Although disruption remains the norm in Turkey’s behavior, the EU should stand firm in developing a strategy of “balancing engagement” to keep Turkey anchored in the broader European and transatlantic framework. The Customs Union is an important instrument at the EU’s disposal for concluding an agreement with Turkey and negotiations can lead to an agreement that would balance European and Turkish interests. Moreover, a European strategy towards Turkey should address not only the immediate challenge of Turkey’s assertive behavior in the Eastern Mediterranean, but also the future of EU-Turkey relations along with the pressing migration challenge. An updated EU-Turkey Statement should rectify certain provisions of the current Statement on migration regarding Greece as well as Turkey’s intention to exploit migrants and refugees. Greece is in favor of a “rules-based” relationship between the European Union and Turkey. It could be an active contributor to the advancement of the EU strategy of “balancing engagement” by co-shaping Turkey’s new relationship with the EU.

You may read the Policy Paper by Panayotis Tsakonas, Senior Research Fellow, Head, Security Programme, ELIAMEP; Professor of International Relations, Security Studies & Foreign Policy Analysis, University of Athens, in pdf here.

INTRODUCTION

This policy paper addresses two interconnected issues of particular importance to the EU, namely the future of EU-Turkey relations and the better management of the migration and refugee challenge, in which Turkey plays a pivotal role.[1]

“Especially with regard to EU relations with Turkey, Borrell did not hesitate to stress that “they have reached a critical junction” and “they are at a watershed moment in history”.”

At the end of July 2020, the attention of the EU and Germany, which has held the EU Council Presidency since July 2020, shifted towards the crisis that erupted in the Eastern Mediterranean after Turkey’s decision to deploy a research vessel, escorted by several warships, in non-delimited maritime zones claimed by Greece. Unfortunately, this was only the latest display of the assertive foreign policy followed by Turkey, especially since the failed military coup in 2016, featuring military interventions and challenges to the legal order in the Eastern Mediterranean. In mid-September, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Josep Borrell, referred to this harsh reality the EU is facing, namely the assertive come-back of the “old empires” – i.e. Russia, China and Turkey – vis-a-vis their immediate neighborhood as well as globally. Especially with regard to EU relations with Turkey, Borrell did not hesitate to stress that “they have reached a critical junction” and “they are at a watershed moment in history.”[2]

“Provided constructive efforts to stop illegal activities vis-à-vis Greece and Cyprus are sustained, the European Council has agreed to launch a positive political EU-Turkey agenda.”

Prior to the EU Council meeting on 1-2 October, where the future of EU-Turkey relations was to be discussed, a de-escalation of the longstanding crisis in the Eastern Mediterranean took place, with Turkey and Greece agreeing to move forward through the revitalization of “exploratory talks” and the launch of a confidence-building enterprise. At the European Council, member states welcomed the aforementioned positive developments, but at the same time they strongly condemned the violations of the sovereign rights of the Republic of Cyprus and called on Turkey to accept the invitation by Cyprus to engage in dialogue. Provided constructive efforts to stop illegal activities vis-à-vis Greece and Cyprus are sustained, the European Council has agreed to launch a positive political EU-Turkey agenda. Further decisions with regard to the situation in the Eastern Mediterranean are to be considered and taken by the EU as appropriate at its meeting in December 2020.[3]

At the time of writing of this policy paper (end of October 2020) the crisis in the Eastern Mediterranean has again escalated after Turkey’s decision to extend the seismic survey work of the research vessel Oruc Reis in a disputed area of the eastern Mediterranean until the beginning of November 2020. Greece condemned the extension of the survey as an “illegal move” which was essentially moving even further away from the prospect of a constructive dialogue, was at odds with efforts to ease tensions[4] and, most importantly, with the Conclusions of the EU Council of 16 October 2020. Indeed, the latter had not only reaffirmed its 1-2 October 2020 conclusions, but also deplored renewed unilateral and provocative actions by Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean. Apart from reiterating its full solidarity with Greece and Cyprus, the EU Council also urged Turkey to reverse these actions and work to ease tensions in a consistent and sustained manner.[5]

“…the EU should be the instigator of this comprehensive strategy, with the aim of altering Turkey’s calculus in the direction of constructive behavior vis-a-vis the EU.”

Accordingly, the EU has been called upon to develop a strategy that offers productive ways to address both the migration/refugee challenge and the future of EU-Turkey relations, while contributing to the stability of the Eastern Mediterranean. To this end, this policy paper argues that, in the coming months, the EU should be the instigator of this comprehensive strategy, with the aim of altering Turkey’s calculus in the direction of constructive behavior vis-a-vis the EU. Thus, Germany should work with France towards advancing a strategy of “balancing engagement” on Turkey. Such a strategy should aim to deter Turkey’s assertiveness (the French approach to containing Turkey), while preserving the anticipation of mutual benefits inherent in a policy of engagement (the German approach).

“Such a strategy should aim to deter Turkey’s assertiveness (the French approach to containing Turkey), while preserving the anticipation of mutual benefits inherent in a policy of engagement (the German approach).”

The first part of the policy paper discusses the current state of play and the obstacles the EU needs to overcome regarding EU-Turkey relations and the migration challenge. Specifically, with respect to the future of EU-Turkey relations, the paper examines the conditions that need to be fulfilled and the rationale that should be adopted by the EU to revitalize the bilateral relationship, using as its main vehicle the potential upgrade of the EU-Turkey Customs Union. To this end, the views of two key EU member states, namely Germany and Greece, regarding such revitalization of relations and a possible updated EU-Turkey Statement are also discussed. Indeed, both countries are key states when it comes to EU-Turkey relations. Germany is the EU country with the strongest trade relations with Turkey, while the large Turkish diaspora in Germany weighs in on both Turkish and German domestic politics. Greece has longstanding diplomatic disputes with Turkey over the Aegean Sea and Cyprus.

As far as managing the migration/refugee challenge is concerned, the paper provides an assessment of the current state of play. It focuses in particular on the weaknesses of the current EU-Turkey Statement on migration and its side-effects on the interests of its stakeholders, especially in view of the new deal that could be concluded between the EU and Turkey during the German EU Council Presidency. The second part of the paper discusses the rationale of the “balancing engagement” strategy the EU should pursue towards Turkey. Moreover, certain policy recommendations related to the essential elements of this strategy are also discussed, namely the future of EU-Turkey relations, dealing with Turkey’s destabilizing behavior in the Eastern Mediterranean, and the migration/refugee challenge.

STATE OF PLAY AND THE OBSTACLES TO OVERCOME

- EU-Turkey Relations

“Relations between the EU and Turkey became even more strained in the aftermath of the failed coup in July 2016 (with thousands of people arrested in Turkey without proper judicial process, the media being suppressed, etc.), raising serious concerns in most EU countries regarding respect for human rights and the rule of law.”

With a Customs Union agreement between the EU and Turkey entering into force in 1995, Turkey was officially designated as an EU candidate country at the EU Summit in Helsinki in December 1999, and official negotiations started in 2005. Since then, progress has been very slow (with 16 out of the 35 chapters opened and only one being closed to date). Relations between the EU and Turkey became even more strained in the aftermath of the failed coup in July 2016 (with thousands of people arrested in Turkey without proper judicial process, the media being suppressed, etc.), raising serious concerns in most EU countries regarding respect for human rights and the rule of law.

“Yet, stalling the membership process, blocking negotiations on the Customs Union and cancelling high-level dialogue did not prove to be a productive EU approach to preventing Turkey’s further democratic backsliding in terms of human rights, the rule of law and the militarization of its policies vis-a-vis two EU members in the Eastern Mediterranean, namely Greece and Cyprus.”

The EU-Turkey relationship is based on three pillars, namely the Association Agreement/Customs Union, the EU-Turkey Negotiating Framework of October 2005 and the EU-Turkey Statement of March 2016. In accordance with the conclusions of the General Affairs Council on 26 June 2018, the EU has predicated the opening of any new chapter in the membership process and the beginning of negotiations for the modernization of the Customs Union (CU) on Turkey’s steps towards democratization and improving the rule of law. Interestingly, this decision has changed after the conclusions of 1-2 October 2020, where the conditions for the commencement of modernisation talks with Turkey did not include democratisation and the rule of law. Yet, stalling the membership process, blocking negotiations on the Customs Union and cancelling high-level dialogue did not prove to be a productive EU approach to preventing Turkey’s further democratic backsliding in terms of human rights, the rule of law and the militarization of its policies vis-a-vis two EU members in the Eastern Mediterranean, namely Greece and Cyprus.

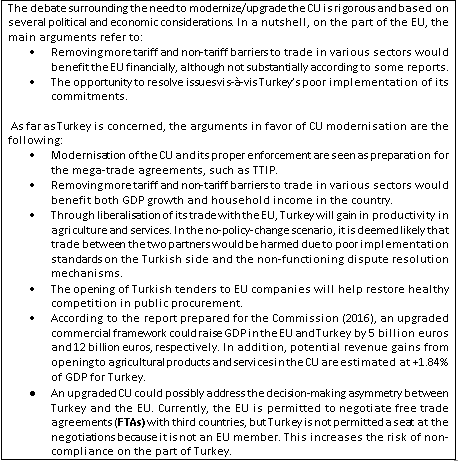

1.1. An upgraded Customs Union in lieu of accession?

“One may of course counter that Turkey is already on a slippery path, despite the EU’s best efforts, so the EU could instead wait for the “post-Erdogan era” to offer Turkey the CU modernization. This, however, could prove to be a long wait.”

While the accession process is de facto frozen, the EU has no good reason to suspend Turkey’s membership prospects formally. What is needed for a better and more functional EU-Turkey relationship is for the EU to update what needs to be updated, focusing mainly on trade and migration. In the matter of trade, the modernization of the Customs Union should not be seen as a gift to Turkey, but instead as a win-win situation that will bring economic benefits to the EU and its member states. From a political point of view, the EU member states have currently opted for an approach that “frontloads” conditionality for the trade negotiations to begin, instead of using the negotiations themselves as leverage to promote changes in Turkish behavior, with regard to its human rights record and good neighborly relations, and to reduce trade irritants in the current Customs Union. With Turkey not having much to lose, this will most probably prove to be a slippery path. One may of course counter that Turkey is already on a slippery path, despite the EU’s best efforts, so the EU could instead wait for the “post-Erdogan era” to offer Turkey the CU modernization. This, however, could prove to be a long wait.

1.2. What kind of conditionality?

“…any economic potential for Greece arising from a modernised Customs Union – even if Greece experiences a severe economic downturn due to Covid-19 – would not sugar the pill of serious security concerns deriving from non-constructive behaviour on the part of Turkey vis-à-vis migration issues and the Eastern Mediterranean.”

On the same line of reasoning, some analysts argue that the EU should not necessarily position the discussion outside the context of the EU accession negotiations, but deal with it as a trade agreement that needs to be negotiated with a very important partner, within the framework of the Association Agreement pillar of the relationship. Given the current environment of escalating tensions between Greece and Turkey, Greece would be unlikely to support the commencement of negotiations for an upgraded/modernized Customs Union as a means for coming to terms with the “New Turkey”; all the more so given that an upgraded Customs Union does not offer any political or security guarantees to Greece in case relations with Turkey deteriorate further. Therefore, any economic potential for Greece arising from a modernised Customs Union – even if Greece experiences a severe economic downturn due to Covid-19 – would not sugar the pill of serious security concerns deriving from non-constructive behaviour on the part of Turkey vis-à-vis migration issues and the Eastern Mediterranean.

“…according to the Greek government, the ruling New Democracy party and Greece’s major opposition party (SYRIZA), for Greece to accept the launch of negotiations for the upgrade/modernisation of the Customs Union and to further anchor Turkey in the EU, there are essential preconditions.”

Therefore, according to the Greek government, the ruling New Democracy party and Greece’s major opposition party (SYRIZA), for Greece to accept the launch of negotiations for the upgrade/modernisation of the Customs Union and to further anchor Turkey in the EU, there are essential preconditions. These include easing political tensions with Turkey and Turkey’s ceasing its aggressive and illegal behavior towards Greece in the Aegean and in the EEZs of Cyprus and Greece.[6] More importantly, in accordance with the EU Council Conclusions of 1-2 October 2020, the cessation of Turkey’s unilateral and illegal activities in the Eastern Mediterranean has also become a “European prerequisite” for any kind of substantive negotiations between the EU and Turkey to resume. With the above preconditions first fulfilled, the governing party (ND) along with the parties of the major (SYRIZA) and the minor (KINAL/Movement for Change) opposition appear receptive to sounding out the possibility of an upgraded Customs Union, provided that certain political conditions are also attached to it. To this end, Greece would accept the commencement of negotiations between the EU and Turkey towards a “Customs Union Modernization Plus,” with the incorporation of certain issues of particular importance to Greece, most notably related to security, defence and migration. Needless to say, Greece would also be in favour of the introduction of any kind of conditionality that would tie economic cooperation between the EU and Turkey to the fulfillment of certain conditions regarding human rights, democracy and respect for the rule of law.

“As Greece sees it, the EU must make it clear to Turkey that it cannot behave illegally towards an EU member state and towards the Union itself. At the same time, the EU cannot reward Turkey by tolerating violations of the Customs Union.”

Based on the fact that the continuation of Turkey’s illegal activities in the Eastern Mediterranean has failed to meet the prerequisites set by the EU Council conclusions of 1-2 October for the launch of the modernisation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union, Greece and Cyprus decided in late October to call off the meeting of the EU-Turkey joint committee that was to discuss the existing EU-Turkey Customs Union.[7] Moreover, Greece has decided to ask the European Union to examine the possibility of fully suspending the Customs Union with Turkey, as a clear message of disapproval of Turkey’s repeated illegal conduct. Specifically, in a letter sent to the European Commissioner for enlargement, Oliver Varhelyi, by the Greek Foreign Minister, Nikos Dendias, on 20 October 2020, Athens stressed that Ankara continues to unilaterally violate the EU-Turkey customs union by adopting tariffs and legislative and equivalent measures not foreseen under the agreement. Greece has thus asked the European Commission to consider the issue and propose immediate measures to stop this abusive practice. As Greece sees it, the EU must make it clear to Turkey that it cannot behave illegally towards an EU member state and towards the Union itself. At the same time, the EU cannot reward Turkey by tolerating violations of the Customs Union.[8]

Furthermore, stepping up his diplomatic efforts to mobilize European Union partners against Turkey, Greece’s Foreign Minister, in a letter to his counterparts from Germany, Spain and Italy, called on the three countries – and particularly Germany – to halt exports of military equipment to Turkey, including submarines and frigates. In a separate letter to EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs Josep Borrell, Dendias appealed for solidarity in line with the bloc’s mutual defense clause, which commits members to provide assistance “by all means” if another member is a victim of armed aggression. In the letter, Greece’s Foreign Minister stressed that the EU’s “benevolent approach to divergences” with Turkey, focused on dialogue, has been “to no avail.”[9]

- The Migration Challenge and the EU-Turkey Statement

The issue of migration has strengthened the nationalist trend in many European countries, boosting support for populist and Eurosceptic parties. The subsequent rise of xenophobia has hampered the development of robust collective instruments and a comprehensive migration strategy on the part of the EU. Indeed, the lack of a clear, common EU policy remains the biggest obstacle to a long-term solution to the migration challenge in Europe. Five years after the dynamic emergence of the migration/refugee challenge, the EU is still struggling to find its pace, and is still divided over the issues of burden-sharing and solidarity. The “New Pact on Migration,”[10]proposed by the EU Commission on 23 September 2020 for discussion by the member states, aims at tackling what is rightly considered “the elephant in the room,” namely the issue of lack of solidarity.[11] The 2015 migration crisis was a solidarity crisis and a big shock for the EU. Covid-19 has already had a dire economic, political, and social impact on the EU, including on migration, with the suspension of Schengen and the border restrictions/controls instituted by the member states. This may be making the discussion over refugee movements even more difficult, strengthening smuggling networks and raising both the risks and the costs of migrant and refugee movement.

“The subsequent rise of xenophobia has hampered the development of robust collective instruments and a comprehensive migration strategy on the part of the EU.”

Before the refugee surge of 2015, the EU already had a short-term interest in either deterring or preventing migrants from reaching the EU. If deterrence or prevention were to fail, the EU had an interest in better controlling irregular migration by using primarily restrictive tools, such as border controls, visa policy and the facilitation of return of irregular migrants either through agreements with key transit countries, i.e. Turkey, or through readmission agreements signed between the EU and Third Countries (countries of origin of migrants), as well as bilaterally between EU member states and certain Third Countries. The EU has also attempted to externalize border controls towards the Mediterranean countries by transforming them into a “buffer zone” to reduce migratory pressures. By keeping to the same “externalization” path, solutions with its partners were sought mainly through a deal with Turkey.

The EU-Turkey Statement, concluded on 18 March 2016,[12] is considered an important factor that led to a drop in arrivals to Greek shores. Yet the EU-Turkey Statement has not had the expected outcome. Indeed, it was due to the EU-Turkey Statement that migrants and refugees were forced to either use more dangerous routes (such as the central Mediterranean towards Italy) or remain trapped/stranded in Turkey. It also showed that prevention policies and the outsourcing of migration management strengthens transit countries such as Turkey,[13] without resulting in a steady reduction in flows. The crisis that erupted on the Greek-Turkish borders in Evros in early March 2020 is a case in point, as it brought the migration issue back to the forefront – and particularly Turkey’s role in its exploitation.[14] The implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement has also resulted in delays in both asylum processing and returns to Turkey, as well as in sub-standard conditions for those stranded on the Greek islands. More importantly, the Statement revealed a multitude of problems regarding the asylum system in the EU and the level of willingness of member states to “share” the burden and responsibility, with the latter falling directly on Greece, an already overburdened member state lacking the capacity to handle the situation.[15]

2.1. How can the stakeholders’ (Turkey and European states) views converge?

Migration is an issue in the broader bargaining game between the EU and Turkey. Unfortunately, Turkey’s erratic behavior (e.g. the exploitation of migrants and refugees as political leverage in late February/early March 2020 on the Greek-Turkish borders at the Evros river) projected it as an unreliable partner on migration, which does not help member states’ views converge on the matter of a possible update of the EU-Turkey Statement. Moreover, when it comes to migration there is an important caveat to keep in mind, namely that Turkey does not want to be used as a roadblock to migratory flows. Turkey would instead like to see more financial support given to refugees in Turkey, which could be used for the benefit of Syrian and non-Syrian refugees alike.

“Turkey would like enhanced EU support for migration management efforts on its Eastern borders, as well as political and financial support for its policy in Syria.”

Furthermore, Turkey would like enhanced EU support for migration management efforts on its Eastern borders, as well as political and financial support for its policy in Syria. Financial support in Syria could take the form of aid for Internally Displaced Persons in the Idlib area, or could be channeled to reconstruction projects in the Turkish controlled areas, with the goal of creating the right conditions for Syrian refugees in Turkey to return. This is a challenging demand from the Turkish side, because it is essentially asking the EU to fund an attempt to change the ethnic composition of the occupied territories in Northern Syria through the transfer of Syrian Arab refugees residing in Turkey into Syrian Kurdish areas that are occupied by the Turkish army at the moment.

The EU is thus called upon to develop a contingency plan that convincingly presents how far it can go in outsourcing either its foreign policy in Syria and Libya or its migration policy to Turkey. The EU should also be cautious in joining forces with Turkey in the minefield of the Middle East, where there is very limited convergence of EU and Turkish strategic interests (quite different approaches on Syria, with Turkey belonging to one of the two opposing camps in the Middle East). However, when a common approach is found, the EU may work together with Turkey to the benefit of both parties.

To build a “win-win relationship” the EU migration policy needs to be comprehensive and holistic. To this end, the EU should find a way to become relevant again for member states by building a common win-win EU approach and proving its added value. The member states should empower the Union politically and practically. The role of Germany in the process of empowering the Union and in putting the long-term common good before short-term national interests, and thus leading by example, is vital. This is of particular importance in view of a new deal that needs to be concluded between the EU and Turkey, with the German EU Presidency laying the groundwork for further work and consultations.

THE WAY AHEAD

- Devising a European Strategy of “Balancing Engagement” on Turkey

It is clear that a reset of the EU-Turkey relationship is now needed more than ever. The EU realizes that Turkey is both the cause of and part of the solution to the problem of regional and European stability and security. It must not be forgotten that any effective strategy the EU may devise for dealing with Turkey should embrace the right mix of sticks and carrots and the right balance of benefits and obligations for Turkey. Moreover, a European strategy towards Turkey should address not only the immediate challenge of Turkey’s assertive behavior in the Eastern Mediterranean, but also the future of EU relations with Turkey along with the pressing migration challenge. To this end, the most effective strategy the EU can devise is an updated arrangement between the EU and Turkey.

“The EU realizes that Turkey is both the cause of and part of the solution to the problem of regional and European stability and security.”

Is the EU in the position to accomplish such a demanding task? The good news is that the Covid-19 pandemic has awakened the EU from economic and political slumber. Moreover, thanks to the leading role played by the French-German partnership, a groundbreaking budget agreement was adopted by the European Council on 21 July 2020. The agreement on the recovery package has arguably given the most important boost to EU integration since the launch of the euro, allowing the EU to emerge from the pandemic crisis stronger and more unified. The EU’s geopolitical awakening[16] is mostly related to its realization that it should further advance its “strategic autonomy” in order to defend its sovereignty and promote its interests independently from the United States. Specifically, Germany and France should use the momentum they created through their agreement on the Recovery Fund and act together to give the EU a stronger geopolitical voice.[17] Acting together, France and Germany can combine ambition and pragmatism to “put some flesh on the bones” of the geopolitical awakening of the EU and its subsequent foreign and security policy. Germany and France should be the essential drivers of an EU strategy of “balancing engagement” on Turkey. This strategy aims at preserving the hope inherent in the engagement policy for Turkey, while deterring Turkey’s assertiveness.

3.1. The differing, yet complementary, approaches of France and Germany

Can the differing approaches adopted – and the policies followed – so far towards Turkey by the two leading European states be viewed as complementary? For President Macron, Turkey’s provocative and assertive behavior in the Eastern Mediterranean, along with the migration/refugee crisis, has made European borders more relevant than ever. For France, the European Union, without the protective U.S. umbrella, should start speaking “the language of power, without losing sight of the grammar of cooperation.”[18] France is also determined to remain a power in the Middle East, North Africa, and the Eastern Mediterranean, and to exercise power to bring order and stability to the region (Pax Mediterranea), preventing Turkey from shaping the region in its favor.[19] Moreover, France has not hesitated to support Greece, mobilizing its naval fleet in the Eastern Mediterranean and tightening bilateral ties, playing a leading role in having all European MED7 countries strongly criticize Turkey’s provocative and illegal behavior,[20] and pushing for targeted sanctions against Turkey and for the replacement of the current accession negotiations scheme with another EU-Turkey partnership that would concern the economy, energy, migration, and culture.

Chancellor Merkel is instead more interested in following a policy of “strategic patience” vis-a-vis Turkey and not letting Turkey move further away from the EU or become a “lone wolf.” Germany is in favor of Turkey’s engagement with the EU, arguing that, although Turkey’s accession process is de facto frozen, the EU has no good reason to suspend Turkey’s membership prospects formally. Moreover, the start of negotiations for the modernization of the EU-Turkey Customs Union would constitute leverage to achieve changes to Turkish behavior with regard to its human rights record and good neighborly relations.

Fortunately, the meeting between President Macron and Chancellor Merkel on 20 August 2020 at the Fort de Brégançon was a clear indication that the policies of the two leading European states could be viewed as complementary. Indeed, although Macron and Merkel have employed different (military vs. diplomatic) means in dealing with Turkey and the current crisis in the Eastern Mediterranean, they also agreed that they have a shared agenda for the region and that they are determined to work together to ensure stability while favouring de-escalation.

“…a European strategy on Turkey that includes both “sticks and carrots” was agreed and adopted by the EU heads of state in the European Council on 1 October 2020.”

Going even further, a European strategy on Turkey that includes both “sticks and carrots” was agreed and adopted by the EU heads of state in the European Council on 1 October 2020. On the one hand, the EU has decided that, in case of renewed Turkish unilateral actions or provocations in breach of international law, “the EU will use all the instruments and the options at its disposal, including in accordance with Article 29 TEU and article 215 TFEU, in order to defend its interests and those of its Member States.”[21] At the same time, and provided that Turkey’s constructive efforts to stop illegal activities vis-à-vis Greece and Cyprus are sustained, the EU has also decided to embark upon developing a proposal for re-energising the EU-Turkey agenda. Specifically, the EU members have agreed “to launch a positive political EU-Turkey agenda with a specific emphasis on the modernisation of the Customs Union and trade facilitation, people to people contacts, High level dialogues, and continued cooperation on migration issues, in line with the 2016 EU-Turkey Statement.”[22]

3.2. In search of the right balance between “sticks and carrots”

By referring to the EU’s strategy for dealing with Turkey as one of “sticks and carrots,” the President of the EU Council, Charles Michel, also shares – along with other top officials in the EU, such as the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell, – the rationale of the EU’s “balancing engagement” strategy. Indeed, the EU approach should represent a balanced position that protects its interests while remaining open to dialogue and cooperation. This dual-track approach suggests that the EU and its member states must be united and firm on issues where their interests are at stake, but also on the need to get Turkey to engage constructively. Apparently, the EU is still in search of identifying the particular tools it should use to improve its relations with Turkey while making it clear to Turkey that the EU should be respected. It should be noted, however, that Turkey seems to be completely indifferent – as if the framework of the 1-2 October 2020 EU Council conclusions is non-existent – to the policy of “sticks and carrots” introduced and pursued by the EU. Yet, a European Plan B, in case Turkey continues on the path of hard confrontation, is still missing.

“The aim of the EU strategy of “balancing engagement” – or a “sticks and carrots” approach – when it comes to Turkey is to devise a package that could alter Turkey’s strategic calculus, leading it to pursue constructive behavior towards the EU.”

The aim of the EU strategy of “balancing engagement” – or a “sticks and carrots” approach – when it comes to Turkey is to devise a package that could alter Turkey’s strategic calculus, leading it to pursue constructive behavior towards the EU. In the post-pandemic era, it is most likely that pressure will increase on both Turkey and the EU member states. The EU should thus make use of and build upon Erdogan’s current and future needs. Turkey is in need of status and recognition for being a regional power, a “central state,” with a role in European and regional politics. The question of status cannot be eschewed. Moreover, Erdogan believes in personal politics and opts for deals with leaders on a personal basis.

Unfortunately, President Erdogan persists in behaving provocatively not just towards Greece and Cyprus, but also towards France – and President Macron personally – and the EU. By the end of October 2020, and after months of rising tensions between France and Turkey, Erdogan first attacked President Macron, questioning his mental health for speaking out so forcefully against Islam, later calling for a boycott of French goods. European leaders have come out in support of France, expressing their “full solidarity” with President Macron and stressing that personal insults “do not help the positive agenda that the EU wants to pursue with Turkey“[24] (our emphasis). Indeed, EU-Turkey relations still appear to be in tatters, mainly because Erdogan’s choices in terms of governance are the exact opposite of EU norms and standards,[25] while he also expresses a revisionist logic without drawing on international law.

“Regardless of how long Erdogan sticks to a provocative mind-set and to counter-productive choices, the European Union should remain firm in devising a strategy to deal with Turkey’s behavior as being both the cause of and the solution to the problem.”

Regardless of how long Erdogan sticks to a provocative mind-set and to counter-productive choices, the European Union should remain firm in devising a strategy to deal with Turkey’s behavior as being both the cause of and the solution to the problem. Turkey is indeed a necessary partner of the EU on energy and security issues, as well as on the management of the migration challenge. A productive relationship between the EU and Turkey should therefore be one based on rules as well as on interests.

In building a new relationship between the European Union and Turkey, the right balance between sticks and carrots is of critical importance. With reference to the EU Council Conclusions of 1-2 October 2020, it seems that, although there is a lack of unity among EU member states on the future of Turkey in Europe, there is consensus on the need for a common EU foreign and security policy on Turkey. This agreement among EU member states suggests that the process of EU membership has been set aside for the moment and is separated from the EU-Turkey Customs Union. The utility and effectiveness of sanctions is also an issue that needs careful consideration. Indeed, EU sanctions against Turkey, especially well elaborated and targeted sectoral sanctions, would – if agreed and implemented –definitely send a clear and meaningful message to Turkey to change course from its assertive and provocative behaviour. However, to deal with Turkey effectively, a European policy of sanctions[26] should be complemented with initiatives that need to be perceived by Ankara as being of substance and credibility.

“A European strategy of “balancing engagement” should thus address three particular issues, the most urgent one being Turkey’s destabilizing behavior in the Eastern Mediterranean, together with the modernization of the EU-Turkey Customs Union and the update of the EU-Turkey Statement.”

A European strategy of “balancing engagement” should thus address three particular issues, the most urgent one being Turkey’s destabilizing behavior in the Eastern Mediterranean, together with the modernization of the EU-Turkey Customs Union and the update of the EU-Turkey Statement. Interestingly, the EU Council of 1-2 October 2020 made it clear to Turkey that, for a positive political EU-Turkey agenda to be launched – and thus for the modernization of the EU Customs Union to proceed – Turkey must first make constructive efforts to stop illegal activities vis-à-vis Greece and Cyprus. Moreover, by recalling and reaffirming its previous, October 2019 conclusions on Turkey, the EU has also made clear to Turkey that, in case of renewed unilateral actions or provocations in breach of international law, the EU will impose severe economic sanctions on Turkey.

“…we should keep in mind that the EU-Turkey Statement is not just about migration. Turkey is expected to seek the recommitment of the EU to issues beyond migration and trade/economy, e.g. visa liberalization, accession negotiations/chapters, Syria.”

The EU should embark upon a new EU-Turkey understanding that consists of two pillars: trade and economic considerations, for the purpose of updating the EU-Turkey Customs Union, and migration, for the purpose of re-negotiating the 2016 EU-Turkey Statement. It is worth noting that Turkey is very much interested in a “re-start” in its relations with the EU, through an agreement that would not only promote the revitalization of the existing EU-Turkey Statement, but also include other forms of cooperation, such as the modernization of the EU-Turkey Customs Union or the issue of visa liberalization.[27] However, we should keep in mind that the EU-Turkey Statement is not just about migration. Turkey is expected to seek the recommitment of the EU to issues beyond migration and trade/economy, e.g. visa liberalization, accession negotiations/chapters, Syria.

3.2.1. Modernization of the EU-Turkey Customs Union

“The Customs Union is an important instrument and the only leverage at the EU’s disposal for concluding an agreement with Turkey.”

The Customs Union is an important instrument and the only leverage at the EU’s disposal for concluding an agreement with Turkey. As noted, the EU should not necessarily put the discussions outside the context of the EU accession negotiations, but deal with it as an agreement that needs to be negotiated with a very important partner. Negotiations can indeed lead to an agreement that would balance the European and Turkish interests. Yet, for EU-Turkey negotiations on the modernization of the Customs Union to begin, Greek and Cypriot concerns about Turkey’s aggressive and illegal behavior in the Aegean and in Cyprus and Greece’s Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) need to be taken into account.

It should also be considered that the modernization of the Customs Union has been frozen since June 2018, well before the beginning of Turkey’s drilling in the EEZ of Cyprus. That was due to Turkey’s human rights record, as well as the fact that Turkey is not implementing the current Customs Union towards Cyprus. By implication, there might be certain member states not fully agreeing to negotiations for a modernized Customs Union, even if the environment in the Eastern Mediterranean becomes more favorable.

3.2.2. Update of the EU-Turkey Statement on migration

“Updated arrangements on migration between the EU and Turkey (through the re-negotiation of the existing EU-Turkey Statement) remain at the top of the list of policies the EU is called upon to adopt.”

Modernization of the Customs Union needs to be linked to an updated EU-Turkey Statement on the thorny issue of migration. Updated arrangements on migration between the EU and Turkey (through the re-negotiation of the existing EU-Turkey Statement) remain at the top of the list of policies the EU is called upon to adopt.

EU Commission VP Margaritis Schinas highlighted the importance of Turkey when he described relations between the EU and Third Countries of origin, and especially key transit states (the external dimension) as being the first floor of the proposed New Pact on Migration and Asylum or the basis of a “three-story building.”[28] The second pillar in his metaphor is the robust common management of the EU’s external border, while the third is solidarity, implying that for the third and the second floors to be solid, the first one (a new deal with Turkey) needs to be solid.

An updated EU-Turkey Statement should rectify certain provisions of the EU-Turkey Statement on migration regarding Greece. These are the readmission to Turkey of migrants crossing to the EU through the land borders, the possibility of transfers from the Greek islands to the Greek mainland (without losing the right of readmission to Turkey) and the inclusion of explicit provisions in the Statement for returns to take place via regular and charter flights from airports on the mainland, so long as the returnee’s initial registration took place on the islands.

Given that cooperation between the EU and Turkey is still considered a conditio sine qua non for managing the migration challenge, an updated, more effective EU-Turkey Statement should address the current deficits (described in the previous section) of the existing framework as well as Turkey’s intention to exploit migrants and refugees. Following the 9 March 2020 meeting of the EU leadership with President Erdogan, High Representative and Vice President Josep Borrell met with Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu to identify areas in which the implementation of the EU-Turkey Statement could be improved.

It should also be stressed that a renegotiation of the current EU-Turkey Statement on migration should promote the integration of Syrian refugees and provide access to protection for non-Syrian refugees, as many would prefer to stay in Turkey if opportunities existed. However, the socio-economic situation in Turkey is currently deteriorating, impeding potential integration, especially in the urban centers.

An attempt should also be made to reduce Turkey’s exploitation of refugees to gain political leverage, through an updated EU-Turkey Statement. This could be achieved by focusing on increasing the number of returns directly to countries of origin, to an extent bypassing Turkey as a transit country, and by creating direct legal avenues of entry to the EU. This will again mean that Turkey (and similar transit countries) will have reduced leverage, since people will be able to reach the EU directly. This is obviously easier said than done, given that Turkey is likely to remain a transit country even if failed asylum seekers are returned directly to their countries of origin from the EU. Furthermore, part of the logic of the EU-Turkey Statement is to let Turkey handle returns, since it appears to be more successful at them than the Greek authorities (or most other EU member states for that matter). This is partly because Turkey has better diplomatic relations than many EU states with many countries of origin in Africa and the Middle East.

It goes without saying that the EU should guarantee adequate, if not generous, financial support for Turkey, which is hosting the largest population of refugees in the world, and provide funding of the same magnitude as that promised in the 2016 EU-Turkey agreement. Accordingly, after the Commission proposed this, the European Parliament agreed in its July 2020 Plenary to boost humanitarian aid to refugees in Turkey by 485 million euros. This support may be provided to Turkey through the Multiannual Financial Framework (2021-27), perhaps linked with a suspension clause in case Turkey decides to exploit migrants and refugees again. Last but not least, the way any new deal between the EU and Turkey is communicated to the citizens of the European member states and Turkey is also of particular importance.

“Greece could be an active contributor to the advancement of the EU strategy of “balancing engagement” by co-shaping Turkey’s new relationship with the EU.”

Clearly, EU-Turkey relations will remain relevant in the years to come in many fields, most importantly in economics and security. Although disruption remains the norm in Turkey’s behavior, the EU should stand firm in developing a strategy of “balancing engagement” to keep Turkey anchored in the broader European and transatlantic framework. Obviously, Greece is also in favor of a “rules-based” relationship between the European Union and Turkey that functions in accordance with international law and results in good neighbourly relations. Moreover, Greece could be an active contributor to the advancement of the EU strategy of “balancing engagement” by co-shaping Turkey’s new relationship with the EU. To this end, Greece could impart “positive aspects” to the Greek-Turkish bilateral agenda by choosing to highlight the prospects for bilateral cooperation on issues of common interest, such as Covid-19, organized crime, climate change, etc.

[1] This policy paper has benefited from an online brainstorming meeting of foreign policy experts and practitioners convened on 24 April 2020 by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung Athens and ELIAMEP, where EU-Turkey relations and the migration/refugee challenge were discussed under Chatham House rules. Most of the views and recommendations provided by the participants of the meeting have been incorporated into this policy paper.

[2] “Role of Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean”, Remarks by the High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell at the European Parliament plenary, Brussels, 15 September 2020 (Available at:

https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage_en/85128/

Role%20of%20Turkey%20in%20the%20Eastern%20Mediterranean:%20Remarks%20by%20the%20High%20Representative%20/%20Vice-President%20Josep%20Borrell%20at%20the%20EP%20plenary.

[3] EU Council Conclusions, 1-2 October 2020, Brussels 2 October 2020 (EUCO 13/20, CO EUR 10) (Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/10/02/european-council-conclusions-1-2-october-2020).

[4] Selcan Hacaoglu, “Turkey-Greece Feud Escalates After They Cancel War Games”, 26 October 2020. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-10-26/turkey-greece-feud-escalates-after-they-cancel-war-games?sref=bGmT7ML1.

[5] EU Council Conclusions, 16 October 2020, Brussels 16 October 2020 (EUCO 15/20, CO EUR 11 CONCL 7). Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/10/16/european-council-conclusions-15-16-october-2020).

[6] Panayotis Tsakonas & Athanassios Manis, “Modernizing the EU-Turkey Customs Union: The Greek Factor”, Policy Paper No. 35, Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP), July 2020. Available at: https://www.eliamep.gr/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Policy-paper-35-Tsakonas-Manis-06.07-final-1.pdf.

[7] Evie Andreou, “Greece wants EU to look at fully suspending Customs Union with Turkey”, Cyprus Mail, 20 October 2020. Available at: https://cyprus-mail.com/2020/10/20/greece-wants-eu-to-look-at-fully-suspending-customs-union-with-turkey.

[8] See the interview of the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Nikos Dendias, in ‘Realnews’, with journalist Giorgos Siadimas, 25 October 2020. Available at: https://www.mfa.gr/en/current-affairs/statements-speeches/interview-of-the-minister-of-foreign-affairs-nikos-dendias-in-realnews-with-journalist-giorgos-siadimas-25-october-2020.html.

[9] See “Greece Seeks Arms Embargo, Halt to EU-Turkey Customs Union”, 20 October 2020. Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-10-20/greece-seeks-arms-embargo-suspension-of-eu-turkey-customs-union.

[10] COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE COUNCIL, THE EUROPEAN ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMITTEE AND THE COMMITTEE OF THE REGIONS on a New Pact on Migration and Asylum, Brussels, 23.9.2020 COM (2020) 609 final. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/1_en_act_part1_v7_1.pdf.

[11] For an assessment of the pros and cons of the proposed “New Pact on Migration” see Sergio Carrera, “Whose Pact? The Cognitive Dimensions of the New EU Pact on Migration and Asylum”, CEPS Policy Insights, No2020-22, September 2020. Available at: https://www.ceps.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/PI2020-22-New-EU-Pact-on-Migration-and-Asylum.pdf.

[12] The agreement established: the return of migrants in an irregular situation to Turkey; the return to Turkey of people applying for asylum whose application for protection has been declared inadmissible prior to detention in the centres established for that purpose; for each person of Syrian nationality returned to Turkey under the assumption of being a safe country, one person applying for asylum in Turkey from Syria shall be resettled in Europe; the EU will provide €3 billion to Turkey to manage the refugees in the country. At no time does the agreement mention refugees of other nationalities. However, according to official sources consulted, the agreement is being applied extensively to people from other countries as regards returns to Turkey. See European Council: “EU Turkey Statement 18 March 2016”. Available at http://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18-eu-turkey-statement.

[13] Recent studies examining the foreign policy responses of three major refugee host states, namely Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, have found that Jordan and Lebanon deployed a back-scratching strategy based on bargains while Turkey deployed a blackmailing strategy based on threats. Interestingly, the choice of strategy depended on the size of the host state’s refugee community and domestic elites’ perception of their geostrategic importance vis-a-vis the target. See Gerasimos Tsourapas, Journal of Global Security Studies (Vol.4, Issue 4, October 2019), pp. 464–481, available at: https://academic.oup.com/jogss/article/4/4/464/5487959.

[14] Angeliki Dimitriadi, “Refugees at the Gate of Europe”, Policy Brief #112, Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP), 22 April 2020. Available at: https://www.eliamep.gr/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Policy-brief-Angeliki-Dimitriadi-final-1.pdf

[15] Angeliki Dimitriadi, “The Impact of the EU-Turkey Statement on Protection and Reception: The Case of Greece”, Working Paper No. 15, Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP); Instituto Affari Internationali (IAI); Stiftung Mercator; Istanbul Policy Center (IPC), October 2016, available at: http://www.iai.it/sites/default/files/gte_wp_15.pdf.

[16] Max Bergmann, “Europe’s Geopolitical Awakening. The Pandemic Rouses a Sleeping Giant”, Foreign Affairs, August 20, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/europe/2020-08-20/europes-geopolitical-awakening.

[17] Jana Puglierin and Ulrike Esther Franke, “The Big Engine that Might: How France and Germany Can Build a Geopolitical Europe”, Policy Brief (European Council on Foreign Relations, July 2020). Available at: https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/the_big_engine_that_might_how_france_and_germany_can_build_a_geopolitical_e.

[18] Clément Beaune, “Europe after COVID”, 14 September 2020 (the French minister of State for European affairs and former adviser to president Macron) article on the state of and perspectives for Europe after the pandemic crisis). The English translation of the text was published exclusively by the Atlantic Council’s Future Europe Initiative. Available at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/commentary/feature/europe-after-covid/

[19] Steven A. Cook, “Macron Wants to Be a Middle Eastern Superpower”, Foreign Policy, 15 September 2020. Available at: https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/09/15/macron-france-lebanon-turkey-middle-eastern-superpower.

[20] https://www.insideover.com/politics/conclusions-from-the-med7-meeting-in-corsica.html

[21] EU Council Conclusions, 1-2 October 2020, Brussels 2 October 2020 (EUCO 13/20, CO EUR 10)

[22] Ibid.

[23] European Union leaders decided to adopt a “sticks and carrots” approach at the EU Council meeting on 24-25 September 2020. According to the EU Council President, Charles Michel, “We will identify tools in our external policy, a sticks and carrots approach – what tools to use to improve the relationship and what tools to react (with) if we are not being respected”. However, Michel declined to discuss the specific incentives or punitive steps the EU could take with respect to Turkey. See Gabriela Baczynska, “EU to hone ’carrot and stick’ line on Turkey at summit – top official”, 15 September 2020, available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/eu-turkey-int-idUSKBN25V1OP.

[24] “Turkey’s Erdogan urges French goods boycott amid Islam row”, 26 September 2020. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-54692485

[25] Mark Pierini, “Turkey’s Labyrinthine Relationship with the West: Seeking the Way Forward”, Policy Paper #38, September 2020, p.9. Available at: https://www.eliamep.gr/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Policy-Paper-38-FINAL-11.09-1.pdf

[26] For some analysts, EU sanctions on Turkey would primarily hurt Turkey’s economy, yet they would also hurt European businesses. They might also prove counterproductive by making Turkish public opinion more nationalistic and anti-Western; leading Ankara to complicate NATO’s defense planning; and/or prompting retaliation on the part of the Turkey by pushing migrants towards Europe. See Luigi Scazzieri, “Can the EU and Turkey Avoid More Confrontation?”, Insight, Centre for European Reform, 10 August 2020. Available at: https://www.cer.eu/insights/can-eu-and-turkey-avoid-more-confrontation.

[27] Particular reference was made by President Erdogan’s closest foreign policy and security advisor, Ibrahim Kalin, during his visit to Berlin in mid-June 2020, to Germany for being the EU member state that can lead the way to the revitalization of the EU-Turkey relationship during its EU Presidency.

[28] Commission Vice President Margaritis Schinas’s interview with Florian Eder at Politico, 11 June 2020. Available at: https://www.politico.eu/newsletter/brussels-playbook/politico-brussels-playbook-brexit-looks-bad-migration-latest-you-read-it-here-first-label-the-euros/