of 650 people, aged 15 to 34, using the technique of simple random sampling; its geographical coverage encompassed the entire Greek state. In order to collect the sample, quotas of gender, age group (4 sub-categories: 15-19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34 years old), geographical region (13 administrative regions), and the urban/rural dimension (5 categories: rural, semi-urban, urban, large urban, urban agglomeration of Athens and Thessaloniki) were observed. It has to be stressed that the presentation that follows is exhaustive in neither scope nor depth; it is a first presentation of findings related to the youth skills mismatch in Greece.

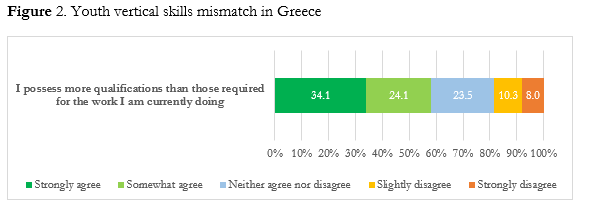

“…close to 60% (58.2%) of the respondents believe that they possess more qualifications than those necessary for their work.”

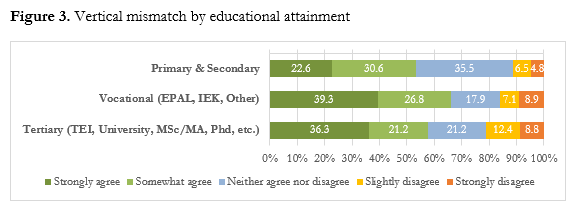

We start with a question that speaks directly to the vertical dimension of skills mismatch (Figure 2). We see that close to 60% (58.2%) of the respondents believe that they possess more qualifications than those necessary for their work. An analysis based on educational attainment (Figure 3), shows that, as expected, low educational credentials (primary & secondary) are associated with fewer mismatch perceptions, particularly for those who seem to be more certain in their assessments (“strongly agree”). On the other hand, given their lack of specialized knowledge, the overall percentage of respondents in this category who report a vertical skills mismatch (53.2%) seems surprisingly large. This result could be explained to some degree by the personal bias argument (people overestimate their qualifications), but it could also reflect the fact that the jobs young people secure have such low requirements that even workers with compulsory or secondary-level qualifications feel overqualified. The answers provided by respondents with vocational education and training (VET) are also surprising, as they seem to report a mismatch more often than those with tertiary education qualifications (66.2% vs. 57.5%).[iv] Notable differences are also observed between rural and urban areas (48.6% in the former vs. more than 60% in all urban areas, with the exception of Athens and Thessaloniki, where the figure was somewhat lower at 56.5%) and in the private (61.7%) compared to the public sector (42.5%).

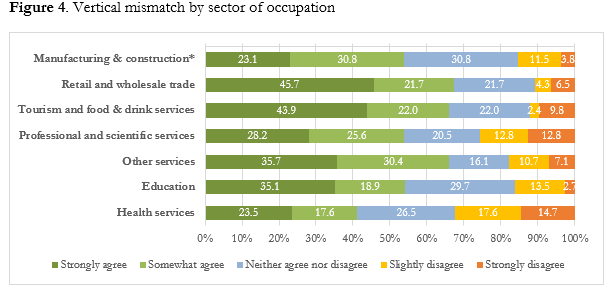

“…respondents employed in the retail and wholesale trade, and in tourism and food and drink services, report the highest rate of vertical mismatch.”

Finally, looking at the sectors where the respondents are employed (Figure 4), we see that, as expected, respondents employed in the retail and wholesale trade, and in tourism and food and drink services, report the highest rate of vertical mismatch, along with “other services” (transport services and logistics, information technology and telecommunications, and finance and insurance services). This contrasts with those employed in manufacturing and construction, who report low levels of mismatch (23.1% is the lowest percentage of “strongly agree” responses).

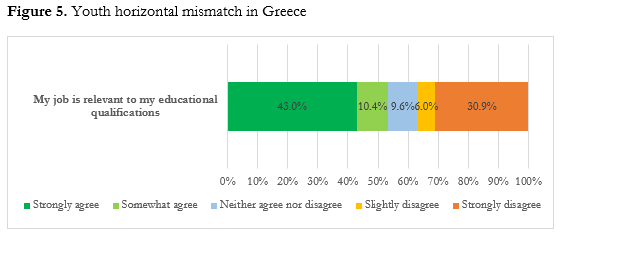

In terms of horizontal mismatch, things appear to be better, though still far from good (Figure 5);[v] 36.9% of the respondents replied that their educational qualifications are not relevant to their jobs. Sifting through the data, we see that notable differences are observed between the big urban areas (Athens, Thessaloniki, and other major cities) and smaller urban areas, with the former exhibiting lower percentages of reported mismatches than the latter. In addition, atypical forms of employment (part-time/seasonal) are associated with a higher incidence of horizontal mismatch (53.1%) than full-time employment (34.6%).

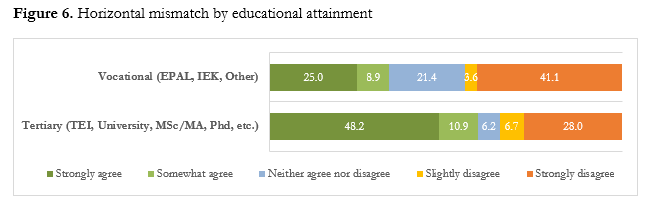

“…vocational training graduates report a higher incidence of horizontal mismatch compared to tertiary education graduates. Given their specialized training, this finding is rather surprising.”

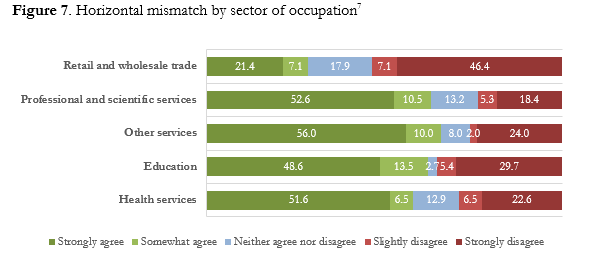

Disaggregation in terms of educational attainment (Figure 6) shows that, as with vertical mismatch, vocational training graduates report a higher incidence of horizontal mismatch compared to tertiary education graduates. Given their specialized training, this finding is rather surprising and points to a mismatch between the curricula of professional training programmes in Greece (which are developed with little input from the employers’ side) and the needs of the economy. Finally, an analysis per sector of employment (Figure 7) reveals that, once again, respondents employed in the retail and wholesale trade report considerably higher rates of horizontal mismatch.[vi]

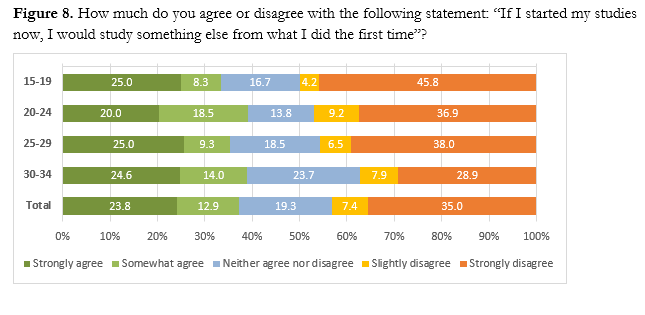

“…we asked them whether they would choose a different field of study if they could start all over again. More than one in three respondents (36.7%) answered positively.”

In an attempt to obtain the respondents’ overall impressions based on their experience to date, we asked them whether they would choose a different field of study if they could start all over again. More than one in three respondents (36.7%) answered positively (Figure 8). It is interesting to note that for the older age group (30-34), who have several years of work experience, the percentage of positive answers (38.6%) is higher than the overall average. Of course, this answer is not necessarily the result of a negative mismatch experience; it could also indicate a re-evaluation based on knowledge acquired about more promising professional avenues than the one chosen. Still, this finding, combined with the fact that one in three respondents in the 15-19 age group, who do not yet have extensive work experience, also answer positively, implies a problem with the way young people make their educational and career choices and it indicates an obvious failure on the part of the current educational/professional orientation services.

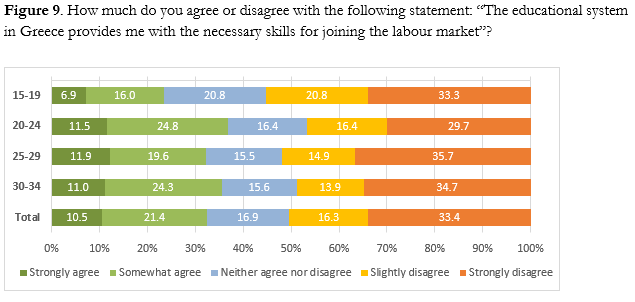

To gauge the participants’ views on the educational system more directly, we asked them whether they thought it had provided them with the skills they needed to join the labour market (Figure 9).

“…half of the respondents (49.7%) do not believe that the educational system provides them with the skills they need.”

Fewer than one in three respondents (31.9%) replied positively. Although, as evidenced by the better evaluation of the three older age groups compared to the 15-19 group, people tend to have a more positive assessment of the educational system after they have worked for a few years, the numbers are still very low, hovering around the one-out-of-three mark. Even if we exclude those who are uncertain, half of the respondents (49.7%) do not believe that the educational system provides them with the skills they need, which clearly demonstrates a failure to connect the educational system to the labour market.

A final note on skills obsolescence. In an effort to acquire an overall impression of the difficulties faced by young people in their pursuit of a career in Greece, we asked them how long it had taken them to find a job related to the career they wanted to pursue, and in which year they found that job. The responses show that almost one in four (23%) of the respondents who have sought such a job have still not found it. For the people who found a job related to the career they wanted to pursue after 2015 (60% of the total), 28.3% reported that it took them more than two years to do so. It is evident that young people are having trouble finding jobs that match their aspirations (and therefore presumably their qualifications), and we know that the longer it takes someone to find such a job, the more obsolete their qualifications and skills become.

Up to now, the questions reviewed relate to young people’s work experience. However, skills mismatch is not only a problem for those who are already working. When asked to evaluate the principal obstacles they face when trying to enter the labour market, the respondents assigned vertical mismatch (underqualification in this instance) and horizontal mismatch a score above 3 (on a 5-point scale), ranking below only lack of experience and the state of the economy (during the pandemic, too).

Finally, although our survey deals by definition with the supply side of the labour market (which is to say its questions are addressed to current and potential workers), it also yields findings which are of interest in relation to the demand side of the labour market (i.e., employers) regarding the skills mismatch issue. Thus, for example, workers consider the lack of learning opportunities to be a significant impediment to their professional progress. Respondents were asked to evaluate the factors that have held their careers back to date, and the “lack of learning opportunities in the jobs I had so far” scored above 3 (on a 5-point scale), ranking as third most important factor, above the “lack of the type of qualifications/ skills required for advancement”.

“Almost half of the respondents (46.7%) stated that they had rejected or not considered a job post over the last four years.”

This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that hiring difficulties may relate to the terms offered by employers and to the prospects job applicants associate with a particular post. A more direct examination of this argument was made through another set of questions, which investigated the jobs which respondents rejected. Almost half of the respondents (46.7%) stated that they had rejected or not considered a job post over the last four years. Given the high level of youth unemployment in Greece, this percentage is surprisingly high and implies that the employment terms offered do not meet the candidates’ needs. Indeed, when asked to give the reasons for their decision, low-pay and terms of employment (e.g., working hours, conditions of work) topped the list, while relevance to qualifications/skills was also given as a reason by 8.6% of the respondents.

Conclusions and policy implications

Skills mismatch is a significant problem for modern economies as it leads to the inefficient utilization of the labour force, reducing productivity and growth potential. The impact of the pandemic and the major challenges of the future add urgency to the efforts to address it. For Greece, which is burdened by long-term structural weaknesses in its growth regime and the legacy of a decade-long crisis, the need to employ its human capital efficiently is even more pressing.

“The findings presented in this policy paper confirm the magnitude of the skills mismatch problem in Greece.”

The findings presented in this policy paper confirm the magnitude of the skills mismatch problem in Greece. Respondents report instances of both vertical and horizontal skills mismatch at a very high rate. Surprisingly and unfortunately, these percentages are not substantially affected by either the level or the type of educational attainment, even when it comes to vocational training graduates, who are supposed to receive trade-specific training. From the responses our questions received, it is obvious that young people do not believe that the Greek educational system does a good job preparing them for the labour market, or even informing them about different career options and prospects.

“…the dominance of low-skill, low-pay jobs in the Greek economy, particularly for young people, magnifies the skills mismatch problem.”

On the other hand, the dominance of low-skill, low-pay jobs in the Greek economy, particularly for young people, magnifies the skills mismatch problem, as the share of youth employment in such occupations has risen in recent years, reflecting the unsatisfactory nature of the post-crisis recovery in both economic and social terms. This is also reflected in the high percentage of respondents who have rejected a job in recent years. Moreover, the reported lack of learning and skill-upgrading opportunities demonstrates structural problems in the Greek economy, such as the predominance of low value-added activities and the very small size and unprofessional management of most Greek companies.

Combined, these factors lead to disappointment and low participation rates among young people, who compromise and settle for low-skill, low-pay jobs, as well as to skills obsolesce and a brain drain, all of which impact adversely both on workers’ quality of life and the growth potential of the Greek economy.

A comprehensive and detailed set of policy proposals for addressing the skills mismatch problem in Greece cannot be presented here; such an exercise would necessitate a deeper and broader analysis of the problem, along with an evaluation of the relevant institutional and policy framework. However, based on the findings presented above, certain policy implications are evident.

“…having highly skilled graduates will not solve the problem, if there are no companies to make use of their skills.”

First, a multi-faceted policy response is required to a multi-faceted problem. There is no doubt that there are skills shortages in Greece, which need to be addressed by promoting the development of skills in the educational system (for example, through dedicated courses and through teaching methods that encourage learning through the development of key skills such as problem-solving, teamwork and critical reasoning). However, having highly skilled graduates will not solve the problem, if there are no companies to make use of their skills; addressing only the supply side of the problem would actually lead to even higher rates of overqualification and, probably, to brain drain. The transition to a more extroverted, innovative and competitive economy is essential if the skills of the workforce are to utilized efficiently and further developed, but also to enable employers to compensate them with satisfactory wages. Over and beyond much-needed broad economic reforms (e.g., in product markets), the policy armoury should also include incentives and financing allowing small and medium-sized companies and start-ups, in particular, to invest in their human resources, through continuous learning and other schemes.

Regarding the educational system, the findings of the survey point to what appears to be a mismatch between the VET curriculum and the needs of the economy, a finding that is corroborated by other research (Lalioti 2021). This is particularly disappointing, given that this part of the educational system is supposed to be most attuned to the market. There is an urgent need to remedy this gap, particularly if Greece wants to increase the proportion of VET graduates in the Greek labour market.

“…the findings presented here demonstrate an urgent need to develop a forward-looking educational- and professional-orientation and counselling system.”

Finally, in terms of the connection between the educational system and the market, the findings presented here demonstrate an urgent need to develop a forward-looking educational- and professional-orientation and counselling system, particularly for secondary and compulsory education students. Students need to be provided with up-to-date information about their educational and career options by experts (rather than unqualified and uninterested teaching staff), so they can make informed decisions about their future. Similar guidance should be made available to students in post-secondary and tertiary education about the next steps in their educational and career paths.

In recent years, several reforms have been promoted in education, including the VET system, while valuable new tools have been developed including the “Mechanism for diagnosis of labour market needs” developed in recent years by Greek governments in cooperation with social partners and with the support of Cedefop. Unfortunately, until now at least, these initiatives have been unable to establish a real-time, forward-looking connection between the job market, on the one hand, and the design of the VET curriculum and the professional-orientation services provided within the broader educational system (including tertiary education), on the other.

These suggestions and others like them fall under the purview of the NextGenerationEU Recovery and Resilience Fund, and can be funded by the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP). As is also the case in relation to other facets of the Greek economy, the NRRP constitutes a unique opportunity to combine ambitious reforms with the funding required to implement them successfully; it should not be wasted.

[i] The categorization presented here follows McGuinness et al. (2018).

[ii] A comprehensive analysis of the problem would need to look at the other two dimensions, too, where serious problems are also encountered (e.g., the low level of particular skills (like problem solving), despite high educational attainment, and the low penetration of vocational training in the area of skills development, and weaknesses in the transition from education to the labour market in the area of skills activation).

[iii] To be precise, the top contributors are “Wholesale and Retail Trade-Repair of Motor Vehicles and Motorcycles (45-47)”, and “Accommodation and catering service activities (55-56)” (SEV 2019).

[iv] In our survey, there are 10 different educational attainment categories; for analysis and presentation purposes, data are often grouped in broader categories due to the small sample size in the individual categories.

[v] The data presented refer only to vocational and tertiary education graduates, as primary and secondary education graduates do not have a field specialization.

[vi] The food and drink industry is not presented here; due to the extraction of primary and secondary graduates from the sample in the questions on horizontal mismatch, the number of respondents in this category is too low.

[vii] The asterisk in “Manufacturing and construction” signifies that the sample size for this category is small, compared to the threshold for the other categories.

References

Γούλας, Χ., Ζάγκος, Χ. και Ν. Παΐζης (2019) «Δεξιότητες, εκπαίδευση και απασχόληση: Εκπαιδευτικοί δείκτες και εργατικό δυναμικό», ΚΠ-01, ΚΑΝΕΠ-ΓΣΕΕ, Αθήνα.

ΣΕΒ (2019) Special Report: Αναντιστοιχία προσόντων.

Cedefop (2020a) 2020 European Skills Index Technical report.

Cedefop (2020b) Strengthening skills anticipation and matching in Greece: labour market diagnosis mechanism: a compass for skills policies and growth. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Cedefop (2019). 2018 European skills index. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Cedefop reference series; No 111.

Filinis (2021). Young people in the Greek labour market, unpublished manuscript.

Lalioti (2021) Vocational Education and Training (VET) in Greece, unpublished manuscript.

ManpowerGroup (2021) Press Release: ManpowerGroup Employment Outlook Survey Q3 2021, Athens, Greece, June 8.

McGuinness, S., Pouliakas, K. and Redmond, P. (2018) “Skills Mismatch: Concepts, Measurement and Policy Approaches”, Journal of Economic Surveys, 32: 985-1015.

OECD (2019) “Skills Strategy: Greece”, May.

Vandeplas, A. and A. Thum-Thysen (2019) “Skills Mismatch & Productivity in the EU”, European Economy Discussion Paper 100, DG ECFIN, European Commission.